Chapter One

Alban: Dying for Faith

‘The head of the most courageous martyr [St Alban] was struck off, and here he received the crown of life, which God has promised to those who love Him. But he who gave the wicked stroke, was not permitted to rejoice over the deceased; for his eyes dropped upon the ground together with the blessed martyr’s head.’

Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People.1

Alban was a rebel, a non-conformist and a religious activist. He died for his faith; a faith whose founder also died for his beliefs by being crucified. Although not an Anglo-Saxon (he was Romano-British), he was England’s first saint and martyr. Blood and bones lie at the heart of Alban’s story, so the natural starting point for understanding this earliest of English saints is to visit the site of his tomb and remains. However, as with the majority of saints, Alban’s body was destroyed during the Reformation. Now a reliquary containing a single shoulder blade is all that sits in the heart of the magnificent cathedral in the centre of the ancient city that still bears his name.

St Albans wears its history on its sleeve. Following brown heritage signs towards ‘Roman Verulamium’, the traveller winds past medieval gateways, the bishop’s palace and historic watermills. Different-coloured stones and styles of architecture jostle next to one another, vying for supremacy and providing a visual narrative for the city’s evolution over two millennia. The mismatched grey stones of the ruinous Roman wall clashes with the cracked wooden beams of Britain’s oldest pub, Ye Olde Fighting Cocks, and the elegant cream Palladian façade of the Old Town Hall. This is a place of contrasts, and a place where the passage of time plays out before your eyes.

The undulating roads are disorientating, and the towers of the cathedral at the heart of the city dip in and out of view as visitors follow in the footsteps of Alban himself and thousands of later pilgrims, moving from the remains of the Roman town Verulamium in the south-west towards the later-sprawling ecclesiastical centre. There is a sense of dramatic climax for the modern-day tourist on approaching the grand west front of the cathedral, getting ever closer to the bones of the martyr. The Norman building, with its mismatched brickwork, square, crenellated central tower and rebuilt Gothic West End, emerges out of oak trees; it seems implanted on the landscape, and embraced by the city. Within the very heart of the cathedral St Alban’s now empty tomb nestles behind the high altar, presented in Romanesque luxury within its own quiet sanctuary.

Being under twenty miles from London, St Albans is a desirable place to live. Indeed, its location has secured its continual importance. The Celtic Catuvellauni tribe had their major settlement just a mile to the west of the present-day city, and Roman Verulamium was second only to London and Cirencester in terms of size and importance. The Magna Carta was drafted here, and St Albans School is the only one in the English-speaking world to have educated a pope. Yet, while the name of the city is well known, the character behind the name, St Alban himself, remains frustratingly inaccessible.

What we do know is that the Alban who became England’s earliest saint is remembered as a convert from Romano-British paganism to Christianity during a time of great change and unrest. He lived during the third to fourth centuries, when the Romans in Britain had absorbed Celtic culture beneath their mantle and seemed all-powerful. Yet this was a time when, spiritually, people were searching for alternatives to the stagnant imperial cult.2 Across the Empire new religious groups emerged with mysterious rituals, like those focused on eastern deities such as Mithras, or the Egyptian goddess Isis. Among these mystery cults, a seemingly innocuous group emerged who celebrated the coming of the Messiah predicted by the Jewish faith, and focused on a poor man from Galilee named Jesus. Although their impact was minimal in the first century after their founder’s death, Christians soon began to permeate society, particularly because they had to be literate in order to read their sacred texts, and their literacy made them valuable civil servants.

Yet their beliefs made them different. Because they were monotheistic and held to the commandment that they should worship no other gods, they were seen as dissenters. Across the Roman Empire, Christians were persecuted and died for their faith.

Certain emperors were more vehement than others in pursuing and punishing Christians, the most infamous of which is Diocletian, who in AD 303 issued the ‘Edict against the Christians’. This demanded that books and buildings were destroyed, and Christians were not allowed to gather together. There were attacks against the Emperor in response to the edict, and widespread executions followed. Diocletian’s own butler, Peter Cubicularius, met a particularly grisly end, as he was stripped, strung up and had the flesh torn away from his bones. Then salt and vinegar were rubbed into his open wounds, before he was finally boiled alive.

Diocletian had good political reasons for punishing Christians: they were non-conformists. Other religious groups, particularly those with polytheistic elements like the cults of Isis or Mithras, were shown a greater degree of tolerance. The essential premise of worshipping the Emperor was upheld throughout the Empire, and as long as people were willing to recognise him and sacrifice to his image, their individual faiths were less worrisome. But at the very heart of Christianity and Judaism, in the Ten Commandments lies the refusal to sacrifice to false gods.

