![]()

26.9.14

After three weeks beside the bridge over the Guadalquivir it is time now to go back to the Thames, to colder sky and a plant that will be no longer dying but dead, its power to make memory gone. My last sight through my window was of new machines arriving to replace the wrecking cranes, mobile cement factories, corkscrews two-storeys high. That will be someone else’s sight when I return.

Here in Seneca’s birthplace the destruction of brick and stone goes more slowly. The Cordobans ground grand marble into lime for centuries after the Romans left. Much of the very finest art in a city of fine arts was lost. The better the statue the better the cement it made, or so the builders believed, and modern builders say that they were right.

The evening air is warm. The light is grey and golden. I have watched with tourist eyes. I know the skyline better than I knew my old view back home. I can name the minarets. The walls of mosques and monasteries crumble into soft low clouds over this slow, beery river that the Romans called the Baetis, its banks today silver with the sheen of birch.

Out in the flat stream there are flat-bottomed barges like the one that two thousand years ago brought olive oil and elephant bones to the baths beside The Old Rose. In a modest contribution to progress workmen spread steaming tarmac over cobbled stones.

After five months of ‘first times’, it is time for a few now of ‘the last’.

Mr V is dead. His daughter wrote a note to the TLS that arrived here yesterday. She asked if I had enjoyed my last months at Wapping. She thanked me for helping her daughter. She was pleased to hear that I was so well. She hoped that the youngest V had been well behaved and had not dressed too strangely.

The letter described how a white-dressed body was found by a man delivering a parrot. The owner of the petshop was the only holder of Mr V’s keys. There was a half-completed balsa wood castle in the house, maybe the Tower of London, a large cage and a letter saying that the new bird should be ‘ideally white like Old George’. All of that should be buried with their owner but probably will not be.

Her daughter was not a deceiver. V was anxious that I should not think that. She was a good daughter, better than her mother, similar in views, smarter at work, inclined to easy assumptions but then she was still young. Even her grandfather became proud of her by the time he died, despairing of her politics, proud of her job, just as he had been proud of his birds and balsa.

Perhaps he was. I somehow doubt it but nil nisi bonum de mortuis. Whatever Mr V thought of Miss R, I am as grateful to them both as to the tumbling walls of Wapping. There is much that I would not have remembered and written on my own.

Finally, the last of the ‘last times’.

I am pleased that none of the Senecans was at Margaret Thatcher’s ‘ceremonial’ funeral, that none of them saw her devourers cry ‘the Witch is Dead’ and her devotees win the war of noise. Little that was said on that soldiers’ day recalled the courtiers, the writers, the plotters. On her death certificate she was a Stateswoman Retired.

Woodrow was already long dead by then – though not to the angry subjects of his posthumously published Journals. After surviving barely six months of the Blair era he lived on in a livelier art than he had ever shown in life itself. I think of him as dead in the morgue but still dictating. He kept his racecourse pass at the Tote because Margaret Thatcher renewed his chairmanship as one of her final acts in office. He kept his column in The Times almost to the end.

Remembering him has made me think more about Beryl Bainbridge. She died in 2010. I will read Winter Garden again. Colin Haycraft died before her in 1994, leaving rumours of their relationship that confirmed Woodrow’s worst suspicions. When I get home I will see whether Duckworth, now owned by the no less legendary Peter Mayer, might be publisher of The Senecans.

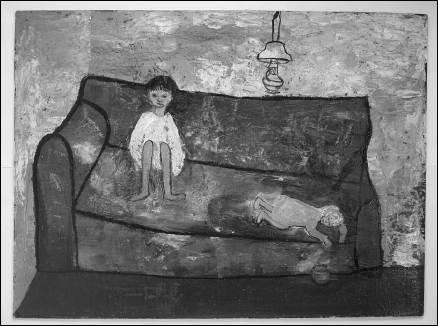

I am also going to buy one of Beryl’s oil paintings from the 1960s. I have seen it in a gallery, a picture of two children on a broken, sloping sofa in a yellow room, a peculiar reminder of the house in Walton-on-the-Naze where I first saw Seneca fifty years ago. Perhaps we could use it in the book.

Wapping said goodbye last week with rumbling and the wreckers’ roar. Cordoba has been whispering its welcome. Welcome, or so I hear this city say, to the man in the pink cotton jacket, welcome from the birds of the abandoned water mill, the pigeons in the niches cut for saints, Cordoba’s clouds of inland gulls, its canaries in cages, its parakeets, too small for the taste of Mr V, in multi-coloured packs in its autumn trees.

The most popular attraction here is a great mosque of columns and gardens, the Mezquita, a forest within walls, a survivor from the ninth century when this city was the most prosperous in Europe, an Islamic university reviving Aristotle and Cicero, Seneca and Plato, passing the best of antiquity to modern minds. Its most peculiar attraction is inside it, an opulent Catholic Cathedral: the two together would have made a perfect balsa subject for Mr V.

We said goodbye to Ronnie in June 1998, only six months after Woodrow. Margaret Thatcher and John Major, both by then former prime ministers, each avoiding the other’s eyes, listened to a young boy reading John Masefield’s Sea Fever in the actors’ church in Covent Garden. Sir Ronald Millar had only a short naval career between Seneca at King’s and Hollywood with the stars but he was proud of his ships. ‘I must go down to the sea again’ he would recite sometimes when his Tory masters were madder than he could bear.

A photographer asked for a picture of the two together. John Major readily agreed but it took only the most direct request from me for her to join him, her eyes staring skywards as though seeking redemption. Afterwards at the Savoy, Ronnie’s spirit flittered disapprovingly while his two clients avoided each other, both of them staying on for hours, Sir John chatting to the theatrical antiquities, Lady Thatcher to survivors of her court. ‘I’m piling up my cannonballs’, she said with a narrowing of her eyes and a pause: ‘for when they are needed, really needed’.

