Without realizing it at the time, I presided over what was probably the last hurrah for the fearless leaders of telecom. My conference coincided perfectly with the absolute zenith of the bull market. There was a giddy hysteria to it that at the time was thrilling and contagious; looking back, it seems pathetic. Everyone there was making money hand over fist, from the executives whose stock options were soaring to the bankers who were awash in deal fees to the institutional investors who, armed with that extra edge, were getting to IPOs and M&A announcements just a little bit sooner than the rest of the world.

THE NEW MILLENNIUM DAWNED with the kind of frenzied excess that had come to seem normal. In retrospect, it was really the dancing-on-graves-with-fingers-crossed kind of mania that happens when everyone knows in their heart that it just can’t last. The first big telecom event of the year was Salomon Smith Barney’s annual Palm Springs telecom and media conference in January, hosted by Jack Grubman. I wasn’t invited, of course, but I paid a lot of attention to the wires, since some news was likely to break during the event.

Like my conference, it was a star-studded gathering, a who’s who of telecom attended by many of the industry’s top executives. Our two events, held just two months apart, were the two best-attended conferences for telecom investors, and we each tried to put on the most dynamic show possible. Jack’s event, because it took place at a golf resort, was more casual in style, while ours, in New York, was a bit more formal and urbane. As always, we were competing—this time, to attract the most influential speakers and attendees, who would, hopefully, bring to light some important new information.

In Palm Springs, Bernie Ebbers and Scott Sullivan of WorldCom were the most popular speakers, and rightfully so, since the company’s stock continued to soar, having nearly quintupled in the previous four years and become the NASDAQ’s most successful stock of the decade. The gym teacher cowboy from Canada and the numbers whiz from upstate New York were the dream team of telecom who had transformed the industry like no others. Way back in 1995, the company had hired Michael Jordan as a spokesperson. And now, it seemed, WorldCom had become the Michael Jordan of its own sector, outhustling, outthinking, and out–wheeling and dealing its plodding competitors. (In 2005, Michael Jordan would sue the company, claiming that the company owed him $8 million.1)

But what Bernie and Scott were saying on this day, though diffused in a fluffy cloud of optimism, got some tongues wagging. Clients called to tell me that one of their slides showed a revenue growth range of 13.5–15.5 percent for the year 2000. It was a terrific range to have, but it wasn’t quite the 14.5–15.5 percent range that had been cited in their conference call a few months earlier, in October.

A full percentage point may not seem like a lot, but it can have a major effect on investor perceptions and, if the downward trend continues, on a company’s stock price. Conference attendees buzzed. Were Bernie and Scott saying that the real number was only 13.5 percent now and the Wall Street consensus of 14.5–15.5 percent was too high? Were they just hedging in case the economy slowed? Or did they know something we didn’t? Some of the biggest WorldCom bulls actually wondered whether the presentation simply had a typo. People asked Scott what it all meant, but he simply said that that was the range, and not to read any more into the top end of the range than the low end. That day, WorldCom shares fell 11 percent, from $49.94 to $44.44. It sure looked as if the attendees at Salomon’s conference were reading more into the low end.

The stock settled down after a few days, but toward the end of January it began to slide again, falling about 25 cents a day or so. I watched with concern, as I still had a Strong Buy, or “1,” rating on it, the top rating in CSFB’s system, and finally called some of my clients to see if they knew anything. One of them told me that he’d spoken to Jack, who had said he’d talked to Scott and that 13–15 percent, not 13.5–15.5 percent, was actually more accurate, with the lower end more likely than the higher end.

We all knew better than to believe everything Jack said by now, but when it came to WorldCom, it was foolish to ignore him: he was better connected with this company than anyone, and he’d certainly come up with critical information before. If this information was true, however, it was a terrifying number for anyone who owned WorldCom, since if the revenue numbers came out that low, the stock would surely plummet.

This was particularly true for a growth company like WorldCom with a suddenly slowing growth rate. Wall Street is a game of expectations: when expectations are not met, the market usually reacts swiftly and brutally. I was worried, but I didn’t want to change anything until I had more than hearsay backing me up.

At the end of January 2000, I hosted a luncheon for Ivan Seidenberg, CEO of Bell Atlantic, and invited some money managers from the country’s biggest financial institutions. This was one of those perks for the most favored—or most powerful—clients; an intimate group of 20 people lunching with a top executive. I held about eight of these each year, and almost always scheduled them in the elegant Library Room on the second floor of the St. Regis Hotel. The St. Regis, located in midtown Manhattan, was one of New York’s swankiest hotels, a place where the ornate Louis XIV–decorated rooms went for around $575 a night.

As my handpicked group of powerful investors chatted before sitting down, I heard more about Jack’s claim that he’d talked to Scott Sullivan. The irony was that Jack was now so powerful that these rumors took on a life of their own. He had succeeded in making everyone believe that his relationship with WorldCom was so tight that even if what he said wasn’t true, few would doubt him. Anything he said was now as important, if not more important, than what Bernie or Scott said about WorldCom. I had no idea what was correct; all I knew was that the stock was dropping.

After lunch I asked Ehud Gelblum and Ido Cohen, an extremely bright young analyst I had hired shortly after my move to CSFB, to call Blair Bingham, one of WorldCom’s investor relations guys, and press him for some more information. I showed Ivan out and returned to the St. Regis’s Library Room to hear Blair, on speakerphone, reiterating that the range remained 13.5–15.5 percent.

I jumped in. “Hi, Blair, this is Dan,” I said. “Here’s our dilemma. We’re recommending your stock with a Strong Buy rating. We’re getting a lot of questions lately, because apparently Jack is saying that the revenue forecast should be closer to the lower end of that range, based on a recent conversation he had with Scott.”

Blair dismissed my question right away. “I don’t know anything about such a conversation, Dan,” he said, “and I don’t know what Jack is saying, but it doesn’t matter anyway. Bernie told everyone in Palm Springs that the range was 13.5–15.5 percent and one shouldn’t read anything more into the lower end than the higher end.”

“I hear you,” I interrupted, “but you’ve got a problem. I don’t know who said what to whom, but I do know you guys have given Jack a very disproportionate voice on your stock. If he says revenues will grow 13 percent and you deny it, the vast majority of investors are going to either believe the 13 percent or live in fear of it. No one is going to believe you.”

I asked him to get Scott Sullivan, the CFO, on the phone. “Otherwise,” I threatened, “I’m going to have to cut our revenue forecast this afternoon.” I was playing hardball, but I needed some answers here.

“Well, uh, I’ll try,” Blair said doubtfully, “but I don’t know if I can find him…”

“We’ll just wait here on the line, Blair,” I said. “Thanks.”

Amazingly, Scott came on the line within five minutes.

“Hey, Dan, what’s up?” Scott began nonchalantly. No matter what was going on, Scott was exactly the same. He spoke in a monotone, dressed and acted conservatively, and never appeared to get excited when the stock was soaring or distressed when it wasn’t. He was as steady as Qwest’s Joe Nacchio was volatile.

“Just trying to get a read on your outlook for revenues and struggling with Jack’s banter that it’s going to be lower than you’ve indicated,” I said.

“What do you mean?” asked Scott.

“Come on, Scott,” I said. “You know how this works. You, or perhaps Bernie, told the Salomon conference that you were anticipating revenues to grow 13.5–15.5 percent this year. But then I’m hearing from some buy-siders that Jack cited a private conversation with you in which you endorsed the lower end of a 13–15 percent range.”

Scott denied it. “I haven’t talked to him since his conference,” he said.

“If you haven’t talked to him,” I said, “then you need to say that publicly. Right now, your largest holders are believing him, as he has quite a record of having far better information than the rest of us,” I continued, and then added for effect, “Even those of us who have been bullish on your stock.”

“I’m telling you now,” Scott said, exasperated. “Why don’t you pass this on to your clients?”

“It won’t do much good, Scott. You have created your own monster here,” I said, referring to Jack.

Scott denied it again.

Author as college student studying Middle East politics: Here shown touring ruins of Troy (Ephesus, Turkey), Summer 1973.

Our home and daughters in Potomac, MD, 1988: “Ed took one look at the house and almost started laughing. ‘You ought to come to Wall Street and hit the big time,’ he said.”

