![]()

1.6.14

It is much easier to write about Margaret Thatcher now that she is dead. This is not because last year I might have libelled her. I would never knowingly have done that. The dead cannot be libelled (that is one of the first laws that a journalist learns) but my ease in talking and writing does not come from freedom under the law. It comes because her ghost has gone too. She was a ghost even while she was still alive, someone whom journalists and politicians began to understand less and novelists rather more. It is better not to look directly at a ghost. This office is full of novels that Miss R should read, English not Latin, modern stories by Beryl Bainbridge, Philip Hensher, Alan Hollinghurst and Ian McEwan, as well as those by Seneca and Petronius who were on the shelves first.

![]()

2.6.14

Miss R has not enjoyed her journey here today. I know this from the way she sighs and seizes the chair. She has come here not by car but on foot, avoiding the simplest route, varying her journey away from the clogged Highway to the path along the concrete banks of the canal. Searching for her notebook, chuntering to herself as much as to me, she complains of sweating roads, a jungle churchyard full of tropical birds, parakeets and budgerigars.

‘Are they escapers from a zoo, she asks, ‘or immigrants with nowhere else to go?’ This is not a good day for her white shoes.

I know exactly where she has been and why she might feel sick. She has visited the site of the Latin lessons. She has put off till today the task of seeing the pub where Frank and I declined nouns and conjugated verbs. She has pushed open a door into the most ponderous of Hawksmoor’s churches. She has found a Bangladeshi playgroup in the gloom. She has walked the side roads where Ronnie illegally parked his car. And finally she has looked through broken windows at the place where we learnt The Usefulness of Basic Principles, where David showed off his homework and Woodrow checked on our progress and the problems of I Claudius.

Sensibly, she did not stay there long. The roadside by The Old Rose is grassed and fetid now on even the best of days. The path down to the river will become even more disgusting until someone pulls a lever to put the canal water back. Maybe there is a leak, maybe the harbourmaster has lost his job. Whatever the cause of the drought each separate section of the Thames dock channel has suffered a separately shallow fate, the first part holding just enough cloudy river for a diamond drift of oil and leaves, the second dried and steaming, the third clear but toxic, the fourth full of floating blossom in a Petri dish of golden brown bubbles.

I walked this way myself last week. It ought to be a way to avoid the polluted Highway. Instead, the air smelt worse – of vomit and of dead birds, visitors and natives, afloat on green slime as flat as a snooker table. As soon as the canal was behind me, even the fumes of limousines heading to Canary Wharf came as relief, even the lorries the length of small trains heading to the east coast ports.

In 1987 The Old Rose was a haunt for drinkers, drunks and five Latin students. It is closed, planked and boarded now. it was the last survivor in what was once a string of pubs serving beer and petrol fumes, entertainments for Jack the Ripper’s victims, his tourist pursuers and the mistresses of J. M. W Turner, the “little fat painter”, as the locals knew him. Still standing, more or less, it is now the last survivor of the club that gives this book its name.

No one should take this canal route till the water returns. Perhaps that will happen when the newspapers are gone. Sometime I have seen school parties here, groups led by anxious teachers seeking a brick-and-water classroom aid, a reminder of Britain’s sometime supremacy at sea, the decades when this channel connected dock to dock in a chain of trade that stretched almost to the coast.

Sometimes the children are learning how to canoe.

![]()

4.6.14

‘How about Lord Wyatt’, says Miss R, her mouth suddenly a thin red line of exasperation. ‘Newspaper columnist, bookmaker, diarist, wine-snob, friend of rich and Royalty.’ She is speaking as though reading. She is leaning forward. ‘There is much to say.’

‘You could have asked me before. The most important fact to understand is that Woodrow was a master of flattery. Visit Churchill College, Cambridge, the last resting place she chose for her papers. Look at the obsequious letters from those offering help. At the height of her power Mrs Thatcher attracted devotion of the kind that is good for no one, hymns to her virtue that eventually deafened her to all good sense. But the prime flatterer’s role – in this highly competitive field – was the one that Woodrow Wyatt held.’

She scribbles in her book.

‘He didn’t hide it. He flaunted it. He used to boast how he telephoned to “cheer her up”, to tell her facts of her success that were “hidden from her by ministers”, to pronounce upon her natural virtues, to accept her gratitude for his laudatory columns, to say how good her own newspaper articles had been, articles that she had sometimes never even seen before Woodrow praised them.’

