![]()

5.8.14

We are not long now for this place. A hot, grey day is keen to bid us all the more swiftly goodbye. Sweating clouds squat above the men in yellow who are doubling the thickness of the grey steel fence down below. It is as though they too, like Miss R and I, are back in the Thatcher years.

On the side of the plant the red steel gallery that once looked down on Advertising Sales is ever more sharply exposed. The cream atrium roof above it is spattered blacker. Soon, like a pleasure balloon or hang-glider, it must all soar away with the birds.

Yes, all the birds. When Miss R first mentioned that she’d seen budgerigars and parakeets in the churchyard I thought she was exaggerating from ill temper with the heat. She was not. From what I saw there this morning she was understating the invasion, underestimating the escape. Singly, and in groups, there are dozens of parrots in the trees above the graves, not all small, some of them of proper value to a zoo or pet-shop, I would guess, vivid examples of creatures who live wild even in captivity, and when free shout ‘pay attention, pay attention’ while not wanting any attention to be paid.

Only an expert (or more likely a fraud) would say precisely what types of parrots they are. Psitticids, as Mr V used to say with learned realism, have ordered their parrot family very little over the millennia, sometimes troubling to differentiate their males from their females, their young from their old, their individuality over that of another, but mostly not. Birds of every sex and size wear the same black-and-yellow or white-and-blue, like families in their favourite football club strip. For once I wish that he was here, just to see them.

Or to hear them. From every group comes a uniform cracking of che-chek, che-chek, che-che or ruh-ruh-rah, killing the efforts of any bird with pretensions to sing its own song. A scarlet-rumped parakeet, one of Mr V’s favourites and one of those very few parrots that can hold a tune, would have no chance in competition against these black-fronted, green-bellied, ring-necked screamers.

There is no space for the birds that once flattered Roman lovers in Indian dialects and Greek. This is an urban mob in urban skies over urban trees. The higher shit on the lower. That is just the way it is in this air today full of noises.

Meanwhile on the ground below, the crows are wise and stately, ruffed and gowned, deep-thinking that with effort and patience they might become ravens of the Tower. They stare at the workmen and the workmen stare back – for hours on end if they wish.

Where is Lord Wyatt when I need him? Woodrow would have appreciated these hot and hopeless black wings. He would have had pink silk around his neck and pink champagne in his hand. He liked to see himself as something of an ornithologist. He always liked both to look at birds here and to bait protesters, baiting protesters perhaps the more so.

Even up here on the sixth floor there are green wings beating beyond the glass. The heat drives the parrots either to high windows or the shade of churchyard shrubs. The temperature is not what even a tropical bird is used to in England. It has, however, improved the mood for me and Miss R.

A call comes from Reception. She has returned. I was wondering if she would not. Four months after her first arrival, there is still space for misunderstandings. I know little about her work. I don’t ask her enough. I am too content to be asked. Sometimes I feel I am being interviewed by a pedant historian, at other times facing an analyst, a doctor, a casting agent, or a patient.

When she walks through the door I am assembling boxes for the books I used to care about the most, not those on the Seneca shelves but novels most of them. Miss R again offers to help. She is not dressed for removals. She is wearing a pink silk suit with short skirt and jacket. She looks as though she is on her way to the last garden party of the season. Instead she makes and stacks boxes.

‘You must have been mad to keep all these’, she says.

‘It was a long time ago.’

Together we skim across the paper surfaces, scraping dust onto our thumbs, finding evidence of me and against me, the price-tagged reminders, embarrassments now, of the three decades in which I suffered from a book-collecting disease.

She opens each title page and checks for dates.

She is looking for books from 1992, she says, ‘the next year on my list’, the year that John Major had his much alleged ‘breakdown’, Ian McEwan, Black Dogs, Proof, Mint (£275); Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient, First Edition, Fine (£110); Barry Unsworth, Sacred Hunger, Edited Typescript, Slightly Foxed (£400).’

I remember well both the books and the ‘breakdown’. ‘This was a year when Margaret Thatcher’s successor won an election and lost his power just as she had done. It was becoming a pattern. The Booker Prize judges were as indecisive as the new Prime Minister. There was a tie between Unsworth and Ondaatje. Indecision has been banned at the Booker since then.’

‘My mother is mad about books’, she interrupts. ‘Hers are like useless antiques, like all that brown polished furniture you see in country shops that no one wants. Yours are not even all read. You must have been even madder.’

‘Mine was only ever a modest mania’ I protest. ‘I did not see myself as abnormal, no more abnormal than is a collector of stories about politicians.’

‘Yes, I kept books that I rarely read, never read. You are right about that. I kept catalogues of words and kept them dead in cabinets, their covers “mint”, which means perfect, “fine”, which means as perfect as any healthy eye can see, or “good”, which means good enough only for reading.’

‘No, it never struck me as odd. Reading is very bad for dead books. It reduces their value and risks bringing them to life. It was a while before I recognised that this might be a disease.’

‘Exactly when?’, she asks.

‘Only around the turn of the millennium, long after the time we’ve been talking about. By then I was both Editor of The Times and seriously ill. There was a question whether one anomalous condition would die before the patient died of another. By 2001 I had survived my peculiar case of cancer but the bibliomania died and stayed dead.’

‘All that is left now are some 10,000 novels divided between wherever I have shelves. I cannot pretend that I have read them all. No, that is not true. I can pretend. I have often pretended.’

Miss R picks up again her grey-black copy of Winter Garden.

‘And look at these too. As though to please Woodrow’s ghost, I have a full set of Beryl Bainbridge’s novels, from two editions of A Weekend With Claude (1967 and 1981) to According to Queeney (2001) whose beginning is a picture of a corpse, Dr Johnson’s, whose corporeal legacy, I see now, includes withered kidney testicles bubbling with cysts and a varicose spermatic vein.’’

‘I was supposed to have stopped collecting by 2001 but Beryl must have been an exception. I have even The Girl in the Polka Dot Dress (2011), her novel about the assassination of Robert Kennedy which she left unfinished when she died. Another thirty days for thirty pages, she said, and it would have been done.’

‘And look at this one.’

She is friendly today and she does look.

‘A full set of the Australian double Booker winner, Peter Carey, including the short stories (1981), published in aluminium foil, the first Faber cover, its publisher once said to me, in which you could cook a chicken. Somewhere there is Ian McEwan’s Amsterdam (1998), about the mind of an editor of a newspaper.’

Miss R puts this one in her pile.

‘See. David Storey’s golden Saville (1976) sits six volumes away from the far superior blue-brown Flight Into Camden (1960), once one of my favourite of all novels. I used to think that I had, in a certain sense, flown into Camden myself, from Nottinghamshire via Essex, Oxford and Islington. But I would hate to think I liked the book for no better reason than that.’

She is patient with my collector’s enthusiasm, often so irritating to others, and surveys the different sections on the shelves. Between A-for-Atwood and B-for-Bainbridge, R-for-Rushdie and S-for-Storey are assorted other relics, a balsa car and radar dish, a nineteenth century guide to Rome, a set of postcards of parrots, all examined surprisingly slowly as she puts them away, nothing that anyone else would want to keep.

‘The books were a collection that I once thought might last. I afterwards ceased to think so. In the year 2000, when the doctors said that my last living months were close, I took some time to arrange each one in alphabetical order, each with an Ex Libris bookplate showing a seabird, a little tern, with a copy of The Times in its mouth.’

‘From a collector’s interest this was an act of lunacy, a systematic removal of “mint” status with every sticky label. Even for someone wanting to leave something behind it was a feeble gesture but, at the time, that was the only kind I could make. I still have the books. The only difference is that I have stopped adding to them. The bodily disease killed the mental obsession even as it let the body escape.’

‘So, you are still a collector?’, Miss R asks. ‘Everything is electronic. Even my mother has stopped now.’

‘No, but not because of what is electronic. It’s just the absence of a sickness. Look at these. Never again since the year 2000 have I formed the words Watership Down (Rex Collings, 1st Edition, 1972, in paper-bag brown dust jacket; £1500) or The Rachel Papers (1st Edition, signed, 1973; slight tear to end papers; £350).’

