CHAPTER SEVEN

MUTUAL FUNDS AREN’T BULLIES

Mutual fund managers strive for perfection, worrying themselves sick and making themselves miserable in two vital realms of their existence:

- 1. Taking

- and

- 2. Selling

When it comes to taking your money, and selling you more stuff so they can take even more of your money, mutual funds are innovative and imaginative in ways that you’ll never see when it comes to managing your investments. The fund industry’s mastery of the Art of the Take makes the late-trading scandal that has obsessed regulators seem petty or even a little comical by comparison, a bit like Inspector Clouseau ticketing a car for double-parking while its occupants are robbing a bank. Like Inspector Clouseau, the fund industry has mangled the English language. Mutual funds have long embraced the credo most eloquently expressed by Clifford Odets—in a movie about people taking money—that “man was blessed with the gift of speech to conceal his thoughts.”

Take that word you keep hearing—fees. Back when late trading (that is, the decades-old practice of stale-price trading) was rediscovered and given full-dress scandal treatment by Eliot Spitzer in September 2003, critics of the fund industry fastened their gaze for several months on fees. They noted that the fund industry was cursed with excessive fees and sometimes even hidden fees. In December 2003, Eliot Spitzer forced Alliance Capital, which had been caught up in that late-trading thing, to cut its fees by $350 million. Other firms—Strong Capital Management, Janus, MFS, Invesco—were also accused of late trading and forced to cut their fees. There was some squawking, as late trading had nothing on earth to do with fees, but the protests were subdued. After all, it was natural to presume that all this fee-attacking would come to an end, so better not make a fuss. Sure enough, it was all scaled down during 2004, and the self-regulatory pyramid and Spitzer pretty much wound up their fee-cutting assault in late 2005. The whole thing had dropped out of the headlines by then, but the word fee kind of hung in the air for a while, and the media coverage indicated that there was a “fee issue” out there somewhere, and that it was being pursued and dealt with by the SEC, albeit with prodding by Spitzer and other state attorneys general.

When regulators, the media, and the fund industry talk about fees, they are referring to the 1 percent and more of actively managed mutual fund assets that are removed each year to pay for the cost of running the funds. It’s a bit like a corporate expense account with no limits except whatever are imposed by the fund manager’s own sense of ethics and fair play. In other words, no limits at all.

Now, let’s stop for a second and think about what I’ve just described. Isn’t all this stuff terrible? Shouldn’t the regulators take action? Shouldn’t it all be stopped, and now?

No.

Like Dick Grasso at the New York Stock Exchange, the fund industry is doing precisely what you are letting it do. In this instance, you function more or less in the role of the famously semicomatose NYSE board of directors. Grasso did not break any law, nor did he violate any ethical principle of which I am aware. No Sunday School, no Hebrew school, no Islamic madrassa or Hindu temple, teaches that it is improper to be paid what people are willing to pay you. Spitzer may have found some principle buried in the fine print of the New York State Consolidated Statutes, but that doesn’t give his politically motivated assault on Grasso even the slightest bit of moral justification.

Just as the NYSE paid Grasso what he wanted, you are paying the fund industry exactly what it wants. You are more powerful than Spitzer and the SEC combined. Only you can do the equivalent of sending Grasso back to his hovel in Locust Valley. Only you can withdraw assets from mutual fund companies.

If you’ve decided to stick with actively managed funds despite all the good reasons not to, it’s your job to deal with this whole fee mess. Don’t pass the buck to the SEC and the other regulators. However, you have to understand the nomenclature of fees, expenses, and such. Getting a handle on the dialect involved, what I call Mutualingo, is absolutely mandatory for those of you not willing to work the Steps to which I alluded in the last chapter.