It is this rejection of divinities other than the one Christian God that led to the early martyrdoms, since this refusal to conform to the state and its official religion was subversive. Martyrs, however, chose to embrace a heroic death in the eyes of their followers, and the cults that grew up around them were similarly a form of dissension against the Empire. These hero-saints laid the foundations for future attitudes that bound sanctity to suffering, self-deprivation to divinity and fortitude to fortune. Alban was one such martyr-saint. By opposing the Roman authorities he was refusing to subscribe to the status quo. He died because he chose Christianity, but the stance he was taking was more than religious. He was standing up to an oppressive dictatorship, which had transformed Britain and subjected its native people. He was a political activist prepared to die for what he believed in.

Who was Alban?

Saint Alban was a Roman-Briton who was killed by Roman authorities for refusing to sacrifice to the Roman gods. According to the earliest sources, he lived and died in Verulamium, close to the cathedral in the town that still bears his name. His cult was not forgotten, despite the fact that the site of his martyrdom moved from Roman hands to those of pagan Anglo-Saxon for some two centuries. The memory of the place where he died and the major events leading to his death was transmitted down the centuries like an elaborate Chinese whisper. His is a story of conversion, fanatical dedication, persecution and martyrdom. His is the story of the earliest Christians in Britain, and an echo of the cults that emerged across Europe in the first flowerings of this new religion. To date he has been consistently put forward as a replacement for St George as patron saint of England.

The story of Alban states that he took in and gave shelter to a fugitive priest who was hiding from the authorities.3 The priest stayed with him, and in this time Alban became enchanted by the new religion he preached. When he was finally discovered, Alban managed to deceive the authorities by switching his clothes with the priest’s, and went with the soldiers in his place. This deception, and his declaration that he would not sacrifice to the old gods, but instead embrace the new Christian God, led to his martyrdom. This is the little of his life that has been repeated down the centuries.

According to this account, Alban must have been brave to give sanctuary to a Christian during a time of persecution, and open-minded – or possibly easily led – to be influenced by what was an outlawed religion. He was outspoken too – unafraid to stand up to the inquisition of the authority figures in his Roman town – and so bloody-minded that he refused to take the easier route of public sacrifice, instead choosing a painful death over life. He was a religious fanatic, dying for his faith as religious martyrs continue to do today. Alban could even be seen to represent the notion of jihād, ‘striving or resisting in the name of God’.4 It can be hard to fathom why people embrace martyrdom, but for Alban death was a release that allowed the promise of greater reward in the afterlife.

Saint Alban takes us back beyond the boundaries of the Anglo-Saxon period (traditionally beginning in the fifth century), to the earlier Roman, and even Celtic, roots of the country. While not an Anglo-Saxon saint, much of Alban’s life and legacy were recorded and crafted by later Christian Anglo-Saxons, and what we know of Britain’s protomartyr can help illuminate the cultural and religious climate that the early Anglo-Saxon settlers encountered when they settled in England. During his lifetime Christians were persecuted, but there was also a climate of religious change, evolution and syncretism.

Around the end of the third and beginning of the fourth centuries, the religious complexion of the Roman Empire was changing. This was seen clearly in art, where the imagery of different cults was drawn together in an attempt to find common ground, with the prevailing interest in salvation and life after death. This could explain why St Alban was persuaded by the Christian priest he gave refuge to that the saving message of Christianity was pertinent and worth dying for. He may have listened to the prayers of the renegade priest and found the ideas attractive. Alban can be seen as a rebel, defying the establishment, and a convert, entranced by a basic understanding of a faith he had only recently accepted. When we compare this with the lure of religious cults or the campaigns of ISIS today, the similarities are compelling.

On the Trail of Alban

The earliest saints were made of stern stuff, and so were the readers of their hagiographies. Some saints’ lives make for unsettling reading, with detailed descriptions of the torture and suffering they endured. The Gothic tastes of later centuries, and the fascination with blood and horror that continues today, was just as strong in the Anglo-Saxon period, and saints’ lives were the main conduit for these visceral narratives. The details surrounding St Alban’s martyrdom are shrouded in mystery, but at the heart of his story lies a bloody and dramatic death, complete with his beheading and the executioner’s eyes popping out as soon as he delivered the deadly blow. Despite these seemingly detailed observations, the majority of what we know about Alban the man is dressed up in hagiographical finery crafted many centuries after his death.