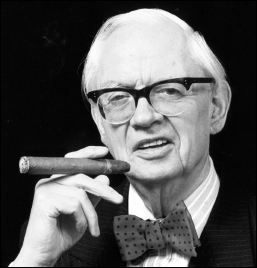

Woodrow Wyatt

‘Didn’t David and Ronnie do the same?’

‘David never came close enough to compete. Ronnie was a ruthless critic of Margaret by comparison with Woodrow’s Voice of Reason. Look in her archives for yourself. The longer that she remained in Downing Street the more dependent on nonsense she became.’

Miss R signals for me to stop. ‘Go back a bit’, she says. ‘Start at the beginning, always at the beginning.’

I’m going to make us both more comfortable. I point to a small padded sofa by the door, too old for the new offices, about to be abandoned in the move. I should help her but she does not wait to be helped. It is light enough for her to grasp it with one hand, a surprisingly strong right hand, to drag it across the paper stepping stones. She draws her arm across the view as though she were pulling aside a curtain. For the first time we sit down together, looking together down the cobbled road.

‘Woodrow and I were never close’, I begin – in preemptive defence of my failing to help her with whatever history faculty question she is working to answer.

‘You say you are interested in David Hart, Ronnie Millar, Frank Johnson and Woodrow Wyatt? Well, Woodrow and I spent the least time together of all the four men on your list. He was the most difficult. When he was alive we shouted at each other as much as we spoke.’

From the new comfort of the sofa I point out some of the places where we used to shout, the collapsing upper floors, the barricaded doorways, the mangy plots of lawn behind the gates.

‘That was then and this is now’, she says, moving away from me along the seat where there is little room to move. ‘My job is just to find part of the picture. There are people working on this all over the place.’

I don’t fully understand her. ‘What picture?’

She does not want to answer and looks as though she would prefer to take back what she has said.

I still feel mildly confused. I should be sharper to talk about Woodrow, the man who will be at the heart of one of the strangest Senecan stories. Miss R almost relaxes as I begin with what was once well known but is not known so widely now.

‘Lord Wyatt of Weeford, as Mrs Thatcher later entitled him to be known, was a man of frail appearance, strong opinion, moderate skill in many things and magnificence at flattering the powerful. In 1984, when I met him first, he was already a veteran moth at the flame of British power, a famous host who poured out fine wines and fierce words, most of them in the cause of his friends. I saw him then as a populist snob, a proud man who prided himself on knowing the People’s opinion. He considered me to be a non-populist snob, much the worse kind.’

‘But you worked together for years’, says Miss R, for the first time seemingly surprised by my answer.

‘Yes, we needed to work together’, I tell her. ‘That did not mean that either of us wanted to.’

‘Yes, he worked for The Times and he had his weekly column in the News of the World. But he exercised his zealotry in the cause of characters who ranged rather narrowly, I thought, from Margaret Thatcher to the Queen Mother.’

‘Although he brought fun into a room, he brought trouble too. He was loyal, which was a virtue of a kind, except when he sat at night with a dictating machine in his hand. Many were the friends who thought him loyal until they read his diaries after his death. He was generous with his gifts, particularly to anyone who could help him in return or with whom he had shared his childhood. His “Voice of Reason” was a title held with a wide smile without irony.’

Miss R circles her hand towards her body, her way of saying that I should start further back.

‘So, yes, when he first invited me to lunch it was to abuse me as “a naive intellectual” and to use me in some way if he could. That is what he told me later. He wanted to talk about short stories and plays, his own in particular, the virtues of Robert Graves’s I Claudius and the possibility of his writing a novel himself, maybe on a Roman theme.

‘Did he mention any other Senecans?’

‘He told me that David Hart was a maniac, a security risk, more libertine than libertarian but somehow influential on Margaret. When he spoke about Ronnie, he used the term “hired hand” – even though Ronnie was never hired, never paid anything for his speeches, and Woodrow himself was always desperate to be paid. We drank wine of which he was volubly proud. His diary recorded the name.’

‘And about Frank Johnson?’

‘Woodrow thought that all wit was dangerous around Margaret Thatcher, but that Frank’s wit, being the subtlest, was some of the safest. She did not always understand it.’

Miss R looks unimpressed. Is that all?