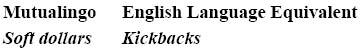

Let’s start this process of self-enlightenment by examining one phrase you may have seen tossed around now and then:

Etymology: Money used by mutual funds to overpay brokerages for commissions come straight out of your pocket—and aren’t even included in the expense ratio that is used to measure fund fees. In return for the commissions they pass on to you, the funds get office space and research they can use to pick stocks that underperform the market. The offices purchased with these dollars are usually cozy and invariably contain “soft”-cushioned furniture. Hence the phrase “soft dollars.”

As you can see, the fund industry has introduced a colorful, interesting way of expressing the concept of “kickback,” which is so plain and so, well, tacky when expressed in English. Such is the richness Mutualingo brings to our national discourse as it accomplishes its higher purpose, which is obfuscation and portfolio depletion.

Understanding how funds separate you from your money also requires you to brush up on your arithmetic. It is very hard to escape mathematics when one is examining mutual fund taking. But it is not ordinary arithmetic, more like the “fuzzy math” and “voodoo economics” that have enriched our political discourse. How much of your money are they taking? Has that amount gone up or down over the years? The answers to questions such as these depend upon who you are asking—the mutual fund industry, as represented by the Investment Company Institute, or anyone else.

The ICI backs up its answers with facts, cold hard facts, as detailed in scholarly studies it has generously underwritten and which happen to back it up 100 percent. The ICI can show you all kinds of statistics based on numbers to which it has subjected all kinds of statistical bells, whistles, and body-crevice groping. I can boil down the ICI’s well-crafted, carefully rehearsed boilerplate replies into this sentence: “Fund fees are reasonable and have been going down for many years, so everything is fine and don’t worry and don’t regulate us and go away and leave us alone.”

Logic is on the ICI’s side. The fund industry has grown quite dramatically in recent years. Equity funds, which are by far the industry’s most profitable segment, climbed from $44 billion in assets in 1980 to $4.4 trillion at the end of 2004. That’s a hundredfold increase. Industries that gain in heft can undercut their competition, force vendors to cut prices, and reduce prices for consumers. That is why you can walk into a Wal-Mart and pick up a pair of flip-flops that cost $1.88. The retailer’s economic power, its muscling of suppliers to cut prices, has resulted in charges that Wal-Mart is big, bad, and mean—the “Bully of Bentonville,” as a book by my ex-BW colleague, Tony Bianco, puts it.

Well, rest assured about this much, folks: Mutual funds are absolutely, positively not bullies. This megaindustry, so massive as to make Wal-Mart look like a lemonade stand by comparison, doesn’t gang up and kick sand in the faces of puny fund managers and fund “advisory” firms, forcing them to cut prices so that they can charge you less. Not these guys. They’re nice!

Hey, it’s not just the fund industry that is being nice. You are too, by letting them get away with charging you high fees. You’re paying too much for cruddy performance not because the fund industry is an ogre—not on this issue, Spitzer notwithstanding—but because you don’t care. It all has to do with economies of scale—the same ones that let you buy flip-flops for $1.88. Mutual funds don’t believe in economies of scale. It’s contrary to their slogan, which goes something like this: “We buy in bulk, and don’t pass the savings on to you.”

Now that funds are a multitrillion-dollar business, the resultant economies of scale suggest that they must be less costly to run per investor. If a fund has a hundred stocks in its portfolio, it shouldn’t matter whether each portfolio holding consists of a hundred shares, a thousand shares, or a million shares. Larger portfolios and larger client lists will mean higher operating costs—but not proportionally higher. Ten times the number of shares in a portfolio shouldn’t mean ten times the number of portfolio managers. These are, after all, stocks, not schoolchildren in a town with a stiff class-size restriction. Or, as one of those pesky non-ICI-compensated academic researchers once put it, “Given the industry’s explosive growth, one would expect that fund expenses on average would have plummeted.”

They should have plummeted. But they haven’t. As a matter of fact, they are actually higher than they were when the fund industry was far smaller than it is today. In September 2004, Morningstar released some figures on the expense ratios of the diversified equity funds in its database. Those are numbers that give a rough measure of the cost of running a fund in proportion to its net assets. As is usual with interesting studies that don’t make the fund industry look very good, this wasn’t exactly splattered over the headlines—the only pickup I could find was in one of the better finance Web sites, MSN Money.

