![]()

9.5.14

When I left Thomas More Square last night it was almost midnight, a common departure time for a reporter or an Editor of The Times, less so for an Editor of the TLS. A searchlight was hanging in the sky, drawing circles on the ground, hung from a helicopter, I presumed, although behind the Level Six glass I could not hear it. A bright metallic pool of light made an ice-rink of the gatehouse car park for the old plant, the ground immediately below. Slowly the beam found the long, low line of brick behind, the dockland Rum Store that once housed The Times, suddenly gold instead of black.

Then the light hit the red cube built for the Sun and the News of the World, for the managers, the lawyers, the accountants, the print machines themselves, six stories high and newly spot-lit as though for a conjuror’s trick. Finally it traced a bright white line between The Old Rose on the Highway and the river before sweeping on again to the steeples and tower blocks beyond. A manhunt? A preparation for a visiting president?

This morning there is only hard, horizontal rain against the warehouse opposite the plant gates, low cloud propelled by wind around the large white letters, A, B and C, that are stencilled on the black-painted brick. This windowless break against the storm carries the name of Thomas Telford, a Victorian master of brick. The next wall celebrates a Mr Breezer. Neither of these names was visible last night, nor in 1986 even during the day. So much was obscured then.

There is also a deep pit down below me that was not there in 1986, not there yesterday either, newly dug by a yellow machine behind the gate, just inside the gate that last night was an ice-rink of light, where the battles of Wapping were fought and where the destruction of the main building will soon begin. The straight-cut sides of what will perhaps be a pond are some six-feet wide and twelve-feet long.

This was only one part of the battlefield, not a part of great significance at the time. The pit is simply in the part that I can now see from my window, something that I can show Miss R if she asks.

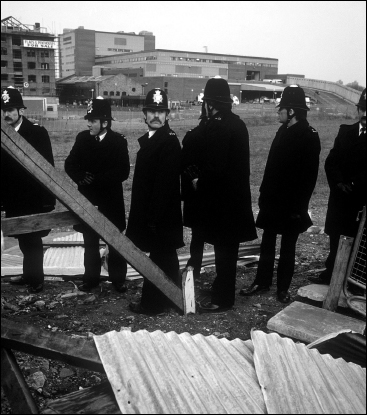

When the newspapers first arrived this was the eastern corner of the car park, though not a place where any sane man or woman would park a car. Wapping was a genuine battlefield, not a metaphorical one, not a football match. The only metaphors were the ones written by the journalists inside, the same tired phrases day after day as Frank Johnson complained. When the Socialist Workers came among the pickets, or when the police came among the International Marxists, this pit was where the missiles were thrown and thrown away.

So a battle with weapons? Yes. Bitter and brutal? Yes, sometimes it was both. The print union leaders knew that if newspapers could be made without their members at Wapping, their power would be over in Fleet Street and everywhere. And so it proved.

‘But how bitter and brutal?’ That is the first question from Miss R this morning who arrives with a copy of the Daily Mirror and the London Review of Books, both competitors from the Left to the papers of Thomas More Square. ‘Was it as bad as the battlers on both sides made out? Missiles? How many and how often? Weren’t you exaggerating as newspaper people do?’

‘Well, yes, probably more weapons were thrown away than thrown. That was what David Hart used to insist, always with sadness. David was a devout fighter in the Thatcher army. He wanted the battles to be as bitter and brutal as possible.’

‘Why? What did he want?’ She wrenches the subject from politics to people. I am coming to expect this now.

‘Where did David come from? Where did the rest of the court come from?’

‘Certainly not all from the same place.’ She makes a note.

‘I wondered often about David. I occasionally asked him. There was an official story – about a Jewish banker’s family, some trouble with a gardener’s daughter at Eton, a little film production, a larger bankruptcy, a life of property speculation, military procurement and the mind. And there was a story of a different kind of intelligence, Mossad and the CIA and even sometimes our own.’

‘When did you see him first?’ Miss R’s second question today is one of her stock questions.

‘In David’s case the time of seeing and meeting were, in fact, the same.’

‘When?’

‘It was a year before the night at the Greenwich Theatre. He had first written me a note while I was still at Shell and pushing stories through magazine doorways. He was curiously well informed. I should have seen the oddity in that. He found me when I barely knew where I was myself. He asked me to lunch and I accepted.’

‘What did he look like then?’ Miss R asks without waiting to hear any more.

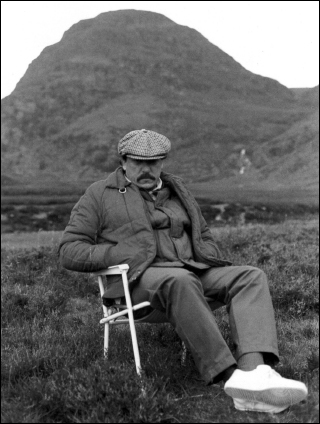

David Hart

‘Well, he had a head that I most certainly did not want to be hit by.’

She looks quizzically.

‘Yes, I know that this is a bad sentence; Frank advised against ending any sentence with a preposition; so did the late Richard Brain of the TLS and so does the style guide of The Times. But ‘hit by’, positioned for emphasis, purposefully out of its proper position in the way that Latin allows, suits a memory of David’s head very well.’

‘I first saw him as a reflection, an image in the wood of a dining room table, in a house where he could throw walnuts into the gardens of Buckingham Palace. I was late and he was already sitting with his back to a mahogany door, black hair cropped short, broad neck bound in a red napkin, talking to his butler, looking like some prosperous communist propagandist, the kind imagined by novelists when Marxism was in its youth.’

‘I sat down next to him (there were only two chairs) and he thrust his head towards me, the bristles on his brow almost on the bridge of my nose. He began with paintings by Walter Sickert, bought by his father, he said, who had beaten Lord Beaverbrook for them, none costing more than £200, one of them connected in some way to the Camden Town murder of 1907. He affected surprise that I had not heard of this great news event of its time, the throat-slitting of a prostitute, a Jack-the-Ripper story but from west not east.’

‘I nodded with minimum commitment. His Sickerts seemed a well trodden path of conversation, the first of many such paths as I came to discover. David liked best what was familiar to him but exotic to others. He moved on to D. H. Lawrence (perhaps he thought this would give a better impression) and about belief belonging to “the blood” not the “fribbling intervention of mind” (which merely made me think he was mad). Then came the subject of traitors and “tagging” and how, if he did not trace and track down the subversives in the political departments of the press – “not excluding The Times” – the chances of Margaret Thatcher coming to power were even less than conventional wisdom decreed.’

‘I smiled at him. I was merely a reader of The Times back then. Lunch for the two of us was a pyramid of roast birds and bright vegetables. It seemed impossible to me that a quail or an artichoke or quince could be removed without the structure’s collapse. But a shaven-headed boy filled our plates and nothing fell. David had a silver toothpick and a thin grey dog that he said was a lurcher.’

‘After this first time we remained friends till his death in January 2011. When I was powerful he was a pest. When he was a friend in need he was also a pest. But he was a very special pest and I was fond of him.’

‘He was physically strong, recognisably so in rooms where most were writers, well able to lift an enemy or a bale of hay until in the last decade of his life he was gradually wasted by disease and could barely lift an eyebrow.’

‘As a narrator of the truth he was frail, a fuzzy presenter of his own past even as he was a very precise observer of the present that we came to share. So I am sure that he was right about where the Wapping missiles went. Many of the throwers at that part of the line were clerical workers and journalists. There must be many a reminder in that pit of sharpened iron and glass, some of it hurled in anger, most discarded in fear.’