‘I could tell you much more about Woodrow Wyatt’, I say, ‘but not from the first time we met. The first time we talked (I was alert now to all her distinctions of seeing, talking, sharing food) was on the Belgrano day when he delivered the identical ‘scholarship’ message to me that David and Ronnie did.’

‘You should have mentioned that before’, she complains, more like an interrogator than a historian.

‘I don’t think so. Woodrow was less directly concerned with me that day than were the other three. He aimed always at the highest point in any social or editorial pyramid – and that was not me on that day, nor on many others either.’

‘There were many later lunches, like the one at which he used Kingsley Amis to stop me trying to reduce his contributions to The Times; or the many times when he abused me for reporting the “madness” of John Major on Black Wednesday; and when he invaded my office with Frank Johnson on the way to a News of the World party and put his finger through an oil painting.’

I expect Miss R to ask for more about that Black Wednesday, September 16th, 1992. It was a well-known date once, when suddenly an economic policy collapsed, when speculators spread the political reputation of a Prime Minister across their trading room floors. It is one of her subjects, possibly her main subject. Instead she stares through the glass walls of the TLS, imagining some impossible past in which oil paint might have surrounded us instead.

‘Was Woodrow Wyatt, the News of the World’s Voice of Reason and dinner host to a Queen and Prime Ministers, a regular wrecker of art?’

‘No’, I say. From a sharp angle I can see her own face in the glass, querulous and broken into parts by the remains of transparent tape which, till yesterday, supported a calendar.

‘Woodrow was a connoisseur. He knew about paintings, particularly those by his ancestors. That was the day when he tried to show off his knowledge of the dull brown portrait of an artist at his easel that hung behind my office door. It was a ‘novelty item’, he said, that had entered the Times art collection only because its subject, a pseudonymous Jacob Omnium, who also used the name Belgravian Mother, was a once renowned writer of Letters to the Editor.’

‘“The small black dog playing around its master’s shoes”, he added proudly, “was from the brush of the lion-maker of Trafalgar Square, Sir Edwin Landseer”. Woodrow was still explaining this to Frank, as though to a moderately damaged child, when he touched the creature’s tail and a large patch of brown paint and varnish fell into his hand.’

Miss R smiles into the smeared mirror.

‘Frank Johnson was a wary friend to Woodrow as was I. On that picture-punching afternoon Frank stood beside us like a don about to enter a brothel, sardonic, contained, certain that he should not be on his way to the News of the World party but looking forward to “the copy” for his diary he might get from the night.’

‘As the tail pieces fell to the carpet he bounced up as though he were about to dance and smiled at me as though he had planned the embarrassment himself. Frank was impressed neither by Woodrow’s art conservation nor his art history, not at all when he noticed the little plaque at the bottom of the six foot picture that clearly identified Landseer’s sausage dog.’

‘As the tour continued, Frank smiled kindly only on the faces of Henri Blowitz and William Howard Russell, reporter heroes of the second half of the nineteenth century, the first fortunate enough to have been painted by the fashionable Frenchman, famous portrayer of Hamlet and Queen Victoria, Benjamin Constant, the second by a hack who made a decent job only of the Crimean tent.’

‘Both men pointed to the only female figure on the walls – and in the whole Times collection – a woman who had married a former proprietor, lived with him for a year and then died. Beside her was a peculiarly beautiful lily, with, in this case, no indication that the flower had come from a superior artistic hand. Frank smiled again. Woodrow scowled.’

Miss R is making me nostalgic, normally what she wants to avoid. Or maybe it is the looming sense here of departure and destruction.

‘These paintings were what everyone expected at The Times when I was there – antique, imposing. My walls themselves, however, were not at all what visitors to the newspaper imagined. They were low and windowless, their proportions liable to oppress even a captain of submarines and to delight only an interrogator of evil intent.’

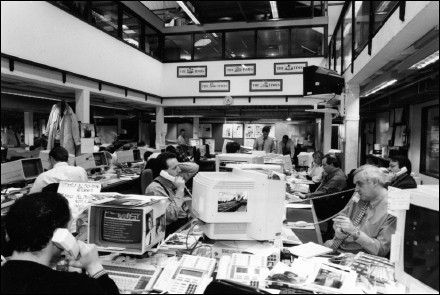

‘When the journalists of The Times arrived at Wapping in 1986 our place of work was that long tube of brick that you can still see, corrugated-iron roofed, beside the main plant. At the far end, where the cartoonists sat to catch the light, there is the wide door for Charles Douglas-Home’s wheelchair, the door that he did not live long enough to need.’