‘While I was a Senecan I collected like a miniature emperor, ordering for the brief thrill of the order, not always even opening the parcels. Whenever I tired of politicians and their courts (and even more with why I cared about them) I would pick out some Ben Okri or a bit of Julian Barnes.’

‘I would maybe read a few pages, sometimes even finish a novel in a fierce defiance of dullness. Then suddenly the need was gone. Two years after I escaped cancer I left The Times too. I joined the TLS. My office was suddenly empty of politics and filled and refilled with what I wanted to be within it. And now it is time for a new office.’

‘Have these books been worth their space?’

‘See this. In his essay On Tranquillity of the Mind, Seneca offers to a friend his top tips for mental peace: disregard riches, control all passions and restrict one’s book list to a few classic texts. Whenever Seneca begins such an argument he is about to lay himself open to some of the most damning counter-charges later made against him, excessive wealth, sexual and other hypocrisies. But on book-collecting he is right.’

![]()

7.8.14

I thought maybe that Miss R had finished with the Senecans but she has not.

‘Tell me more about your mother’s books’, I ask, politely but clumsily, stumbling into where she does not want to go and easily keeps me at bay.

‘Are David Hart’s novels in the shelves?’, she asks. ‘Should I add them to my pile?’

She is most welcome to turn the pages of The Colonel (First Edition, good, 1983, £2) and Come To The Edge (First Edition, signed ‘with love’, mint, 1988, £1). She will be one of the few to have ever done so. Neither is a collector’s item to collectors of books.

‘In those Poll Tax months what happened to David Hart?’

‘He never wavered from his position that the Thatcher era was over. Ronnie and he still disagreed, merely agreeing to differ more quietly.’

‘There had been “eight good years”, David said, and the rest of her time would be only wreckage. He began to live more in the country and less in town. He was already looking to the future after his “best friend” had gone.’

‘But look at his books if you like. In Come To The Edge the owner of a great English house plots the founding of a Great England political party. The Conservatives are deeply infiltrated by Socialists. The landed and the landless are set to rise up against the mercenary middle class. In his fiction sat the seed of what he hoped would be the truth.’

‘And then as soon as Margaret Thatcher had fallen in 1990, he wanted her successor, John Major, to fall too. He had successfully predicted her end but had failed to see what would happen next.’

‘Chronology, chronology, chronology. You are moving too fast.’

‘There is not much dispute about Margaret Thatcher’s fall. ‘The riots against the Poll Tax simultaneously ruined her reputation for radicalism and for common sense. Geoffrey Howe, one of her once closest and dullest allies, condemned her in parliament. Michael Heseltine, the “Tarzan” who had been plotting against her since the Westland affair, made an open challenge. She treated none of them seriously enough. Within two weeks she was out and on her way to Dulwich, to that Barrat Home in which she did not stay for long.’

‘The victory in the race to replace her went to the plotter who seemed the least to be plotting. Ronnie’s friend, Geoffrey Tucker, genial Mr G, master of the plotters’ Chinese restaurant table in 1979, was the earliest to call me and predict that this would be John Major.’

‘David called unhappily with the same message well before it was a universally acknowledged truth. There was nothing, bar deceptive cunning, that David admired about the bank manager who was about to take the office of his heroine. Worst of all, the new Prime Minister’s advisers made clear, even before they took power, that they wanted nothing to do with David Hart, not even through back channels, not even in secret.’

‘Once John Major had caused a second surprise by winning an election in his own right in 1992, David retired still further to country life, plotting hopelessly from afar. Of the other Senecans, Woodrow slipped easily from helping Margaret to helping John, from an object of his devotion to a mere source of power. Ronnie did the same but with much more difficulty, arousing jealousy and anger in his Margaret that he found hard to bear. Frank and I merely returned to our work, I now as Editor of The Times, watching closely as the next phase of disintegration began.’

‘Every close watcher of the Conservative Party had the same problem at this time. Who was the one to follow? The answer should have been obvious. A Prime Minister has the power. But when Margaret Thatcher lost her starring part she never left the stage. Even two years on, every Tory who loved her thought her still the victim of a vicious stabbing. Every Tory who hated her found that hating their leader was still the best game they knew.’

![]()

8.8.14

Most of the books have now gone. All but a single chair has gone. Miss R has moved to the letters. She is sitting on the floor by the door and sifting through unbound paper. Her white shoes act as weights. She says she does not need me to talk. She needs to read. Some of what she is reading I know well. Other parts I do not.

The letters are all in the pile from Mr V. She holds one in which he boasted of his latest palaces of wood. She has another in which he showed his satisfaction when my father was dying. That was sixteen years ago. Mr V wrote that he was saddened but he was not a deceiving writer and he showed that he was not.

In other letters which Miss R now riffles through her hands, I learnt that he held my father responsible for his losing his job and his exile to Walton-on-the-Naze. He was not happy there. He liked to boast about Walton’s new fame as the home of the world’s oldest parrot, a fossil discovery from fifty million years ago, Palaeopsittacus Georgii, George’s Old Parrot, with its own fossilised seeds and nuts. He described how his balsa house stood once beneath ‘an avian sky, a sun-blocking mass of red, green, yellow, blue and shit’. But the glamour did not last.

One of the letters beneath Miss R’s left shoe is a full denunciation of my father. The reasoning is incomprehensible but the tone is not. Another is about Mrs Thatcher’s fate. In a third, from around the same time, Mr V says that he has ‘given up the balsa’. All remaining relics of Rome have gone. His old house and my old house have all gone under the knife. The price of new wood is now beyond his reach.

So, in 1998, when Max Stothard was dying, and when Mr V knew that he was dying, I was not surprised by the pleasure from Walton-on-the-Naze, well beyond the usual quiet relief of a survivor. None of what I read was new and it was all from a long time ago. It was my own response that surprised me more.

This was the first time I noticed how the dying of a person brings out memories so very different from a death. Mr V wrote abuse in my father’s final months that he would not have written when my father was dead. I, too, who loved my father, sat with him in the hospice and failed to focus on all that was his best, his easy pleasures, his tolerance, even his tested tolerance of Mr V, his modesty, his mass of brain, so much of it kept in reserve.

This was not what I expected. If ‘nil nisi bonum’ applies to the dead, how much more should it apply to those not yet quite dead. As soon as he was gone I was able to invoke the ‘nothing but good’ principle with ease, recall all his many virtues but when he was going I could not. I did the opposite.

While his nurses were carefully matching morphine to his pain I was thinking of what he had wasted of himself (I shudder at it now) and how he had done too little to understand my mother. I was remembering what Mr V had too fiercely said, almost agreeing with some of it: that Max Stothard was too fond of a quiet life, too content to get by, so lacking in imagination as to be almost wilfully bound to the here and now.

My father was wholly without rage, a true virtue for Stoics. But while he was dying I remembered the only time that I had ever seen him angry, the first time he said I should never see V or her father again, the time I disobeyed him and he hit me.

At the moment of his death I was not even thinking about him at all, but of a shirt I had seen in a shop window, and whether I had time to buy it before 5.30, the time when every shop in Chelmsford closed, the time that was never quite early enough for my father who loathed all shops, the thought of them even more than the reality. So when he drew his last breath my thoughts were on shopping, which I too hate, almost as much as he did.

And so it is today at the dying of a building. Miss R has not heard memories that my friends and colleagues would expect me to have. This is not what the memoir of an Editor is supposed to be, the kind of memoir that I could have written, of meetings with great men, of awards, successes, the kind that are spread over this office floor. Instead Miss R has heard different memories, the ones that she has asked for, worse ones, flattering to no one.

If the building were dead I might not be thinking of the plots of politicians and the sins of the press. I should be thinking of virtues and pleasures, scoops and scandals exposed, the friendships that were once within those walls, the triumphs, as we defined them for ourselves, the strategies hatched to sell more copies of The Times, the successes by which my own success was measured long ago.

Instead the plant has been dying and I have been describing to Miss R a band of squabbling ghosts, figures reduced to an H, an L, a T and a J. This morning there is a giant pipe, newly arrived on a pile of fibreglass and seed buds, like a tooth removed by dental engineering and cushioned on cotton wool. Beneath the high cranes there are low cranes, bobbing and bowing, dancing with the fire hoses.