It is still uncertain which phase of Roman persecution he died under. While the notorious acts of Diocletian in AD 303 have been a popular theory, more recent research suggests that he may have died in an earlier wave, coordinated either by Decius, emperor from AD 249 to 51, or Valerian, AD 253 to 60.5 It is a frustrating fact that, when studying early medieval texts and individuals, dating can prove almost impossible. Alban may have lived within a hundred-year time span – between the third and fourth centuries – which is as vague as saying Winston Churchill may have lived between the 1880s and the 1980s. So much can change in the course of a century, and while these incredibly broad chronological scales have to be accepted by scholars, it makes any accurate context for the saint’s life difficult to establish.

The first surviving textual reference to Alban is in a text written around AD 396 by a bishop of Rouen called Victricius.6 He had travelled to Britain to settle a dispute that had arisen between the bishops – an indication that Christianity was established enough by the end of the fourth century for bishops to be settled across the land. Victricius doesn’t mention Alban by name, but does record that there was a native saint who ‘told rivers to draw back’, and this detail connects him with later versions of the story. However, the first named reference to him comes from a fifth-century text written about another saint, The Life of St Germanus. There are only passing references to Alban, since the majority of the text focuses on the work of the Gaulish bishop Germanus in refuting the Pelagian heresy that had been spreading through Britain around AD 429.

The author of this heresy, Pelagius, was most probably British, and he called for greater austerity in the Church, a stronger sense of free will, and argued against predestination as set out by St Augustine.7 He was very popular in Britain, but his claims made him heretical in the eyes of the papacy. Throughout the wider Christian world, Britain was starting to be connected with practices that were deemed unacceptable, and the Orthodox Church intervened directly. Germanus was sent to St Albans to combat the followers of Pelagius, and he conducted a successful diplomatic mission by preaching to the Britons and turning them away from Pelagius. There may even be the remains of a large open space in the fifth-century town where Germanus met with the Britons – archaeological evidence for a papal mission to direct the early British Christians away from the stain of heresy.

The Gaulish bishop found an opportunity to focus the British away from the heretical Pelagius and connect them instead with a far more acceptable rallying figure – the martyred saint, Alban. In a symbolic act, he opened Alban’s shrine and placed alongside the martyr the relics of the apostles. This piece of propaganda would have presented a powerful message for British Christians to follow the orthodox route.8 And what more orthodox a saint was there to follow than one who had died a traditional martyr’s death at the hands of Roman pagans like Christ himself? While the account from Saint Germanus’s Life does not reveal much about Alban, the important fact is that, by the fifth century, the saint was firmly linked with Verulamium, his cult was still active and he was seen as a fitting rallying point for the Church in England.

The British cleric Gildas also mentions Alban. He is a complex writer, and his sixth-century text On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain gives tantalising clues as to the state of the British Isles during a period of great social and cultural change. It is written as a sermon, and is full of dramatic language and hyperbole designed to give a ‘fire and brimstone’ account of the decline of Roman Britain, seen as the inevitable punishment for a weak and sinful people. While there are historical facts within the text, Gildas is primarily moralising, so his text has to be sieved through carefully, particularly when he is describing the life and death of a man who lived centuries earlier.

In terms of his account of St Alban, it is revealing in the first instance that he chose to include his martyrdom at all, since again it shows that the saint’s story was preserved down the centuries; Alban clearly mattered to the British. However, Gildas makes some interesting assumptions about the events of Alban’s death. For example, he describes how the saint separated the River Thames in a manner similar to that in which Moses opened up the Red Sea. Given that the river that runs through St Albans is a higher branch of the Thames known as the Ver, rather than the Thames proper, this casts some doubt on the accuracy of Gildas’s account. The importance of this act of draining the Ver, however, would not have been lost on the Romano-British living in the town at the time of Alban. The river was believed to be sacred, and many finds have been discovered there, which suggests that Britons made offerings to it and valued it highly. Gildas’s account of the saint manipulating the sacred river would have been a powerful sign of his sanctity in early medieval Britain.

The primary author on the majority of early Anglo-Saxon saints’ lives is the Venerable Bede. This one writer is the all-pervading voice underlying all work on early medieval Britain, and this study is no exception. Without Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People we would be able to reconstruct only a fraction of the dates, names and events of significance from the so-called Dark Ages. We would be greatly impoverished without his accounts of Anglo-Saxon saints, too. Yet it does rather leave us at his mercy. What Bede includes, or doesn’t include, in his texts has become canonical, and we depend on him for the foundations of many of our saints’ lives, not least that of the first British martyr and recorded saint.