Bert C. Roberts, Chairman and CEO of MCI Communications announcing MCI’s merger with British Telecom, the largest cross-border merger ever at the time. The deal fell apart but Bernie Ebbers of WorldCom stepped in, taking over MCI and sealing Bert’s and MCI’s fate November 3, 1986. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Author (right) and Ed Greenberg, Morgan Stanley’s telecom analyst, with chauffeur and Bentley hired by Morgan Stanley to shuttle us between meetings with European investors. November 1988. Six months later, Ed convinced me to take over his job at Morgan Stanley.(Jim Hayter)

Author (left), Dan Akerson, MCI’s CFO (middle), and Jim Hayter, MCI’s Director of Investor Relations, in Zurich, Switzerland, taking a break between meetings with Swiss institutional investors. November 1988. (Jim Hayter)

John Mack, President of Morgan Stanley, CEO of CSFB and now CEO of Morgan Stanley. “Sure John,” I said. “How can I say no to an invitation from John Mack?” (AP/Wide World Photos)

Arthur Levitt, SEC Chairman 1993-2001. Levitt may have made speeches about analyst conflicts of interest but, on his watch, the SEC issued the “No Action Letter” that propelled analyst conflicts to new heights. (AP/Wide World Photos)

“The Siskel & Ebert of Telecom Investing.” The New York Times Sunday Money & Business section featured a front page article contrasting Jack Grubman’s and my styles and opinions. February 4, 1996.(New York Times)

“Jack Grubman and Dan Reingold say they like each other. You’d never know it from the hand grenades they toss back and forth.” (Mark Landler, New York Times)

Evangelist for the Internet: Jim Crowe, CEO, Level 3 and (previously) CEO, Metropolitan Fiber Systems (MFS). Jim tried to turn me into an Internet believer but I just didn’t “get it.” (AP/Wide World Photos)

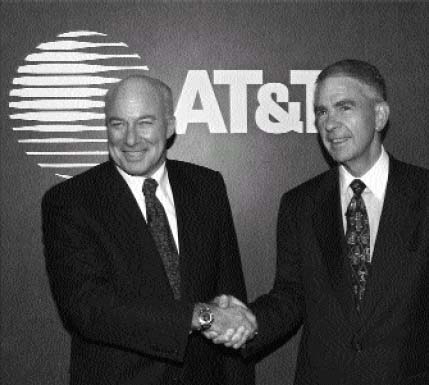

A savior’s arrival? Mike Armstrong is welcomed by Bob Allen, AT&T’s outgoing Chairman and CEO. October 20, 1997.(AP/Wide World Photos)

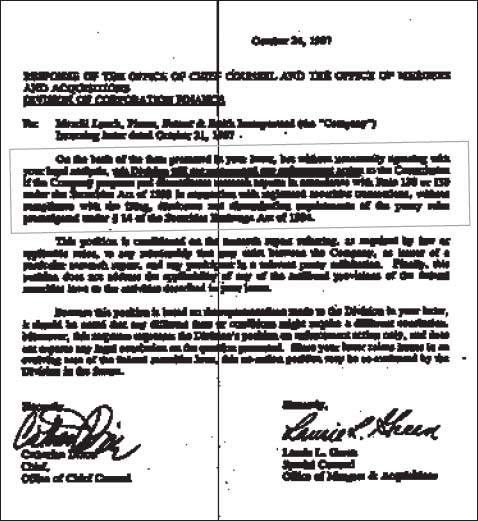

The SEC’s “No Action Letter” that propelled analyst conflicts to new heights. October 24, 1997.

SBC CEO Ed Whitacre and Ameritech CEO Dick Notebaert announcing the sale of Ameritech to SBC for $62 billion. My firm, Merrill, tried desperately for a role but failed and so did I. May 11, 1998. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Mike Armstrong, CEO of AT&T, and John Malone, CEO of Tele-Communications Inc., taking questions after announcing AT&T’s $32 billion acquisition of Malone’s cable TV company. Armstrong had dreams of bundling phone, internet, and entertainment services over cable TV lines. June 24, 1998.(AP/Wide World Photos)

Like blood brothers, Qwest CEO Joe Nacchio and US West CEO Sol Trujillo yuk it up at the press conference announcing the merger of their two companies. Two days earlier, Nacchio threatened to back out of any deal that required him to share the CEO role with Trujillo. July 19, 1999. (AP/Wide World Photos)

One amazing leak: On October 5, 1999, Sprint CEO Bill Esrey (left) and WorldCom’s Bernie Ebbers announced the merger of their two companies. But 27 days earlier, the deal and its exact price had been leaked. The stocks’ values changed by a total of $14 billion during that period.(AP/Wide World Photos)

Merrill Lynch CEO David Komansky was President and then CEO during my nearly seven years at Merrill. June 1,1999. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Joe Nacchio, CEO of Qwest, talking up his company and the Internet. Qwest would later admit to inflating its revenues by $3 billion.(AP/Wide World Photos)

AT&T Wireless IPO: CSFB (my firm) and Salomon Smith Barney (Grubman’s firm) competed hard for a lead role in the $10 billion AT&T Wireless IPO, the largest in US history. AT&T CEO Mike Armstrong (left), AT&T Wireless CEO John Zeglis (middle), and New York Stock Exchange Chairman Dick Grasso, celebrating the initiation of NYSE trading. April 27, 2000. (AP/Wide World Photos)

My arb call from a mountaintop: waiting to speak on Qwest/Deutsche Telekom/US West rumors via CSFB’s squawk box from Vail, Colorado. The rumors created panic trading and huge opportunities. March 2, 2000. (Howard Jacobs)

Members of my research team on a ski outing with clients at Telluride, Colorado. (From left) Julia Belladonna, Bill Newbury of TIAA-CREF, Ehud Gelblum, author, and Ido Cohen. January 2001. (Jeff Jacobs)

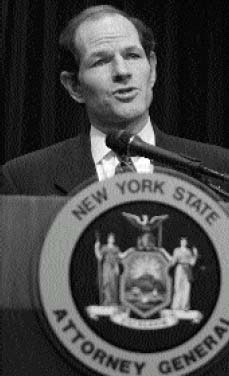

Eliot Spitzer, New York State Attorney General, announcing his investigation into conflicts of interest in Wall Street research. Spitzer settled most cases, leaving many questions unanswered and misdeeds unpunished. April 8, 2002.(AP/Wide World Photos)

Congressional hearings on WorldCom: On July 8, 2002, just two weeks after the fraud was discovered, the House Financial Services Committee interrogated four key witnesses. (From left) Melvin Dick, Arthur Andersen; Bernie Ebbers, former WorldCom CEO; Scott Sullivan, former CFO; and Jack Grubman, Salomon Smith Barney telecom analyst. (AP/Wide World Photos)

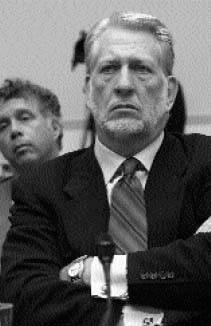

Ebbers, silent but stoic at the Congressional hearings, with his high-powered defense attorney, Reid Weingarten (left). July 8, 2002. (AP/Wide World Photos)

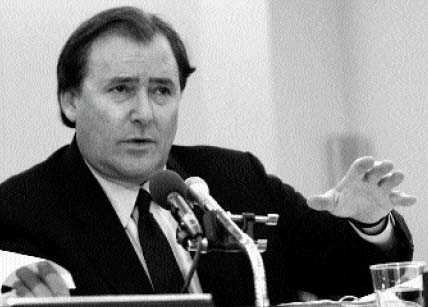

Jack Grubman in front of the House Financial Services Committee: Asked whether he knew about special IPO allocations made to various telecom executives, Grubman waffled “I’m not saying no, I’m not saying yes. I just can’t recall.” July 8, 2002. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Scott Sullivan, former WorldCom CFO, in front of the House Financial Services Committee. July 8, 2002. Sullivan’s fraudulent adjustments to WorldCom’s books totaled a mind-boggling $11 billion. He pleaded guilty to numerous criminal charges yet was a highly effective witness against Ebbers.(AP/Wide World Photos)

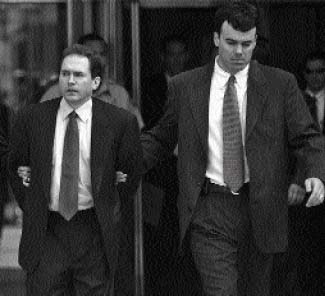

Handcuffed Scott Sullivan (left) is led by federal agents from the posh New York City Hotel Elysée at 7 a.m. on the morning of August 1, 2002. He was charged with seven counts of securities fraud, conspiracy and filing false statements and was later sentenced to five years in federal prison. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Global Crossing executives take oath before testifying before the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee: (from right) Chairman Gary Winnick, CFO Dan Cohrs, Executive Vice President of Finance Joe Perrone, President David Walsh, and former counsel Jim Gorton. October 1, 2002.(AP/Wide World Photos)

Global Crossing Chairman Gary Winnick offered $25 million of his own money to cover losses in his employees’ 401(k) accounts, a pittance compared to their losses and his gains. October 1, 2002.(AP/Wide World Photos)

Frank Quattrone, technology banker extraordinaire, exiting Manhattan federal court. April 23, 2003. A jury found him guilty of obstruction of justice and he was sentenced to 18 months in prison. He is appealing. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Bernie Ebbers, handcuffed and escorted by federal agents, after being charged with securities fraud, conspiracy to commit securities fraud, and making false statements to the Securities and Exchange Commission. March 3, 2004. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Bernie Ebbers and his tearful wife, Kristie, leaving federal court after a jury found him guilty on all nine counts. He was later sentenced to 25 years in federal prison. (New York Post/RexUSA)

“Let’s be real,” I interjected. “The only way to avoid this in the future is to stop giving him special information as it just enhances his market power. Right now that’s working against you and I’m powerless to help.”