![]()

11.8.14

I now have a firm date for leaving. I do not have much more time by this view of memories. Miss R has been sweating over my final boxes, making notes, checking letters and files. Damp and pink silk do not fit well. We have snapped at each other for no good reason.

Gradually she is forming her own books into labelled piles. In five shelves yet to be emptied in front of my TLS desk, are more than a hundred books we have not touched yet.

These are the not very literate reminders of the decades when I had only to type the letter T for the letters H.A.T.C.H.E.R to follow.

Here sit rows of memoirs by so many Tory men whom no one wants to remember now, coy titles about kitchen cabinets and Tarzan, nicknames that a man hated when he was famous but, when he entered the ghost world, was all that remained, thick books with ‘blue’ in their titles next to thin books, more thick than thin.

Miss R has rejected Michael Heseltine’s Life in the Jungle (2000); First Edition, mint, 50p. She has found by luck or best interviewer’s instinct probably the only one of these that is worth taking to the new office, the only one that has found a life beyond the graveyard, albeit a fictional life.

Its title is Dancing With Dogma (1992); First Edition, Good, £5. Its author was the late Sir Ian Gilmour, a member of Margaret Thatcher’s first Cabinet, disloyal to her in every role he held. Sir Ian was one of Woodrow’s least liked Conservatives, an elegant journalist, sometime owner and editor of The Spectator, rich, urbane, ever delighting in his role as ‘wettest of the wets’, bitterly disdainful of her Falklands policy except to the extent that ‘it would surely do for her what Suez had done for Eden’.

His memoir’s cover shows him dancing at a Tory seaside ball with a Prime Minister whom he despised – and it is this image that has made the book survive, printed throughout the pages of the novel beside it on my shelves like Brighton Pier through Brighton Rock. The novelist, Alan Hollinghurst, won the Booker Prize in 2004 for this finest piece of Thatcher fiction, The Line of Beauty, a beautiful line that stretched through politics, cocaine, critical theory and the contours of arse and AIDS, gripping the Thatcher age in ways that Miss R and her colleagues will struggle to match. Other historians have already struggled.

For understanding the years of The Senecans the best fiction is often better than the best journalism. The Line of Beauty begins after the Falklands victory when the ‘pale gilt image of the triumphant PM’ is everywhere. Her recapture of Port Stanley merits an annual public holiday and a reconsideration of how we feel now about Lord Nelson’s long dominance of the skyline.

A Reaganite lobbyist promotes Star Wars technology as David Hart used to do. The rich get rich and ‘the poor get … the Conservatives’, is the line that lightens a dinner party. Madam’s ‘genius’ can move any conversation away from reality – from fine food, fetid neighbours and a pied a terre that is better described as a ‘fuck-flat’.

There is subtle textual and sexual variance. The gay hero, an outsider at the court of ‘the Lady’, catches a dance with her that causes rage among those whose claim is greater but whose opportunism is less. It is one of the finest novels of our time for imitating its world.

Miss R hasn’t read it yet. She places it on the pile that she has asked to take away.

![]()

12.8.14

Over the past few days the lawn down below has changed colour in the heat – from brown to bright green to an even brighter yellow around its edge. Despite the efforts of Wapping’s chemical gardeners, the edge of our newspaper lawn was often nauseous yellow where it met the concrete. This will be its final season.

‘It reminds me of Cyril Lawn’, says Miss R.

‘Don’t you remember? That artificial turf of the 1960s. My grandfather still uses it. A bit yellow now.’

‘Yes, I do. My father laid it in the corridor that led to our garden, plastic tufts sold to him under the slogan “THIS IS LUXURY YOU CAN AFFORD BY CYRIL LORD”. To his horror and distress our Essex patch of Cyril Lord’s Cyril Lawn became yellow within days.’

We talk, idly but cautiously. She does not mind incidentals about colours and carpets unless she sees the conversation hardening around places where she does not want to go. I try to ask more about her ‘Thatcher project’ but she is as vague as a party-going spy.

She wants only to return to the Senecans. She wants to take them beyond 1990, beyond the Thatcher fall. We start to talk about 1992 but her mood is more sceptical than before. She says that she does not accept what I’m telling her. I object. She goes back to exterior floor-coverings. I complain again.

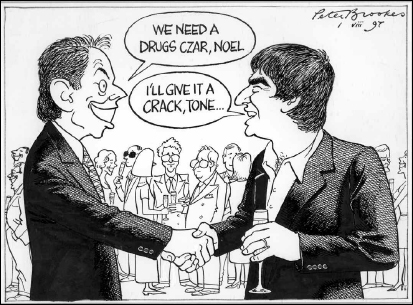

‘Listen’, I insist after half an hour of politics and soft pile, ‘it was definitely Woodrow who first told me about John Major’s “breakdown” on Black Wednesday.’

‘Black Wednesday was what September 16th,1992 was called. It was in Margaret’s successor’s sixth month as an elected occupant of Number Ten and my own first week as Editor of The Times.’

Miss R is crisp.

‘I am not disputing the name of the day’, she says, ‘only your account of who told you what happened on it.’

My account, I know, does not fit with those of others.

‘Believe me. Woodrow Wyatt was both the source of the “breakdown” story and the man who most vigorously denied the truth of his own account. He was also the man who most aggressively abused me for publishing it.’

She nods as though I am giving in to her view.

‘Yes, this makes your research more difficult. It does not make my memory unreliable or my statement untrue. Denial of the truth is by no means unusual to a newspaper editor. It goes with the territory, as my father used to say, talking of territory that was somewhat different.’

I have known since April that Miss R would at some time reach this point. She has her four subjects. She still identifies them in her notebook by the letters we saw in the smoke when the building first began to fall, H for Hart, T for Millar, J for Johnson, L for Wyatt.

She has learnt a little now – more Latin than she wants to learn – about what brought the Senecans together and what did not. Today she wants to talk about their part in the most difficult day of John Major’s time in office, the day, as The Times reported, that he disappeared from view, abandoned his desk, becoming lost to his courtiers, civil servants and to the world.

John Major himself has always denied this. His is the official story. Maybe it was never very important anyway. But what Miss R wants to know is where I first heard the opposite.

‘I’m telling you again that it was Woodrow who told the story first. The other Senecans played their part but Woodrow was the first.’

She shakes her head.

‘Woodrow did not mean to be my source. He did not even know that I was about to overhear him in his borrowed office, one of those that are now a black square against the sky, at a desk where he was speaking on the telephone, and where he was listening, mostly listening, to someone else.’

‘So, yes, all that I am saying is that Woodrow knew about the “breakdown”. He was talking to someone else about it. Woodrow would not mind my saying that. He would always want to be known for knowing. I was not meaning to overhear. Nor did I think at first that I had overheard anything very much.’

Miss R’s eyes say that she is going to have to report this explanation back to someone else, and that she too is not going to be believed.

‘At the time in question’, I say as though in court, ‘I hardly knew even where I was. But it was somewhere in the windowless middle of that vertical chess board, the part they are blasting away now with fire hoses and cranes, the part where I never normally went, the place where the advertising sellers used to sit. I was looking for my columnist in the offices of the News of the World, also somewhere I had never been before.’

Miss R says nothing.

‘If Woodrow had wanted to, he could have come to see me in my own office. That would have been more convenient. But he normally preferred not to come to The Times. He thought that my colleagues disliked him. They did.’

‘He and I needed to speak only briefly, about some “crass” editing of his column, the commonest reason for us to meet face-to-face, blue-marked proofs in our fists. I circled the blue-carpeted corridors where I thought he might be. There was no chance that he would be in the restaurant or at the hairdresser. Eventually I found him behind a door beside the red rail that ran around the atrium called Adland, the rail that is now that single spot of colour in the vertical squares of dust.’

‘He was talking on the telephone about the odds for a horse race. I waited and walked around the Adland corridor again, in a continuous square, back to where I had begun. He was still on the telephone.’

‘What I heard then seemed nothing at first. The clearest words were coat-hanger, vacuum, television and pillow. It could have been an order from a department store or the inventory of a holiday cottage. In its more mumbling themes the conversation covered “John’s terrible state”, the “heroic support” he was getting from a few of his very best friends and the incompetence of the Prime Minister’s office. None of this was much different from Woodrow’s usual tirades.’

