Chapter Six

Cuthbert: Bishop or Hermit?

‘Know and remember, that, if of two evils you are compelled to choose one, I would rather that you should take up my bones, and leave these places, to reside wherever God may send you, than consent in any way to the wickedness of schismatics, and so place a yoke upon your necks. Study diligently, and carefully observe the Catholic rules of the Fathers, and practise with zeal those institutes of the monastic life, which it has pleased God to deliver to you through my ministry. For I know, that, although during my life some have despised me, yet after my death you will see what sort of man I was, and that my doctrine was by no means worthy of contempt.’

Bede, Prose Life of St Cuthbert.1

There’s something eerie about the way Bede, apparently quoting Cuthbert himself, prophesied the movement of the saint’s bones. Cuthbert’s body did in fact have to leave the place of its burial – Lindisfarne. Following the fateful Viking attacks of AD 793 the monks were repeatedly subjected to raids, until they finally abandoned their monastery and began carrying Cuthbert’s coffin and the Lindisfarne Gospels across the north of England for over a hundred years. The monks finally settled at Durham in AD 995, where Cuthbert’s body still lies. He represented so much to so many, and was the most popular English saint until Becket usurped him in the twelfth century.

An Anglo-Saxon nobleman, Celtic monk, hermit and bishop, he seems a mass of contradictions. Yet it was the multifaceted nature of this saint that made him so popular, as well as his association with some of the finest surviving Anglo-Saxon artworks. His life was recorded twice (in verse and prose) by the greatest writer of the time, his relics were lavished with care and attention, and his cult was preserved despite the destruction of its original site. Cuthbert’s name is one of the most potent to pass down the centuries, and he continues to be celebrated and venerated today, particularly on the island where he was abbot and bishop.

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne is special. It is a tidal island, joined to the mainland by a sandy causeway just twice a day, and otherwise set adrift in the North Sea as the tide rises. It is also a remarkable natural habitat, populated with rare flora and fauna. There are over 300 species of birds recorded on Lindisfarne, and among the dunes and quicksand, wild flowers and insects flourish. It is special from a historical perspective due to the Celtic monastery founded here around AD 635.

The landscape of Lindisfarne made it the perfect place for Irish missionaries to found a flagship community within the borders of Anglo-Saxon England. A causeway miraculously appears at low tide, connecting the outcrop of land to the Northumbrian coastline like an umbilical cord. The only way to reach the island was by carefully traversing the mud-plains. The safest route is today marked out by wooden piles set at regular distances to avoid dangerous areas of quicksand; nevertheless, the causeway has always been deadly, and one car a month has to be rescued after getting caught in the rapidly rising waters.

The trip from the mainland to Lindisfarne depends on the elements, and away from busy cities and motorways you tune in to the regular patterns of nature, like the rising and falling of the tides. Once on the island, swirling waters engulf the only access road, and the next opportunity to return to the mainland won’t occur for some five or six hours. The inhabitants of the island nestle together in the area around the site of the original monastery, now exuding a faded grandeur due to the crumbling ruins of the later Norman monastic complex. The rest of the island, however, is a nature reserve where the wonders of creation swirl over your heads, unfold beneath your feet and stretch before your eyes. The movement of the waters punctuates the passage of time, and it is possible to imagine the rounds of monastic prayers accompanying the eternal motions of the natural world.

The connections between Iona and Lindisfarne are obvious. While today the island perched on the western coast of Scotland seems more remote than the tidal isle off the coast of Northumberland, the history and impact of the two are twinned together. The islands are almost identical in size and population, with Lindisfarne measuring 1.5 miles long and 3 miles wide, and boasting a population of just 180 people. There is a direct connection between them, since the first monastery established in Northumbria, on Lindisfarne, had as its founder Aidan, a monk from Iona. Little is known of his life before he left Iona to found a monastery on land granted to him by the Northumbrian king Oswald. In pursuing his missionary work in a potentially hostile pagan environment, Aidan was continuing the work of Iona’s founder, Columba. However, the isle of Lindisfarne and, even more so, the tiny isle of Inner Farne, a few miles further down the coast, still resonate with the legacy of the later saint and bishop Cuthbert.

When Cuthbert sought retreat from the world of Church politics, he would head to Inner Farne, and it was here that he introduced the first recorded bird-protection law in AD 676, to look after the eider ducks, which have since been named after him ‘Cuddy ducks’. He discovered that people were stealing the birds’ eggs from the island, so as bishop he issued a law to protect them. Birds were important to Cuthbert, and a number of his miracles revolve around them. This is hardly surprising given that the cliffs surrounding Inner Farne in particular teem with nesting birds in spring. Puffin burrows pepper the ground, and angry terns can swoop down at passers-by if fearing that their chicks are under threat. The isle of Lindisfarne, its birds, beasts and vistas, continues to inspire artists, musicians and tourists alike, just as it inspired its most famous saintly resident.