“Dan,” Scott insisted, “I assure you that stuff is not going on anymore.” Not going on anymore?

Well, if I’d ever needed any justification for all those sleepless nights, I now had it. It seemed Scott was admitting what I’d suspected for a long time: Jack was getting better information than the rest of us. In one sense, I felt vindicated. The conversation confirmed all of my worst suspicions about the Jack-WorldCom relationship.

On the other hand, I also felt sick. The way this business worked was beginning to disgust me. No matter how much analysis the rest of us did and no matter how much we knew about the telecom industry, we’d always know less about WorldCom than Jack Grubman. He not only knew more than the rest of us, but sometimes seemed to know more than the company itself.

“That’s good,” I said sarcastically, and Scott said he had to take another call. We signed off.

“What’s the matter with these guys?” Ido asked. “Why would they voluntarily play with the devil?”

“Get it right, Ido,” I said. “It’s the devil playing with the devil. I guess that’s why they get along so well.”

I hate what this job has become, I thought. Everything is rumor, leaks, and guidance. Is anyone doing primary research anymore? Am I? Not really. I’m too busy keeping up with all these whispers and denials, because that’s what moves stocks. I was spending most of my time trying to track down who said what to whom when I should have been out there talking to competitors, customers, and suppliers, kicking the tires of companies and figuring out what was really going on. This job was now less about analysis and more than ever about whom you knew. I was embarrassed, both for how my own work had become increasingly superficial and for the investment research profession overall. I wondered if I could make it through another three years.

A few weeks later, in early March 2000, the mouth of my dear old “friend” Joe Nacchio got him in trouble again—and forced me into another one of those seat-of-the-pants decisions that I hated so much. I didn’t know it then, but it would turn out to be one of the last good calls of my career.

I was skiing at Vail’s new-terrain, just-opened Blue Sky Basin with Jeff Jacobs, my friend and stockbroker from Merrill, and his father, Howard. It was a warm, sunny day, and we had just finished an unbelievable run through deep powder and were on the chairlift when my cell phone rang. I wanted to ignore it and get back to enjoying the Colorado sun and powder, but finally I pulled the phone from my jacket and saw that it was Julia Belladonna, one of my young team members who had come over with me from Merrill and worked with me on the Baby Bells.

“Hi,” I said. “Just don’t tell me Bernie’s canceling [his commitment to give the keynote at my conference next week].” Julia, a serious, unflappable sort who had worked as a paralegal before deciding she wanted to break into equity research, was normally very calm, but there was a real edge to her voice. The cell signal was weak and it was hard to hear her, so I asked her to speak louder. Yelling, her words came through this time. “US West is getting hammered, Dan. All hell is breaking loose. The salespeople want you and want you now!”

“Oh, great,” I responded. “What’s going on?”

“There is some story flying around the Street,” she said, “saying Qwest has been approached by a foreign company and Qwest may break off its deal to acquire US West.”

The previous July, at the end of the bidding war between Global Crossing and Qwest for Frontier and US West, Qwest had agreed to buy US West, but the deal hadn’t yet been finalized. The speculation apparently stemmed from a USA Today story that morning, March 1, 2000, citing people close to both Deutsche Telekom and Qwest confirming that the two telecom giants were in negotiations.2 No one knew for sure whether this meant that US West would be included in such a deal or not. Yet the rumor seemed to be that Qwest would abandon US West at the altar, preferring to sell itself to Deutsche Telekom for a big profit.

If one looked at it from Qwest CEO Joe Nacchio’s perspective, this made tremendous sense: Joe would receive over $700 million in stock if Qwest were bought out by another company like Deutsche Telekom. All of his shares and options would vest immediately. Buy-siders later told me that Joe was fueling the fire by critizing US West’s management at the same time that he was supposedly in negotiations with Deutsche Telekom.

Just as had happened two years earlier with the BT-MCI deal, I didn’t know whether Qwest could, under the terms of its merger contract with US West, actually back out of the deal. As good as Vail’s sunlight and visibility were from a skier’s perspective, they didn’t help me as an analyst. I simply couldn’t be sure from the top of a mountain. In the meantime, US West shares were down big time, falling 11 percent that morning as the story spread, while Qwest shares had surged 26.5 percent on the takeover speculation.

This meant that US West was now trading about 40 percent below what Qwest had committed to pay in the deal, reflecting the market’s fear that the US West–Qwest merger was dead in the water. People who owned US West were bailing out as rapidly as they could, while investors were piling into Qwest, thinking a rich price was coming soon from Deutsche Telekom. Much of this was fueled by arbitrageurs. Arbitrageurs, or “arbs,” are the traders who make a living by betting on whether a given deal will happen or not and trying to take advantage of the difference between the original price offered for a company at the time a deal is announced and where it’s currently trading, also called the “arb spread.”

Usually, arb spreads run between 5 percent and 15 percent on mergers with six months or less to go until the deal closes. This time, the spread was huge, partly because of the uncertainty of the situation, but also because three years earlier, the arb community had lost so much money in the BT-MCI debacle that it had turned gun-shy on large telecom mergers. As a result, arbs were desperately unloading their US West shares, panicked that they would get burned as badly as they had been by MCI.

With all of this information swirling around the Street, I had to make a call quickly. My new sales force at CSFB, which had not yet seen me handle a crisis, and my clients were clamoring for instant advice, which meant I didn’t have time to read the merger agreement or to call Joe Nacchio and Sol Trujillo or a few M&A lawyers to get some perspective, as I normally would. I asked Julia to call me back in 15 minutes, which would be 2:00 PM New York time and noon in Vail, and to arrange for me to speak into CSFB’s “squawk box,” which would broadcast my comments to CSFB’s salespeople around the world. This was the quickest way to get my views out to my clients, not to mention the best way to get my phone to stop ringing so I could get back to skiing. The last thing I wanted was to have another vacation ruined by a merger falling apart, especially on this beautiful mountain on this beautiful March day.

I hung up and got off the lift, almost dropping my phone in the snow. I quickly told Jeff and Howard what was going on. I asked them if they wanted to go on without me, but Jeff—always the stock junkie—said he wanted to hear what I had to say. Thinking frantically, I decided that if Deutsche Telekom did buy Qwest, it would be foolish to buy it without US West, both to avoid years of litigation and to get US West’s local telephone assets—its “last mile” connections to customers—which I considered so valuable. I didn’t have any facts or experts to back up what was essentially a gut feeling, and I wasn’t going to acquire any in the next 15 minutes.

So just as I had done that night in Tuscany, I made a snap judgment, a potentially reckless one, this time from a Colorado mountain. We skied down until I spotted a small ridge in the sunlight. I looked at my phone to check the cell signal and it was strong enough. I sat down in the snow and called Julia, who connected me to CSFB’s squawk box.

I explained my belief that the Qwest–US West merger would be very tough to undo, and discussed the widening arb spread. “My call is to buy US West and short Qwest shares, and it’s based on my belief that US West is not going to be left at the altar. If the deal goes through in the next three or four months, as I continue to predict, you will make the arb spread, a return of approximately 40 percent.”

When I said “short” Qwest shares, I was referring to the practice, used especially by arbitrageurs and hedge funds, of borrowing someone else’s stock and selling it with the commitment to buy it back later. The shortseller’s bet is that the stock’s price will fall and he can then buy back the shares at a lower price, pocketing the difference. I thought that either the merger of US West and Qwest would go through as planned or Deutsche Telekom would buy both US West and Qwest. In either case, US West would be bought out and the huge spread between US West’s deflated current price and the price Qwest was committed to paying would disappear, creating a huge profit for these investors.

It was not an easy situation to predict, especially given Nacchio’s tendency to shoot his mouth off, which is why I used the word “if.” But it seemed obvious that the market was acting irrationally and panicking. It was one of those rare moments of opportunity you hope for as an analyst.