‘Yet, as he went on, repeating, restating, turning the words around, the story was there, along with an anxiety in his voice, a slackening in his characteristic crisp twang. The Voice of Reason always spoke as he wrote, assuredly and with the aim of instilling assuredness in whoever was hearing or reading. This time there was a touch of fear.’

‘So yes, I heard the story more than once. And I heard it from Woodrow and from whomever he was talking to, a woman I am fairly sure. I did not wait outside any longer. I abandoned my mission to discuss his complaints. I walked away, around the red steel rails. Later he crossed the path into the Rum Store and came to see me at The Times. I mentioned nothing of what I had overheard.’

‘How much could you really tell from Lord Wyatt’s voice?’ Miss R is listening, languidly leaning against the door. Of the two of us she seems much the more at home.

She scribbles on her Seneca pad in symbols that must be some kind of shorthand. I cannot be sure, never having learnt it myself and still remembering the relief when I rose to a position on The Times where no one could expect it from me.

‘What made you so sure what he was saying?’ She picks up a book from one of her new stacks on the floor. It is the two-tone brown copy of Kingsley Amis’s, The Old Devils, the winner of the 1986 Booker Prize, signed inside as a gift from the author ‘chez Woodrow’. Miss R might be beginning her own novel collection now.

‘I knew Woodrow well enough to recognise what was important, I say. He was not a man of mysterious depth. There were difficult times between us but not in our understanding of each other. Woodrow still affected to be a kind of father figure, helping me through treacherous shoals. He thought I was sometimes naive just as I thought him shameless almost all of the time.’

![]()

13.8.14

‘The next Senecan to give me his “wisdom, dear boy” was Ronnie, still the Prime Minister’s speechwriter despite pining quietly for the previous Prime Minister. We were in the very back of The Old Rose. If he had something especially awkward to say he would always move furthest from the rumbling Highway. That was where we liked to sit, even without a Latin lesson, whenever I could not come to the West End.’

‘Ronnie was pleased about the economic consequences of Black Wednesday, surely a White Wednesday, he said, for all Senecans. The further we stood from European money the better he liked it – as, of course, did She.’

‘He used the word “She” with delight. Ronnie and I were still feeling our way in the new era. We were re-establishing our relationship in a system intended to be so different from what came before, kinder, gentler, warmer. Although Ronnie was a man divided now in loyalties he was on this subject happy to be back with me saying what his mistress wanted him to say.’

‘He could not so easily speak for John Major, his master. To me Ronnie was still the willowy T, leaning forward like any actor playing a plotter’s part, describing the blackness inside the bubble of power as the British currency fell out of the ERM, the Exchange Rate Mechanism of the European Monetary System, its acronym then as famous as NATO or a GCSE.’

Miss R picks up one of her novels, a hint perhaps that I am heading in the wrong direction. She does not want a story about economic management but she need not worry. I am not going to tell one.

‘Ronnie was not an economist. None of us was. Woodrow could call odds; he held a profitable political sinecure as Chairman of the Tote. David was a property investor; he knew when to call markets. Frank and I were almost blind to numbers. Words were all we had.’

‘Ronnie, in fact, was almost Roman in his disregard for economics. Like Seneca, he spoke only of the moral aspects of money. He was a playwright who wrote economic speeches when someone else had provided the charts.’

‘The only time he ever talked of even meeting an economist was when recounting how John Maynard Keynes, wartime bursar of King’s College, Cambridge, persuaded him to stick to his part in the University Greek play of 1940. Ronnie liked to talk about Keynes but he never told Margaret about him. The man who believed in borrowing money to spend it was always best left unmentioned.’

‘At the back of The Old Rose the other chairs were empty. Ronnie still spoke in his lowest voice, as though learning lines. He was an instinctive, visual raconteur, a writer and a vivid source for other writers.’

‘He was not the least surprised at what I had learnt. He recounted the Black Wednesday scenes, the fall of numbingly large numbers, the helplessness as billions of pounds disappeared. He described a centre where there was no Thatcher, no economic policy, no European policy and where, for a critical time in the middle of the day, there was no Prime Minister of any kind.’

‘I listened. The line of his thought was, as often, telescoped into an impromptu play. The enforced absence of Mrs Thatcher was his prologue. Act One showed the frailty of her successor and the falling faith in the policy of imprisoning the pound in a European cell. The new element was Act Two, the twist in the story in which John Major, at a time when Whitehall needed some sort of certainty (any sort), was communing with his bedroom pillows instead of his computer screens. Without Woodrow’s corroboration it would have been hard to believe as anything other than a play.’

Miss R still looks unconvinced.

‘If Ronnie were alive in this office now, he would tell you himself about this story which, as days went on, went out to other journalists too. He quickly ceased to be shy about it. Others who claimed to know talked to others who found it useful to believe. Soon there was only one story that anyone, anywhere, with any knowledge at all, was talking about.’

‘No one yet had published anything. I called David on the phone. He did not like to talk when his words were “insecure”. He wanted me to come to Claridge’s. I preferred that he came to The Old Rose which, after some argument, he did. I was meeting Frank there later.’

‘David, when he finally arrived, knew no more than I knew already. He was reluctant to believe that I was a conspirator or had made the whole story up. As a conspirator himself he did not want an amateur threatening his status. He agreed that there must be something in what I told him.’

‘He had become more distant in these different days, a different man from the boaster of the Falklands War, the Miners’ Strike and Wapping. I was now the Editor. His heydays were almost forgotten.’

‘Not so long ago David had been as aggressive to her “enemy within” as to her “enemy without”. He had led the aggressors. None of that was wanted now. Sex, ideology and agriculture were his lifelong hobbies but the second was out of fashion and the third was fun only when he had a new tractor. He was back to his position of acting out the Sixteen Pleasures in the Lanesborough Hotel.’

‘The new Prime Minister was not interested in his principles but would anyone else ever be? That was his anxiety.’

Miss R scribbles notes at any mention of principles just as she closes her book at the mention of positions. One by one she turns to face the office floor the photocopies of David’s Ariadnes and Messalinas, their arses above heads, hands gripping bedposts.

‘Mrs Thatcher was genuinely principled’, she adds with a voice raised as a question.

‘Yes, indeed. The longer she had held the principles the better she liked them. When she died last year claims were made that she was a magnet for intellectuals, Friedmanites, Hayekians and the like. Ronnie would have laughed at that. His own view was that she did most of her thinking very early. She liked the clash of ideas she had already considered. She liked intellectuals but liked them less than those who dressed her own views in intellectual language.’

‘David’s principles were of unfettered freedom, a creed that made a mere coal strike into a life-or-death conflict. Even his enemies, of whom there were many, conceded that, with his “soul politics”, his legal funds and his helicopter, he made this difference – and thus made a bit of history. He came to like Seneca because Seneca helped him both to think and to seem to be thinking.’

‘David and Ronnie agreed that John Major distrusted any thinking except in a tactical sense. The new Prime Minister could undoubtedly be devious. He had staged a brilliant withdrawal to his dentist when the challenge to Margaret’s leadership came and those loyal to her were asked to stand and be counted. David had admired that. Retreat was a necessary skill, a too characteristic one as now it seemed. David admired nothing else about the new Prime Minister.’

Miss R writes a large letter H on her pad.

‘After a short period focused on women and agricultural machinery, David’s first response to the new era was to renew his plot for a New Right party to supplant the Conservatives. He especially loved its symbol, the soaring bird, the flattened M which he said would be easy for graffiti artists to paint on walls. This time he saw the core of his new movement not in anti-union miners but in suburban mothers opposed to gay sex education. He had his “shock troops” among Conservative students. He wrote his name on the plans with a sharp-pointed dagger for a D. He had high hopes of support from Poland.’

‘But hardly had these birds and enthusiasms soared when they collapsed. He cited “security reasons” and refused to mention his graffiti any more. He decided to retire to his combine harvesters, sitting out the downturn for “as long as it took”, like a canny property speculator, waiting for the moment when he might best influence the next succession.’

‘So, when we spoke about Black Wednesday, he was only a little bit curious about why so many dull and mostly unexcitable men should believe that the PM’s mind had broken down. He was out of circulation.’