Morningstar—anything but a captive of the index-fund industry or efficient-market types—examined expense ratios from the 1990s right up through 2003. Stock funds’ asset sizes wavered a little bit during that period, peaking in 1999, declining through 2002 as the markets declined, and then regaining its strength and acumen in 2004. But that expense ratio fund-skimming number took a course of its very own. The expense ratio number climbed from 1.33 percent in 1990 to 1.41 percent at its peak in 1999, at a time when you’d have thought that all that “explosive growth” would have sent fund expenses way down. The ratio increased still more through 2002, when fund assets declined. Then 2003 came around, the fund industry was healthier, asset sizes climbed—and so did fees, way up to 1.51 percent of assets, an all-time high. Morningstar tells me the 2004 number held steady at 1.50 percent.

By the way, these numbers actually understated the situation somewhat, because they included the growing number of index funds, which tend to have far lower costs than actively managed funds. Even the ICI, despite its protestations to the contrary, has generated statistics showing the average cost of operating a fund had increased sharply over the years—gaining from 0.77 percent in 1980 to 0.88 percent in 2003.

Funds haven’t defied the laws of economics. They have ignored them. Or, to put it another way, you have ignored them. You don’t pay attention to fund fees, so they are not a factor in your decision-making in buying a fund, and funds haven’t the slightest reason to cut fees to attract your business. You care about fund performance, not fund fees. The free market, which is busily at work here, obliges by socking you with fees that are unnecessarily high.

Now, that’s not to say funds don’t compete for your business. Of course they do. The fund industry boasts about that. In that revival-meeting speech in Palm Desert mentioned a couple of chapters ago, Matthew Fink of the ICI chanted in his repetitious little riff that the fund industry is competing “vigorously and fairly with one another and with other financial services and products.”

There is a lot of truth to that. However, fund-industry execs know that people don’t shop for a fund the way they shop for kitty litter or floor wax. Folks buy their funds because they think that they can get rich, beat the market, and spend their golden years lying on the beach on St. Maarten sipping melon pelicans and rubbing Bain de Soleil on the spouse. They know that most people don’t know efficient markets from Adam and still are suckered by the delusion that you can pick a fund that will make you rich. They know that most people under the age of sixty cut their teeth on Mutualingo. That’s why the investigative arm of Congress, the Government Accountability Office, observed in one of its several studies of fund fees that “mutual funds do not usually compete directly on the basis of their fees.” Other researchers who have studied the issue, notably John P. Freeman and Stewart L. Brown in their landmark 2001 study of the fund biz, reached the same conclusion—and noted that mutual funds are consistently more costly to investors than pension funds, which cater to a more savvy, price-conscious clientele and which do in fact try to undersell one another. As they put it, “price competition is largely nonexistent in the fund industry.”

Now, you might not care about any of this. You might wonder why the small fractions mentioned earlier are worth bothering about or shopping for, or worth a GAO investigation. I suppose that you might not feel right about begrudging your fund manager a point or two off your portfolio.

Well, go ahead. Begrudge.

Those little fractional expense ratio numbers don’t mean a damn thing only if you’re an in-and-out trader, like one of Charlie Kerns’s pals at Geek Securities. Fund skimming matters if you are a long-term investor, one of those “buy and forget” customers who are the supposed subject of the fund industry’s loyalty. The numbers work out like this, according to a GAO analysis: Over a twenty-year period a $10,000 investment in a fund earning 8 percent annually, with a 1 percent expense ratio, would be worth $38,122. With a 2 percent expense ratio the portfolio shrinks to $31,117—almost exactly $7,000 out of your pocket.