Cuthbert’s Life and Times

Cuthbert lived during a pivotal time in Anglo-Saxon history. Born a Northumbrian nobleman and raised in the Celtic monastery of Melrose, his life reaches across the many religious and historical strands of seventh-century Britain. He was born a few years after the end of King Edwin of Northumbria’s reign, and his life coincides with the zenith of that kingdom’s power throughout Anglo-Saxon England, referred to as Northumbria’s Golden Age.2 Cuthbert sits firmly at its centre, and continues to fascinate down the centuries with his delicate balancing act of power and piety, humility and honour.3 To understand Cuthbert and the legacy of Lindisfarne, however, it is essential first to consider what happened to Gregory’s Roman mission when it came north, and the resistance it met from the Celtic Church, with its stronghold on Iona.

When Augustine arrived with his mission to Kent in AD 597, the kingdom of Northumbria was undergoing a period of transition. Kent was dominant among the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, with King Aethelberht acting as ‘bretwalda’ or overlord of the other kingdoms. How this manifested exactly is difficult to determine, but it seems other kings, such as Raedwald of East Anglia, sought to pacify him with gestures like nominally accepting his new religion of Christianity. The other kings may also have owed taxes or been required to provide troops in times of need. In contrast to Kent, Northumbria was a kingdom divided by rival clans. It gets its name from being composed of the regions north of the Humber, and its furthest borders reached towards southern Scotland. It was composed of two major kingdoms – Deira (from the Humber to the Tees) and Bernicia (land north of the Tees) – but as its luck began to change it would grow to include the neighbouring fiefdoms of Elmet and Gododdin.

Despite the fact that the main kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia were nominally unified around AD 604 by King Aethelfrith, conflict between the two is a feature of most of the seventh century. The situation was similar to that some AD 600 years later, when the houses of York and Lancaster placed different representatives on the throne during the Wars of the Roses. King Raedwald of East Anglia, and Sutton Hoo fame, stirred the pot of intrigue to the far north of his kingdom. Around AD 616 he defeated Aethelfrith and installed his rival, the King of Deira, Edwin, in his place. Edwin had been under Raedwald’s protection while in exile from Northumbria, and it is tempting to imagine him staying in the court of East Anglia, resplendent with stunning pagan treasures like those found at Sutton Hoo.

The links between Edwin, Raedwald and Aethelberht were to have the most profound effect on the spread of Roman Christianity to the north, for Edwin was willing to accept the new religion in return for greater links with the powerful southern kingdoms. Edwin was married to Aethelburg, the Christian daughter of Aethelberht and Bertha of Kent. It was a condition of her marriage that Edwin convert to Christianity. The moment the Northumbrian court agreed to accept Christianity is recounted by Bede in one of the most poetic accounts to survive from the early medieval period. Spoken by an anonymous counsellor to the king, the soul is likened to a sparrow flying through the hall:

While the real discussion from Edwin’s court remains forever out of reach, there is archaeological evidence for the court itself, and possibly the hall through which the sparrow so prosaically flies. The archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor was responsible for excavating the remains of an Anglo-Saxon royal settlement at a remote site called Yeavering, in Northumberland.5 Following references in Bede to ‘Ad Gefrin’, a royal ‘vill’ close to the River Glen, he speculated that an administrative complex could be located further inland from the traditional seat of power at Bamburgh. This site, he believed, was designed to exercise greater control over the native British population, who were more established in this central area of Northumbria.

After examining an aerial photograph taken by an RAF pilot on a particularly dry day in 1949, Hope-Taylor determined that there was a sequence of timber buildings close to Yeavering Bell, which itself had a history of Iron Age settlement. At Yeavering he discovered a fascinating survival – a ringed enclosure of huge dimensions. It was probably deployed to secure livestock, which the king and his retinue would use for food during their stay at the royal hall. Anglo-Saxon England in the early seventh century was not using coinage, so payments tended to be made in cattle, equivalent to hides of leather. From this emerged the Tribal Hidage – the assessment of the income of land on the basis of how many hides of leather would be paid.6 There is also overlap in the runic alphabet that was used by Anglo-Saxons. The ‘f’ rune can be interpreted to mean both ‘wealth’ and ‘cattle’, again emphasising the link between the two.