The fact that Bede wrote about Alban in the eighth century, while the saint himself was most probably martyred in the third or fourth, suggests his legend had been continually transmitted. He records that, having protected a rebel priest and been entranced by his promises and practices, Alban put himself forward for martyrdom in his place. The text describes the ultimate heroic act of a martyr. They must ‘put on the armour of spiritual warfare’. Alban is following the example of St Paul, whose revelations on the road to Damascus had become the defining example of conversion from the Roman way to the Christian.

Interestingly, Alban is asked by the Roman official ‘of what family or race are you?’ This brings into sharp relief the redundancy of national boundaries and geographical concepts of countries that we hold to in our modern world. In the late antique and early medieval world there were no maps, and loyalties or allegiances were determined by whom you were related to, or whom you owned fealty to through social ties. National identities were not a priority, but kinship and bonds (religious, political, economic or social) were.

Bede’s A History of the English Church and People helped develop a radical new conception of identity, which was partly intended as a national manifesto, to give a sense of Christian English identity in the eighth century. Alban’s response to the Roman official’s question in this context is entirely fitting. ‘What does it concern you,’ he said, ‘of what stock I am? If you desire to hear the truth of my religion, be it known to you that I am now a Christian, and bound by Christian duties.’ Whatever Alban’s real response to the judge, which is no doubt lost to the sands of time, Bede’s treatment of England’s primary martyr reflects his significance as the major saint of the nation, and as a rallying point for a sense of Christian camaraderie rather than tribal individuality.

Alban: Resident of Verulamium

Bede records that Alban was an inhabitant of the Roman town of Verulamium, a strategically important place given its location along Watling Street and its links with the powerful British Catuvellauni tribe. There is strong archaeological proof for the location of the Romano-British town, which includes complex villa mosaics, and there is evidence of surviving Celtic practices alongside Roman innovations.9 The earlier Celtic settlement was significant, as indicated by the destruction of Verulamium by Boudicca in the revolts of AD 61. Her tribe, the Iceni, led an angry retaliation against the Catuvellauni because of their willing subservience to their Roman overlords, and by razing the city to the ground she was able to break contact between Londinium and the Roman holdings along Watling Street. Verulamium was wealthy and self-sufficient, as indicated by the fact that it was able to quickly rebuild itself after Boudicca’s fires and another later attack in AD 160. This Roman town held great significance; it was powerful, prosperous and a thriving centre where Roman urban development met with Celtic national identity.

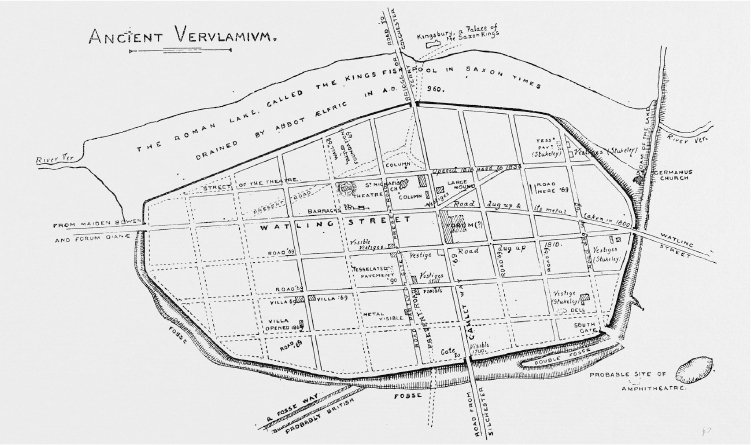

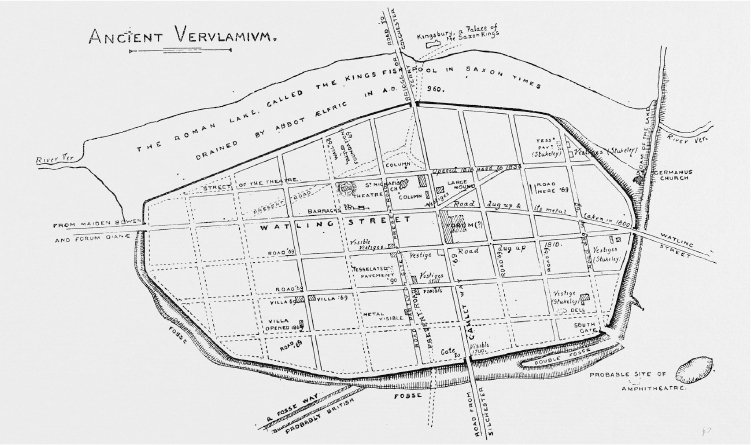

This plan of Roman Verulamium shows how it was arranged on a grid pattern, with the forum at the centre. Watling Street runs right through the centre of the town, and the River Ver bends around the northern half. Alban was martyred towards the north-east of the town, outside the walls, which is where the present-day cathedral stands.