Against whom? Her successor was by then as much a part of history as she. Against New Labour? It did not yet seem so. We could only guess. And then she too began to recite Sea Fever, ‘and all I need is a tall ship and a star to steer her by’, warmly, gently, just as Ronnie always tried to see her.

Frank never published his diary. His cancer crept up before he could. We said goodbye to him at the RAF church in the Strand. No one ever suggested that this was for reasons of military yearnings, merely that it was close to where he was born and showed something of how far he had come. In death David gave him the name ‘Franco’, a designation that he would never have dared while Frank was alive.

Our very last argument was, like all our best arguments, about journalism not politics, about who did what to whom at The Times, perversely and specifically about that England football manager, Glenn Hoddle, who in an interview said that those who were disabled were paying for sins committed in their past lives. To Tony Blair (who called successfully for Hoddle’s dismissal) and the spirit of the Blair age this was an affront to decency and reason. To Frank it was merely an expression of a belief, freely expressed and held for centuries.

The behaviour of The Times in helping Hoddle out of his job, he said, was as bad as in the Parkinson Affair and in so many others since. In fact, I replied, in those two words that always annoyed him, the Hoddle story would have been ‘out’ whether and however I had published it. Editors do have powers but not all the powers that Frank liked to think.

And so we went on, petulant, pushing and shoving to the end. So much so that, while I was with his admirers in the RAF pews, I was thinking not of his mind or wit but of the transmigration of footballers’ souls, his support of an unfashionable strand of ancient philosophy. There were writers, classicists and historians in the pews as well as politicians. Seneca would have felt fully at home as a Senecan departed. A famous opera singer sang.

The Old Rose still stands on the Highway, its bar closed, its columns bleached violet and pink, its windows boarded, its cellars awaiting the further attention of archaeologists. In Cordoba too there are minor Roman remains and more being found. Some of the Mezquita’s lower stones were cut in the lives of Claudius and Nero; so too some of those in the arches of the Puente Romano, the Roman bridge that stands here over dry stones and shallow pools, waiting for the rainy season.

Eleven columns survive from a temple to the imperial family. There are stones from the Forum beneath the floor of the Bar Council. There are no traces of the foreign-sounding flatterers who Cicero tells us once worked here, the poets who make Cordoba the oldest city of letters west of Italy.

I missed David’s death after his long time dying. I was in Alexandria at the time. He had hoped to be buried in a mausoleum on his Suffolk estate. There was a planning row which I read about in the East Anglian Times. Inside he should have had his D. H. Lawrence, his Petronius, his best set of The Positions. I doubt that he was allowed them.

The last time that I saw David at the theatre he was not watching the actors but being acted. He was a character in the play about the Miners’ strike that Miss R had heard about in her researches. This ‘David Hart’ of Wonderland was theatrically ‘camp’, which he would not have liked, and wore a sheepskin flying jacket, which he never did. David would still have been pleased to be remembered.

Up the hill from the bridge there is a modern Roman bath beside the mosaic floor of an ancient Roman house. That is where I have been spending each afternoon. Between paragraphs I have waded, swam and slid from one end of these underground waters to the other, from the hottest spring lit by a low green light, through the warm mist, along the ledges of cold stone, then round and back. The walls are dark. There are small piles of small clothes. Giggles grow from the shadows as though ghosts are laughing and loving their own laughter. There is the rhythmic slap of wave upon wall, the same sound as in the still parts of the Baetis by night.

A hundred yards away Seneca has his own cobbled square close to the temple. Black stones mark the pattern of two trees, one taller than the other, an ancient headless statue and a fountain which he shares with his nephew, Lucan. An inscription salutes their glorious fame, their incluta fama. It is popular with writers of graffiti marking the thirty years since the Falklands War. So far it has avoided the tarmac of improvement.

John Major came to Spain last year to open the Avenida de John Major in Candeleda, not too far away, where the plaque is blue and white on a yellow background next to a tobacco fermentation centre and a sports hall. The Spaniards love him because he spent holidays here and because he is not Margaret Thatcher and, even better, not Tony Blair, a ‘war criminal’ on the walls of Cordoba.

Everywhere John Major’s reputation has risen and continues to rise. Journalists love him now. At a public inquiry into bad behaviour by the press he only very gently complained at the deeds done against him in office, several of them done by me. He looked like a pale moon beaming from inner space. Unlike so many others he was not looking for trouble. He did not name names. He looked far fitter than most of the politicians gone by.

Unlike his predecessor he has avoided the House of Lords. By leaving parliament (and accepting a Knighthood of the Garter) Sir John need not any longer see the enemies he called ‘the bastards’ or the flattering bastards who were his greater enemies. There might be pleasure for him in watching them all decay, but greater pleasure in being free of them, free, not least, to earn as much money as he can without having to justify his business to the scrutiny of peers.

He could be forgiven for laughing all the way to the finance house, as Frank used to say. He began there. He can go back there – and to his poems, maybe some about the Senecans, verses that, until he dies, I can merely, with Ronnie’s help, imagine.

By the southwestern gate of the city wall Cordoba’s greatest son has a statue in hollow bronze. This one is barely a hundred years old, a study of a strong man, more imperial than philosophical, carrying a text, possibly a play or a poem but more likely a speech. He is standing above a cascade of icy water. He looks down towards the river, to evaporating ancient walls on his left, some sturdy trinket-stores on his right, down over the banks of birches and planes into islands of birds, a sanctuary for herons and sluggish ducks, parrots who have escaped from zoos, geese who have invaded from the olive fields.