The complex at Yeavering offers many other insights into the court of King Edwin, primarily the enormous timber hall, which recalls description of Heorot in Beowulf. It is tempting to think of Cuthbert, a young member of the Northumbrian aristocracy, sitting upon the benches within a hall like that at Yeavering, watching the mead cup pass from hand to hand and listening to the accounts of heroic warriors while safe from the storm outside. Alongside the hall, Hope-Taylor unearthed an unusual building in the form of a wedge-shaped amphitheatre. Built of wood, with a raised stage at the base and seating for some 300 people on tiered levels, it has been called the ‘cuneus’. It is unique in Britain, and Bede suggests a tantalising solution as to its use. It revolves around Paulinus – Augustine’s emissary to the north.

Paulinus was sent by Pope Gregory in a second mission of AD 601 to support the work done by Augustine in Kent. He went north as a result of the marriage between Aethelburg of Kent and Edwin of Northumbria. The bishop accompanied the Kentish princess to the court at Yeavering, and began negotiations with the king about converting to Christianity:

The ‘cuneus’ at Yeavering may well be the remains of the site where Paulinus preached Christianity to the Anglo-Saxon people. The proximity of the River Glen to the Yeavering site may further support the idea that this was where the first northern Christians were baptised. Paulinus’s mission highlights the political nature of many early conversions. It is significant, however, that the conversion to Christianity was very much a ‘top-down’ process, whereby kings, queens and nobles were appealed to first, and then the message was more widely disseminated. Edwin received baptism first in AD 627, at the timber church at York, and only once the king was Christian would the message filter down to the lower strata of the population. Gregory, Augustine, Paulinus and Bede all stress that it was the decision of kings that mattered. The conversion was not about the gradual transference of religious belief among the general population, but rather a political and economic decision resting in the hands of a few.

Upon Edwin’s death in battle, his kingdom was divided, with Eanfrith succeeding him in Bernicia. Ultimately, he was replaced as king of Northumbria by the Bernician line, which had retreated into Scottish and Irish territories, where they had accepted Christianity at the hands of Celtic tutors. Edwin’s Bernician nephew (and Eanfrith’s brother) Oswald brought a different form of Christianity to the north, one that was flourishing across the borders with Scotland. Oswald won a famous victory at the Battle of Heavenfield, and immediately afterwards erected a wooden cross as a celebration of his triumph. More significantly, perhaps, Adomnán records that before the battle he had appealed in prayer for the help of St Columba. Oswald was nailing his colours to the mast. He was for the Irish Church, unlike his Deiran predecessor Edwin.

According to Bede, Oswald ruled as ‘bretwalda’, and during his reign Northumbria reached the height of its power and influence.8 Bede is very complimentary of him, and presents Oswald as the ultimate saintly king. He was responsible for granting land to St Aidan, upon which he built the monastery of Lindisfarne. In an intimate story, while Oswald and Aidan were feasting at Easter, the king was apparently moved to gift a silver plate full of food to the poor, and then ordered that the plate itself would be broken up and handed out. This led Aidan to grab hold of and bless the king’s hand, saying ‘may this hand never perish’. That his hand was subsequently enshrined and treated as a great relic was thanks not just to Oswald’s reputation as a great warrior and king, but to its being blessed by the holy Aidan.

Oswald was killed in battle against the pagan king of Mercia, Penda, in AD 642.9 He was dismembered, with his head and limbs stuck on spikes. His cult grew in popularity over the years after his death, possibly with the support of Irish saints like Aidan, though reports of miracles associated with his relics spread quickly among the population, indicating that his appeal was widespread. The head of St Oswald, decapitated by his captors during his martyrdom, is particularly interesting since it presented a problem to those Christians supporting his cult. To venerate the decapitated head of a king or hero was a pagan Celtic practice so, while his hand was blessed by a Christian bishop, his head was associated with questionable pre-Christian rituals.

Nevertheless, many different heads of St Oswald are reported, as far afield as Luxemburg, Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands. Bede reports that his head was quietly taken by his successor in Bernicia, Oswui, to Lindisfarne, where the monks surreptitiously dealt with it. The most accepted resting place for Oswald’s head now is in Durham where, after centuries of wandering across the northern landscape in search of a final resting place, the Lindisfarne monks carried it inside a wooden coffin alongside the bones of another important Northumbrian saint – Cuthbert.