This was where Bede says Alban lived and died. By the fourth century, Verulamium was the third-largest town in Britain after London and Cirencester, with a population of around 10,000. Having been damaged by fire twice, its timber buildings were mostly rebuilt in the third century in stone, and larger private dwellings were constructed. Alban would have walked down the grid-like street system, past stone façades and a combination of Roman and British households. Fragments of lavish wall paintings have been discovered at the site, which depict candelabra, garlands of flowers, pheasants and panthers.10 A magnificent theatre dominated the town, and at its heart a thriving market centre, perhaps the most important in Roman Britain, flourished. The villas boasted fine mosaics, Italian marble and a piped water supply.

Information about Romano-British Verulamium can shed greater light on the life of St Alban. By combining the archaeological evidence with later textual evidence, some semblance of the life and times of the saint emerge. The town was wealthy, with monumental arches at the entrances to Watling Street and grand public spaces including a forum and a number of temples. The theatre complex at Verulamium was extensive, and could accommodate up to 7,000 spectators. It would have been used for plays and gladiatorial events, including trials against animals. The location of the temple right next to the theatre suggests it was also used for religious ceremonies.

The story of Alban states that he had a house in which he protected the hiding Christian priest, so it is tempting to speculate if his home resembled those discovered in the Roman town. Of those excavated, many were large and grand, with well-wrought mosaic floors and painted walls. There was an elite residential area to the south-east of the town, and one villa in particular (Building 2 in Insula XXVII) had twenty-two rooms and a colonnaded corridor wrapped around a courtyard. The town had a number of temples, which served the pagan Romano-British population. Yet, while there is little evidence for Christianity within Verulamium, and no definitive early church, there is an interesting fixation with issues of salvation and the afterlife evinced in some of the images discovered in the town, which may give a context for Alban’s conversion.

The location of where Alban was martyred, and where his cult eventually grew up, relies partly on Bede’s account and perhaps latent memories of the site. This is not far-fetched, since the sites of martyrs’ deaths and burials had been preserved in the memories of Christians. The great basilical complex at St Peter’s has, beneath its foundation stones, the remnants of the earlier cemetery outside the walls of the city of Rome, and evidence suggests that St Peter was killed and buried at that site.

Similarly, Alban was taken outside of the city towards the arena, perhaps for his death to act as a form of entertainment. Bede records: ‘Being led to execution, he came to a river, which, with a most rapid course, ran between the wall of the town and the arena where he was to be executed.’ Recent excavations have revealed a Roman cemetery beneath the south cloister of the current cathedral, so it seems likely that this is the location, outside of the city walls, where Alban was buried.11 What’s more, when Alban got to the site of his martyrdom, he called for refreshment and a spring miraculously appeared. There is a spring of water – now known as Holywell Hill – alongside the current cathedral.

The cathedral is on the other side of the River Ver to the Roman city, and sits on a slope outside the original Roman walls. Bede’s description of the site of Alban’s martyrdom bears many similarities with the area around St Albans Cathedral, which still holds the saint’s tomb:12

Alban’s Changing World

The original saints were seen as heroes. The men and women who were burnt on fires, run through with swords and consumed by wild beasts were celebrated for the example they set to other Christians; and on a more basic level, they were enjoyed for the entertainment their exciting stories provided. Their written lives emerged from the centuries of persecution endured by martyrs in the early years of the Christian Church. The rise in saints during the third century coincided with tumultuous times within the Roman Empire. The martyrdom of Alban suggests that the religious unrest on the Continent had spread to Britain, which had otherwise been a loyal and relatively peaceful part of the empire for some 200 years.

The power of Rome was imprinted upon Britain from AD 43, when the armies of Emperor Claudius successfully suppressed the native Celtic Britons and imposed imperial taxes upon the majority of what roughly constitutes modern-day England. There was some opposition, and uprisings like those of Boudicca and the Iceni in AD 61 presented a formidable challenge to the Roman armies. But, on the whole, many aspects of Roman life were absorbed by the native Celtic population, and they adapted to the pressures exerted upon them in terms of taxation and urban development.