‘David pretended much of his knowledge but he did understand dissent. Unless it was his own he was against it. He made a speciality of finding Margaret Thatcher’s enemies. He came to know her through one of her favourite think tanks, the Centre for Policy Studies. He befriended its most radical members. He was resilient to failure, sending to her short speeches and thoughts for speeches, accepting that lesser, closer courtiers would keep them from her until from time to time he broke through.’

‘When I first wrote about politics this softly moustachioed Mr Hart was the most belligerent, bull-headed, most vehement, viscerally political man I had then met. I had not seen such raging certainty for twenty years.’

Miss R lowers her head towards her notes, murmuring a query without looking at me.

‘That first man of certainty was the right-wing Essex father of my left-wing Essex girlfriend or, to be strictly honest, the girl I most wanted to be my friend. He need not be part of your story. He and David, for all their shared frustrations with the world, could never possibly have met.’

She pushes her pen into her paper, pulls it back and points for me to go on.

‘David believed most of all in battling an enemy to the end’, I tell her, returning to the former field of conflict in front of our eyes.

‘Thus Wapping was something of a disappointment to him. Except on Saturday nights when the pickets’ enemies, police horses mostly, felt the force of ball-bearings and darts, this was a mostly peaceful show. No newspaper worker, he would wistfully complain, wanted to be caught with an object that might be interpreted as a Molotov cocktail. It was much safer to toss a Coke bottle over the low part of the car park wall, where the pit has now appeared, than to risk its association with someone else’s cottonbud fuses or four-star fuel’.

‘A Molotov, said David as though he had known the inventor personally, was much more appropriate as a talking point at Wapping than as a protest weapon. Despite sharing the same streets as the battles against the blackshirts of the 1930s and the dock-owners of the 1960s – or with the Thatcher government elsewhere over the coal mines – ours was fundamentally a war about print. It was a war for talkers. Many among the pickets could have passed a Part One degree course in Molotov Studies. Few, David suspected, had ever thrown one.’

‘The chief risk for the printers was of misinterpretation. The Metropolitan Police, or “Maggie’s army” as the pickets jeered, might easily confuse a trade unionist who wanted his hereditary job back with an armed man seeking Socialism. That was a real risk. Mr Hart was just one of those keen to misinterpret the picketers if they could. He used to send in articles for publication in The Times, perfectly typed in 22-point Times New Roman on handmade paper, exposing communists in the newsrooms of other newspapers.’

‘Back in 1984, in the high days of the Right after Margaret Thatcher’s second election victory, he turned the Miners’ strike into an ideological war. He has received due credit (and disgust) for that.’

Miss R interrupts coldly. ‘Yes, there is going to be a play called Wonderland about him.’

‘Is there? I don’t know.’

She looks pleased.

‘In 1986 he wanted Wapping to be like the coal mines. If a picket could be demonised as a petrol-bomber he or she would be. But David always knew when he was struggling. He loved life’s extremes. He was sometimes a fool. In his shorts and flat cap he often looked like a fool. But Wonderland would be the wrong word. He was not a deluded fool.’

‘There were varieties of extremists on both sides of our battlefield. David was on the side of ‘freedom to print’. He always wanted the word ‘freedom’ in his causes. The other side fought for the freedom of trade unions, manipulating language from the other edge of politics, anarchists who played arsonist at night, those who saw newspapers as full of capitalist lies that only print-unions should profit from printing.’

‘Well, it was very profitable for the unions to have monopoly rights to print the very articles they deemed politically unacceptable.’

She taps her feet in impatience.

‘Hereditary monopoly rights were a fact for many print-workers, jobs handed down the generations. Yes, it was unpleasant to pass the picket lines. But many who abused us for entering the ‘Great Wapping Lie Factory’ were like any other heirs to a good thing. Yes, they scratched our cars and called us “scabs” but they were prosperous protesters, enjoying their anger, and did not want anyone to think otherwise for very long.’

‘Pickets came and went for the shortest shifts before resuming their work as teachers, taxidrivers or minders of other newspapers’ machinery. David Hart was not the only temporary attender on the line, not the only demo-tourist who, twenty eight years ago, was standing on the ground below us.’

‘And as I remember now, it was David’s plan that I too should find a black leather jacket and woollen hat and pretend to be a protester for a while. He thought it was feeble to be so close to a historic event and not to get in among it.’

‘During the Miners’ strike he had got “snow on his boots” and learned directly what was being said and done ‘on the street’. That was when he adopted his David Lawrence name as suitable for the Nottinghamshire coalfields. He had travelled hundreds of miles and thought it ridiculous that I wouldn’t venture out a hundred feet.’

‘I refused at first. In 1986 I was Charles Wilson’s deputy, in charge of leaders and opinion and much else. I had a lot to lose from the misrepresentation of such a mission. If it were so important, why was David Hart himself only so occasionally among the pickets? He was too well known now, he said, thinly attempting to convey sadness as well as pride. I didn’t want to be a spy, I argued. He replied that I wouldn’t be spying, I would be seeing.’

‘I gave way and on one Thursday night in June I was down there in jacket and hat. Thursdays were always quiet. The protesters were saving their strength for the weekend, lobbing only the sporadic bottle of green glass, Fantas and 7Ups, all of them probably already excavated now from the pit down below, historical evidence of a kind though unlikely to have been recognised as such by the excavators.’

‘I was sure I was being watched. I looked around nervously for anyone whom I knew or who might know me. I was so nervous that I hallucinated almost everyone I had ever known, from Left and Right, friends and enemies of my father, my first girlfriend, my first would-be girlfriend, Latin teachers, fellow journalists from Oxford and the BBC. Afterwards I don’t recall telling anyone, certainly not Frank Johnson who thought that David was absolutely mad, that I was too influenced by his madness and our idea of what we called history almost wholly deceptive.’

Frank preferred only the grandest historical themes and Wapping, he said, ‘would never be one of those’.

![]()

12.5.14

Today the pit has gone. There is only a small pile of bricks, stones and demonstrators’ rubble on what before the weekend was the short side of a possible pond. Perhaps the developers have already buried what they wanted to bury, or unburied it, or tested for pollution or pollutants, or done the minimum required to prove that there are no remains of earlier settlement here, no shackles of Napoleon’s prisoners of war, no Tudor tokens or relics of the Roman trade in dogs. Whatever they have done they have done it quickly.

![]()

13.5.14

Don’t think I spend all of my time staring at diggers and dumpers. I read book reviews, I edit pages. Yesterday afternoon I was a mile away from here on Fleet Street at a Memorial Service, remembering a man who never passed through those old Wapping gates, one of my very first newspaper bosses, an editor from the old Sunday Times who stayed outside when the time came for the then new age.

Ron Hall, an opera-loving mathematician, a master of headlines and Greek wine, worked for Harold Evans, the revered editor who gave me my first newspaper job. Those who praised Ron bemoaned what happened here in 1986. We sang rousing hymns and remembered what newspapers were like two revolutions ago.

These were the journalists, judged then and since as the greatest of their kind, scourges of political scandal, the kind whom Woodrow Wyatt, flatterer of the powerful, and Frank Johnson, comic master of parliament, liked least, the kind whose influence on me and The Times they disliked even more. In some ways I wish that Frank and Woodrow had been there. We could have had more of the conversations we used to have about what journalism was for. But they would not have been there even if they were alive.

From a polished pew I watched grey re-enactments of my earliest days as a journalist in our pre-Wapping home, young meteors now old, men and women with the same ways of mocking, sniping and sniffing, softer in some cases but not in all. In the latecomer’s seats I thought I saw Miss V, my oldest friend, that girl who never quite became a girlfriend, daughter of that first man of the Right I ever knew. I could not be sure.