Now, at the risk of getting stuffy about this, I think I should identify at this point the rain that is supposed to fall on the parade whenever fund managers get their mitts on your money. It is an inconvenient, difficult-to-enforce theoretical concept called fiduciary duty. While you owe it to yourself to get the heck out of a fund that soaks you for mediocre returns, theoretically the fund management is supposed to feel a little guilty that it is soaking you and mumble to its collective self, “Gee whiz, maybe I shouldn’t do this, me being a fiduciary and all…”

The ICI actually has been quite eloquent on the subject:

Because mutual fund directors are looking out for shareholders’ interests, the law holds them to a very high standard. Directors must exercise the care that a reasonably prudent person would take with his or her own business. They are expected to exercise sound business judgment, approve policies and procedures to ensure the fund’s compliance with the federal securities laws, and undertake oversight and review of the performance of the fund’s operations as well as the operations of the fund’s service providers (with respect to the services they provide to the fund).

That should make you feel all warm and fuzzy inside, if it wasn’t a crock. Staffers of the U.S. Senate Governmental Affairs Committee looked into this whole fiduciary thing in 2004, and found that no mutual fund board had ever been held accountable for breaching its fiduciary duty to customers. That could mean that mutual fund boards have a spotless record, in which case the preceding few chapters would make excellent notepads, as they would be blank.

Actually it only seems as absurd as that until you realize the fund industry has been able to do such a great job because it doesn’t have to do a great job. The Senate committee staffers found that the Investment Company Act actually imposes a weaker standard on fund directors than you find in the already flabby state laws. What this means is that fund boards haven’t much incentive to give you a break when it comes to siphoning off your money in fees, face no real repercussions, and aren’t expected to act very strongly in your interests because the law doesn’t require it. Or, to put it more succinctly, funds can screw you and nobody will notice or care, and they’ll get away with it.

The result is a reverse of that old expression “A rising tide lifts all boats.” In this case, you have a sinking ethical tide making the entire fund industry stink to high heaven. It’s not just the rascals who have been dragged into the mutual fund morass but also the Clean Genes of the industry.

Speaking of rascals—and I use that term with affection—it was no great surprise when word emerged in early 2005 that Bear Stearns & Co. was under investigation by the SEC for alleged involvement in that late-trading mess. You expect that kind of rambunctiousness from Bear, whose very name has a wild and woolly, defecation-in-the-woods quality to it. Bear became known through the years as the Eddie Haskell of Wall Street, always trying to figure out new ways of getting the Beaver to pull a fast one on Ward Cleaver. They used to handle back-office duties for A.R. Baron and the other leading lights of the 1990s boiler rooms, and it emerged in legal proceedings that they had a ringside seat to large-scale thievery, but just kept their traps shut and did their job. That gave a charming, continental, IG Farben quality to their Eddie Haskell routine—not that they were ever found guilty of doing anything underhanded, God forbid. The law insulates Wall Street firms from wrongdoing when they handle trades for other firms, even when the other firms are run by hoodlums. And besides, they were only following orders.

If Bear Stearns is the troublemaking Eddie Haskell of Wall Street, for reasons I’ll be exploring further in Chapter 13, the American Funds Distributors fund group is the industrious Beaver who does his homework before supper and cleans his room without being asked. It would almost have been newsworthy if Bear wasn’t involved in the fund scandal. But when the American Funds group was swept up in the fund morass—now, that was a surprise. In February 2005, at about the same time Bear was getting its name dragged through the woods without anyone much caring, the NASD filed charges against American Funds. Flags went half-staff throughout Los Angeles, where this very quiet and well-reputed fund group had its headquarters. The group, third largest in the nation, with 25 million customers and $450 billion under sound and paternal management, was almost as pure and sanctified in the media as the driven snow or even the Vanguard Group, the massive index-fund behemoth that has gained near-universal adoration because of its low-cost structure (Wal-Mart should have it so good). The American Funds group was founded in 1929 and has kept pretty much to the straight and narrow ever since. Sort of.