Cuthbert: Converting Hearts and Minds

Poster boy of the Anglo-Saxon Church in the north, Cuthbert’s cult was finely engineered both by Bede (who wrote two official hagiographies of him) and the monks of Lindisfarne. At a time when the Irish Church was positioning itself against pagan Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Roman Christian ideas, Cuthbert was crafted as a paradigm for all that was good in the Insular tradition. The real Cuthbert is difficult to reconstruct, and appears a mass of contradictions – warrior, nobleman, bishop, hermit, politician. Yet the way his cult was contrived after his death provides a fascinating insight into the power of art and literature within the early Church, and the important role these media had as propaganda tools.

Like many of the Anglo-Saxons who converted to Christianity within the first decades of its arrival, Cuthbert was a character that had to play many parts on the political and religious stage. When he chose to leave behind the life of a warrior nobleman for the Celtic monastery of Melrose, he became an important and influential member of the fledgling Church. Under Oswald, the Northumbrian royal family had tied themselves firmly to the Celtic Christian cause, and their enthusiastic support for, and sponsorship of, the early Church was a means by which they asserted themselves over other kingdoms. Following the example of Aethelberht, whose acceptance of Christianity had ensured his position of ‘bretwalda’ within Anglo-Saxon England, Oswald – and Edwin before him – supported the Church, particularly in terms of land grants. This meant that battles against Penda and other pagan kingdoms carried a sacred element; the Northumbrians didn’t simply battle for more territory, influence or wealth, as they could argue that theirs was a holy war.

It is onto this turbulent stage that Cuthbert steps. He had grown up steeped in the pagan traditions of his ancestors, and spent a good deal of his life immersed in the power and politics of the nobility. His interest in the Church was probably a result of the ‘top-down’ nature of conversion. As a wealthy aristocrat he was able to rise to the rank of Bishop of Lindisfarne, and he took up his strategic position directly opposite the royal palace of Bamburgh. Throughout his life he was both an engaged bishop and a monastic hermit, taking himself away to Inner Farne, where he built a cell that cut off the world, with just a view of the sky. He would have survived on the eggs and flesh of sea birds, and with the elements pounding the sides of this exposed crag in the sea, a hermit’s existence must have been harsh for Cuthbert.

Although he post-dates Cuthbert slightly, Guthlac (AD 673–714) provides a useful parallel to Cuthbert, in that he too seemed to straddle two worlds. He was also an Anglo-Saxon nobleman, and he became a hermit, embracing the hostile surroundings of the Fens. Yet, between these extremes, he remained a politically and religiously active individual. As Cuthbert was Bishop of Lindisfarne and in close contact with the Northumbrian royal family, so Guthlac gave refuge to Aethelbald, the future king of Mercia. The irony of hermit life for many was that, although they retreated from human company for spiritual isolation, this made them increasingly desirable in terms of providing counsel and advice. So hermits, like anchorites, were often visited, and they retained influence in the worldly concerns they sought to escape.

Two Old English poems about Guthlac survive, indicating that he was a suitable topic for celebration not just in the traditional Latin hagiographical texts, but also in the vernacular poetic tradition more usually concerned with heroes and battles. Guthlac certainly had military roots, since he is recorded as having served in the army of the Mercian king before becoming a monk at the double monastery (containing both monks and nuns) of Repton. His life throws into sharp relief the medieval concept of the three estates, since he went from being a knight or warrior, fighting to defend the people of this world from their enemies, to being a monk and then hermit, doing battle with supernatural enemies in order to protect souls both here and in the hereafter.

Cuthbert, like Guthlac, remained a close adviser to the royal family throughout his life, even meeting with ambassadors while apparently being an isolated hermit on Inner Farne. He played the role of seer or prophet at times in terms of advising the king. In AD 685 Cuthbert descended into a seer’s mist and foretold the death of King Oswui.10 He warned the king not to go to battle, and later when walking with the queen he was struck with a vision that the king had been killed. These visions are explained as miracles, but they also served as prophetic visions, the like of which Druidic high priests and seers were subject to as part of their responsibilities towards their rulers and followers. Cuthbert was a man with one foot in the pagan past, and another in the Christian future.

The conversion to Christianity was a slow process, and saints like Cuthbert had to navigate a rocky track to direct people away from their previous beliefs and towards the new ones. We get an idea of how potent the transformation from pagan to Christian was, and how early ecclesiastics like Paulinus sought to control it on a symbolic level, when we examine a specific account from his missionary work in the north. A text known as the Anonymous Life of Saint Gregory, written around AD 713 by a monk of Whitby, shows that Paulinus didn’t always heed Gregory the Great’s guidance that the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons was to be gradual. Instead, it seems that the pagan beliefs of the Anglo-Saxons were often crushed, and at times annihilated from the landscape. The author described how Paulinus ordered a youth to shoot down a crow from a tree as proof to ‘those who were still bound … to heathenism’ that divine matters couldn’t be understood through birds.