‘And yet it was a strange story, he agreed, the requests for briefing that brought only silence, the revelation that in John Major’s office there was not even a functioning television aerial. He described the sudden sense throughout the arteries of Whitehall that the heart of power had ceased to beat.’

‘I listened to him as encouragement but his metaphor was by then not a new one. His fresh contribution was the thought that something should certainly be published. It was wrong, he said, that everyone inside knew what nobody outside did.’

‘I laughed quietly at that. David lived his whole life on information known only to the very few. When Frank arrived with his Seneca’s essays and a Latin grammar he laughed quietly too. We did not wish to draw attention to ourselves. The bar that was empty at 11.00 became quickly busier at 12.00.’

‘Frank did not wish to be distracted from his declensions but he did have new details which he reluctantly disclosed – on condition that we then wasted no more time on gossip. The Prime Minister, he reminded us, was in temporary quarters in Admiralty House while Ten Downing Street was being “refurbished”. He said the word as though John Major were personally choosing the curtains in John Lewis.’

‘Communications had, indeed, been less than ideal. Requests for briefings came in and nothing went out. A wire coat-hanger from a secretary’s dry cleaning had been necessary as an aerial before the television would work, only and appropriately in black and white.

When the picture appeared it showed rates of interest rising, rearing and bucking like a viper in a charmer’s basket. Every lunge was ever more fatal. If the Prime Minister had taken to his bed and chewed a freshly laundered pillowcase, who, frankly, could blame him?’

‘And now please, he pleaded, could we go back to De Beneficiis, On Giving and Getting, the right way and the wrong way to repay favours and receive gifts.’

![]()

14.8.14

‘Next day two reporters at The Times began work. Would the story “stand up”, as we say? Yes, it “had legs”. Sources were sources. We rapidly had a story. I could have been more cautious. It is sometimes too easy to confirm a story that everyone thinks is true, that the Editor has good reason to think is true. Some who knew held back. Some who didn’t know didn’t care.’

Miss R is as enthused as though she were on the hunt herself, her back against the door.

‘Why was something so unlikely so believed?’

‘Because it did not seem unlikely. There was madness and poison everywhere. More important was the character of John Major himself, not the character that his friends saw, charming, open, attractive, especially to women, but the public man, the not-Thatcher, the not-bloody-minded man, the not invulnerable to hurt, the not anything much but not her. Into the vacuum of “nots”, on top of the ordinariness that separated him from his predecessor, flowed anything comic and mundane that could fill the gaps.’

‘That afternoon Woodrow called me at the office. He liked to talk to me more now that I was Editor. He could sense drama from afar. He knew that there was drama most days. That was what we both loved and it would be many years before I began to love it less.’

‘He asked if he would be seeing me that night “in the Locarno Room”. I had no idea what he was talking about. We were having one of our “slipper wheel” quarrels. He said that I needed him as a friend at court. I said that I did not. I did not want to be at his court. Did it even exist? One of us always put the phone down briskly on the other.’

‘I did not know what I was doing that night. A newspaper editor can always say that – even dishonestly. He can always stay in his office. Normally he is safer there.’

Miss R stirs, moves to the window and changes the subject as though she has noticed a gap in her notes.

‘Where exactly was your office then? She is confused by both the destruction and preservation before us, the yellow jackets in the smoke and the grey suits flitting in and out of the heritage brick.’

I point again along the wall where we first saw the Senecans run as letters, H for Hart, J for Johnson, up on to the roof, the part beneath that thin tower on top of the Rum Store, the one like a Soviet army cigarette, black-tipped, beige-bricked.

‘That was where I worked, under what was a chimney once. In the days before The Times came to Wapping it funnelled the furnace of some forgotten industrial malpractice. That was where I most felt the thrill of the job, the sense of the centre of a web, the place where I decided what to do and what others should do, instantly and without question, most of which I forget, some that I remember more clearly now.’

‘The carpet tiles smelt of sour wine. The floor was damp from leaks in the roof. The evaporation of my “new editor’s” celebratory Good Ordinary Claret took weeks. Woodrow disapproved of the choice of drink, (surely something better could have been found for such an occasion) but he had come to my windowless bunker party nonetheless. He was still anxious about his column. He could not afford to lose it.’

‘He had forgotten, he said, how disgusting our Rum Store was. Seneca’s Rome had sewers that were more suitable than this squat brick tube. It was just as the Queen Mother had described it to him. Did I remember how we had marked her official visit by taking her on a much too exhausting walk, how her Dubonnet had too much lemonade and how some mannerless creature had asked her over lunch whether she was keeping a diary?’

‘Yes, I did remember and how we had planned to brighten the brick and concrete with roses but had balked at the cost. I confessed that I had been the host without manners on the matter of the diary. He knew that already.’

‘We had reached a new uneasiness. Six years after the lunch with Kingsley Amis, despite the “slipper wheel” and what he saw as my dangerous naivety, I was more in control than before. Margaret Thatcher’s court was gone. All courtiers were out of fashion. Woodrow was still a Times columnist but, in the new era, there were even more of my colleagues who thought that he should not be.’

‘But at 7.00 pm, just as he had known and said that I would, I arrived at the Foreign Office and climbed the wide marble stairs to the Locarno Room. I felt tired. A man I barely knew asked if I was well. I sipped a drink and wished I had not. There were already dozens of thick necks in this grandest suite of Her Majesty’s grandest department. I tried to look closely without looking at anyone in particular.’

‘I knew why I had come but, even before I had taken ten steps, I knew I should have stayed beneath my chimney. Another unknown man asked after my health, politely but firmly. He looked to me like one of the men in The Undertaking, that Greenwich play on my first Thatcher night, a pinstriped fraud on a stage with the fantasising dead.’

‘I wondered if I should leave. The neck of the man asking me questions was built of triple-layered folds from one flat ear to another, a pitted nose, heavy-lidded eyes propped beneath a bright broad forehead where wrinkles ran like waste pipes. His colleagues looked much the same and it was as hard at first to see between the pillars of neck as to tell their double-breasted owners apart. At least I was suitably suited myself.’

‘The quieter places were beside the walls, an alternating pattern of panels in blue and gold. I could already see Woodrow who had chosen blue as his backdrop. His thin white hair, streaked carefully over his shining skull, absorbed the same jewel-like blue. These rooms, the invitation told us, were newly restored to their grandeur of the 1930s.’

‘A junior foreign minister was showing off the work. When Woodrow had asked me whether I would be “at the Locarno Room for the Lennox-Boyds” he made it sound as though it were a dinner. I had said not. But there was something in the Editor’s office diary about the Foreign Office and this was it, fortunately as it turned out because by then there was something important that I needed to tell him.’

‘Woodrow was buried in the party’s first half hour by the bulk of other people. I watched him. I met an American friend whom I genuinely wanted to see. I began to feel better and a bit guilty. To compare the Locarno Room to a mortuary of the surreal was an exaggeration. I had to beware exaggeration.’

‘Where I stood was more like a gallery of plaster casts, thick white shapes, eighteenth-century copies of Roman heads, Renaissance copies of Greek originals, solid ghosts, ghostly nonetheless, politicians and bureaucrats with that peculiar spirit quality that comes when avoidance of trouble is the highest art.’

‘Seneca would have fitted in easily among the Locarno crowd, the Seneca of his best surviving portrait, a double bust from two centuries after his death in which he shares a block of marble and, by not very subtle implication, a mind and brain, with the face of Socrates. Woodrow was blending in with natural ease, his forehead just a little shallower than Seneca’s, his chin sharper, his eyes set in false mockery.’

‘My columnist’s bowties were hardly classical. Nor was the unlit cigar by his belt which he wore as though it were a pistol or a whip. But he and Seneca shared much of the same space, merely a trapdoor of time between them. There was so much else that these two shared (or so it seemed as I watched and waited, waved to men I knew and drank warming white wine), a relentless insecurity, a raw nerve in every jowled crevice, a resolute desire for principle as well as power, pleasure and its resistance.’

‘This was not intended to be a Senecan night. Woodrow had anyway proved himself the least attentive, the least inventive, of the group. I had one specific piece of business, to tell Woodrow about the article that had come from his unknowing phone call, now already on The Times presses for the following day, a short but striking story of John Major’s melancholic state of mind, maddened, said some, miserable, said all, and what that meant for what happened when his power was collapsing all around him.’