It was quite possible that she might have been there. Those journalist giants of their age were the first who knew me outside of Essex and Oxford also to know Miss V, a regular visitor to our disputatious newspapers, supporting the trade union side as she had always done when we were young.

![]()

16.5.14

On a rainless afternoon the outlines of the pit below are visible again. Beside them is the yellow JCB which dug and returned the earth. Seen from up here, the rectangle has returned, the proof of how aerial archaeology works, by the watching of clay dry. The light is so bright that the two lines of fir trees between the fence and the former hole are of sharply different colours, the one of them lit pale and melon green, the other shadowed like deep forest.

I will miss everything about this view when we are finally removed to our next new home. No one again will ever see it as it is now. The eastern sky of churches and tower blocks, will remain. But the sometime home of the Sun newspaper, the News of the World, the Sunday Times and The Times has today started to fall. The days of dust and preparation are over. The ‘plant’ has begun its collapse to the ground, mingling thin white dust with the air and thistledown of Spring.

![]()

18.5.14

Miss R arrives early this morning. She goes straight to the white chair I have brought in from outside and puts her red cap down beside it. The piles for the removal men do not worry her now. She separates her own piles, notes the plastic match between her seat and her wristband, picks up a book, flicks through some papers, looks at some photographs of me in fat men’s suits.

‘When did you first hear of Seneca?’

It is as though she is talking about Thatcher, Millar or Hart. She asks her standard question. She checks the piles of books and notes, the spilling brown-inked letters, the variously labelled Seneca files.

Is the man from Cordoba on her list? I am ever more used to answering her now. She seems to know some of my answers before I give them. But then she is a researcher. She has done research.

‘I first heard of Seneca on the same day that I first saw him.’

She lowers her chin like a satisfied teacher.

‘I saw him when I was still a child. He was made of wood but no less frightening to an eleven-year-old for that.’

‘Go on.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes, I’m sure. We have time. I want it all.’

I look out of the window. I point down the river, calling out a catalogue of place names, listing dots on the map before the Thames becomes the sea, the Wapping Canal, Isle of Dogs and Millennium Dome, Tilbury, Grangemouth, Southend, a twist to the north to Walton-on-the-Naze, a place of bungalows, breakwaters, bingo, beaded net curtains and balsa wood.

‘I’ll begin with the balsa.’

Miss R sits back. Everything that happens in this story began in Walton, the seaside town that throughout my Essex childhood was neither Clacton (rough with dodgem rides and slot machines) nor Frinton (too posh, not even a pub) and thus the place that my parents might comfortably take me. Without my experience in Walton I might not have experienced Wapping or Cordoba at all.

‘So yes, in 1962, the year when I first saw Seneca beside the sea, it was the wood called balsa that began it all, the soft, pale wood that grows like weed in South America but to me was the precious material of models, of aircraft, boats and castles. Anyone then could make a car, an abbey, a jet plane, a place of inquisition from balsa. Mr V, the father of my twelve-year-old friend V did exactly that, although he did not show all of his work to her, only to me.’

‘This V was the girl with whom I was then trying to spend most of my time. Because V was her name I knew her parents by the same initial. She wore pale skirts above pale knees, wide belts and a necklace with a single agate stone. If I had been more free I would have followed her like a dutiful dog. As a dutiful schoolboy I tried to follow her as best I could.’

‘It was a wet Sunday in May, a day like today, pebble-dash dampened by warm rain, old ladies on their way to the Odeon, inky clouds over the nasal peninsula that gives the town its name. East London is part of the east of England, the part where I was born but do not live now. On the east side is where this story stays.’

‘Seneca was, as I saw him first, as real as any of the players in my story when they were alive, even more equal now. In his same first scene in the same pale room behind the same covered windows, like every horror-comic hero from a childhood, Seneca has stayed the same.’

She picks up a pile of letters and sifts them through her hands.

‘So this is how it was and still is. My wooden Seneca is a Roman in his early sixties, about the same age as I am now, though heavier in the face than the self whom you have come to see, sun-blasted, dark-eyed, shocked, a frightened man who is used to frightening others, a rich man who wants to be less rich, suddenly much less rich, an artist who has prospered by giving political advice but who no longer expects either to prosper or to advise.’

‘On the face of this Seneca there is damp and cold in every crevice, fear visible in the wrinkles that run like wastepipes, right and left, on each side to where his hair grows high above his ears, hidden in the rolls below his chin, only imaginable within his phlegm-filled throat, a man in a crisp white toga that is quickly becoming creased, a man asking a favour while fighting for his life.’

‘Despite the passage of half a century this balsa scene in a library in a model palace is as solid in my mind as is Dockland brick on the ground. The walls are made of boxes the size of matchsticks. There is a tiny chest of overflowing scrolls. The balsa Seneca himself is barely more than a curved stick; with him is a shorter, stout-stomached man, the Emperor Nero. The man who first showed me this creation added parts of speech and speeches to give his human figures life. Without those words I would have known nothing. A knife on balsa, however sharp or subtly used, does not show terror or pride.’

‘In every book about Seneca (and there are dozens of them here about to be boxed and moved, hundreds more in more learned places) the writer explains that the family Annaei came originally from Spain, that the father was a teacher of speechwriting, that the eldest son earned a bit-part in the Acts of the Apostles, a nephew in the history of epic poems but that the middle son became the star, the power-broking artist who swayed the fate of an empire.’

‘Those history books were not, however, what brought Seneca and me to our first time together. I was too young for them in 1962. It was Mr V, leaning over the table on which he never ate, who explained to me why the tutor of Nero’s childhood, the writer of his speeches, the calmer of his whims, the profiteer from his policies, was at this moment at the most perilous point of his life, standing (as in my memory he still stands) beside a balsa couch, his heavy-lidded eyes dipped down, waiting for a signal from the reclining young tyrant that he might speak. That was when I first heard Seneca’s name, not a very flamboyant name, not a Spartacus or a Cleopatra, a name that nonetheless, like those others, stayed.’

Miss R turns and traces a circle with her hand.

‘Seneca and Nero are together and alone, unusual positions for an emperor and a victim. Nero is not on a throne and that too is a concession to his former teacher who, when permitted, can look directly at the thick neck, thin lips and light grey eyes of the man to whom he once taught the arts of persuasion.’

‘What exactly is going on?’, she asks.

‘In 62 AD or 1962?’

‘Both’, she barks.

‘In 62 AD. Seneca has for thirteen years been the closest man at Nero’s side. It is eight years since, as a boy of seventeen, Seneca’s pupil succeeded to the throne of Rome.’

‘During this time there have been ominous changes. Seneca’s job as tutor came from Nero’s mother, Agrippina, whom Nero has just murdered. Seneca’s power has been assisted by a head of the palace guard who has just died from an infection in his throat.’

‘In his eighth year of absolute power Nero wants to be an artist more than a statesman – and the presence of a political adviser who writes plays and philosophy is an irritant, a reminder of a rival. The Emperor, his hair yellowing, his legs thinning, has come to prefer more ruthless flatterers. Seneca wants permission to retire. He has no family in Rome except his wife. There was a son but he has long ago died.’

‘Seneca wants escape, nothing more than escape. Will Nero let him go? Will he thank him? Will he have him killed? Will he watch him be killed? Those questions invite the damp and the cold even though the afternoon is hot.’

‘So what was the point in 1962?’

‘That retiring from a political court is as hard as arriving in it. That was the first political lesson I ever heard. V’s father whispered it into my eleven-year-old ear that day behind the net curtains of his bungalow by the sea, twisting his knife towards a fleshy lump of wood. Neither Hitler nor Stalin liked men to retire of their own free will. No more did Claudius or Nero.’