‘In the then new red brick offices there was room only for machines, managers and the journalists of the News of the World and the Sun. So our home became this so-called Wapping Rum Store, built, it was said, by prisoners of Napoleon’s wars in grey and yellow brick and apparently set to survive now again, as expensive shops for the expensive flats when the latest Wapping revolution is complete.’

Beneath the mezzanine

‘No new window in this brick was then allowed. Before we moved to the London docks in 1986, few had even known of the Rum Store – and none had cared. But architectural conservationists became rapidly romantic. Some of those who sympathised with the print union protesters found it easier perhaps (and more soothing for their guilt) to put up small obstacles to our business than large ones.’

‘Perhaps the “rare French brickmanship” around us was indeed a masterpiece. Whatever the reason, all queries about whether a hole might be punched in our office walls for natural light, or for any reason other than a wheelchair, were met with shrugs. It was as though I had walked the two hundred yards up river to the Tower of London and asked for a white plastic conservatory on William the Conqueror’s White Tower.’

Miss R has had enough. This mention of King William is too much. She is getting anxious about her ‘chronology’. I have come to recognise when this happens. She fears a return to Thomas More. She wipes her face, complains about the dust in the air and studies her notebooks, the electronic pad first, then her SENECA.

![]()

6.6.14

Immediately below me I can see what will happen next. The last parts to be built are the first parts set to go, the glass tower of lifts and gardens and atria that grew from the western side only when it was safe for there to be glass on the plant at all. In 1986 there was only brick. Any panes then would have tempted bars and ball-bearings from those opposing Margaret Thatcher, market capitalism, Marxist groups deemed traitors to the Marxist cause, scab journalists, scab electricians, scabs of every kind who were doing ‘print-workers’ jobs’. In minutes it will be glassless again.

Yellow cranes carry crashing balls of steel. There are grey concrete ramps where escalators once gleamed. Blocks of ceiling-lights, anonymous parcels of weight and black tape, hang down from cables like bodies brought down from a mountain. Fountains of water play on the pillars, no longer to create the illusion of calm but to prevent fire.

Miss R has a map and photographs. She prods and asks, asks and prods.

‘High under the roof is the dining room where we once entertained visitors and did not dare to invite Margaret Thatcher in February 1986.’

‘Go on.’

‘There would have been a riot outside if we had tried. She might have been tempted to come through the gates. She would surely have been advised against doing so. Some of us liked our lunching box in the sky. We wanted it to be seen. We thought about its redecoration. We thought what we might serve for lunch. And then we played host to her in the Mikado room of the Savoy Hotel. ‘Three little girls from school are we, ending our career with a touch of glee’, sang Frank, who loved opera, even The Mikado, and, as a schoolboy extra, had shared a stage with Maria Callas.’

‘I was the one sent ahead to check the place cards. Thus Margaret and her civil servant, who liked to be punctual, and I, who had my job to do, were beaten to the room only by a man with a Hoover who worked on till he had cleaned every corner. She seemed younger than at the sycophants’ lunch, more crisp, less motherly, less and better perfumed. We mused on whether patients should pay for bed and board in NHS hospitals and if not why not. We remembered Anthony Berry and his dogs.’

‘She had seen an excellent idea for advancing wider share ownership in Good Housekeeping magazine, “such a good guide to our culture” she told us when the lunch finally began. David had wanted me to mention his name at some point so that I could report to him her response, a warm and favourable reaction, he hoped.

Somehow the opportunity never came. I blamed the man with the Hoover.’

Miss R points at the black hole that, till five minutes ago, was our office dining room.

‘Beside what is left of where we ate is the last girder of the corridor where Woodrow once pushed me against a wall. I was sure he was going to hit me. This was soon after the Good Housekeeping and Hoover lunch. He was enraged that a Times political writer, in a formally arranged interview for Good Friday, had asked the Prime Minister about her personal shares, her dealings in those shares and whether sharedealing was something that prime ministers should do. “This was a disgrace”, he screamed. “None of her responses should be printed. It was a breach of an agreement made at the lunch”.’

‘Not the lunch I attended’, I said.

‘“Then it had to be another lunch”, he snarled back.’