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

The gossip and innuendo related to Deutsche Telekom, Qwest, and US West continued to build over the next few days, providing the perfect dramatic backdrop to my conference, which we renamed the CSFB Global Telecom CEO Conference. It was to be held in New York City at the Plaza between March 7 and 10, 2000. Without realizing it at the time, I presided over what was probably the last hurrah for the fearless leaders of telecom. My conference coincided perfectly with the absolute zenith of the bull market. There was a giddy hysteria to it that at the time was thrilling and contagious; looking back, it seems pathetic. Everyone there was making money hand over fist, from the executives whose stock options were soaring to the bankers who were awash in deal fees to the institutional investors who, armed with that extra edge, were getting to IPOs and M&A announcements just a little bit sooner than the rest of the world.

Our budget for the conference was an astounding $1.7 million, not as much as my investment banking colleague Frank Quattrone’s, but still a huge 70 percent more than what Merrill had allocated. And although I was still embarrassed by ostentation, I made sure the conference had all the trappings that executives and investors expected. I worked with a conference planner to choose entertainment, considering a lot of big-name performers, but ultimately chose the less showy comedian Darrell Hammond, the Saturday Night Live comedian most famous for his Bill Clinton impersonations.

Unfortunately, Hammond bombed. He made a lot of jokes about undeserving rich people that didn’t go over too well in this crowd. We also set up something called a “Telecom Café,” which had tons of Bloomberg machines for instant quotes and research, and flat-screen TVs so people could watch financial news shows. CNBC set up its own studio on the premises where its correspondents could interview our speakers. In the obligatory goody bag given to attendees, we provided everyone with a free MP3 player called the Rio. At the time, long before the iPod, this was one very cool gift.

From the moment the conference began that Tuesday, the town cars were lined up three deep outside the hotel, with over 1,500 institutional and corporate attendees jostling for a position in the Plaza’s Grand Ballroom to hear some of the 81 CEOs we had on the agenda. The venue was so crowded that it was physically difficult to get from one presentation to another, since the narrow hallways were clogged with frantic networking, card exchanges, and salesmanship. The CEOs were schmoozing the big money managers and either shopping for acquisition targets or trying to sell their own companies. CSFB bankers were trying to grease the wheels and earn some fees. And the investors were trying to find the next WorldCom, or at least hear what the old one had to say. Indeed, it was WorldCom’s Bernie Ebbers who would kick off the conference with a dinner speech. He had also agreed to do a small private meeting that afternoon at 4:30 PM with some of the largest institutional investors.

At about 3:00 PM, I took a final walk through the ballroom and the smaller meeting rooms to make sure everything was in order. The rooms looked great, and I wanted to relax for a few minutes before showtime, so I headed down the hall toward the elevator to go to my room and just happened to catch a glimpse of Bernie down at the end of a very long corridor. He was sitting at a table, but it looked as if he was just staring into space. He was completely alone—no handlers, no investor relations guys, no buy-siders, no bodyguards (he was worth nearly a billion dollars at this point). It was bizarre. I couldn’t remember ever seeing a CEO of a major corporation sitting by himself in a public place without someone to prep him or feed him or protect him or do whatever else might be necessary.

I said hi, then thanked him for coming to the conference and asked if there was anything he needed, such as a private room with a phone. We had arranged for a block of rooms for just these kinds of situations. “No,” he said, seeming deflated or even a bit depressed. “I’m fine right here, Dan.” Perhaps he was tired of doing all of these show-and-tells. Perhaps he had more weighty matters on his mind. I’ll never know what he was thinking, since he snapped to it and did a fabulous job at the meeting, but I remember it as a bizarre—and somewhat sad—moment.

Bernie’s dinner keynote address was a huge hit. Too many investors showed up, so we had to wheel TV sets out into the hallway to accommodate the overflow crowd. In his speech, he didn’t let slip any unusual estimates or display any slides showing changes in the revenue projections. No, he simply made fun of my height, as usual, and then went on to his favorite topic—the value of WorldCom shares.

“They put these podiums low enough for Dan to see over,” cracked Bernie, who stood six feet three. “I can’t see my papers.”3

I don’t think Bernie ever spoke into a microphone in my presence without playing the height card. He loved mocking people, and with me it was always the short-guy thing.

Bernie went on to ask the audience if it wanted to play “Do You Want to Be a Millionaire?” in a nod to the then-hot game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. “If you do,” he said, “go out and buy 42,000 shares of WorldCom stock and, by the end of this year, you will be a millionaire.”

The stock was then trading at $45 a share, so, although I didn’t figure it out immediately, it turned out he’d made a mistake. In trying to explain how owning WorldCom stock would make you rich, he’d said you should buy nearly $2 million worth of WorldCom stock in order to end up with $1 million. Ironically, by the end of that year, WorldCom’s stock would fall by about 50 percent, proving Bernie right. Maybe he really wasn’t very good with numbers, as his defense attorneys would later claim at his trial. Or maybe he knew what difficulties lay ahead and was giving everyone at my conference a between-the-lines heads-up. We’ll never know.

Bernie went on to discuss how business was booming for his company. “Over the past year, we have had a very, very specific focus,” he said. “We’ve added $4.7 billion in incremental revenue…we’ve increased net income by $2.6 billion, and we have invested about $8 billion…to further improve our network…. We’ve also integrated in the last year MCI, and have exceeded the synergy targets in every quarter….We’ve agreed to merge with Sprint and Sprint PCS and we’ve invested in wireless data…. With[WorldCom shares] trading at or below market multiples, why wouldn’t you invest and become a millionaire?”4

The audience ate it up. But anyone who chose that day to become a contestant on Bernie’s game show would certainly end up wishing that just like on the real Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, they could call a friend for advice or use one of their lifelines to escape.

The next morning, as I walked up to the podium in the ballroom to introduce the day’s first speaker, I felt a bit high. So much was happening in this one spot at this one moment in time. It really did feel like the epicenter of the telecom universe and the dawning of a new century, and I was, for a few days anyhow, Dick Clark. Actually, the analogy to New Year’s Rockin’ Eve was a lot closer than I realized, because it really was two minutes to midnight.

Midnight, for Wall Street, actually did come on March 10, 2000, the last day of my conference. That day, the NASDAQ hit its all-time high of 5,049 and thereafter began its death swoon. But for those few days, we all, even skeptical me, still believed that there was more good stuff to come.

In part, that was because virtually every one of our scores of speakers said so. Among the most prominent of our scheduled speakers, in addition to Bernie, were Steve Case, CEO of America Online; Vinod Khosla, the red-hot Internet venture capitalist; AT&T’s Michael Armstrong; and Qwest’s Joe Nacchio. Enron’s Jeff Skilling had signed on to come, but canceled at the last minute, citing a scheduling conflict. Almost all of them talked about the wave of insatiable demand for bandwidth, for high-speed Internet access over DSL lines, for anything that would make communications traffic grow faster.

Even the regulators were spouting the hype. Bill Kennard, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, sounded as if he were running a startup as he quoted that old standby statistic from 1997: “We know from the wireline world,” he said, “that Internet traffic doubles about every 100 days, and that’s a wonderful thing.”5

Kathleen Earley, head of AT&T’s Internet division, filled in for Armstrong at the last minute. She talked about “the end of business as usual.” “AT&T,” she said, “is the only company with all the pieces in place to be able to win in this space…we’re focused on exponentially increasing the number of eyeballs, eardrums, and end points to our network.”6 Even the superlatives had superlatives.

The other thing that really amped this conference was the ever-flapping gums of Joe Nacchio. The speculation continued to swirl over whether Deutsche Telekom would bid for Qwest and whether the offer would include US West. Both Joe and Sol Trujillo, US West’s CEO, were on the agenda to speak.

Qwest had confirmed on the evening of Sunday, March 5, just a few days after the rumor had interrupted my skiing, that it was in talks with a “major telecommunications company,” which everyone believed to be Deutsche Telekom. Deutsche Telekom and its chairman, Ron Sommer, had said nothing on the record. Just a few days earlier, Sol had announced that he would retire upon closure of the Qwest merger, which was supposed to happen within the next few months. “Joe and I have different styles, different approaches,” he said in an interview with The Denver Post. “There’s [sic] some things we don’t agree on. My belief is a CEO should have his stamp on it, and a company can’t have two different stamps on it.”7

All of this made for a delicious drama that would have worked on The Guiding Light if only Joe and Sol had been better looking. You could almost hear the syrupy voiceover and the melodramatic music: were the two going to kiss and make up, or would the Plaza be the site of a brawl between two rich guys in suits, with other rich guys in suits betting on the action? I certainly hoped that they’d play nice, since that would push US West shares up and narrow the arb spread. This would make my mountaintop call look very good indeed.