One inkling that all might not be so clean and tidy at American Funds came in June 2004. A gent by the name of John C. Carter, who lived in San Dimas, California, put some comments on the SEC Web site concerning his beef against Smith Barney, which he had accused in an arbitration case of not properly handling his retirement accounts. According to Carter, Smith Barney had a strange fixation on the funds of one, and only one, fund group—the Clean Gene, early-homework-doing, room-cleaning, well-reputed American Funds group. Carter said as follows: “We believe that our broker recommended only American Funds based on a commission that she would receive from the Capital Group parent company.”*

It should be noted that Mr. Carter was not a realistic man. In fact, he appeared to be almost Utopian in his worldview, judging from his suggestion that “it would be very helpful to unsuspecting small investors if the SEC would require brokers working on commission, to have the word Sales in their titles such as Sales Advisor or Commissioned Sales Broker. Vague titles such as VP Investments or Senior Advisor only mislead the individual investor.” Even if you disregard such fantasies, you have to admit that Mr. Carter’s complaint was disturbing. It indicated pretty clearly that the American Funds group wasn’t doing all that great a job at its fiduciary duty. That impression was substantiated somewhat eight months later, on February 16, 2005, when the NASD filed its complaint against American Funds.

The NASD said that American Funds “entered into yearly sponsorship arrangements with approximately 50 NASD member firms that were the top sellers of American Funds.” It said that “as part of these sponsorship arrangements [American Funds] arranged for approximately $100 million of brokerage commissions generated by American Funds portfolio trades to be directed to these top-selling retailers of American Funds to reward past sales and to encourage future sales.”

Doesn’t that seem to be just a bit of a conflict of interest for those “approximately 50” unnamed NASD member firms? As for the American Funds group—well, if there’s any truth at all to these allegations, I’d say that just a touch of the Bear Stearns–Eddie Haskell quality, that same charming all-American mischievous desire to skin the investor, had rubbed off on the nerds at American Funds.

The NASD did not identify the “approximately 50” brokerages (they could have gotten a precise count, don’t you think?) that enjoyed these sponsorship arrangements. But the Carter beef would seem to indicate that Smith Barney—a fun-loving bunch of fellows fond of wine, women, and more women, according to various lawsuits over the years—was one of those anonymous “approximately 50.” “We have since discovered,” Carter told the SEC, “that Smith Barney receives additional compensation from Capital Group as a top, if not the top, sales generating organization. This conflict of interest cannot be in the best interests of the small investor who, in good faith, may have entrusted their life savings to such a broker.”

Mr. Carter was being entirely unfair to Smith Barney and American Funds. He may not have known it, but pretty much every major brokerage firm on Wall Street also sops its bread in mutual fund gravy. That has been an open secret for years, but the first firm to actually get a “tsk-tsk” from regulators on that issue was Morgan Stanley. In November 2003, Morgan settled with the SEC and NASD for not telling its customers about revenue-sharing arrangements—Morgan used the pretty phrase “Partners Program”—that it neither admitted nor denied having with sixteen fund companies, including American Funds. Morgan wound up paying $50 million, which is about what it spends on metal polish for the executive silverware. Still, it’s not the money—or, in this case, the chump change—that was the problem. It was the hurt, the sense of betrayal. After all, we’re talking about family here! Evidently all those “financial advisors” in the “unusually devoted to your dreams” TV commercials had a deep, dark secret while attending football games, lying on the beach, and being part of the family.

Taking payments for selling funds of favored fund companies is not a no-no in itself—at least, not according to the moral compass of the self-regulatory pyramid, the mutual fund industry, and the financial press, none of which have ever come out and explicitly condemned the practice. From the standpoint of Sunday School morality, or the workaday ethics of any industry other than Wall Street, it would be something else entirely. As a conservative Republican senator from Illinois, Peter G. Fitzgerald, put it, “If a publicly traded corporation, not a mutual fund, went to brokerage houses and said: We will give you a dollar for every share of our stock that you sell, that would be an outrageous fraud on the public.” As a matter of fact, he pointed out, “In Chicago they call that a kickback.”