Paulinus’s actions reveal that birds like the crow had pagan connections with divinity, and symbolised matters of life and death to some members of early seventh-century Northumbrian society. The raven was the symbolic bird of the Germanic pagan god Odinn, and Paulinus’s act of shooting the black bird was a deliberate attempt to suppress the older belief systems. It is demonstrative of how the Roman mission at times treated the native pagan beliefs they encountered. Paulinus was a powerful man, with powerful backing, tied to a powerful king. He had some success in the north, but the conversion of Anglo-Saxon England was by no means complete a full generation after Augustine arrived in Kent.

Cuthbert has a similar run-in with birds. While he was on Inner Farne he communed with the local birds.11 He was visited by two ravens, whom he had to reprimand for destroying a hay roof on one of his buildings. The ravens flew away, but returned, begging for forgiveness, with ‘half a piece of swine’s lard’, which they offered to the saint as reparation.12 When Bede came to rewrite the story of the ravens he added a speech in which Cuthbert himself angrily rebuked the birds, and he described their retreat in scathing terms, saying they ‘flew dismally away’. Furthermore, he included a moralising sentence at the end of the chapter, in which he stated that this miracle was significant, for it showed how, ‘even the proudest bird hastened to atone for the wrong that it had done to a man of God, by means of prayers, lamentations and gifts.’13 Paulinus, Cuthbert and Bede all understood the power of symbols. Today, a Christian might wear a cross around their neck to symbolise their beliefs. To a Germanic pagan the symbol of the raven carried similar potency. Challenging the pagan religion through rebranding their symbols was one way that Cuthbert sought to win over hearts and minds. But Cuthbert and his cult also harnessed the power of art to their cause.

The Power of Art

Cuthbert survives in our modern imagination so much more vividly than many other Anglo-Saxon saints because his life was thoroughly recorded by Bede, and his cult was preserved in a number of objects and texts that have survived to the present day. This enables a fuller picture of him to emerge, although the majority of textual references and material evidence related to Cuthbert had been carefully contrived posthumously. The ‘Lives’ written by Bede, the Lindisfarne Gospels and the items placed within his coffin during the various translations his body underwent, all say as much about the people writing and creating, generations after the saint’s death, as they do about Cuthbert himself.

The earliest surviving objects associated with the saint do, however, provide insights into the sort of man he may have been.14 Beginning with the pectoral cross, this small piece of jewellery indicates that Cuthbert was both a member of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and a newly converted Christian. It was not discovered until Cuthbert’s body had been reinterred, when it was found wrapped in his shroud. This suggests that he was originally buried wearing it, which is unusual, since the majority of early medieval Christian burials tended to lack grave goods.

The style of this object recalls the pagan Anglo-Saxon past, and the many brooches, buckles and adornments included in their furnished burials for the deceased to take onwards into the afterlife. The most lavish Anglo-Saxon pagan burial is Sutton Hoo, but almost all were buried with something, be it a knife, spear (for adolescent boys and men) or simple brooches. Cuthbert’s cross is clearly high status, as it is made of gold. What’s more, it resorts to the familiar technique of gold and garnet cloisonné, which is so richly attested to among the warrior class from the wealth of similar items found in the Staffordshire hoard. Nevertheless, it is clearly ecclesiastical, as suggested by the equal-armed cross shape and numerical symbolism that seems to permeate it. At its centre, the five jewels could be interpreted as the wounds of Christ, while the twelve cloisonné garnets in each of the four arms may recall the Apostles and the Evangelists.15

Cuthbert’s pectoral cross was found buried around the neck of the saint, within his coffin. It is made of gold and garnet cloisonné and was clearly well-worn. One of the arms had almost broken off and a plate was soldered onto the back to repair it. While the style is Germanic, the shape and the inclusion of a tiny Chi-Rho symbol on the loop at the top suggest it is a Christian object.