On the other hand, all of this tension certainly heightened the intensity of the conference and pleased CSFB’s senior management immensely. They loved the tidbits of news that allowed the salespeople to go out with what are called “proprietary calls” to the buy-side clients. And they really loved having the opportunity to introduce CSFB’s top dogs—CEO Allen Wheat; head of banking, Chuck Ward; and others—to the telecom CEOs, otherwise known as potential banking clients, speaking at my conference. Next to technology, telecom was bringing in the largest banking fees to Wall Street firms, and with the Sol and Joe theatrics, our conference was the hottest show in town.

Qwest’s Joe Nacchio arrived at the conference on Thursday, although he wasn’t scheduled to speak until Friday morning. He came early just to hang out, or maybe to talk still more. During the late-afternoon cocktail hour, Joe gathered up a large group of investors as well as a bunch of journalists who had been following him around like puppies, hoping he’d give them some more information about Deutsche Telekom. He discussed—loudly—how he loved US West but felt its top managers were too resistant to change. He claimed he was not in a major fight with them, but that they needed to understand that the telecom world of the future required faster decision-making and they needed to replace old, bureaucratic habits with newer, more entrepreneurial ones. Everyone nodded vigorously. This was, after all, the mantra of the new economy.

Just then, someone noticed what Joe was drinking. “So you’re drinking German beer,” the investor said. “Does that mean a Deutsche Telekom deal is imminent? Would you like to sell to them? What’s your minimum price and is US West in or out of the deal?” It was a mouthful, but investors tend to blurt out all their questions at once, figuring they’ll never sneak in another one with so many other people angling to get a word in.

Joe just looked at his beer, smirked, and said, “Oh, sure, I have a new-found fondness for German beer. It’s really quite good, you know. It’s a lot better than that Rocky Mountain beer.” In one casual comment, he had managed to dis his original merger partner, Denver-based US West, while kissing up to his new suitor, Deutsche Telekom. He was fueling the fire, and he knew it.

Whatever the truth, it made for great theater. Virtually every fund manager, buy-side analyst, arb, and hedge fund manager with any possible interest in telecom had hightailed it to the Plaza as soon as they realized that Joe and Sol were at the conference and squabbling with each other through the crowds of people gathered around the coffee stations. They were all hoping to pick up some shred of information that they could use to make a quick buck.

I didn’t really understand what game Joe was trying to play. It had been very reckless and even counterproductive to leak the potential Deutsche Telekom deal, in my view, because nothing had been signed and it could easily be called off. His implication that US West either would be left behind or would need to accept a lower price shocked US West shareholders, leading them to put enormous pressure on Sol Trujillo not to accept any change in the deal terms.

In my view, it would have made a lot more sense for Joe to quietly approach Sol and his board and discuss Deutsche Telekom’s offer, explaining that if US West gave up a little on the amount Qwest had offered to pay for it, Deutsche Telekom could pay a big enough price to make shareholders of both companies better off. This seemed like an obvious approach, but Joe apparently couldn’t keep his ego—or his mouth—under control. The share prices of Qwest and US West reflected the commotion, gyrating up and down with every interview and whispered—or shouted—conversation. Whichever paging transmitter was closest to the Plaza must have been in overdrive as buy-siders sent buy or sell orders back to their firms’ trading desks and their traders sent back the latest gossip they’d heard.

None of this banter showed up on the webcast of the conference that was available to day traders, the general public, and even retail brokers. This was the “professionals only” part of the insider game, but even the pros had no idea what was really going on: they were being manipulated by Joe, who himself may not have had a handle on what was about to happen.

Indeed, by the time he spoke to the crowds the next morning, his flirtation with a foreign suitor had come to an embarrassing end. The night before, March 9, Deutsche Telekom got cold feet. It rescinded its offer—if there ever had been one—and ended the talks. “Last night,” Joe announced, somehow seeming totally unfazed, “Qwest announced that it was informed by a major telecom company with whom it has been engaged in discussions that it has withdrawn from discussions to acquire Qwest and US West based on positions taken by US West.”8 That day, Qwest’s shares fell 12 percent on the news. US West fell as well, dropping 8 percent.

Ironically, that same day, the FCC gave its blessing to the Qwest–US West merger, and both sides tried their best to put a happy face on the sad debacle. “I know I’m in the middle of a merger. I know the reasons for doing the merger are true,” Joe Nacchio said in a poor attempt at trying to move forward. “You gotta operate with what you have.”9 “In a conference call with reporters later that day, Joe claimed that while he and Sol Trujillo had “different views,” the relationship remained “professional and cordial.”

From what I’d seen, “professional” and “cordial” had only that day become part of Joe’s vocabulary. Deutsche Telekom went on to buy Voice-Stream, now T-Mobile, the next year, and Qwest and US West consummated their marriage four months after the conference, just as the stock market began its radical shift downward.

My mountaintop call turned out to be the right one: the arb spread quickly narrowed, making anyone who took my advice a very healthy 38 percent profit in just four months. Those people would have bought US West shares at $72 per share on March 2 and sold them at $87 per share on June 30, the last day before the merger was completed and US West shares stopped trading. They also would have sold Qwest shares at $60 that same day and bought them back at $50 on June 30—making money on both sides of the trade. It was probably the best short-term call of my career. It was also my last good one.

“WorldCom is the poster child for buying real things with fake money.” That was a quote from a telecom consultant, Mark Bruneau of Renaissance Strategy Worldwide, in a Fortune article that ran April 17, 2000, called “Bernie’s Big Gamble.”10 True as this had been so far, WorldCom’s amazing streak of acquisitions was about to come to a screeching halt—thanks not to any problems with investors, who wanted the company to buy the world if it could, but to the people companies don’t think about when they’re small and nimble—the regulators.

By June, we were hearing rumors that the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division was carefully looking at WorldCom’s offer for Sprint and raising a lot of serious questions. I guess it made sense: the merger would concentrate much of the world’s long-distance and Internet traffic, and unlike the participants in many of the earlier deals, these were very similar companies with similar coverage, so overall competition could be reduced. With the antitrust issues looming, I decided that it was time to think about downgrading WorldCom shares from my Strong Buy, or “1,” rating. At this point, the vast majority of analysts had the same rating on the stock.

Ehud, Ido, and I sat down and tried to figure out the implications of WorldCom either abandoning Sprint and instead acquiring a wireless company, or buying Sprint but getting rid of a lot of its long distance business to satisfy antitrust concerns. An analyst named Scott Cleland, who ran an investment advisory service focused on federal government decisions, had recently predicted that the deal would not get U.S. antitrust approval. My Washington contacts saw this as entirely plausible as well, so I decided to work up some models reflecting several scenarios. They all came up with target prices for the stock that were lower than our current targets but still higher than WorldCom’s current price. Yet the risks meant that a Strong Buy, or “1,” rating was no longer justified.

So early in the morning of June 27, with WorldCom shares at $37.50, I lowered my WorldCom rating to Buy, the second-highest rating in CSFB’s four-point system, pointing out that if regulators rejected the Sprint deal, WorldCom would still need to acquire a wireless business and it was becoming more difficult to grow via acquisition. Our report was titled “WorldCom: There Must Be Some Way Out of Here—But All Lead to Lower Target Prices.” Its conclusion: “We believe the WorldCom/Sprint merger cannot proceed as originally proposed…. We are lowering our rating on WorldCom shares to buy from strong buy because all realistic scenarios yield significantly lower target prices….”11

I’m sorry I ever ran those alternative scenarios. I was far too mired in my detailed models to truly grasp the looming disaster. They beautifully quantified different share prices in different situations but did not show how WorldCom had been using a series of ever-larger acquisitions to hide a slowing core business. The company was already beginning to spiral out of control. Though I wasn’t mesmerized by the hype that had attracted many others to this stock, if I had been less analytic and more intuitive, as I had been in Tuscany and Vail, I might have better understood WorldCom’s addiction to acquisitions and, perhaps, aggressive accounting methods to fuel its continued growth. My lower rating was still too bullish. It did not capture what lay ahead for WorldCom and its investors.

Just as our 22-page report, finished at 2:30 that morning, was hitting the wires, Attorney General Janet Reno and Antitrust Division head Joel Klein announced that the government was filing suit to halt the merger. “This merger threatens to undermine the competitive gains achieved since the [Justice] Department challenged AT&T’s monopoly of the telecommunications industry 25 years ago,” Reno said. The merged company would control 30 percent of the market for long distance services between the United States and other countries and a combined 51 percent of Internet traffic, the government said.12 Faced with that pressure, WorldCom and Sprint announced later that day that they would withdraw the merger application and reconsider it after divesting certain assets. For all intents and purposes, the deal was doomed.