The setting for the whole scene has been struck by steel now. For the first time Miss R is watching with clear attention. ‘What was that share business all about?’

I too am rapt by the wrecking balls. ‘At the beginning of 1986 even her most loyal courtiers were beginning to be concerned at what was then called “sleaze”, not yet a cliché. David saw “spivs” everywhere. Business supplicants saw David Hart and no less firmly held their noses. Ronnie feared that a little PR man, the same little man who wanted to share his elocution classes, was entwining Westland, Mark Thatcher, a knighthood for a tobacco boss and a request to sponsor a motor racing team.’

‘But Woodrow was furious at the calumnies. Surely we had not asked Margaret about such nonsense? She was quite right to ask that, if she did not like the interview, we should not publish it.’

‘I told him that I didn’t understand. An interview was a theatre show for her. She had to be calm and she, if not he, surely would be.’

‘Woodrow retorted that she had “quite enough real enemies” without my becoming one, “friends of yours”, he sneered, John Mortimer and Antonia Fraser who were modelling their plots against her on the plots against Hitler. She needed protection. Our interview was intended to be about “popular capitalism”, the “way ahead”, “trade union intimidation at Wapping”, “the ‘next big challenges”, more specifically, if that was strictly necessary, about the future of British car production, the question of whether patriotic customers might buy more Land Rovers if the Land Rover company remained in British ownership.’

‘This last unlikely theme, I guessed, was one proposed to her by Woodrow himself. He did not hit me but he did hold my jacket and push my shoulders hard against the plaster. The government has not “lost its strength”, he said. It is not “accident-prone”. Margaret will “without equivocation lead the Conservative Party into the next election”.’

‘That wall cannot have felt the like until the iron ball that has just now crashed it into sky. I told David what had happened, hoping for some sympathy. He said that Woodrow was absolutely right; that The Times was “out of control”; that the Editor and I were not sufficiently loyal to Margaret; that Frank was furious with me; that, if we were not more careful, it would be time for the “Colonel and the Wild Beast” to take over. When David was angry he often spoke in code. He never seemed to mind when this stopped him being understood.’

Miss R has been listening with an ever more puzzled look. ‘I thought that you did support Margaret Thatcher in those days?’

‘ Yes and no. The Times was in a difficult position. Whatever the Editor, Charles Wilson, and I, his deputy, thought of her and her policies, at least half of our readers hated both. Unhappy readers were always liable to defect to other newspapers that made them happier. Defecting readers meant lost money. Too much lost money might mean lost editors.’

‘Where did we stand? We drew a triangle with a long horizontal base to mean support, a shorter upright to show attack and an acute line between them. We stood on that “acute”.’

Miss R gives a sly look of understanding. She taps her SENECA notebook. She wants me back with Lord Wyatt.

‘Any attack on Thatcher at all’, I tell her, ‘made Woodrow angry. Fortunately for both of us, he could never remain angry for long.’

‘When he invited me for lunch at his house the second time, a few months later, he had more important anxieties than the Prime Minister’s Australian mining portfolio, and why it had taken six years of power to put it out of her personal control, or about promises to ennoble sponsors of racing teams. He again feared that I would try to remove him from The Times.’

‘Woodrow was right about that. I still did not like his unswerving support for his dinner party guests. I still did not appreciate his weekly claim to Reason. He thought that if I ever had a chance I would probably “kill” his contributions (killing being the verb of choice for removing unwanted articles from newspapers). He was right about that too. Those were impeccable reasons for a lunch.’

‘That was the day he invited Kingsley Amis too, one of Woodrow’s many friends who had made the meandering journey from left to right over their years. When I arrived Amis was already there, seething quietly in a tweed jacket beside a table on which his Booker Prize-winner, The Old Devils, sat. Woodrow told him that this study of sexual rivalry among Welsh pensioners was a masterpiece. Woodrow was ever adept at praising those who did not need more praise. He thought I needed extra lessons in that art.’

‘Our main topic was to be money. Amis was to be his support. Woodrow was never as wealthy as he liked to seem. Difficult marital unions as well as the industrial sort had seen to that. His difficulties were real and freely confessed, albeit of the kind, he said, that could not possibly last. Unlike David, Woodrow was without codes. He was direct. Few ever misunderstood him.’

‘Woodrow was confident, enthrallingly so as it seemed to me in our good times. He had been briefly rich in the past. He had owned his own small newspaper which he would have liked to be a large one. He once wrote a short story about a get-rich-quick scheme and published it himself as if to make the fiction true.’