The regulatory response to that is, “Kickback, shmickback.” Revenue-sharing * kickback arrangements emerge on the radar screen only when the feds encounter a Cool Hand Luke brokerage or mutual fund. They’ll reach for a whip only when they can say, “What we have here is a failure to communicate.”

Let no man say that Smith Barney was guilty of a failure to communicate in its dealing with Mr. Carter’s account—that is, not lately. In March 2005, the Citigroup subsidiary settled SEC and NASD charges that it had failed to communicate properly all that revenue-sharing stuff with customers in 2002 and 2003. The firm managed to keep in the SEC’s and NASD’s good graces since then by communicating—telling all the folks about its kickbacks. In June 2004 and again in June 2005, the firm disclosed on its Web site that “for each fund family we offer, we seek to collect a mutual fund support fee, or what has come to be called a revenue-sharing payment. These revenue-sharing payments are in addition to the sales charges, annual service fees (referred to as ‘12b-1 fees’), applicable redemption fees and deferred sales charges, and other fees and expenses disclosed in a fund’s prospectus fee table.” All this revenue sharing comes to $2 billion a year for the fund industry as a whole, according to the SEC.

Though the ICI likes to point out that since the payments come from the supposedly independent advisors, investors aren’t directly socked for the fees, what that ignores is that, as an otherwise vapid SEC study has pointed out, the kickbacks are factored into the cost of hiring all those brilliant people to run the funds. (If they weren’t, the fund companies and their various affiliates and advisory companies would not be profitable—and that would never do.)

Smith Barney listed two classes of funds that engaged in those fee-sharing arrangements—a list of 42 funds on the left and 29 on the right in 2004, and 37 on the left and 25 on the right in 2005. The longer list consisted of the funds that received “access to our branch offices and Financial Consultants for marketing and other promotional efforts.” In other words, what is known as shelf space at your local A & P. These were listed because of, “among other things, their product offerings and demand among our Financial Consultants and clients”—as if these funds were actually bought and not rammed down their clients’ throats. The list on the right didn’t get branch access.

The funds on the longer list were popular—and how. According to Smith Barney, they accounted for 96.2 percent of mutual fund sales in 2003 and 94.4 percent in 2004. It’s quite a list. It was such a distinguished list that I thought it might be nice to duplicate the 2005 list here for you. According to Smith Barney, this list is rank-ordered, with the biggest-paying firms on top:

Just a few trillion bucks under management here. The other group listed by Smith Barney, the twenty-five fund groups that were not so popular, were not broken out in 2005, but in 2004 they accounted for another 2.3 percent of sales. In 2003 (there was no aggregate number given for 2004), 99.2 percent of mutual fund sales by Smith Barney consisted of funds that paid extra for the privilege.

Funds don’t have to compete when they’re paying kickbacks. Rampant revenue-sharing kickback arrangements pretty much turn this whole issue of price competition into the joke that it truly is. The whole purpose of paying kickbacks is to avoid price competition.

So, back to our original question: Are you going to surrender to the Higher Power of the stock market and put your money in index funds, or are you going to give your money to actively managed funds that pay to be sold to you?

Before you mull that over, it might be worthwhile to pause for a moment and consider the phenomenon that you have just witnessed.

Over the past few years, various Wall Street firms and mutual fund groups have found themselves having to be shamed, and to pay small penalties for various offenses concerning both the Mutual Fund Scandals and all manner of other Wall Street unpleasantness. Many, if not most, could have spared themselves all the pain and humiliation if they had just put a few words in the appropriate document or on their Web sites—just as Smith Barney in the preceding pages—or in one of their mailings that nobody reads, so as to satisfy their quasi-confessional disclosure obligations.

It doesn’t matter one bit that nobody reads that stuff. Fund disclosures, like corporate filings generally, are a kind of self-absolving confession. Once set down on paper, any nastiness is considered disclosed to the whole wide world. That’s usually sufficient to fend off any accusations involving fraud or over-charges. No concealment, voilà! No fraud.