For me, the news came a day too early. If it had happened a day after my warning and downgrade, my clients could have saved serious money. But having it come out simultaneously meant that my call was useless to investors, as WorldCom and Sprint shares moved instantly on the news of the merger’s cancellation. Sprint shares dropped 2 percent while shares of WorldCom gained almost 6 percent, rising $2.06 to $39.69. The following day, WorldCom topped $42 per share, while Sprint fell another $5.63 to $52. Indeed, hope sprang eternal when it came to WorldCom’s stock. Within three weeks, WorldCom shares had risen even further, hitting $47 per share and making my downgrade look pretty bad.

IN PREPARATION for WorldCom’s second-quarter earnings results, we did everything that we could do in advance to get a written report out quickly. That meant setting up a pre-written template of a short report, which we called Quick Notes, that we would rush out as soon as we got the numbers and assessed whether we needed to change our forecast or rating. Our goal was to get a Quick Note out within an hour or two of a company’s press release, but it was always tricky. Even after we’d done our bit, we had to get compliance to approve it, which took at least 30 minutes and sometimes over an hour.

At 8:16 on Thursday morning, July 27, 2000, WorldCom’s second-quarter earnings hit the wires. Ehud, Ido, and I scurried to scan the press release for any telling words, then crunch the numbers, and get the Quick Note together before Bernie and Scott held an investor conference call at 10:00 AM. We quickly realized that WorldCom’s earnings were a penny shy of our forecast, and that revenues had grown only 13.3 percent, below our 14.0 percent forecast, with the shortfall coming almost entirely from Internet revenues.

One of the reasons investors had such unyielding faith in Bernie and Scott was that they delivered time after time. Before this stretch of disappointments, WorldCom had had an incredible record of meeting or beating expectations. Yet this was the second quarter in a row that they hadn’t hit the numbers. I was concerned, but these dribs and drabs of bad news still seemed to be just that. Still, I had to react: the markets would be opening at 9:30 AM, which meant clients and salespeople would need time before then to get their orders ready. So I summarized the shortfall, lowered my revenue growth forecast for 2000 to 13.5 percent from 14.0 percent, and recalculated the target price, figuring I’d done the best I could in the time allotted. The changes were not enough to justify a further rating reduction, in my view.

But I looked pretty pathetic when at 8:49, just 33 minutes after WorldCom’s press release came out, Jack’s clients began to receive his 10-page report full of lengthy analyses, tables, and charts. It was amazing in its detail, which was far more voluminous and precise than anything in the company’s press release, and even more detailed than anything that would be mentioned in the conference call, which wouldn’t take place for another hour. Some clients forwarded the e-mail to me almost immediately. Scott’s earlier assurance to me that “that stuff is not going on anymore” with Jack sure looked like a lie.

“I can’t believe what is going on here,” I raged to my team. “In order to understand the WorldCom quarter in its full details and to know what my clients already know, I have to read a competitor’s report! Am I that bad an analyst,” I asked sarcastically, “or is there something shady going on here?”

To be fair, it was not illegal for Jack to publish whatever information he had, provided he did not receive it while over the Wall and working with Salomon Smith Barney’s bankers. Assuming he made the information available to everyone simultaneously and thus didn’t favor one client over others, he would have been following the rules of the Institute for Chartered Financial Analysts, an organization that certifies securities analysts. The wrongdoing, if it existed, was on the part of WorldCom if someone there indeed passed the results to Jack before announcing them to the public, which is what I believed was happening. There was no way he could have absorbed, analyzed, written, and gotten compliance approval in those 33 minutes.

I’ve never understood what WorldCom gained by giving Jack advance notice and information. First, there was the legal risk; second, this treatment bolstered his credibility to the point that people believed him more than WorldCom’s own executives, as we saw with the revenue-growth story at his conference earlier in 2000. It worked to the detriment of Jack’s competitors, including me, but wouldn’t a company want as many voices on the Street as possible? What if Jack changed his tune on the company? Or did they have a reason to believe that Jack simply wouldn’t ever change his tune, and thus this was the best possible way to ensure that there would always be at least one loyal cheerleader, even if the home team was getting routed?

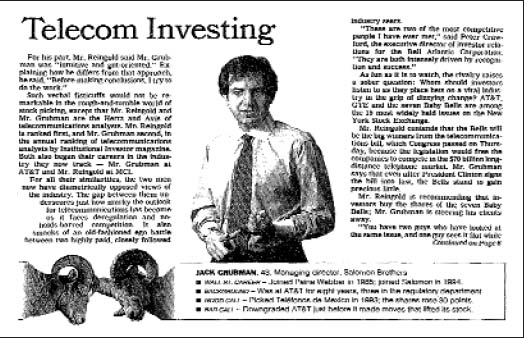

What I kept butting my head against was the reality that Jack’s style of doing business was now the style of doing business, wrong, right, or what have you. Back in May, Business Week had published a huge feature on Jack titled “The Power Broker,” written by Peter Elstrom. With an opening spread featuring Jack, hands on hips, looking off to the side as if he were gazing into a crystal ball, it somehow managed to burnish his image at the same time that it exposed a lot of the lines he was crossing, many of which he readily volunteered. “You don’t know Jack?” it read. “You should. In the past four years, as the deregulated telecom marketplace has exploded with possibilities, so too has the influence of Jack Benjamin Grubman.”13

The article discussed his influence on the banking side, asserting he’d played a major role in bringing in $5.7 billion in telecom IPOs to Salomon Smith Barney since 1997, and wondered aloud about the conflicts of interest he seemed to invite. It also mentioned that he’d embellished his résumé, saying he’d graduated from MIT when it had been Boston University and that he’d grown up in tough South Philadelphia, home of Rocky Balboa, when in reality it had been a not-so colorful middle-class neighborhood in Northeast Philly. “At some point, I probably felt insecure,” he said by way of excuse.

The story continued: “‘What used to be a conflict is now a synergy,’ he says. ‘Someone like me who is banking-intensive would have been looked at disdainfully by the buy side 15 years ago. Now they know that I’m in the flow of what’s going on. That helps me help them think about the industry.’”

When asked about such close ties affecting objectivity, he scoffed. “‘Objective? The other word for it is uninformed,’ he said.”14 I read the piece and said to myself—and to anyone who would listen—this guy was a reckless fool and might end up in jail, pulling others down with him.

Our “uninformed” team spent a very long day and grueling night preparing an in-depth review of WorldCom’s results. The report was published the next morning at 7:30 AM, almost 23 hours after Jack’s tome had hit the buy-side’s e-mail boxes. And we still didn’t have all the information he had. The only thing I knew for sure was that if anything else started to go sour at WorldCom, I wasn’t going to be the first to know.

I couldn’t have been more right. About a month and a half later, on September 6, Ehud and I were in a taxi, on our way from the Kansas City Airport to Sprint’s headquarters for a day of meetings. My pager went off with a message from Ido that WorldCom was buying Intermedia, a startup local carrier and Web-hosting company, and that a conference call had just started. Fortunately, we had a long drive from the airport, so we each called in on our cell phones. We’d missed Bernie’s introduction, but Scott Sullivan had just come on to describe how the purchase would impact earnings. He said it would reduce 2001 earnings per share by 10 to 12 cents, which translated, he said, “into $2.13 to $2.15 a share.” Everything at WorldCom, Scott said, remained on track.

Ehud and I looked at each other, mystified. “On track?” I mouthed silently. Our estimate had been $2.42 a share, which we knew was just a tad above the $2.40 the company had been comfortable with on July 27, when it had reported its second-quarter results. So with this deal, Scott’s numbers should be down to around $2.28 to $2.30, not the much lower range Scott had just predicted.

My first reaction was to be furious with Ehud, because I jumped to the conclusion that WorldCom had guided earnings downward, perhaps while I was on vacation in August, and that somehow he had missed it. I put my hand over the phone and snapped “What’s going on? Are our estimates way out of the range or what?” Yet I also suspected that Scott had a way of always assuring everyone that everything was fine, even as it was being altered for the worse.

Ehud, though relatively new to the business, was razor sharp and rarely made a mistake. “I’m almost positive they haven’t altered their guidance since the call at the end of July, and it was $2.40 then. That I know for sure.” I asked what the First Call consensus estimate was—an average of all the analyst estimates—but he didn’t know offhand and suggested having Ido or Julia check it back at the office.

“We don’t have time,” I said. “If he did something sleazy, I’ve got to expose it on this call when we get to Q&A.” So, risking the embarrassment of having missed something that everyone else knew, I asked the following question on the call with some 1,000 investors listening in:

“Scott, could you please repeat your EPS guidance for 2001? I’m not sure I heard it right. Did you say the new range is $2.13 to $2.15, down 10 to 12 cents?”