Miss R is being patient despite herself. ‘Was Woodrow the only one who “knew”?’ She voices the quotation marks of doubt.

‘Oh no. Woodrow was one of many in the Locarno Room who “knew” about the “black dog” that bit the PM on the day that he lost his economic policy. But he did not know what was about to be said about it in The Times the next day. That was what he would have wanted to know the most. The Black Wednesday event was in the past, but not yet safely in the past. Woodrow knew merely what had happened, alongside others of the sharp-nosed, the thick-necked and at least one well informed woman.’

‘There was a small group at the end furthest from the entrance, “where Lord Salisbury had once had his desk” a man said, “where the Locarno Treaty itself was signed” added another. This area was as though roped off by invisible red threads. No one approached too near. I recognised there one of the most powerful marble men who, in Frank’s report to The Old Rose, had spoken of the hour in which the heartbeat of government had stopped.’

‘Amid the rest of the throng there were two others who had done the same, with added details about pillow-biting in the purple-plumped upholstery of the prime ministerial bedroom. How did they know? They had reliably heard.’

‘“Can Major take the strain?” ran the headline when I left the office. “Did he crack up?” asked the second paragraph. Journalists were quoted. “Friends of” were invoked. Minor errors were still unspotted. It was not a great piece of work but a gripping one. The first edition was already rumbling towards the presses, soon to be on its way to Cornwall and Scotland and to those desks in Whitehall whose occupants had the task of seeing first what others would see soon enough.’

‘I was still keen to tell Woodrow before he learnt of this from anyone else, or still worse from the morning paper itself. I owed him that, a debt of etiquette even though he would be horrified, I was sure, to hear what I had done. Or maybe he would have pulled back his shoulders like a sly bird and laughed.’

‘An adviser likes an early warning whatever his view of the news. How can he advise what others cannot advise unless he knows what others do not know? He wants to know when every little bomb will explode, particularly when he is one of those who have lit its long and multi-stranded fuse. Woodrow would never know about the fuse (I would naturally protect my source from himself) but he was never going to know about the explosion if he stayed inside the knot of statues beside the blue-panelled wall.’

‘I slipped out to the foot of the stairs, thinking that I might catch him as he left. I wanted to speak to a few others too. I wanted to speak to David and Ronnie and to Frank but none of them was necessarily going to be there, Frank the most likely, David almost certainly not, Ronnie, well one could never be sure. Then suddenly, and behind the last curve of the staircase, I saw all four of my Senecans, the last time that I ever saw them all together.’

‘This was absolutely a surprise. Events were ever more driving us apart. Frank and I kept up a little Latin and some plotting against some mutual enemies but he had adopted the distance from the Senecans that he thought appropriate for the new Deputy Editor of the Sunday Telegraph. Woodrow thought David now as nothing but a spiv, Ronnie as a pen-for-rent who was lukewarm to John and a fanner of Margaret’s worst Queen-over-the-water fantasies.’

‘David thought Woodrow a toad and Ronnie a useful idiot. Ronnie, while still happy to play Seneca with me, thought David a bit deranged, very dilatory at Latin, and he did not think of Woodrow much at all. But this time, this one and final time, they looked like life-long friends.’

‘Ronnie and David stood apart but talking. Between them were two locked bicycles, not a standard Foreign Office feature and neither of the machines belonging to my conspirators. I say conspirators because on this occasion they truly did look like conspirators too, as though they intended to be seen in a conspiratorial pose or, at least, did not at all mind.’

‘I was confident about the non-ownership of the bicycles because Ronnie still rode only in his elderly Rolls Royce which he could always somehow, somewhere park. David liked best to travel by helicopter, often piloting himself, dreaming of swoops against striking miners, somehow maintaining his licence even when the wasting disease had destroyed the voluntary use of his limbs. On land he was always driven – by a man in a Mercedes, not always the same man in the same Mercedes – and to have seen him on a bicycle would have been as unlikely as seeing Seneca or Socrates on one.’

‘I saw them together as I watched Woodrow reach the last stone step, slipping slightly on the last of the red carpeted strips, righting himself by a straightening of his tie. I think of him now as a man of slippers. He made so many jokes, threats and quotes about the slippery slopes of power. At this point he was merely mumbling his way out, mumbling towards Frank, who was just arriving, and Ronnie and David whom he seemed not yet to have seen.’

‘Ronnie and David, though talking, seemed also not quite to have met. Each was looking past the other’s shoulder like parrots kissing in cages. For David a conspirator’s cloak was a familiar guise, his essential nature as his enemies saw him. His distant stare that night more than usually brought to mind Lord Lucan evading capture for the murder of his children’s nanny, a man backed into a corner but certain that with a moustache and a limousine he would escape.’

‘Ronnie was smiling into a different empty space. He looked at that moment like the most lauded of film idols, with the kind of face that Margaret Thatcher, in so many instances, had so clear a liking for, an even, varnished gaze. David still complained that honours were her form of sexual favours. Ronnie was manifestly her type, the friend of Greer Garson and Celia Johnson, the toast of Hollywood in the years when she was still studying her chemistry books, still not yet embarked on her career as a whipper of cream.’

‘Frank was running his hand across his thick black hair, looking around, already sketching the scene into his diary. Each of the Senecans looked as their undertaker or favoured biographer would want them to look, Ronnie as open and natural as an actor can easily be, as pale as David was dark, Woodrow in a worsted hue, a spotted grey, Frank in Marks & Spencer blue. Each had his position. I was sure that later they were planning to meet.’

‘Ronnie seemed the most commanding. Margaret Thatcher’s once favourite speechwriter knew already what was coming in The Times the next day. He was almost the first to know. I had phoned him from the car. The others did not. Or, at least, they did not know so from me.’

‘Ronnie was also by a foot the tallest. This gave him the greatest opportunity for the avoidance of meeting eyes. He swivelled away as though to check on his bicycle while somehow at the same time grasping Woodrow’s hand. All four then shook hands, not what the thick-necked men up in the Locarno Rooms would naturally do to their friends. At that moment each wanted unequivocally to be a stranger.’

‘What was going on?’ Miss R asks if I know now any more than I knew then.

‘I know less’, I answer. ‘You should have found me earlier.’

She purses her lips.

Maybe both of us are going to write about this time together. She said as much at the start. My own diary began as a defence against her, just as sometimes I used to write as a defence against Frank. I am wondering about her ‘Thatcher project’ and if she is really a writer. If she is I doubt that the books will be very much alike. She is writing history. I am writing non-fiction. There is a difference.

If I were Miss R, the historian, I would have to decide on the credibility of my sources, the reliability of each man or woman whom she has chosen to interview. I would judge the significance of all the various plots against John Major, those that were real but unimportant, those that were important but imagined. For non-fiction I just record what happens in this emptying room.

Of course, if I were a novelist of newspapers, vying for a place on Miss R’s freshest pile, it would be possible to finish the story in any way I chose, finding plausibilities that might satisfy her better than anything I have said so far. If I were fully infected with fiction I could build upon an unsupported possibility a narrative in which Ronnie knows most from those closest, Woodrow hears quickly too, and Frank gleans added details from the Mandarins. Maybe Frank hopes that, by publishing them, I will prove to everyone his worst illusions about The Times. Motives of everyone would be mixed, a hope of pleasing and appeasing Margaret, a hope of advancing a new Tory leader, a hope of advancing themselves, a simple love of mischief.

Miss R puts her notebook on top of her fiction pile. She returns coldly to her questions. ‘What happened next?’

There is a call from outside, some TLS problem of today. I have to leave – and ask her to leave – before I can answer.

![]()

15.8.14

‘What happened next?’ Miss S scrawls the words like graffiti in her second yellow SENECA notebook.

I do not answer immediately. I like to answer her quickly. She is more likely to believe me if I do.

‘What happened to whom?’

‘To you’, she says.

‘Nothing, not immediately’, I reply. ‘One of Seneca’s most influential contributions to “self-improvement” was what he called his “Way”. Every night a man should think back over his day, questioning his own intentions, wondering whether a more virtuous decision might have been substituted for every decision taken.’