The Celts were not a homogenous and unified race, but rather a set of distinct tribes with links across northern Europe and Asia. Before the arrival of the Romans, Britain was composed of many separate Celtic tribes, each of which fiercely defended their borders and had separate identities from one another. However, there were unifying features between the tribes, most obviously in their language, religion and art. They were the people of the Iron Age; they set up megalithic structures, lived predominantly in round houses and created fine jewellery and armour. Their art was that of metalworking, where circular motifs – including the whorl, spiral and triskele – created patterns that contrasted light and dark areas. Understanding the Celts is essential in terms of examining Anglo-Saxon England, since their presence is never fully eradicated. When the Angles, Saxons and Jutes arrived in England they lived alongside native Celts, Romanised by three centuries of occupation, but still distinct in terms of the language they spoke, the clothes they wore and the religious beliefs they held to.

The early Celts practised a religion focused on Druid priests and a pantheon of gods connected to the natural landscape. While there was regional variety, there was enough homogeneity to speak of ‘Celtic polytheism’ as a formalised religion.13 There are certain gods and goddesses whose names appear on a pan-European level, suggesting that they were major deities within the Celtic religion. These include Lugus, who has an Irish equivalent Lugh, and in Welsh was known as Lleu. Another central figure is the goddess Brigantia, whose name means ‘the one of high’, and whose legacy continued down the ages in the figure of the saint Brigid.14 However, it is difficult to know anything for certain of the religious practices of the Celts, since they left no written records. Roman and Greek sources state that the religious leaders were known as Druids, and that they performed human sacrifices. Archaeology provides tantalising glimpses of the spiritual world of the Celtic Britons, recorded in stone sculpture and found among early temples.

There is one place, however, where it is possible to witness the ways in which Celtic beliefs were melded with incoming Roman ones in a form of syncretism that illuminates both world views: the ruined remains at Bath. Here, a Roman town grew up on the site of a previously important Celtic settlement, centred on the natural springs, which were seen as divine. The compound name given to the site by the Romans was Aquae Sulis, and the central goddess worshipped at the temple was the otherwise unattested Sulis Minerva. This compound name suggests that the Roman goddess of the hearth, Minerva, was worshipped here alongside a Celtic equivalent. This form of syncretism is evidenced across the Roman Empire, where incoming troops encountered native deities and attempted to find an equivalent in their own pantheon. So, although we know little about the goddess Sulis, the assumption is that she may have been similar to Minerva in the minds of the incoming Romans.

The name Sulis is recorded in only one other instance, and is otherwise exclusively confined to the inscriptions found at Bath. This shows that the Celtic pantheon of gods and goddesses could include those that were specific to one place, particularly to a sacred shrine, grove or spring, which is borne out in the artistic styles represented at Roman Bath. There seems to have been a conscious effort to appease the local people in terms of the temple complex. In the classical world, the central temple building (known as the aedes) was believed to be the home of the deity, where they would live in statue form during the day and be revived behind closed doors. This explains the grandeur with which temple architecture was treated. Vitruvius’s Ten Books on Architecture, which travelled the length and breadth of the Empire with the Roman army and administrators, gives clear instructions on how a temple could be reproduced effectively in fora from Britain to Syria. The gods’ homes must outstrip all human buildings in beauty and grandeur.

When the forum complex at Bath was built, it needed to house a temple, but because of the syncretic nature of the goddess worshipped there, the building had to serve two functions. Outside in the courtyard animal sacrifice would have taken place on the altars, and offerings made to the goddess. The interior, however, was reserved for the priests and those who were allowed privileged access – namely, Romans. The head of the cult statue of the goddess that would have been housed within has fortunately survived. It shows that the original statue was classical, with naturalistic proportions and an attempt at realism. This is the art of Rome, derived from Greece, which prized harmonious representations of the human body.

In contrast, on the exterior of the temple, in the pediment, is a gorgon’s head. Unlike the Medusa type, this is male, appearing more similar to Green Man representations that have echoes from the Celtic past through medieval cathedrals and beyond. This face is more abstracted and visceral, with wide eyes and strands of beard and hair creating intricate patterns. It seems that the architects at work on this temple in Roman Britain may have sought an artistic syncretism to echo the name of the hybrid goddess – the interior boasting a classically inspired statue, with the exterior presenting a different face.

All that remains of the cult statue of Sulis Minerva is a very rare gilt-bronze head. The aquiline nose, delicate hair and proportioned features all indicate that this was a fine piece of classical sculpture. In contrast, the stone gorgon head from the exterior pediment of the temple is more abstracted, with incised sections of hair and wide, deeply drilled eyes.