‘He always liked to live as though he were inevitably (and soon) about to be wealthy again, about gently to rejoin his school friends, racing friends and royal friends in worry-free consumption – in his own case in the cause of the public good. As for the present, the money from his column in The Times mattered to him a good deal. He was keen that I properly understood this tiresome but temporary problem.’

‘As other guests arrived there was a brief diversion. The subject was the appropriateness at dinner parties of serving good wine at one end of the table and bad wine at the other. Woodrow said he did this all the time. It was fortunate, he said, that young people normally preferred to sit together even if it meant that their champagne was from Sainsbury’s.’

‘Amis said that the practice was fine as long as one’s own position at table was guaranteed at the good end. I said something haltingly about the dinner of Trimalchio and how the satirist, Juvenal, had howled when the rich of Rome tried this trick on their guests. Amis mentioned an awkward incident with an Arab ambassador. I said nothing. Instead I watched our host pour pale wine from old bottles, and listened as he asked if Juvenal and Petronius had parts in I Claudius. He did not recall them there “creeping and poisoning about” but those were the Romans that he liked best.’

Woodrow was a latecomer when we began our Latin lessons at The Old Rose. But he successfully annoyed Frank with the amount he could remember from his schooldays. And he loved Robert Graves. A Roman bestseller, packed with parallels between then and now, was one of the kinds of novels he most wanted to write.’

‘Which Roman “enemy within” was most like Margaret’s “enemy within” and would-be successor, Michael Heseltine? Which bore was most like her early supporter and estranged foe, Sir Geoffrey Howe?’

‘Before I could stumble to an answer, Amis quoted the appropriate wine lines from Juvenal – which made me wish that I had never raised the subject in the first place. Woodrow assured us that we were not to be drinking Sainsbury’s champagne any time soon. Amis grasped nervously at his glass of Scotch and we went in to lunch. This menu too would be committed to his diary.’

‘Afterwards Amis signed the copy of his book on the library table. Woodrow smiled and praised the sagacity of the Booker judges. He was as keen a collector of books as I was, one of our earliest bonds. Most of the recent winners, he said, were rubbish. In the year before The Old Devils the substantial cash prize, satisfyingly free of tax, had gone to a book about a deaf-and-dumb Aboriginal: the money had been collected by a women’s collective, a conga of Maoris creeping around the dinner tables. It had been a fiasco. He thought the prize would never survive it.’

‘And then, why had his friend, the black-haired beauty, Beryl Bainbridge, never won? Maybe “beauty” was not quite the right word for Beryl. She had a simian appeal at best, he said, but sexy, certainly sexy. She also wrote very good books, though not as very good as Kingsley’s, of course. She was a fine painter in oils and charcoal. She was from Liverpool, via Camden, and a “general good thing”.’

‘As I left to return to the office, Woodrow put the signed copy into my hand. I looked surprised. I was surprised – and pleased. The black-ink inscription read “Jolly good lunch and cheers to old Peter, Kingsley Chez WW, 1986”. This was the first, but not the last, time that I was ‘Woodrowed’.’

‘Woodrow mentions in his diary of this lunch Amis’s admission of having given up sex. I did not hear that myself. He also notes the 1964 Cos Labory and the Graves Royal 1947, wines that I drank without discrimination. After that we became almost friends. I did not try to reduce his contributions again, or at least not for another eleven years.’

My ‘first edition’ of The Old Devils is now by Miss R’s feet. She stacks it carefully on one of her piles before getting up to leave.

She is going to miss the main show of destruction today. At Wapping this afternoon, Woodrow’s corridor has already gone. The floor half-carpeted in blue for the most senior managers has gone. The zone with the sign welcoming visitors to Sun Country has gone.

The grandest offices of all are to be crushed by the claws of the highest crane. A man in a blue overall points up to a place in the sky. I am trying to remember the pleasures I took there, the storytelling, the hunts for stories, the successes, the wit and wisdom of friends. Instead I am seeing all the aggrieved subjects of newspapers in the past thirty years who would love to be driving that smash-and-grab machine, would probably pay to be driving it.

‘Just think, Miss R, of all the people who hate the newspapers that were in those offices, sometimes with a reason, often with none.’

She stops. Perhaps for once she is following me rather than leading. She seems keen to leave as fast as she can.