‘This Mr V became my teacher as well as seaside puppet-master. The balsa Seneca thanks the balsa Nero for the opportunities that have made him rich and offers to return that wealth (or most of it) to the place from which it came. He recalls his humble origins in Cordoba, in distant Spain and pleads to be able himself to return to where he began. This is the right time, he says. To do and acquire more would offend the laws of due proportion.’

‘Nero listens. He screws his eyes. He gives the look of an old friend and the answer of an executioner. His face is hard to read, just as Seneca taught him to make it. He turns his old tutor’s arguments back on him, just as he once learnt to do, just as his mother once wanted him to learn to do.’

‘Nero does not need to prove a case only to take his tutor’s case apart. He speaks of his own youth and Seneca’s useful age, his continuing desire to be warned when he is on slippery paths, the inevitable incomprehension that will surely occur if Seneca suddenly disappears. The careless or unkind might even allege that Nero has frightened him away – and that might be a damaging charge to the Emperor, surely an outcome that Seneca does not wish.’

‘The conversation ends. The skin from Seneca’s cheeks collapses over his ears. The lines across his chin are like the thin spokes of a wheel. The face, like the man, is lessened by the loss of imperial light. Nero can return to writing, to his new wife of whom his mother disapproved while she was alive, and to dressing men and women in pitch-dipped gowns and burning them in his gardens. Seneca can bathe and change his own sweated clothes. His career does not abruptly end. For a short time it is allowed to fade away.’

Miss R walks to the window and takes a deep breath as though it were open, as though she were about to speak herself. Is she surprised? What was she expecting? This is not a story I have ever told before.

‘Was seeing Seneca like that a shock?’

‘Not entirely. On the way to Walton V indicated in her own indirect way that all might not be quite as I expected. On that grey 60s Sunday, while we waited for the green-and-yellow bus, she warned me both of her father’s ways with Roman history and his record of rages. But I did not understand what she meant. In 1962 I was eleven years old and my knowledge of Rome and rage were equally small.’

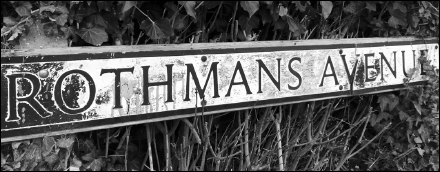

‘That was when Mr V had only recently left the semi-detached house, almost identical to the one attached to my own father’s work, on the Essex clay of the Rothmans Marconi estate. V’s parents were deemed “separated”, a rare, cold word in that place and time. V was a year older than me but many years wiser. When she told me to tread carefully with her dad it did not seem important. I listened. I loved to hear her speak. But I lacked experience as well as knowledge of what she was saying.’

“‘Sheltered’ is how my childhood would now be termed. Anger was as alien as extravagance. My primary school teachers would bluster from time to time but not at me, and not at V either when she was in the same class at the same school the year before. My own father, Max, a recent escaper to Essex from the Nottinghamshire coal-lands, was the mildest of men, even milder than the gentlest teachers in our gentle Rothmans estate where men designed military machinery.’

‘V’s father was a laboratory technician. He made hard steel models of military radars during the day and soft wooden models of almost anything else by night, nights that for the past few months he had been spending some thirty miles away by the sea, in the town that Daniel Defoe called Walton Under the Nase, a more accurate name, I have always thought, for a place permanently tumbling into the sea. Mrs V (as I always knew her) had ejected him from the family home. I did not know how or why.’

‘It was rare for V to agree to see me on a Sunday but, when her job was to visit her estranged father, she found me useful. My reward was to spend bumpy hours looking at her legs in her weekend-shorter skirt. The price was to be in Walton at 1 o’clock on that October day, sitting at the high end of a steeply sloping sofa, waiting too long for lunch, admiring wooden walls and pillars in the window of a bungalow glowering at the sea.’

‘I was nervous because, as on the two previous days I visited Mr V, I was not supposed to be there. My mother, the prouder of my parents, an escaper from the city of Nottingham itself rather than its surrounding “sticks”, disapproved of the laboratory technician and his daughter. Our Rothmans estate was home to engineers and mathematicians from all over the country, each of them chosen for their part in making radars for the postwar safety of the West. With no common roots, ours was a world of hastily defined social distinctions – and for us in the lower middle of the range of classes, those who were a fraction lower down were deemed much the most dangerous.’

‘All the children of the military engineers learnt their letters and numbers, mostly numbers, in the same classrooms of Rothmans school, a single-storey block of bricks. But outside school I was supposed to face slightly up the social ladder rather than slightly down. Laboratory technicians like Mr V were a little lesser than electrical engineers like Max Stothard and it was better, my mother said, that I stayed away from where they lived, either as man and wife together or, yet worse, apart.’

‘The Seneca scene occurred on the third visit by V and me to Walton. We were late. The back seat of the bus had spent more than an hour on the roadside, the peculiar indicator then to other buses that it was over-heated, under-dieseled or in some other sort of distress. When we finally reached the right street, V asked if I minded going on alone while she found a shop and bought some sort of peace offering on behalf of her mother.’

‘I walked up the crazy-paved path through a lawn of artificial grass, the door opened, and Mr V smiled at me like a white mouse and pulled me in. He said nothing. He shuffled me beyond his hall of small wooden model toys, past the cloakroom in which he had built a precisely scaled model of our estate (I could see my house and its own plastic grass: I could see the house that once had been his), and into the front room where there was just one large model – of Roman pillars, pilasters, porticoes, peristyles and ponds. Behind thick curtains, a double row of net that gave a dirty, salt-stained light, modesty even by the standards of Essex in 1962, was a peculiar imagining of an imperial past.’

‘V and her father were alike in many ways, both blond and pale-clothed, pale-faced too, puffy around the arms, like the cream chewy toffees that the travelling sweetshop brought us, like the balsa itself which in this house, unpainted and unvarnished, filled every visible space. He was a blotting-paper man, she a sheet of chalk, a neatly matching pair except that, after half an hour, still only one of them was there. V had not returned. There was only one of the V family visible on that May afternoon, in cream slacks, short-sleeved cricket sweater and an almost colourless aertex shirt.’

‘I waited for him to speak. On the first of my previous visits he had asked me about my senior school plans, just as a kindly neighbour should do, querying what subjects I was most looking forward to. Latin, French, Physics? Not Physics. On the second occasion he asked why I thought that the Rothmans estate had been designed in the way so clearly shown in his model. Why were there larger detached houses by the school and smaller ones, joined to one another in twos, threes and fours further away? Ours were both part of the middle but not in the same part of the middle.’

‘What was meant by middle class? Did I see myself on the Right or on the Left? At some time soon I might have to choose. On the first visit we ate egg sandwiches on the sofa of his kitchen, its walls as luridly coloured in red and yellow as his front room was white. There was a green parrot in a gilt cage. I told him that I was looking forward to Latin because a teacher had already introduced me to it and because my grandfather had left me a Latin book.’

‘The second time, while V was slowly making tea, he told me that the estate was a sign of order, a structure of people as well as bricks. Order was a necessity. His voice was barely audible and I did not then understand even what little I could hear. I was dutifully waiting only for the explosion that V said would one time surely come. When we left for the bus stop an hour later, I was still waiting. As we left I suggested to V that she had exaggerated her father’s rages, a jibe that cost me excommunication for the whole, long journey home.’

‘Only on the third visit did I hear the wooden Seneca plead for his life.’

![]()

19.5.14

Miss R left hurriedly last time. She had to take a call. Her visit today seems similarly to be interrupted. She arrives noisily and adds a suitcase to the patterns on the floor. This time she prefers not to sit. She arches her back against the wall, a position permanently poised for a strike.