The incoming Romans accepted many local cults, and brought a variety of their own religious practices with them. Along Hadrian’s Wall (where as much as one tenth of the Roman army was stationed at one point), it is possible to see the extent of this diversity. Gods from the pagan pantheon, including the god of war, Mars, were venerated alongside other cults from the East, like Mithras. There is a large Mithraeum at Carrawburgh, which would have housed those military men dedicated to this elusive Eastern god, who shrouded their rituals in mystery. Another religious group was able to find a footing in Roman Britain under this climate of apparent tolerance: Christians. Indeed, a lead tablet from Aquae Sulis, written in reverse lettering, reflects the religious hybridity of third-century England:

It is clear that Christianity had arrived in Britain via Roman settlers by the third century, and it was able to set down roots more openly than in core areas like Rome. The later stories that grew up around the site of Glastonbury, which say that Joseph of Arimathea first brought Christianity to Britain and set up a religious site there, are probably the stuff of legend. But Christianity was definitely prevalent among the Romano-British population by the fourth century. However, although Christianity may have been one of the new cults practised alongside others, it was still a problematic religion at that time and could not sit comfortably alongside pantheonic faiths like those of the native Britons. While parts of the country were booming, with lavish villas erected and investment in infrastructure and architecture, there was an undercurrent of violence and persecution directed towards Christians. It’s onto this stage that St Alban steps.

What the evidence from Aquae Sulis emphasises is that, from the arrival of the Romans in the first century, mainland Britain was a complex place socially and religiously. While those in power were tied to a pan-European empire focused on Rome, the native people continued to revere their ancient gods while absorbing influences from abroad. This situation would be repeated when the Romans abandoned Britain, and those in power became pagan Anglo-Saxons. They too would absorb and assimilate elements of the native people they conquered. With Christianity, and the saints in particular, we can see the legacy of such earlier syncretism as aspects of the Romano-British past reappear. The ruins of Rome remained implanted on the landscape, and the Anglo-Saxons inherited this complex, diverse and cosmopolitan world.

Saint Alban in Context

The translation of Alban’s relics into a custom-built church was overseen by the great Anglo-Saxon King Offa in AD 793, some sixty years after Bede completed his account of the saint’s life. The event was full of symbolism and ceremony, as Offa was modelling his actions on those of worthy early Christian counterparts like Helena – the mother of Constantine – who ‘discovered’ the true cross and tomb of Christ in Jerusalem and had a huge church erected at the location. Offa, like Helena, claimed to have discovered the tomb of this important early martyr, and he was able to elevate his status by lavishing attention on the burial place of Alban. There’s an interesting connection between Helena and Britain, since a legend recorded by the twelfth-century historian Geoffrey of Monmouth states that she was the daughter of ‘Old King Cole’ of Colchester. This may not be entirely farcical, since Constantine’s father, Constantius Chlorus, was based in Britain for parts of his career; he died in York in AD 306, and could have met and married Helena there.

The man responsible for encouraging the spread of Christianity across the Roman Empire, Constantine, was declared emperor in York.16 Although Constantine only converted openly to Christianity at the end of his life, he set in motion changes that would lead it to become the dominant religion of the West. The first was the Edict of Milan in AD 313, which stopped the persecution of Christians. He then set about a building programme across the Empire, which saw the erection of huge basilical churches above the graves of saints and martyrs. The most famous is St Peter’s in Rome, but in the decades after his death other basilical churches went up over the major cemeteries around Rome, including San Sebastiano, San Lorenzo and Sant’Agnese. These churches set the blueprint for public Christian buildings across Europe, and in later centuries would be emulated by Anglo-Saxon Christians like Wilfrid and Athelwold.

The effects of the state sanctions that liberated Christians from a position of persecution were felt in Britain, where there is some of the earliest evidence for open practising of Christianity. At the Roman town of Silchester, a possible candidate for the earliest custom-built church was discovered on the south-east corner of the forum. The building has a nave and transepts, and at the end where an altar may have been is a mosaic featuring an equal-armed cross. Some doubt has now been cast on whether this was a church, but elsewhere around Roman Britain there is more evidence for early church buildings.

The earliest surviving Christian liturgical objects have also been found in Roman Britain. The Water Newton treasure contains votive offerings which could have been nailed to the wall of a church, many bearing Constantine’s banner of the Chi-Rho. A bowl with a Christian prayer inscribed on it was also found among the treasure, as well as a silver two-handled cantharus, which may have served as a chalice. The treasure has been dated to the fourth century, soon after Constantine issued his Edict of Milan. This suggests that Britain may already have had a community of Christians throughout the land, including individuals like Alban and the priest he defended, and that they began to express themselves more obviously through buildings and high-status objects very soon after persecution against them was halted.