Cuthbert’s cross testifies to the symbolic transformation that high-status jewellery was undergoing in the early seventh century. From around the time Augustine’s mission arrived in Kent, jewellery in graves across the south in particular begins to change from the long-established zoomorphic interlacing metalwork characterised most exquisitely by the Sutton Hoo belt buckle. Instead, the shape of the cross begins to be articulated, first in the quartering of disc brooches, which featured four bosses surrounded by decorative spaces suggesting a cross, and then by equal-armed crosses like the stunning seventh-century survival from Wilton, Norfolk. Gold and garnet arms radiate from a gold Byzantine coin, suggesting that the owner was displaying their exotic international connections. The fact that this coin has been positioned upside down, with the cross on Calvary pointing upwards, has led to speculation that the makers of this piece were illiterate and had little experience with coinage. However, this recalls the watches of nurses, in that if it is worn around the neck on a chain, the cross will be viewed the right way up by the wearer. It was an object of personal devotion.

These objects, along with the appearance of exotic gems like amethyst and amber, as seen in the stunning Desborough necklace, suggest that tastes were changing under the influence of increased contact with the Christian Continent. They also indicate that Anglo-Saxon jewellers were having to work with a different set of symbols to suit the new religious leanings of their patrons. Cuthbert’s cross is a hybrid reaction to the broader cultural and religious changes, for while the techniques and materials used to make it accord with a far older tradition of Germanic metalworking, the shape of the cross suggests it was part of the new style of jewellery arriving with the Roman Church.

The other object known to date from around the time of Cuthbert’s death is, of course, his coffin. The oldest piece of decorated wooden carving to survive from Anglo-Saxon England, it too contains layers of symbolism that hint at the role Cuthbert played in this formative period of Anglo-Saxon history. The four sides and lid of the coffin are all incised with carved figures, each of which testifies to a different aspect of the seventh-century Church in Northumbria. On the front is one of the oldest iconic representations of the Virgin Mary and Christ child to survive outside of Rome. It recalls Byzantine images in the way both Mary and Christ stare out directly at the viewer.

The Wilton Cross, now in the British Museum, was found in Norfolk. In the centre is a solidus from the reign of Emperor Heraclius, who reigned from AD 610–41. It has been set upside down so that the viewer can see the image of the cross while wearing it.

Along one side are the twelve apostles, the most orthodox expression of the Roman Church, with Peter, the first pope, distinguished by the two keys in his hand.16 On the other side, however, is a sequence of archangels. The veneration of angels was common in the Celtic Church, but was a source of consternation for the Roman Church. Angels were seen as intermediaries between God and mankind, a role reserved for the saints and martyrs among Orthodox Christians in the seventh century. But Irish literature testifies to the popularity of angels, many of whom were named and venerated individually.

Depicting a sequence of angels in this manner indicates the influence of the Celtic monastery most closely associated with Cuthbert, Lindisfarne. Its stance on issues like the dating of Easter, the monastic tonsure and the veneration of angels were defining characteristics of the practices at this site and its satellite monasteries. By including this combination of images on Cuthbert’s coffin, the artists that created it have made a clear statement about the uniqueness of the Celtic Church: it can conform with orthodox ideas and practices, but at the same time has its own roots, traditions and traits.

One last aspect of the coffin is worth noting as yet more evidence for the transitional period in which Cuthbert lived and died, and the conciliatory role he played. On the lid is a depiction of Christ in Majesty, surrounded by the symbols of the Four Evangelists – man for Matthew, lion for Mark, calf for Luke and eagle for John. Their form is characteristic of Insular manuscript art, where the beasts are shown full-length, with books and haloes. However, something interesting has occurred with the labels next to each of the creatures. While the name of Luke is inscribed very clearly in Latin as ‘Lucas’, the names of the other three are given in runes. It seems highly unlikely that, while carving the lid of this most important of ecclesiastical coffins, the craftsman would accidentally switch scripts. Instead, it may be that this is a deliberate attempt to reflect the changing world Cuthbert inhabited.

He straddled both the secular and the spiritual, the Germanic and the Continental, the pagan and the Christian. By switching scripts the creators of the coffin are appealing to the old order and the new, and both confer a degree of protection upon the saint interred within. The whole coffin can be seen as a form of eternal prayer surrounding Cuthbert’s remains. It appeals to Christ, Mary, the saints and the angels, in both the language of the Church and of the Anglo-Saxon people. It brings different worlds together to make something harmonious, in the same way that Cuthbert himself did during his lifetime.

Cuthbert: the Lindisfarne and Stonyhurst Gospels

There is another famous object that will forever be tied to the name of St Cuthbert: the Lindisfarne Gospels.17 Although it was produced a generation after the saint died, around the year AD 700, it was designed as a cult object to venerate the monastery of Lindisfarne and its most famous bishop. At the end of the manuscript stands a colophon, added in the tenth century by Aldred, the scribe responsible for the interlinear Old English gloss. It states that the writing and illumination were the work of one man, Eadfrith. This is a feat in itself, but it seems that Eadfrith balanced his immense scribal workload with the responsibilities of being Bishop of Lindisfarne. Following the example of Cuthbert in his devotion to prayer and isolation as a hermit on Inner Farne, Eadfrith’s dedication to producing the Gospels would have been an act of extreme devotion, occupying a great deal of his time.