Imagine what a great world it would be if you could pull off that kind of thing yourself. Just write down on a piece of paper that you aren’t particularly competent or honest, leave it somewhere in your supervisor’s office, and it will keep you from being fired for incompetence or dishonesty. Or put it in a blog nobody reads. You’ll have just tapped into the secret to a full and happy life, filled with mediocrity and riches, Wall Street–style.

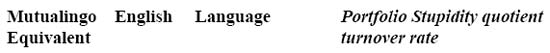

One of the things mutual funds are not happy to disclose, in those statements you never read, is how much they pay in commissions for all the buying and selling of the stocks and bonds in their portfolios. This number is not reflected in the expense ratio that is commonly used to quantify mutual fees. Commissions are not something mutual fund companies like to talk about. That’s because when it comes to trading, fund companies are the Wall Street equivalent of an oil baroness or Third World dictator’s wife on a shopping spree in Paris. Imelda Marcos stocked her closets with shoes; your mutual fund stocks your portfolio with trades.

The more a fund trades, the higher its portfolio turnover rate. If you are one of the tiny sliver of fund customers who actually read all those boring mutual fund mailings, you’ll find this term—“portfolio turnover rate.” A 50 percent turnover rate means that half the assets of the fund changes hands over a particular period of time. It’s not unusual for funds to have annual turnover rates of 100 percent or higher. But what does that mean for you? This brings us to the last Mutualingo concept we’ll be studying in this chapter:

The problem with all of this love of trading is (1) the more they trade the more it costs, and they pass on the commissions to you; and (2) they are lousy traders. Trading is not only costly, it is stupid. The more they trade, the worse they perform.

That should really come as no great surprise, when you take into consideration that 90 percent of mutual funds don’t beat the market over the long term. But this is more than just a good surmise. There is actually some reasonably good data on the subject. In 2001, a trio of researchers from three universities, John M. R. Chalmers, Roger M. Edelen, and Gregory B. Kadlec, produced a study on the costs and effectiveness of mutual fund trading. The Chalmers-Edelen-Kadlec team picked 132 funds at random, examined their trading data, ran the numbers through the usual statistical Mixmaster, and found “a strong negative relation between fund returns and trading expenses.” (The assumption being that if they were good traders, and not just doing it for fun, it would have a positive impact on performance.) As a matter of fact, the researchers said, “we cannot reject the hypothesis that every dollar spent on trading expenses results in a dollar reduction in fund value.” Money down the toilet! Yessir, your actively managed mutual fund in action.

Other studies have shown that it’s not just trading dollars that are wasted, but every buck spent on running mutual fund portfolios, from commissions to manager salaries to the cost of the urinal mints in the men’s room. Researchers have proven time and again that the cost of running a mutual fund portfolio is not justified. It is a waste of money more often than not. Chalmers-Edelen-Kadlec also found that funds “have incentives to churn their portfolios even when no value maximizing trades are found.” Fund-compensation arrangements, they observed, don’t penalize fund managers who trade incompetently or wastefully—still more evidence that this whole “fiduciary duty” concept is just a lot of kidding around by the fund industry.

At this point you may be wondering about all the fund watchdogs you’ve been reading about—the regulators and government officials who actually do seem to penalize fund managers and fund companies, and do indeed appear to take seriously this fiduciary stuff. They are on the case, and are working hard, or so the media has reported.

When an SEC factotum named Paul F. Roye announced in February 2005 that he was stepping down as chief of investment company regulation, the financial press used the opportunity to review all that Roye and the SEC had been doing on mutual funds, and the general consensus was that the regulators had been doing a lot, and were going to do a lot more. The MarketWatch Web site expressed the zeitgeist best as it described the kind of tough hombre needed to fill Roye’s shoes: “Wanted: Tough, change-minded public servant to take over as the nation’s top mutual-fund regulator. Must be able to handle controversy and heated challenges.”

Change-minded? You bet. The SEC is proposing, and adopting, a bunch of changes. Let’s see what they are.