I am ‘not being helpful enough’. Her mother is buzzing her phone. Her mother is a nuisance. I am a nuisance too. She wants to get back to her assignment. She has a new list of questions.

I look at her as though to protest. But I have begun this. I will go on with it. I am a bit surprised at my own patience but these are strange days, useless for any work of my own, not till I get to Cordoba.

I could have answered many more of the questions if David Hart had not developed Primary Lateral Sclerosis, his rare form of Motor Neurone Disease, and ended his life, unable to speak or walk or make any more than the most limited use of his voluntary muscles.

David was one of those who knew about ‘the letter’, the three sheets of paper on Mrs Thatcher’s table, the one directly outside the door to her Downing Street flat, where her closest confidantes could leave the most private things. He knew about ‘the interview’, too, or rather the side of it that I at The Times did not know.

‘Tell me about this letter – and about “the interview”, the interview “given by the Rt Hon Margaret Thatcher FRS MP to The Times on Monday 24 March 1986”. She speaks in quotation marks, reading from her list.

I cannot tell her much. David claimed to know everything about both. I can tell her merely that ‘the letter’ was important for the brutality of the attack on its beleaguered recipient and her deep hurt in response. There was hurt from ‘the interview’ too.

Miss R is right to be interested. Personal harm is at the heart of politics. So very few people ever knew about her hurts. David knew because Ronnie Millar told him. But I never got to ask Ronnie enough about it before he died, or to ask David before he became weak and voiceless, typing a little but mostly only medical queries, asking how Stephen Hawking’s condition was so slightly and significantly different from his own, googling with a single finger joint, sucking Chateau Lafite, his favourite, through a straw. Nothing can bring back answers to questions never posed.

The kind of history happening outside my window today is so much clearer. This is land beside the Thames outside the Roman city walls that I walk past every day, land for traders, sailors, stevedores, soldiers, criminals, their guards and the desperately poor. White flakes fall thickly now on the ground around the disused gates, exposing other pits of past construction. Barrows appear below car parks.

Plastic sheets protect the walls that are to be kept, the old brick walls, fifty-three courses of grey and gold that were here before the newspapers came. Only the red brick plant itself is set for immediate collapse. That will soon be history in the more usual modern sense, neither the uncovering nor questioning of evidence but the newly obliterated ‘you’re so history’ kind.

It is amazing for me to see this. Hardly anyone else at 3 Thomas More Square seems to find it so but hardly anyone else here now was in Wapping when it mattered. There are hundreds of newspaper-makers above and below me in this office tower and everyone wants as fast as possible to get away. The fall has begun. Even on ground so often refilled over two thousand years this is an event.

![]()

20.5.14

I am expecting more questions about Margaret and the letter but instead she wants to know yet more about the V family.

‘They were so different from my own’, I say.

‘Really?’

‘The difference was not in every way. My father and Mr V looked quite alike. Mr V was somehow whiter because he was blond but Max Stothard was pale too, sharply so, where his hair stood against his skin. Maybe all adults looked the same then.’

‘My father had escaped a secretive family of Nottinghamshire Methodists to take a degree in Physics. Mr V had taught himself. They did not like each other but that was not a serious thing. Any casual observer would have seen interlocking cogs in Britain’s military machine for making radars.’

‘The big difference between them was the place of argument in life. In 1962 the Vs introduced me not only to politics, which eventually brought me to Margaret Thatcher and my Senecans, but to books of all kinds. The box room at the top of their stairs, the room that in our house was reserved for me and our suitcases, was their one place without balsa.’

‘Instead, they kept there the condensed versions of every sort of book from Marx to Miss Marple, Gibbon to Gertrude Stein, Kingsley Amis and Kingsley Martin, crime novels, classics from French and Russian, “Readers Digests” mostly, “Campbell’s” as Mrs V called them, stories without the added water, just like the soup.’

‘These books made V something of a polymath as a young girl. She could sound as though she had read almost everything. It was always dangerous to have an argument with V about what happened in a novel. Since none of us had yet graduated to discussing whether books were any good, or how or why they were any good, V was our very own professor of Politics and English.’

Miss R scrambles for her notes.

‘V knew books that Mr V and his wife had already absorbed for the corroboration, or otherwise, of their political hopes, hers well to the left of his. Copies of Dickens and Woolf were not merely Campbelled and digested but gutted, chewed and spat back between their plastic covers. Sometimes there was evidence of fatherly pleasure, the Annals of Tacitus on paper so thin that his ticks for Seneca dented a dozen pages behind each one.’

‘Or there were crosses of dissatisfaction, pages brown-inked “progressive cant” or ripped away completely. Words from the past were as serious as any screams of the present.’

‘And your own family?’

‘Between the Stothards and the Vs was not the tiny gap in employment status that exercised my mother and father, my mother most of all, but the massive gulf between silence and the clashing of ideas. V’s was a family where books and politics were one, a conservative vs two socialists at a time when under the Conservative Party we were told we had surely never had it so good. In my own house there were only five books and never any talk of politics at all.’

‘But you kept in touch with Mr V?’

‘For thirty years after that long-ago time he sent postcards and letters written in pale brown ink, mainly in the 80s when he noticed some egregious failure of mine to support Mrs Thatcher’s position in an argument, afterwards when his target was some incompetent whom he thought I might influence, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (the Work always deleted) or the Governor of the Bank of England (on a bad day he deleted England).’

‘Ours was a one-sided correspondence.’

‘Are these all of them?’

‘Everything that is left is here, but not for long.’

She shuffles some frail pages.

‘I replied to Mr V only a few times. He did not want replies in 1987 any more than he had in 1962. My one attempt to answer a question he posed about the world’s oldest parrot fossil (found a few hundred yards from his front door) produced a fusillade of abuse. He wrote like a man with a gun, “fire and forget” as the missile men of Marconi used to say.’

![]()

21.5.14

Miss R is calmer this morning, her hands almost still and retracted neatly from sight. She has time. Perhaps she knows she is in the right place. Her new patience is like my own in these days of limbo.

Next on her list is Ronnie Millar, my man ‘who put the words in Mrs Thatcher’s mouth’.

‘Was he a friend to David Hart?’

‘Ronnie said so, especially at the start.’

Miss R says nothing more until she asks with her most mechanical voice, crossing her legs, tapping her feet, like a moving mannequin in a shop window: ‘When did you first see Sir Ronald?’

That is the question on her list, the one she should have asked before.

‘It was at the end of 1980 in my second year as a journalist’, I reply.

‘This was two years after I first met David but well before I had any power, indeed before there was any likelihood of that. I was still not yet thirty. It would be six years before the newspapers moved to this watery patch of London and I moved to the “executive Mezzanine”. Yes, I was on the other side of town then and, as it seems today, on the other side of time.’

‘Ronnie Millar was my earliest guide into the court of Margaret Thatcher. When I first spoke to him it was on his sixty-fourth birthday, only a year older than I am now, and he said that he had her on the piano. He later somewhat changed that story. He did sometimes change his stories. But the time of my telephone call to him is clear in my diary, the afternoon of his birthday, November 12th,1980, and he had absolutely no idea then who I was.’

‘I was sure of that. Unlike David he had not sought me out. At breakfast I had seen his name on the Court and Social pages of The Times. As the Prime Minister’s speechwriter he had won an official eminence that plays and films had never brought him. Later, at lunchtime, I shared a bottle of white wine with a fellow reporter, both of us anxious about where our next story (though, in those opulent days, not our next bottle) might come from. That afternoon I looked up the name Millar, R in the telephone directory, a source then of contact details inconceivable today, and called to wish him Many Happy Returns.’