One of the most intriguing pieces of evidence to survive and provide clues as to how Christians and Roman-Britons interacted with one another is the earliest identifiable depiction of Christ. The floor mosaic from Hinton St Mary, dated to around AD 350, provides a unique image of a male bust placed centrally in the composition and surrounded by other symbols and scenes.

The Hinton St Mary Mosaic was discovered in Dorset in 1963, and is now displayed in the British Museum. It was part of a large floor mosaic within a villa complex. Christ is indicated by the letters Chi and Rho behind his head, and he is youthful and static.

The simple representation has been identified as Christ because behind his head are the Greek letters Chi and Rho: the first letters of the name Christos in Greek. He is clean-shaven, wears a tunic and has pomegranates either side of his head. These symbols would have recalled the story of Persephone’s descent into hell, but they have been reinterpreted here as a sign of the resurrection. The fact that Christ appears on a floor mosaic, where his face could potentially have been walked over, indicates that this is an early and experimental example. In later mosaics, like the fourth-century image from Santa Pudenziana in Rome – where Christ is shown dressed in gold, with a bejewelled cross hovering above his head – he was raised up to appear on walls in an apse, seated in majesty and surrounded by the saints.

In contrast, the Christ depicted in the Hinton St Mary Mosaic is youthful, beardless, unadorned and in the traditional guise of a Roman citizen. There are other indicators in the surrounding images that this is a transitional representation – an attempt to give a new visual language to Christianity. For example, the religious syncretism prevalent throughout the Roman Empire in the fourth century is evinced by the abutting of Christ’s portrait with one of Bellerophon riding Pegasus into battle with the Chimera. That this traditional classical scene can appear alongside an image of Christ may appear incongruous, but this blending of religious ideas was common in Roman Britain, and here a parallel is being drawn between the heroism of Bellerophon and Christ. He is not suffering pain through crucifixion, but instead is shown as a hero who defeated death and the devil.

Mosaics (now sadly lost, but recorded in some magnificent eighteenth-century lithographs) from Frampton show a similar combination of themes, in this case combining Bacchic/Orphic imagery with Christian/Gnostic. It has been suggested that this shows deliberate attempts in the decorative interiors of villas to create artistic schemes that would provoke discussion among the visitors and inhabitants regarding the evolution of religious ideas in the fourth century.17 Other symbols that surround Bellerophon at Frampton include the head of the god of the sea, Neptune, and canthari, which are the vessels used to mix water and wine in preparation for entertainment. These images could carry Christian meanings, since the connection of Neptune with water may suggest the rite of baptism, while the vessels to hold wine could refer to the Eucharistic chalice. Both these symbols are repeated in mosaics from Verulamium: this location seems to have reflected a similar interest in the potential to find shared meaning with Christian and pagan myths and ideas.

The mosaics from Verulamium show that the world Alban inhabited was filled with religious experimentation. He was an early Christian convert, and around him, in the town in which he lived, others were also grappling with the intellectual drift away from the old gods. It is important to appreciate how Christianity came to Britain, how it was accepted alongside the Celtic religion and how individuals like Alban became rallying points later for the Anglo-Saxon Church, since all these elements have a bearing on the rest of this study. The Romano-British past, combined with the arrival of Christianity, formed the foundation of the Anglo-Saxon period, and Alban is pivotal in understanding this.

Not only was Alban Britain’s first martyr, but within his lifetime Christianity emerged, evolved and began to set down roots. His story helps to explain the origins of Christian belief and worship in the British Isles. In Alban we also see the power of words in how a saint is remembered. If Alban lived today he would be cast as a religious fanatic, someone opposing the status quo and seeking death as a martyred hero. Parallels with modern equivalents are there – so-called martyrs continue to die in hope of a better afterlife, and their legacy becomes what they perceive as an act of bravery in an ongoing religious war. In sacrificing his life for his cause, Alban became a hero-martyr, and the Christians that have celebrated him down the ages should remember this, regardless of the hagiographic finery his story has been embroidered in by Bede and other Anglo-Saxon writers.

Yet alongside Alban’s more orthodox story of martyrdom, cathedrals, bishops and relics, a different form of sanctity was to emerge within the British Isles. Though they weren’t martyrs in the sense of dying for their faith, the early ascetics of the Celtic Church were willing to put their life in the hands of God as they travelled across hostile terrains to spread His message, and they would suffer a form of living death in the eremitical and physically punishing existence that emerged in early Celtic monasteries. A new type of saint was emerging, and they were the products of a new monastic world.