‘Think of the pickets of 1986, the Tories too fond of schoolgirls, the celebrities with mobile phones, the “scroungers”, the Prince of Wales (for reasons, architectural, political and personal), that Karmic football manager, that other football manager whose face was turned into a turnip, the doctors in bed with their patients, the Cabinet ministers who did not have sex in football kit or keep a Miss Whiplash in their basement.’

I cannot remember all their names. All I can see of Miss R now is the back of her tight belted coat as she leaves the room, just like one my mother once had. I am even remembering the rock star who did not surgically silence his guard dogs, who sued, and won a grand apology. I am thinking on and on, of worse and worse, because bringing back bad memories is what the dying of a building, like the dying of a person, seems to do.

![]()

12.6.14

‘Margaret Thatcher was not one of those who hated newspapers, not in her high days in power anyway. The Daily Telegraph was her paper of habit and the Daily Mail was a reliable supporter. She also once mentioned to me her reading of Today, a “plucky newcomer in the middle of the market”. This paper, now dead, was edited briefly at Wapping at the time by the fierce Labour Party supporter, Richard Stott, a master of editorial disguise, author of Dogs and Lampposts, soon to be available again in a nearby Oxfam shop.

From the rest of the press her courtiers aimed to manage her moods, ensuring that she should read only the parts that she would like. Columns by Frank Johnson were often in her cuttings file. She best enjoyed sketches that compared her to something conquering and stately, a galleon perhaps or a giant gun.’

Miss R looks surprised. ‘Did she have a sense of humour?’

‘No, she often failed to see Frank’s jokes, but laughter was not what she was looking for. She was not even unusual in that. Most Members of Parliament liked to be sketched by Frank. Unlike a cartoonist he did not exaggerate their thick necks and noses. Any minister who had made a speech might find himself the butt of an extended parody but this was at least some proof that the speech had been made. Even The Times had stopped recording speeches in any other way.’

‘When did you and Frank Johnson first meet?’

This time I snap back at her. A greater variety of approach would be good.

‘Rather than keep asking the same questions, you might do better reading what Frank wrote about Margaret Thatcher herself. He is still a good guide to how she wanted to be seen – as confident, motherly, harder working and farther seeing than the rest of her kind.’

She asks her question again. She has her list and she will not be deviated. She is comfortable and has adopted the two-seater sofa for her own.

So when was it? She has made a strange game for us but I am in it now. I must not be caught out. Frank and I must have ‘brushed by’ one another often after 1978 but when did we first ‘meet’?

I take a longer pause. ‘The date that Frank and I sparred our opening rounds, shadow boxing, the role we came to occupy for the rest of his life, was probably in 1985. I remember the scene if not the precise date. It was another mark in that crowded year before we moved to Wapping, when newspaper revolution was in the air for those keen to sniff it, even if the exact form that it might take was known to very few.’

She makes a note on her SENECA pad.

‘We were both looking out over a different London skyscape at the time, one just as little known to me in detail as the one we are looking out at now.’

‘No, I am not proud. Everyone should know the names of the landmarks outside their windows. It is only polite to be able to do so, to make visitors feel at home or at least to feel that they are with a host who is at home.’

She looks around the piles of personal and professional relics, the two types indistinguishable among the removal piles.

‘We were at a party on the roof of what “in 1929 had been the tallest office block in London, 55 Broadway, headquarters of London Transport, a masterpiece of Art Deco, all grey limestone and Murano glass with a statue of the West Wind by Henry Moore”. But it required Frank’s companion to tell me that.’

‘Who?’

‘Well, at least he seemed to be Frank’s companion. I knew Frank then only as the wittiest journalist to have ever worked in parliament (thus almost never in the offices of The Times) and as our present Bonn correspondent (posted temporarily abroad at his own request on an assignment for self-improvement). The authority on Murano and Henry Moore turned out instead to be the companion of our party host.’

‘It was a summer night and this very learned visitor from Canada was here looking to “buy properties”. He leant against the roof-garden wall and looked like a pile of gift boxes, battered but expensive cubes loosely tied with string, his square face scouring the skyline ten degrees at a time, naming, turning, naming, turning, naming, turning until he saw the Houses of Parliament where he stopped.’

Miss R turns her own eyes too. So do I. We each embarrass the other.