‘A lilting voice immediately mentioned Mrs Thatcher and the piano. I said that I was pleased that she was sitting on the instrument and not under it. There was a pause, then a light sound that I optimistically took for laughter: “My dear, we’ve been rolling around on the carpet for an hour”. I asked if I might come round and talk for a birthday hour about life, work and Prime Ministers. Absolutely, came the reply. Why not right now?’

‘Two hours later he had given me some jokes and stories that I could use in the Sunday Times and many more that I could not. For my reporter’s notebook he rejected any suggestion that he and “dear Margaret” were like characters from Private Lives: “I mean to say, we don’t roll on the floor while a record player blares out ‘Some day I’ll find you’”.’

Sir Ronald Millar

‘I pointed out, politely I hoped, that he was the one who had made the comparison. He spoke about her the whole time as though she were the star of his Robert and Elizabeth or Abelard and Heloise, one of his once famous musicals, a singing poet or nun. He treated me as though I were still some sort of theatre critic: what did I think, how could she improve, why was the rest of the cast so jealous and useless? I don’t think that he had then met many journalists. We drank the champagne that she had sent round, snipping the dark blue bow around the bottle’s neck with nail scissors.’

Miss R frowns. She is becoming anxious again. She begins to look as though she has been in the same position too long, her legs in tight trousers today and splayed over old Oxford lectures.

‘You’ve told interviewers this before’, she says.

There is a mild menace in her tone.

‘I am saying only what I remember’, I reply.

‘You mean, what you have said before to other people?’

‘Partly, but also what I wrote in my notes.’

‘Has anyone else ever seen those notes?’

‘No.’

‘Did Sir Ronald talk much about himself?’, she asks.

‘I have told you all I can remember. I’m sure that I was drunk’, I say, ‘and so was he. It was his birthday.’

The mention of drink makes me want a drink now. I would like to offer Miss R a glass of wine but Wapping has always been hostile to wine. Office alcohol was one of the vices that in 1986 the new world of newspapers was meant to leave behind.

We sit against the darkening sky, each of us with a plastic cup of water.

‘Ronnie never gave much of his privacy away’, I say, ‘not even when we were alone. He had a preference for personal discretion that contrasted sharply with his indiscretion about others, the MP whose philandering would always keep him from the Thatcher court, the minister who collected miniature spirit bottles and had tried to interest Margaret in this enthusiasm.’

‘With some difficulty I learned about his schooldays at Charterhouse. This was Charterhouse in Surrey, successor to the London site occupied by numbered pensioners where we said goodbye to Richard Brain. With even more difficulty I learnt how in 1940 Ronnie had been a classicist at King’s College, Cambridge (his fees paid by a secret benefactor) before first, Her Majesty’s navy and secondly, Her Majesty’s Theatre had claimed him as their own.’

‘He approved of secret gifts?’

‘Yes, so did Seneca. They were the purest kind’.

‘His first political speechwriting was for “Mr Heath”, two words always spoken softly at this time, but his commitment to the art came with “Margaret”. His voice was low that very first afternoon. The piano was silent. His mother was asleep in the second bedroom.’

‘On his bookshelves were three copies of Sophocles’ Antigone in Greek (one of them marked up phonetically for the actor playing the part of Creon, the wicked uncle), some blue-and-white scripts of his own musicals, a paperback of the Satyricon in English, the copy now here in my office, and two OCTs, both bound in blue leather, some of the Cicero speeches that have long been deemed “improving” in certain sorts of schools and some of Seneca’s letters and plays that mostly have not.’

I look down into a large brown box and pull out an Oxford Classical Text to show her what I mean by an OCT, a severe volume of Latin without a word of English encouragement. I add that on the lid of Sir Ronald’s piano, reflected in the black polished wood, was a photograph of Britain’s first female Prime Minister in a silver frame.’

‘For the next seventeen years, as he grew ever closer to his “Margaret”, we spoke every week, sometimes several times a week. And yes, he and David seemed to be friends as well as allies at the start.’

‘When did you first notice them together?’

I am beginning to anticipate Miss R’s questions before she poses them? I reply quickly.

‘It was in the Falklands War. This was the event, more than thirty years ago now, that saved Margaret Thatcher’s career. It was also the first event that alerted me to your four courtiers, the ones who became my Senecans, how they worked together, how they did not and how sometimes they failed to know the difference.’

![]()

22.5.14

Miss R has found the Seneca pile. She opens a battered red book, a Loeb edition of essays, and reads the titles of the chapters aloud.

‘On the Value of Advice, On the Usefulness of Basic Principles, On the Vanity of Mental Gymnastics, On Instinct in Animals, On Obedience to the Universal Will.’

She speaks mockingly with pauses as though waiting for me to stop her.

‘Which of these is your favourite? Did the Senecans have a favourite?’

‘The Senecans did not yet exist, not as a group’, I tell her. ‘You are losing your chronology.’

She looks anxious as though that is what she has been particularly instructed not to lose.

‘At the beginning of April, 1982, Millar and Hart were still merely separate names in the contacts book of a political reporter. I knew as little about their contact with each other as I did about the Falklands. They knew nothing of the Falklands either. No one did.’

‘But the Argentine invasion of our South Atlantic islands was unexpected, embarrassingly so for the beleaguered Thatcher Government. The Prime Minister might either be blamed for allowing an enemy in or praised for throwing an enemy out. Who could know which? There were suddenly big prizes on offer to those who learned to care about South Georgia, those who could appreciate what a transforming story this might be. Millar and Hart lacked nothing in “animal instinct”.’

‘Yes, I see. Which animal were you?’

‘You decide. Generally I prefer birds.’

‘I had moved on a bit since that day in 1980 when I first wished Ronnie his many happy returns. I had risen from the reporter’s room of the Sunday Times on the Gray’s Inn Road into the job of leader-writer and factotum editor at The Times next door. This brought with it a junior observer’s position at Margaret Thatcher’s court. I was lucky. I argued about M1 and M3 and other ‘money supply targets’ with motorway names. I knew about the throw-weight of missiles that might threaten Moscow.’

‘On the afternoon that war began I was also one of many journalists still trying to find the Falklands in an atlas. Our designer had a book of penguins from which he was hoping to produce illustration for the empty sea. The islands themselves, numerous and spread throughout the unexamined pages, were hard to discern. Some of the names were in Spanish, some in an obscure numerology. No one cared. There was a much more important football World Cup in the offing and the Princess of Wales was for the first time pregnant.’

Miss R presses her elbows to her knees, leaning forward as though this is my first fact of real interest.

‘One ordinary morning Charles Douglas-Home set off grumpily for the Ministry of Defence. My Editor at this time had a limited patience with officialdom, a limp and a lump on his head, the latter two signalling the cancer that would kill him just before we left for Wapping. Before he left the office there were other anxieties on his mind too, the imminent visits of the Pope and President Reagan, Margaret Thatcher’s maladministration of her own policies, her equally imminent electoral defeat, and the health of his cousin, the Princess.’

‘By the time that he returned, his limp renewed as an uneven stride, there was only one issue. We were “all Falklanders now”.’

‘Obedience to the Universal Will?’, says Miss R coldly.

‘On Fleet Street even those who despised principles on principle discovered righteousness and self-righteousness with precise simultaneity. In the newsroom we just had to find out precisely where all “we Falklanders” were supposed to be living. It was all quite comic before sailors began to die’.

‘Yes’, she says.

![]()

23.5.14

The stage below is shifting as though for some new scene, maybe a new act. The protected trees around the pit are now part of a fence. The wooden boxes were moulds for concrete cubes and have fallen away. I was wrong last week. There are no new trees. There never were any new trees, only posts. The site of the pit now holds a cage for what is perhaps a particularly valuable JCB. A picket could still hit it with a carefully lobbed bottle.