‘Seneca’s Way is not the way of newspapers. Critics charge that editors are too able to be thoughtless and ruthless, too powerful, too little accountable and sometimes we have all been so. We take positions and change them. Each day the present so quickly obliterates the past that a thought about an old thought hardly ever happens.’

‘Did nothing happen at all?’

‘Officially, not very much.’

‘The next time I was in Downing Street I was told by an aristocratic aide – firmly as though to a misguided child – that since John Major and I were “both from the same sort of background” we surely ought “to understand each other much better than we seemed to do”. It was “in all our interests”.

‘The next time I met Woodrow he responded with denial and rage. There was not the slightest scintilla of truth in our story. The sooner that I slipped off the “slipper wheel” the better.’

‘I repeated “not the slightest scintilla” to David. Not a spark of truth, he queried, showing off his new interest in Latin. He doubted that. Men like Woodrow always liked to use Latin words for lying. That was a good reason for learning more of their language. There surely had to be a spark of truth in the Prime Minister losing his mind as well as his temper. He would find out.’

‘The next time I met Ronnie he was unusually quiet. Margaret, he said, was doubly disappointed – both that the incident took place and that The Times published it. “The first, I think, rather more than the second, my dear”.’

‘Frank laughed. He had already moved on, just as I had, just as all journalists do.’

![]()

18.8.14

‘Yes, but how did you yourself feel about what you had done?’ Miss R has been coming back and forth for four months and this morning, for the first time, she asks the desperate question that journalists normally ask much earlier, especially those broadcasting on TV or radio. I should respect her, I suppose, for holding back so long.

How did I feel? There is nothing I can say. I am beginning to wish that I was part of a more conventional interview, one of those where the subject can promote achievements and success, provide a ‘balanced view’, ideally slightly unbalanced in the interviewee’s interests. I could describe my encouragement of young writers, some important ‘scoops’ on schools and prisons policy if I could remember them, and lunches with Social Democrats to discuss libel law reform. It is too late for that now.

Miss R and I look again together down the cobbled street to The Old Rose. I see Ronnie and Woodrow, the L and M in wary alliance. I see David and Frank, H and J, hyphenate and justify as the type-setters used to say. Together we see the plant and the spaces within the plant, red against black, black against red. Remembering Woodrow makes me remember again the roses on trellises that we thought might brighten the Queen Mother’s Wapping day. The colleague who rescued me from my ‘do you keep a diary, ma’am?’ gaffe did so by asking our guest a question about rose-growing in Scotland.

![]()

19.8.14

‘Why, if the “breakdown” story wasn’t true, was it so widely believed?’

Miss R sweeps her eyes this morning across the piles she created yesterday. I look back at her in mock surprise.

‘Who’s saying it wasn’t true?’

‘Almost everyone, as far as I can see.’

‘But that is because John Major is now respected. Everyone who came after him was so much worse. The same thing happened to Roman emperors. The best route to a glorious reputation is to be followed by fools.’

‘The early 1990s were such a crazy, toxic time. A “believing age” had been replaced by a different age, a brutal but mercifully short age, of believing anything at all. The “hard thinking” had become the “no thinking” and the “soft thinking” of New Labour was still ahead.’

Miss R flicks back through her notebook.

‘Margaret Thatcher had been forced from office. John Major had won an election without her. But in many places, among many people, it was as though she were still in power – or still about to return to power. Nero was the same.’

‘Did you keep up the Latin lessons?’

‘Since Frank had now joined Lord Black at the Sunday Telegraph, he and I met less often. But at least three of us still met occasionally in The Old Rose, still talking, at Frank’s insistence, mostly of Latin matters.’

‘Ronnie was the most regular other attender, Woodrow the least. David said that there were certain times when simply no one could discern fact from fiction.’

Miss R looks blankly around us. She point to what little is left on the political shelves in a hopeful seeking of help.

‘Every reader who cares can now know the official history of the 90s. There are countless books, some of them here about to be dumped into their own yellow skip. No one will rescue “the Bastards’ Tales”, the boasts of how John Major was harried to defeat in 1997, never recovering from that Black Wednesday of 1992 when the pound collapsed from its European restraints (certainly), the central policy of the government collapsed (certainly) and the Prime Minister himself left a vacuum at the centre of power while he found a pillow on which to bite (possibly, possibly not).’

Once upon a time I might have written a different account of those years, a traditional Editor’s verdict with much ‘allegedly’, many cautions and caveats. This year Miss R is looking from me only for what others cannot or may not tell her. Then she will move on.

![]()

20.8.14

Each time she leaves she takes a few of the books she wants. Her mind is on the letters now. At the top of her carefully tied bundle there is one that I have had my eye on ever since she pulled it from the piles. I can tell her about if she asks. Its date is November, 1993.

Mr V barely registered John Major. Three years after the fall, the words from Walton were still of the ‘assassination’ of Mrs Thatcher. What was a fading term even among her friends was long a living fact for him, as for other adherents, a constant cause of scratchy italic rage. For years he wrote as though the coup against her had only just taken place, or he had only just now read about it, or that it might in good time be reversed.

Margaret had deserved a dignified departure, he wrote. He wrote this repeatedly. Instead, she was betrayed by everyone who had once relied on her (and that included me), shoved before parliament to answer some last questions, prodded into declaring how much she was enjoying herself, and sent away to live in a housing estate. Her successor looked like the man who used to collect the takings at the Odeon.

Miss R picks up this letter and holds it gently in her hand. I have read it many times. It is written in a pale brown ink, a colour barely browner than salt water over sand, readable only in parts even when I first received it, now hard to discern at all except by nib marks. It seems like the note of a failing man except for Mr V’s proud boast that he has returned to balsa.

He has carved a sculpture of his heroine’s final parliamentary performance inside the Palace of Westminster. He has received local acclaim for it. Photographers have visited from The Chronicle. He wants to know when I might come and see what I can so readily imagine, the green leather benches made cream, the rejected Prime Minister as a stooping letter P, the sculptor in aertex and white.

![]()

21.8.14

Miss R is agitated again today. She does not want to tell me why. She sounds like a writer who has lost confidence in her project. I have known enough of those – and been one sometimes myself too. Instead of more chronology she wants much more ‘context’. Context is her new word. She listens less and searches more. She sifts letters from newsprint and puts poems next to grammars.

‘I need more to read.’

I know now that our interview is coming to an end. I have one suggestion. Although Margaret Thatcher was never famed for encouraging the arts, this final period did inspire one too little-known novel. I can already see my copy close to where she is leaning her hand. Philip Hensher’s Kitchen Venom, published in 1996, was – and still is – the best book about this final phase of the Thatcher era.

Today it lies sullenly on the floor, in bookish protest that no one has opened it for a long time, the blue-covered version although I think there is also somewhere a cream one and a pink. It is a highly Senecan novel, dark, epigrammatic, suffused with philosophy and revenge, narrated in part by the Iron Lady herself as a deposed but not quite departed ghost.

The Prime Minister’s fall from power in 1990 is, in Hensher’s fiction, a wholly random event, as random as the murder of an Italian rent-boy by a powerful House of Commons clerk. In as much as anything is intended in the story, it is impossible to say when it began to be intended. There is an ancient sense of Fortune with a capital F.

The ‘leaderene’ and the cog in the parliamentary machine are well matched. The greatest politician of her age lovingly fingers the silk around her neck (no one has ever better described Mrs Thatcher dressing) in the same way that the subversive clerk, anticipating the fuck that has cost him £50, feels the silk of the hired boy’s skin. The mistress of politics in her prime crushes the world like a dead cigarette with every high-heeled step she takes. But the clerk crushes whichever politician is in power, concentrating most of his mental energy on remembering the name of every Trollope novel.

Venom is as ubiquitous as alcohol. Fierce intelligence is everywhere, too, most of it useless and pointless. Haunting is his theme. His heroine remains for some while as a spiritual presence in Westminster and Whitehall, passing on her power ‘in a command and a request’.

‘You might enjoy it. You should add it to your reading for after The Line of Beauty.’

But her agitation has passed.

‘Are you pleased that you became a journalist?’ She asks this question slowly, as though it is the one she has long most wanted to ask.