‘The visitor was challenging Frank or me or anyone to say Big Ben, to embarrass ourselves by naming something so obvious. No one was so foolish as to speak so, in the next ten minutes, Mr Black, who had dressed for the night in the darkest shades of brown, had identified every office, church and tower block that we could see.’

‘It was as though he were responding to questions that he alone had heard. Over there was the glass tower of New Scotland Yard.’

With no sign of thinking Miss R signals student dissatisfaction at a mention of the police.

‘And then there was Falkland House, home base for our watery colony, the Equal Opportunities Commission, from whose clutches all had to be saved, or so said Frank. Mr Black (‘Conrad’ as we were to call him) agreed.’

‘It was thought that this distinguished visitor might soon own the Daily Telegraph, where Frank was once a star. So there was a small crowd around him, individuals trying hard not to be a crowd, who listened as he spoke, laughed at what they hoped was a joke, and worried that the visitor might ask one of them a question about their home city that he could not, or chose not to, answer himself.’

‘The head of London Transport, Keith Bright, an equally polymath businessman, had to parry the most dangerous thrusts. He was the only man I knew in London life who had also known my father as a laboratory colleague in Essex. I very much wished Max Stothard had been with us on the rooftop that night. The two men shared Marconi sports days. We talked about those, the cream cricket flannels, the distinction between engineers and technicians, between the cakes (good) and the sandwiches (poor) which we took at tea.’

‘After fifteen further minutes on top of the capital’s most artful underground station, Frank was firmly in charge of the senior conversation, saying that Henry Moore’s “West Wind” was the finest work on the building but that Jacob Epstein’s “Day” might have come close had it not lost an inch-and-a-half of penis to the censors.’

‘“And what do you think happened to the rest of the penis?” Frank smiled his question. Conrad Black laughed. There was even louder laughter from his circle of listeners. After that Frank and I noticed each other more and more, warily at first, testing each other like boxers, trading insider gossip to impress where we could. He said that he was keeping a diary where one day all would be revealed.’

Miss R is taking lengthy notes now. Occasionally she looks out east where we first looked when she first arrived. There will be no good for her today in playing the Conrad Black game and asking what buildings we can see. Yes, I have worked in this sliver of riverside land for almost thirty years. I ought to know. But most of the time I was in that thin brick warehouse down on the ground. And, even in the best of circumstances, I can understand geography only if I do it as though for an exam. In today, out tomorrow.

As for this particular spot, I am a newcomer. I have been in here, up here, overlooking the Wapping plant site, on the sixth floor of Thomas More Square, for barely more than a year. There has been no time to change the spatial incuriosity of a whole life.

Next month everyone in the TLS, The Times, the Sunday Times and the Sun newspapers is moving west a little, to a new home beside London Bridge Underground Station. One of the titles that came here is missing. Woodrow’s old home at the News of the World has disappeared in recent scandals which, as she quietly makes clear, stand outside Miss R’s period of study.

‘Nothing after 1997 please’, she says, clinging to her calendar.

Outside this window the rubble is piling. The gatehouse has gone. Yellow-jacketed men pick over the flat remains like scavengers on a toxic copper mine, gingerly turning over the relics of security gone by. A small crane eats the few pieces of metal and plastic worth placing in its mouth. The next occupant of this office will not care what was there before. There used to be a grey-box bridge across the cobbles, like a sea-container washed up after a storm. I wonder what happened to that. No one will need to explain this place to visitors, not ever again.

‘And no, Miss R, don’t test me. No, we cannot see the execution grounds where More and so many others met their ends, not unless we go to the other side and look out west towards the underground at Tower Hill. We can see some Hawksmoor churches and their graveyards for exotic trees and birds.’

She makes a querying note.

‘Any grotesque church around here is quite likely to be by Hawksmoor and, unless you are unlucky enough to meet a polymath like Lord Black (O yes, he occupied his newspaper property, and his peerage, before spending a little time in an American gaol), you can reasonably safely pretend.’

‘Look instead at the Highway as it stretches out to the east, the Ratcliff Highway of the old marching songs. Watch for the dry-docked sailing ships that were once supposed to entertain shoppers at Tobacco Dock. There is no point in going back too far (thirty years are enough for me) nor going too far away. Most of what you seem to need happened in the hundred yards I can see without straining or thinking. The Senecans can properly be bade goodbye from here. It is too late to learn the names of the tower blocks now.’