This time, for the first time, I am looking from my window at the right time and can see Miss R walking towards me, watch her pick her way past the relics, watch her taking photographs, talking into a phone. She has the shoulders and colours today of a toy figure, a poster-paint postman on my old Essex train set, bright blue between the square red plant of Lego and our Rum Store, a plastic model farm.

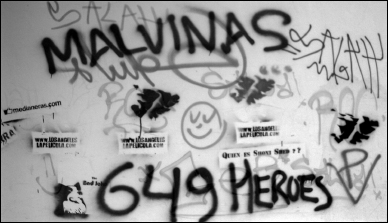

‘Two years ago I was in Argentina myself’, I begin, taking the initiative after ten minutes of her desultory sifting through books and papers. She puts down her notes. She does that when I abandon her chronology.

‘Three decades on’, I report as though to a newspaper news desk, ‘there are still Falklands protests, “Fuerza CFK” protesters supporting Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, a President who likes to compare herself for glamour with Margaret Thatcher and John F. Kennedy, while decrying their views. They wave their placards at everyone whom they deem to be British, a group that, on the morning I was there, included a Danish couple, their small dog and a thin Canadian with a Father Christmas outfit in a carrier bag.’

‘There are also balsa trees’, I add.

She grimaces.

‘Inside the army museum there is a map on the wall of the Salas Islas Malvinas which would have been very useful to us at The Times in 1982. It is not a very big Sala, more of a corridor between massive celebrations of victories against nineteenth-century Brazilians. On one side there is a boy’s bedroom of plastic aircraft, Mirages and Lightnings, on puppet strings. On the other a glass case contains three blue-ribboned medals, a model Mercedes truck and a green bottle of Tierra de Malvinas dry mud.’

She closes her eyes.

‘A sign to the toilets leads the careless eye away from a sailor’s hat with the name General Belgrano, a bright colour photograph of a warship and the names of 323 “heroes” who were drowned when Margaret Thatcher ordered torpedoes against a “fleeing enemy”. A plastic Sea Harrier completes the scene. The sinking of the Belgrano was Millar-Hart-and-Wyatt’s first joint move in my direction, May 2-5, 1982.’

Miss R opens her eyes, picks up her book again and begins to write. She has a curious knack of asking for explanation without saying a word. I give the answer that I think she wants.

‘The British Task Force (a curious name that for reasons unknown had attached itself to the available ships of the Royal Navy) had by early May, after many a nervous moment, reached its distant destination. The diplomats were in disarray. The war had begun. A torpedo in the side of the battle cruiser, Belgrano, a ship in the wrong place at the wrong time, seemed a reasonable response to reasonable fears.’

She makes an electronic note. I am back on the right lines.

‘News of the sinking arrived slowly. Slowly too there emerged awkward questions about our target’s position. This was not a total war. Diplomacy still decreed its wrong and rights. Those who knew about ‘rules of engagement’, including the newspapers’ Defence Correspondents and their friends at the Ministry, said that the Belgrano was outside the combat zone and moving away from the Task Force at the time, that the attack was a disgrace, should never have happened, that admirals’ hats should roll, ministers too.’

‘There were politicians in all parties who hoped that a sunken ship might even sink the Prime Minister. My first call was from a Labour friend, ringing to explain how helpful this former cruiser could be to her cause. She was not a senior figure. Her name was Jenny Jeger, the J in ‘G, J, W’ a newly fashionable company formed by a young Socialist, Liberal and Tory to lobby on behalf of companies.

‘Individually these three were not important: G, a languid Liberal of the then dominant Scottish aristocratic kind; J, a bouncy niece of a battle-hard Labour aunt and MP; W, a witty art collector who had worked for Ted Heath. But together they represented what was still the orthodoxy of all party elders, a yearning for the days before Margaret Thatcher was invented, a return to normality that could surely not be far away and that a war crime in a botched war might bring closer.’

‘In Margaret Thatcher’s inner court this was a problem. Millar and Hart were just two of those who had the task of telephoning the press, pioneer Falklandistas, part of a campaign of military precision to ensure us that the experts were wrong, that the Belgrano was an acute danger to our sailors, that it was ‘zig-zagging’ to evade pursuit. How could anyone tell in what north, south, east or west was its due destination?’

‘When Ronnie called his voice was more than usually like Noel Coward’s, strained in the intensity of the role he thought might impress me most, the patrician head of an Oxford college, disappointed in the cleverness of his charge. He said loftily that I should see our ships as scholarships and that, if I did so, I might better prize their survival.’

‘Beware the vanity of mental gymnastics’, says Miss R softly.

‘Yes, that was more or less what he was trying to say.’

‘David Hart, decades younger, fit and full of purpose, was on a slightly different track. He arrived at the front door of The Times in an armoured car. SAS colonel? Cruise-ship crooner? He attracted suspicious newsroom attention.’

‘Once behind brown wooden doors he was calm and confidential. He had already advised the Prime Minister that a major Argentine ship needed to be sunk. It was what the people wanted on “the street”, those beyond the political class, the football fans who, when Britain played Argentina, wanted a result. He wanted one or two aircraft too, definitely more than one, a black eye for “Johnny Dago”, a carefully calibrated black eye.’

‘“The sinking should be cause for celebration”, he confided in a whisper. “GOTCHA” ran the first-edition headline of the Sun when the news arrived. There was also, of course, the very serious threat to the Task Force from the Belgrano, the ease with which a ship might launch weapons while appearing to be in flight and the fact that, as a man of scholarship (was that the only kind of ship I cared for?), I should know better than anyone about the Parthian shot, the arrow shot from horseback by enemies of Rome in a seeming retreat.’

‘David did not deliver his message as succinctly as Ronnie had. But the taunt and purpose were the same. Later on the same day our columnist, Woodrow Wyatt, followed their lead. Between them they ensured that The Times saw the issue as it was meant to be seen, while avoiding any tasteless triumphalism that might trouble our readers.’

‘That was not the last time that they worked together but for a while it remained the clearest.’

Miss R turns to a new page and draws two horizontal lines in blue.

![]()

26.5.14

‘After that it was Ronnie who became my closest political “source”, the word that journalists use for the most useful of their friends. David knew less and was less reliable. Ronnie seemed to know everything and events usually confirmed what he said. In the following year, 1983, we were together in Blackpool for the fall of Cecil Parkinson, the party chairman who led her we-won-the-Falklands election campaign, a pale and flat-faced man, the kind she appreciated most and hated to lose.’

Miss R stares into the outer office. A pencilled picture of a past TLS editor stares back at her. She blinks first and bids me to go on.

‘It is odd how so many of Margaret’s allies looked the same, the polished brows, cheeks that made mirrors, noses that in profile almost disappeared. Cecil was the model but I am remembering too Lord Hanson, the “asset-stripper” who helped to finance some of David Hart’s campaigns, Lord Quinton, the President of Trinity College, Oxford, who offered Roman philosophy and jokes – blurring faces now, men, always men, in whom she could see her own reflection. I am not being unkind to those men. It was Ronnie himself, who carefully shared this look, who first observed the pattern, treating himself like a casting agent, as though he were outside his own appearance, judging, deciding, noting what made Margaret feel good and what did not.’

‘The Times, to his great regret, was the tripwire for his “dear friend” Cecil, whose mistress, Sara Keays, gave us an “exclusive interview” about their love affair, her pregnancy and his failure to leave his wife. This was a story that most of us on The Times too would prefer to have analysed than reported. Even the journalists who were given “the scoop” were embarrassed. But there was nothing that they could to stop or even control it.’

‘The front page on the last Conference day was sensational. The Times was inexperienced at sensation and some of its Tory readers, an angry crowd of them harassing me on Blackpool Station, said that they would never read the paper again. What upset Ronnie most was that the revelation ruined the impact of the Conference speech. No one cared about his carefully crafted prose when there was a scandal.’