No one has asked me that for a very long time. This is an even more desperate question than ‘how did I feel?’ Probably the last person to ask it was the man who wrote the letters in brown ink.

‘Yes, of course, I am pleased that I became a journalist, proud too most of the time.’

‘What about the rest of the time?’

![]()

22.8.14

When Miss R came here first she struggled for space. Almost all of my boxes have now gone. But she has added piles of her own, personal letters and Latin plays, even borrowing some of the labels that read DO NOT MOVE TILL LAST DAY.

‘For evidence’, she claims with a smile, she has set aside Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils, the copy inscribed to me ‘Chez Woodrow.’

‘For atmosphere’ there is now Kitchen Venom as well as The Line of Beauty.

On top of the pile is Ian McEwan’s Amsterdam, its cover a frosty scene of French duellists, name and title in brown, winner of the Booker Prize in 1998. ‘This one is a bit about you’, she says as she sits down on the floor.

I try to look surprised. I am not wholly surprised. It is an identification I have heard before. ‘Some said Peter Stothard, others Alan Rusbridger. But I have no idea …’: that was how the author himself put it, writing in a presentation copy for charity last year, words extracted by the Guardian, edited by Alan Rusbridger.

McEwan was being mischievous maybe but I can hardly blame him for that. Mischief is what writers make. For Miss R, newly interested in my pride or lack of pride, in ‘how did I feel?’ or how did I ever feel, Amsterdam is a reasonable destination.

‘Tell me about it’, she says, by which she means, I think, that she genuinely wants me to tell her, not that her question is of the ‘tell-me-about-it’ teenage kind.

‘McEwan’, I try to summarise quickly, ‘has two rival characters, the duellists of the cover. The musician in the foreground need not concern us, but further back there is a newspaper editor, a man in charge of The Judge, a paper not unlike The Times. Maybe I have the two men the wrong way around. How do I know? I don’t. It does not matter.’

‘The story need not concern us either, only the character of the editor, Vernon Halliday, who responds to a story of political scandal with bouts of confidence and hubris, self-righteousness and self-criticism, shock at the effects of his actions and reasoned doubt about whether he is doing anything at all.’

She opens the book, finds some blue-pencilled quotes and notes the passages, page numbers first. She reads aloud, not in her glass-etcher’s voice but softly and slowly.

‘After talking to forty people in his first two hours of work, offering “opinions that were bound to be interpreted as a command”, Vernon finds himself with thirty rare uninterrupted seconds: “It seemed to him that he was infinitely diluted; he was simply the sum of all the people who had listened to him and, when he was alone, he was nothing at all.” He was “finely dissolved throughout the building” and “globally disseminated like dust”.’

‘Did you have hours like that?’

‘Not many but a few, quite enough truth for fiction.’

‘Amsterdam is set in the mid-1990s, more or less on my own editorial watch. Halliday is both a pedant on grammar and a risk-taker in the newsroom. I recognise myself there. He dismisses a story on hepatitis as too dull even for the TLS. He is described as a “hard-working lieutenant for two gifted editors in succession”.’

‘Pedantic about Latin quotes? Happy to take a risk? Liable to invoke the TLS? Yes to all of those.’

‘Both Harold Evans, who opposed Margaret Thatcher, and his successor, Charles Douglas-Home, who cheered the paper through the Falklands War, were “gifted” and, in different ways, seen to be so. I worked hard for them both – and for their successors too, including my friend, Charles Wilson, the Editor so disapproved of by Frank Johnson in the Senecan times.’

‘Halliday is a well-observed character. He is not always sure that he is alive. Few men of power ever admit that in their memoirs. That is why novelists matter. In the brief moments of the day when the Editor of The Judge is alone, a light goes out. “Even the ensuing darkness encompassed or inconvenienced no one in particular. He could not say for certain that the absence was his.” Most Editors would understand this Editor very well.’

![]()

25.8.14

When Miss R returns this morning a bookmark shows that she has almost finished Amsterdam. When I say nothing, she simply stands in the corner and reads some more until I continue my story from where it stopped.

‘As the Major government decayed, his predecessor’s ghost came ever more vividly back to life, the fiercest among the flittering flocks who pursued the new Prime Minister. The question was quick in coming. Who should replace this Tory leader who had failed to inspire? Even four years after her fall was there not still the possibility that the replacement might be Margaret Thatcher once again?’

‘There was a Christmas party, held in her museum home of signed Ronald Reagan photographs, frosted MT paperweights and an almost all-black oil painting of the hostess with a shady Tory lady. When we spoke I was wholly unready for the blasts against her successor. Three times she said that she was not looking to come back to power. Each time she looked hard about, daring me, or anyone else, to disagree. The only way to avoid her eye was to catch a peculiarly vile blue view of the Falklands.’

‘What help were her Senecans then?, asks Miss R, holding Amsterdam at her waist.

‘Ronnie became a double man in those days. Fortunately, he was well trained for that. Every time that his heroine heard he had written a speech for Major, she banned him from her presence. Ronnie tried to please both sides. He said he did not approve of her haunting Downing Street as though a part of her had never left. Woodrow claimed that he too was against her afterlife. I doubt whether, when he was with the former Prime Minister, he defended the new Prime Minister very much.’

‘In Ronnie’s mind there was never a doubt that Margaret still mattered. He always believed that if Mrs Thatcher felt well (a state she regularly discussed with him) she really was well. If she was well (a truth he would always readily believe) she would speak well and that if she spoke well (which, under his direction, she usually would) she would act well. He still believed this even though it mattered less now. He wished he had done even more when it had mattered more.’

‘Although Margaret had been out of power for two years, Sir Ronald Millar, in his own mind, was still a national benefactor, keeping the ousted queen alive. This life of hers was not in his playwright’s mind alone. To Woodrow Wyatt and David Hart – and to many more from the Locarno Room and beyond – Mrs Thatcher might still be needed again.’

‘Ronnie often recalled in The Old Rose how long after Nero had fallen to his dagger, years after his last cry of “O what an artist dies in me”, Seneca’s pupil still had supporters in Greece who were sure he was coming back. No one liked to criticise his repetition. It was something of a comforter for him. Frank saw Margaret in something of the same light, her stalwarts as exiled cohorts landing at Clacton, like William of Orange at Torbay, meeting up with local worthies such as Lord Tebbit, assuring her that Essex was rallying to her side.’

‘Frank mocked but he also yearned. In the traditional ways of the Conservative Party a former leader had to be either loyal or dead. But Mrs Thatcher’s own bitter predecessor, Edward Heath, had rewritten the rules. There was now an ousted dictator role in British politics, just like in Argentina, he would jollily say.’

‘Margaret herself had entered the House of Lords, a desperate fall, thought David, although he would have loved the humiliation for himself. There was still a range of possible uses for the newly ennobled baroness, to push her successor in the right directions, to promote a better successor if one were needed. If the idea of a Thatcher Mark Two, fresh and repolished, were wholly absurd, David might yet make the Lady think that it was not.’

‘For Woodrow she was a ripe fruit that had to be kept from rotting – by flattery, by drink, by calls upon her party loyalty to stop being an angry ghost and to help John Major where she could. She always told the Voice of Reason that she was heeding his advice. She was inconsistent in keeping to that pledge.’

‘Woodrow said that David was a menace, increasingly obsessed by the SAS and the Bravo Two Zero books about its heroes. Margaret was “history”, that most respected state of comfort and condemnation. She must remain as history. John had to remain as Prime Minister. The Labour Party would destroy itself as it so often had before. Most importantly, Woodrow had to remain. Every adviser was fine as long as Woodrow was fine.’

‘And the lessons at The Old Rose?’

‘The spirit of the Latin lessons was now almost gone. We rarely tried to persuade one another. For David, Margaret was a long dying animal, ready soon to be stuffed as an icon for followers of some spiritual successor, hand-picked by himself. For Ronnie she was still the star whom he had helped to mould. For Frank and me she was a subject who, as time moved on, became less of a subject.’

‘Margaret herself was mostly more pragmatic than her ghost, more realistic than the image her admirers made of her. Although she never forgave Ronnie for working for John Major she needed him to write her own speeches and gradually the two were warmer together again. He had always been much more than a speechwriter to her. She saw that more clearly now, he suggested slyly.’