The process of making the Gospels would have been laborious and exhausting. Bending over curling vellum while balancing inkwells and quills, and searching for light either outside, with a portable writing desk, or inside dimly lit, smoke-filled timber halls would have required dedication and skill. The manuscript Eadfrith produced is stunning and inspired. He was driven both by a desire to create a cult object that would draw the admiration of pilgrims, and to express artistically the importance of his see at Lindisfarne to the uniquely insular character of northern English Christianity. He employed a series of original designs and carefully chosen motifs to decorate the gospels.

The Lindisfarne Gospels, London, British Library Cotton MS Nero D.IV, is recognised internationally as one of the finest illuminated manuscripts in the world. The work of one man – Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne – it is beautifully decorated throughout. The full-page illuminations include carpet pages, which combine Celtic and Anglo-Saxon motifs seamlessly.

The carpet pages that occur before each gospel reflect those in the earlier Book of Durrow, but the decoration is more meticulous and expressive. Mark’s Gospel opens with a geometric design, where an equal-armed cross can be discerned amidst the blue and red circular and linear patterns. The margins are composed of knots, while each of the four squares towards the corners contain a circular motif complete with spirals. These designs are drawn from a Celtic context, with the circular sections in particular recalling enamel panels from hanging bowls. In the centre is a very different design, however. Yellow, red and blue alternate in a series of stepped diamonds, and bring to mind the gold, garnet and glass cloisonné work on Anglo-Saxon jewellery like the Sutton Hoo shoulder clasp. Furthermore, the propensity for zoomorphic interlace witnessed in Germanic metalwork is echoed in the sections around the cross, where decorative, abstracted birds overlap and twine around one another. This page draws together artistic influences and ideas from the Celtic and the Anglo-Saxon worlds. It pays homage to the harmony that can be developed between two seemingly opposed visual traditions.

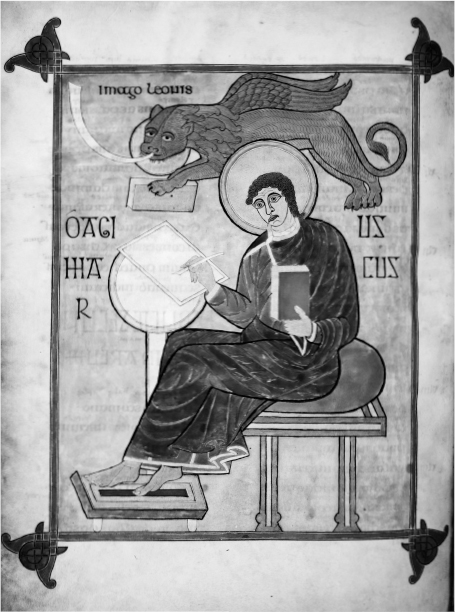

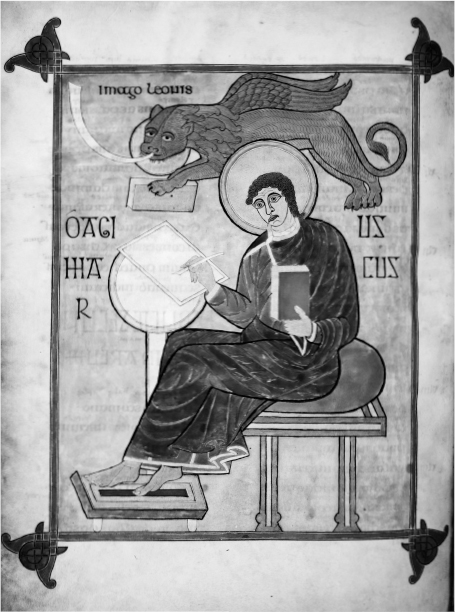

Each carpet page is followed by a decorative set of initials, which takes the idea of diminuendo presented in the Cathach of Columba and creates a stunning blend of text and image. The decoration draws the mind of the reader from contemplation and meditation on the non-figural carpet pages, through to the divinely inspired words of the Gospel itself.18 There is also an Evangelist portrait before every Gospel, depicting the author at work writing or reciting (in the case of John) their accounts. These are copied from Continental exemplars, but the style is very different.