She smiles.

‘In 1984 we were together again at the other seaside end of the country, in Brighton. He was the first to give me an insider’s account of the bathroom bomb in room 629 of The Grand Hotel, the blood in the rubble, the calm of “the Lady” who came so close to being killed by gelignite in clingfilm. He watched her leave in the back of a black Jaguar, “waving not driving” he said: Ronnie could not resist a literary joke in even the darkest times.’

‘He survived the blast himself, he said, because at the beginning of the week he had demanded a room that was closer to Margaret. It was on the back side of the corridor but he had seen the sea view quite often enough. His first thought as the ceiling crashed and he hit the staircase wall was “My God, the speech” and he collected its scattered pages on his hands and knees before joining the survivors in their deckchairs on the promenade.’

‘Ronnie saw politics overwhelmingly as the product of speeches. Writing for his mistress became the most important part of his life. He was jealous of her attention. He deplored rivals and knew how to make her deplore them too.’

‘He kept in his pocket a cutting of a sketch by Frank that described “the left-right conflict which dominates our time” as the one “between her left-wing speechwriters and her right-wing speechwriters”. It was almost a talisman. He liltingly mocked the chauffeur-delivered jokes from the novelist, Jeffrey Archer. He crumpled David’s cream-vellum couriered phrases too. It was at speech-time that I realised what Ronnie had and David most wanted, proximity to her person, and how Ronnie would never let David have it.’

‘When the two of us were alone together he liked to speak about politics and classics as one and the same. I told him about the sycophants’ lunch and he talked to me about Petronius. He told me about Denis Thatcher’s seventieth birthday party, a “gin and golf” affair where he sat between an unhappy Mrs Parkinson and an unhappier girlfriend of the Son, “Mark the menace” but still less of a menace in Ronnie’s view than the Daughter, whom her father called Carol Jane. Ronnie quoted lines about Trimalchio’s gold-grasping wife, Fortunata, and paused so that I could praise his powers of memory.’

‘A speechwriter needed to be close to his client’s family, Ronnie explained, just as Lucius Annaeus Seneca had been, the first speechwriter in the tradition in which Ronnie saw himself, a manager of Nero’s mistresses as well as one of the very first men to understand the principles of writing a speech for someone else to deliver, the science of it, the setting out of arguments that the writer would not necessarily use himself, the ranking of them in order, the grace notes for sliding from one to another, the way to memorise and deliver the words. What, why, when and how? Both he and Seneca knew why a speech had to answer those questions and how, by weighing the answers, a good speech could be distinguished from a bad one.’

‘Mrs Thatcher’s original voice oscillated in the range between parrot and owl. Ronnie and “one of her PR friends”, dealt with that together despite Ronnie’s belief that he could quite easily have done it alone. It was, in any case, a superficial problem. The permanent danger was that so many people hated her, particularly and most dangerously the people who said that they did not. “She used to spit out her words like my Latin teacher in Reading”, he recalled. “But when you think of the snakes that surrounded her, she should have turned them to stone. “Nero forced both Petronius and Seneca to commit suicide”, Ronnie added tartly, “although that would be quite inappropriate today”.’

![]()

27.5.14

Before Miss R leaves she asks if I was ever tempted from the outside into the inside of politics.

‘What about you?’, I counter.

‘My mother and grandfather were political enough for all of us’, she snaps.

‘Only once did temptation come’, I tell her. ‘It did not stay long.’

‘That moment was in 1985, the year before Wapping, when there was a move from somewhere to put me into a “Policy Unit”. The idea sounds even more absurd now than it was at the time. It would have been a bad mistake for everyone. Fortunately, the Mandarins, as Ronnie discovered, deemed me insufficient of a “team player” and “too liable to confide in others”.’

She is almost out of the door, with her short blue jacket over her shoulders, when she asks a different question.

‘Did you ever meet a man called Sir John Hoskyns, Ronnie’s fellow plotter in the earliest days?’

‘Yes, I did.’

‘Was he really the clearest and cleverest man she had?’ She asks as though reading from instructions.

‘Well, he was the straightest-backed of the flat-faced men, a strategist trained in soldiery and computing. Clear? Yes. Clever? Yes. He produced a paper on how to crush the Left called Stepping Stones which even the boldest thought too bold. He was a good source to me. He trusted The Times in what was almost a family way. His wife was an artist friend of Charles Douglas-Home’s mother, the woman whom both John and CD-H called “the Queen of Norfolk”.’

‘Ronnie and I watched John Hoskyns as Margaret Thatcher drove him mad, as he tried to escape, as she would not let him go, as he tried to escape again and did. She accused him of wanting to hurt her cause by publicly leaving it. He thought that to be a suggestion from a tyrant. Ronnie asked if I remembered that scene where Seneca is trying to resign his offices and the mad, bad Nero refuses to let him go? I nodded. I knew it better than any scene in ancient history though Ronnie did not know that.’

‘I never spoke to anyone of Mr V in Walton. This was also the first time I heard a friend refer even obliquely to Margaret Thatcher’s madness. Her enemies spoke of it all the time.’

‘John wrote her “that cruel letter”, Ronnie whispered. He sneaked to her room like “a ghostly apparition” and left it where she could find it by herself, alone, with no one to help her absorb the shock. A military man in a hurry, he thought she was missing so many chances, letting herself and the country down, preferring her own “intuition” to his own inexorable logic. She had never received anything like that letter before in her life’.

Miss R moves back from the door, lays down her jacket and stops me there, just as I am about to reprise the importance of resignations, attempted resignations, failed resignations.

‘I already know what you are going to say’, she says.

‘What is that?’

‘You’re going to tell me the story of the “slipper wheel”, the warning that the most important position is the one from which you are about to fall.’

She says the words slowly, challenging me to contradict her.

‘Maybe we’ll come to the “slipper wheel”’, I reply.

‘So why’, she asks, shifting direction as she so often so disconcertingly does, ‘do you recall your time with Ronnie so well?’

She moves her shoes closer together, white again today and almost side by side, edging away a pile of Seneca’s essays and letters, On Anger, On Mercy, On the Shortness of Life, On Style as a Mirror of Character.

‘Because, as a young reporter, I took good notes and because today I am older and leaving this office, leaving Wapping and in a mood to remember. Is that not what you want?’

She looks out at the dirty sky.

‘And because Ronnie is worth remembering, worth reassessing. He took his responsibilities seriously, a seriousness that was hidden because he came to be known best of all for his jokes, his style, his elocutio as he put it. He was not a scholar. He affected a genial disdain for the professors whom he had left after his one Cambridge year. But it was dangerous ever to assume his ignorance. He once surprised a speechwriters’ party with his knowledge of a teacher at the court of Henry VIII, who translated works that he thought were by Seneca but that are not. In the 1970s he had wanted such a character for a Tudor play.’

‘Politics and writing were all part of the same business, he used to say. It was the business of being human. Some of his theatrical friends used to snipe at his working for “that ghastly woman”. Some of his political friends looked down on him as a showman. Their shared error was one of Ronnie’s favourite themes.’

‘Sometimes he took her on theatre trips, for pleasure, not instruction, the pleasure for her, most of all, of being applauded as she took her seat, a response that took him risk and trouble to arrange. Margaret the performer must never become too theatrical: actors, as Seneca knew, were not trusted to tell the truth. But neither must she neglect the artifice of the stage: if she was not noticed she was nothing. Politics was an art irreducible to logic – and Ronnie was a modest master of it, telling me many things and teaching me more.’

Miss R turns a page in her book of roman numerals.