“Well, Dan, not exactly,” Scott said. “I said down 10 to 12 cents from the expectations of the major people who follow the stock.”

“That’s weird,” I said. “My estimate is $2.42, so I’ve lost 15 cents or more somehow.”

“Dan, I don’t know why your number is so high,” Scott said, essentially confirming his lower numbers. “Others are at $2.25.”

As we pulled up to Sprint’s headquarters, I shot another look at Ehud. Did he mess up royally, or were we exposing the CFO of one of the largest and best-loved companies in the world as a liar? We had to go to our meetings, so we’d have to wait until later to find out who was right. In the meantime WorldCom’s shares were dropping like a lead balloon. Perhaps people were going back and looking at their models and realizing that Scott had just sneaked in a 15 cent, or 6.3 percent, cut in his earnings estimates for the year, a shocking half-billion dollar reduction in WorldCom’s earnings outlook. WorldCom shares fell 17 percent from $36.93 to $30.56 and Intermedia shares soared 34 percent from $22.87 to $30.69 over the next three days.

When we were able to call Ido and get the First Call numbers, we found that Ehud was right, as usual. The average or consensus earnings forecast remained at $2.40—although it turned out that three analysts—Jack, Frank Governali of Goldman, and Eric Strumingher of PaineWebber—had lowered their estimates to $2.25 in the previous month. Jack had been first, of course, on August 4, while Strumingher had come down just a week ago, on the 28th. The other 16 of us were either on vacation during much of August and out of touch with the company or were not privy to the real story. Scott may have guided Jack down first, and the other two, being smart and attentive, may have seen his change and contacted the company to try to figure out what had made him do it.

Clearly, if there was bad news, WorldCom preferred it to come out of the mouth of its biggest supporter. It’s also possible that he did some good analytic work on his own, finding some issues that jeopardized WorldCom’s ability to meet its $2.40 estimate and writing it up for all to see. In that case, the rest of us had simply been asleep at the switch. Still, at this point, I saw an inside job in just about everything that happened with WorldCom or Jack. Amazingly, we tried to listen to the tape of this call about a day later, and found, to our surprise, that my questions and Scott’s answers to them had been mysteriously deleted. The rest of the Q&A session remained unaltered. But at least 1,000 people had heard our exchange and Ido had made his own recording anyway. What a Rosemary Woods moment.

None of this was necessarily illegal—just underhanded, unethical, and unfair—but it was about to become so. Just the month before, in August of 2000, the SEC, under Chairman Arthur Levitt, had approved a new rule aimed at ending exactly this process of “selective disclosure.” This meant, according to the SEC, situations “whereby officials of public companies provide information to Wall Street insiders prior to making the information available to the general public.”15 Levitt had correctly argued that such leaks, or “whispers” as they were known, disadvantaged not only the general public but also those professionals who were not the first to get important information from a company.

Once Regulation FD (Fair Disclosure) went into effect in October of 2000, all of these whispers from a company to an analyst became illegal. A lot of analysts—and their bosses at their firms—worried that the new rules would make it very hard for them to do their jobs. These new rules would make clear just how much of their vaunted expertise came from having access to executives and information that others didn’t. As experts able to interpret news and information, research analysts still had value. But for anyone who relied on tips rather than analysis, Reg FD meant big trouble.

I supported FD as one of the few things Arthur Levitt had done since coming into the job in 1993 that might help investors. I figured that it would make analysts do their own homework instead of relying on management guidance. I also thought it would have an unintended effect of creating more stock-price volatility because companies would hold back information until there was enough to merit issuing a press release, which would then create a shock. This was because Reg FD made it no longer acceptable to do a slow leak à la MCI in the old days.

By the Fall of 2000, it was obvious that what many people had believed was just another protracted episode of volatility was, in fact, a true market crash—at least on the NASDAQ, which had dropped 39 percent since its March 10 peak. Dot-coms such as Pets.com and Boo.com were in dire straits or had already gone under; layoffs had replaced luaus; and tech funding was rapidly drying up. But even though tech and telecom had in many ways become fully entwined, now the two paths seemed to be diverging, in my view.

I had been cynical about many of these tech startups from the beginning, so I didn’t find the news of their demise particularly surprising. So many of the newly public dot-com companies were just ideas, with hardly any customers or assets and virtually no barriers to entry by other competitors. The telecom companies that I covered, on the other hand, were for the most part proven businesses with real customers, revenues, cash coming in, and assets. And those that weren’t, like Qwest and Global Crossing, had purchased real companies in US West and Frontier, which hedged their new-economy bet. So while the phone companies weren’t looking nearly as good as they had early in 2000, they were still looking pretty good.

But the long distance sector of the market was suddenly in real trouble, starting with AT&T. Mike Armstrong’s attempt to plow over the soil and grow an energetic new culture at AT&T was failing. Having cobbled together a telecommunications company that seemed to have all the parts—long distance and local, voice and data, wireless and wired, video and high-speed access—in the hope of getting a head start on the Baby Bells, Armstrong found that integrating them was a lot harder than buying them. Huge turf wars inside AT&T continued to rage among people fighting to defend their various fiefdoms, and the company was filled with antiquated computer systems that didn’t talk to each other and people running them who didn’t either.

For example, even though AT&T had purchased McCaw in 1993 and made it the core of its cellular offering, AT&T Wireless and AT&T long distance customers were still, seven years later, not receiving one unified invoice because the two units were still using different billing systems. Armstrong had been trying hard to bring some entrepreneurial verve to this company, but it turned out that AT&T didn’t have the ability to absorb it in its DNA.

At the same time, competition had intensified in the traditional long distance business, the business that provided virtually all of the company’s earnings and cash flow. There were just too many rivals now, ranging from the Bells to WorldCom to Qwest and numerous wireless companies offering free long distance. Ironically, it was AT&T that, in 1998, had first introduced free long distance for its wireless customers, called the One Rate Plan. This had quickly turned long distance into a commodity, with perhaps the most corrosive effect on AT&T itself.

By October of 2000, AT&T’s shares were mired in a decline that had begun shortly after the announcement of the AT&T Wireless IPO back in 1999. On October 4, 2000, The Wall Street Journal ran a story on the front page of its Money & Investing section about Jack’s ill-timed upgrade of AT&T, hinting that it might hurt Salomon Smith Barney’s banking business, which had hit a phenomenal $350 million in fees in 1999. It read, “everyone seemed to win—everyone, that is, except investors who heeded his call and bought AT&T stock.”16

Incredibly, two days after the article appeared, Jack reversed himself again, downgrading AT&T shares to a “2,” or Outperform. The downgrade shocked most of the media and Salomon Smith Barney’s brokerage clients, but it was old news for many of the professionals. Back in May, when Jack rated AT&T shares a Buy, or “1,” and just after the AT&T Wireless IPO was completed with a $63 million payoff to Jack’s firm, I received an e-mail from a client who worked for a hedge fund. “Fyi, Jack is pissing all over AT&T,” he wrote, suggesting that Jack’s private comments to some institutional investors were far more bearish than his written reports, which Salomon Smith Barney’s brokers and individual investors relied upon.

Jack’s tactics were finally attracting some negative attention. I was happy about it, and I wasn’t the only one. Just after the Journal article came out, I got an e-mail from Frank Quattrone. Ever the competitor, he saw the negative articles about Jack as a major opportunity.

“Hey,” he wrote, “Grubby-man is getting drubbed on the att round trip. Major oppty for you to crush him for good. Planning any major marketing/advertising events?”

Unlike Frank, I wasn’t much of a self-promoter, so I simply responded, “Any ideas?” and the discussion ended there. I was glad I wasn’t the only one noticing Jack’s diminished status.

It was at about this time that AT&T’s Armstrong decided to throw in the towel on his cosmic strategy of integrating voice, video, and wireless into one bundle of services. Instead, he decided to break up AT&T all over again by dividing the company into three completely separate companies—AT&T Long Distance, AT&T Wireless, and AT&T Broadband (cable TV and modern services). Unbeknownst to me, CSFB and Goldman bankers had been brought in to plan the restructuring. On October 23, I was called over the Wall, along with Goldman’s telecom analyst, Frank Governali, to hear a preview of what Mike and his CFO, Chuck Noski, would say the next day at a hastily arranged analyst meeting.

We met secretly in AT&T’s virtually uninhabited downtown Manhattan offices at the foot of Sixth Avenue. Almost all of AT&T’s executives worked out of the New Jersey headquarters, but the company had kept the building to use for New York meetings. They had draft slides ready to go and wasted no time getting down to business. I had had no advance briefing from Chris Lawrence, CSFB’S AT&T banker, or his team, so this was all brand-new to me.