The figures are not shown as life-like or realistic. Instead, they are abstracted, so the faces are reduced to simple shapes for the features, and the drapery becomes a series of alternating bands of colour. The treatment of the Evangelists is not down to Eadfrith being ‘bad’ at painting people. Rather, it should be seen as a deliberate attempt to avoid depicting sacred figures too realistically, perhaps due to iconoclastic attitudes abroad. By the seventh century both Judaism and Islam had predominantly chosen to avoid representing holy figures realistically for fear of producing false idols. Eadfrith follows Pope Gregory’s earlier guidance that images can help educate Christians, but he couches his figures within abstraction, the like of which anticipates the work of Picasso and Matisse. It is innovative art from an innovative place, and a benchmark of the Northumbrian Golden Age.

Yet while the Lindisfarne Gospels presents an impression of Cuthbert as a bridge between worlds, and the perfect manifestation of all that is good and worthy from both the Celtic and the Anglo-Saxon traditions, it is primarily propaganda. After his death, the cult of Cuthbert was strengthened and developed by the monastery of Lindisfarne. Laying claim to a saint was an excellent means of securing widespread admiration for their establishment, as well as a constant stream of revenue and pilgrims. The relics were important, so the monks cared for his coffin and all it contained, with one tenth-century member of the community reputedly combing Cuthbert’s hair frequently. But the other trappings of a seventh-century saint’s cult seem to have included a deluxe manuscript, as with Columba and the Cathach.

The Lindisfarne Gospels provided Eadfrith, as Bishop of Lindisfarne, with an opportunity to develop a sustained PR campaign for his monastery as it went into the eighth century. Within the vellum pages of this manuscript he created a visual style that presented Lindisfarne as an inclusive and avant-garde establishment, where all that was unique about the Church in Northumbria could be celebrated. This may indeed reflect how Cuthbert himself was perceived, but the Lindisfarne Gospels do not represent him directly. Instead, they reveal how the inheritors of his community wanted him to be seen.

In contrast, however, the small volume known as the Stonyhurst Gospel appears more intimately bound with Cuthbert himself. By turning the pages of fine vellum in this tiny pocket book it may be possible to peer over the shoulder of the saint as he read. The Victorian biblical scholar Christopher Wordsworth felt it was finer than the Lindisfarne Gospels, ‘surpassing in delicate simplicity of neatness every manuscript that I have ever seen’.19 It has the oldest preserved original leather binding in the West, and its remarkable condition is due to the care with which it was kept while among Cuthbert’s treasures at Durham Cathedral. It was wrapped inside three additional leather satchels and kept within a box for four centuries.

It is a simple, relatively unadorned copy of John’s Gospel, and in its simplicity it recalls the monastic ideal spread by the Celtic Church of wandering across the landscape with staff, bell and book, prepared to preach. Its size and apparent modesty betray the fact that, despite it being a useful pocket book, it is still a beautifully made, high-status object. The leather casing also recalls the decoration of the Lindisfarne Gospels in the way it draws together Celtic, Anglo-Saxon and Continental motifs. On the front, raised floriated scrolls sit inside a margin of knotwork, while on the back the patterns familiar from cloisonné work create a geometric incised pattern. This object, alongside the pectoral cross, coffin and Lindisfarne Gospels, tells a similar story: Cuthbert was a rallying point for the fledgling Church in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria, and a syphon for all that was good about its mixed cultural heritage.

The importance of Cuthbert and the artefacts associated with him has been recognised recently by the journey that the Lindisfarne Gospels took to Durham in 2013. Exhibited alongside the Stonyhurst Gospel, saved for the nation just a year earlier, the British Library’s most precious medieval manuscript spent three months close to the bones and relics of the saint they celebrate. Yet the true character and personality of Cuthbert have become clouded behind a screen of posthumous veneration. After his death, a deliberate set of cult objects were made to bolster his reputation and ensure a constant stream of veneration and income for the monastery of Lindisfarne. Whoever Cuthbert really was remains difficult to grasp, for in the hands of sophisticated writers, artists and spin doctors he became the perfect vehicle for sustained and energetic symbolic manipulation. A bridge between worlds, he was a saint who was moulded and crafted through the texts and artworks that came to be associated with him. But his importance at a critical moment in the evolution of the Anglo-Saxon Church cannot be underestimated. During his lifetime change was becoming the norm, and a cultural revolution was taking place. We see this most clearly in the life of one of Anglo-Saxon England’s most important female saints, Hilda of Whitby.