I was amazed that Mike was giving up on integration. I asked why a few different ways, but he only said that the stock had been pounded and that the market wasn’t giving credit to the company’s long-run strategy. In effect, he was saying that the market’s myopia was forcing him to abandon his grand transformation plan. He seemed exhausted more than frustrated. Yet by the next morning he would be back to his ebullient self, confident smile and John Wayne voice at the ready.

And then AT&T’s CFO, Chuck Noski, told Goldman’s Frank Governali and me what Mike Armstrong was planning to announce about earnings and revenues. It was horrendous. The competitive pressures from WorldCom, Sprint, several new startups, and, of course the Bells, were causing AT&T to lose share and cut prices at a far faster pace than expected. I was suffering along with the company, having recommended AT&T at Merrill almost two years earlier, at a post-split $52 per share. AT&T shares had fallen 48 percent since then and were now trading at $27.

With the exception of IDB back in 1994, upgrading AT&T had been my worst stock call ever, and things had only gotten steadily worse. But now, with me over the Wall and CSFB likely to be advising AT&T for the next year or two, I didn’t think I should be issuing any opinions. CSFB’s compliance officers agreed, so I was instantly restricted from commenting on AT&T and its shares. From October 23, 2000, I couldn’t write or say a word about AT&T. As frustrating as this was, I was also relieved: my call had been a disaster and this, at least, stopped the bleeding.

The analyst meeting didn’t go over well. AT&T shares fell another 13 percent. And the market was beginning to realize that the disease that was afflicting AT&T—brutal competition for long distance services, the move to make long distance free for cellular calls, and the muscle of the Baby Bells—was beginning to give the other long distance companies more than a sniffle as well.

Except, that is, for good old Qwest. Exactly a week after AT&T’s dour earnings announcement, Qwest held an all-day analyst meeting in Manhattan, at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. As we sat in the Grand Ballroom awaiting Joe Nacchio’s talk, the mood was defiantly confident. It seemed the polar opposite of the morose tone of the AT&T meeting. Clearly, whatever one thought of Joe, he was doing something right. Qwest continued to thrive, reporting robust and on-target growth in revenues and operating cash flow.

Suddenly, the lights dimmed and the stage lit up. Out marched Joe, dressed in full Australian outback regalia and pith helmet, to the overdramatic sounds of the music from the hit TV show Survivor. Arrayed around the stage were a series of burning torches, each one representing one of Qwest’s competitors. There was a torch for AT&T, another for WorldCom, and one torch each for Sprint, Global Crossing, Verizon (the former Bell Atlantic), and several of the other Baby Bells. You can imagine what came next. Nacchio, completely in his element, traipsed merrily across the stage to each one of his rivals’ torches and delivered a short monologue on what was wrong with each one of them. Then, with evident pleasure, he snuffed out each of their flames.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with the other guys in the industry,” he repeated over and over during the course of the meeting, “but Qwest is doing just fine.” Yes, he acknowledged, the economy was soft in a few regions, but US West’s regional economy was resilient and other growth sources, such as data, Internet services, and wireless services, were more than compensating. Then there was the stability of US West’s local business, which was still more or less a monopoly. If there was to be only one Survivor, he assured all of us, it would be Qwest.

While the skit was silly, those of us still recommending Qwest’s shares found the meeting somewhat of a relief. There were still some winners in this sector, and what seemed to be happening was that the day of reckoning for the incumbent long-distance companies that I had warned about five years earlier was upon us. Some companies were getting their lunches eaten; others were prospering. It wasn’t a slowdown in overall demand as much as a Darwinian shakeout.

But that sense of relief didn’t last long. Just as I was leaving the Qwest meeting, I got word that WorldCom was holding a surprise analyst meeting in New York the next day, November 1. I figured it was going to be bad news, and it was. I intentionally arrived early at the meeting, about 6:45 AM, to get the press release as soon as it came out at 7:00 AM. It announced that WorldCom was going to create two, yep, tracking stocks, one for services to businesses and one for services to consumers.

More significant, it also was reducing its growth projections due to “intense pricing pressures, unfavorable foreign exchange rates and the shift of consumer voice to wireless technologies.”17 Though the new targets were dismal, it sure looked as if Scott Sullivan and his team had done extremely detailed analyses of WorldCom’s various lines of business.

Wow, I thought, these are huge cuts. The water torture of the past three quarters had turned into a downpour. I knew this would be very bad for WorldCom’s share price, and I knew I needed to tell CSFB’s sales force as quickly as possible. But first I wanted to get a better understanding of what was happening. Bernie was not around yet, but I found Scott and asked a few questions about what was driving the bad news. He had some pretty logical answers that were consistent with Armstrong’s answers a week earlier. When I asked about his new forecasts, he said he would not talk about them until Bernie made his opening remarks. Realizing that I wasn’t going to get much more from him and that CSFB’s morning meeting would be ending soon, I pulled out my BlackBerry and started to type up an e-mail to CSFB’s sales force.

With its wireless e-mail capability, the BlackBerry had completely transformed my job: no more racing to beat my competitors to the phone banks, no more having to wait until a meeting was over to get my thoughts back to my team or the sales force. I decided to immediately downgrade WorldCom’s shares for the second time this year, this time from Buy, or “2,” to Hold, or “3.” I also dramatically lowered my earnings estimates for 2001 to $1.10 per share, down 46 percent from my prior estimate of $2.02. A huge $2.7 billion dollars of annual profit had just disappeared.

At the meeting, even Bernie seemed humbled, a shadow of his former swaggering self. “We recognize we have let you down,” he said, promising to do better. “When I was 16 years old, I was a six-foot-three, 130-pound kid trying out for the high school basketball team. I was one of six Anglo-Saxon kids among a Native American community. Our coach didn’t speak English. I was competing for starting center against a kid the same height but 100 pounds heavier. The coach threw the ball out into the center of the court and said whoever comes up with the ball is the starter. I came up with it. We are going to come up with the ball too. We are going to right this effort as never before.”

Later, he was a lot less sanguine. “People have a legitimate right to ask if I’m the right person to lead the company,” he told reporters after the meeting.18

WorldCom’s announcement was an unmitigated disaster for virtually everyone in the investment world. Lots of professional fund managers still owned the stock, which had already been suffering and was about to get crushed, and virtually all Wall Street analysts were still recommending it. The only thing that made the pain bearable for us was the fact that this business was all about comparative performance. So if we all got hosed, at least we were all in it together.

A day later, two other investment banks downgraded WorldCom shares: Merrill Lynch, with my former colleague Adam Quinton, and Wachovia Securities, both from “Buy, or “1,” to Neutral, or “3.” Salomon Smith Barney and J.P. Morgan were handling the tracking-stock deal, so I assumed they would not comment.

But I had forgotten once again about the SEC’s No-Action Letter. Jack reiterated his Buy, or “1,” rating, in a lengthy report approved by his compliance department, as did the analyst at JP Morgan. By this point, compliance lawyers could drive an oil tanker through the loopholes in the SEC regulations, with plenty of room left over for an investment bank and its analyst to do whatever they wanted. Thanks to the No-Action Letter, analysts knew they could write about virtually anything they pleased, conflict or no conflict, with no fear of getting in trouble. Arthur Levitt’s sleepy SEC appeared to pay not a whit of attention.

What had at first seemed like a bit of softness for one company had mushroomed into a calamity for all of the long distance incumbents. On November 3, Sprint held an analyst meeting that was a virtual carbon copy of the others, except it didn’t announce a tracking stock, because it already had one. I was of two minds as I tried to digest the news. On one hand, I was devastated to have missed the biggest and most bearish nine-day period ever for the incumbent long-distance companies. Dammit, I thought, if only I had stuck with that position that I had launched with a bang back in July of 1995 and never upgraded those stocks to Buys. I should have ignored all the data and Internet hoopla and stuck to my narrow argument that the voice long distance business was going to get creamed.

On the other hand, I felt a kind of guilty vindication. My overall theory that the Baby Bells were the best situated to compete in this market had been strengthened, not weakened, by what had just transpired. Now WorldCom, Sprint, and AT&T were too weak and too distracted to attack the local market, giving the Baby Bells still more power.

In our insular Wall Street world, I suddenly looked a lot better than a lot of my competitors. Clients began calling to congratulate me, citing both my relatively early downgrade of WorldCom and the fact that my argument of five years ago was beginning to bear fruit. Jack, they said, was no longer looking as savvy as he had just a few months earlier. An important shift was happening, we all intuitively understood. What we didn’t yet understand was exactly how seismic it would become, and how devastating the results would be.