and

and  ; correctly identifying the Minoan words for “boy” and “girl,” noted together in 1927 and likewise indistinguishable; and being the first to pinpoint the special meaning of the sign

; correctly identifying the Minoan words for “boy” and “girl,” noted together in 1927 and likewise indistinguishable; and being the first to pinpoint the special meaning of the sign  , a discovery previously attributed to Ventris.

, a discovery previously attributed to Ventris.New York, 1946

ON THE EVENING OF JUNE 15, a small, sober-looking woman stood before an audience at Hunter College in Manhattan. The college was her alma mater, and now, two decades after her own luminous career there, she had been invited to address the new crop of Phi Beta Kappa initiates, Hunter’s brightest students.

She was by nature self-contained, and speaking in public made her unbearably nervous; each time she did it, she vowed it would be the last. Her talk, like everything else she wrote, was the product of hours of meticulous planning, composition, and revision—she typically put each of her published papers through a good ten drafts until she was satisfied. Before her now was her typescript, its handwritten emendations in her tidy pedagogical script attesting to continued reflection and reworking.

Physically, she was unprepossessing—perhaps, in the parlance of the day, even plain. Short and roundish, she had neat, unstylish hair and dress; solemn, heavy-lidded eyes framed by spectacles; and a thin mouth that gave the impression of primness. Though she was not yet forty, she seemed, like many academic women of her era, prematurely and irretrievably middle-aged.

But as soon as she began to speak, her words had the hypnotic pull of a fairy tale:

On every kind of writing material known to man, on paper, parchment, papyrus, palm-leaves, on wood, on clay, brick, or stone, on every kind of metal, there exist inscriptions which cannot be read. Sometimes they cannot be read because the system of writing is unknown, and sometimes because, although we know what sounds to ascribe to the different signs, the language is unknown.

These documents range in date all the way from Neolithic times to the present. Some are probably in the process of being written at this very moment. Those, however, that were written at periods which we may call the fringes of history, are especially important for the light that they may cast on the past. …

The woman was Alice Kober, an assistant professor of classics at Brooklyn College. By day, she taught a cumbersome load of classes, as many as five at a time—things like Introductory Latin, and Classics in Translation. By night, working almost entirely on her own, as she had for the past fifteen years, she chipped away, methodically and insistently, at the scripts of Minoan Crete. Now, at thirty-nine, although few people knew it, she was the world’s foremost expert on Linear B.

Though she is all but forgotten today, Alice Kober single-handedly brought the decipherment of Linear B closer to fruition than anyone before her. That she very nearly solved the riddle is a testament to the snap and rigor of her mind, the ferocity of her determination, and the unimpeachable rationality of her method. Kober was “the person on whom an astute bettor with full insider information would have placed a wager” to decipher the script, as Thomas Palaima, an authority on ancient Aegean writing, has observed.

Strikingly, she got as far as she did without being able to see any of the tablets firsthand. Even more remarkable was the fact that by the time she addressed the group at Hunter, Kober had already done groundbreaking work on Linear B in an era when there were barely two hundred inscriptions available for study.

That Kober’s vital contribution to the decipherment has been largely overlooked is due in great measure to her early death, in 1950, just two years before Michael Ventris cracked the code. It is also due to her quiet, deliberate way of working, step by incremental step, never committing her ideas to print until they met her exacting standards of proof. As a result, she published little—it was more than enough for her, she used to say, to come out with one good article a year. But though her major work spans barely half a decade, from 1945 to 1949, she is now regarded as having built the solid, unassailable foundation on which Ventris’s decipherment was erected. For as Ventris himself acknowledged publicly not long before his own untimely death, he had arrived at his solution using the methods Alice Kober had so painstakingly devised.

Along the way, Kober solved a host of small mysteries, many of which had bedeviled investigators from Arthur Evans onward. Among them were these: proving which sign depicted the male animal and which the female in paired logograms like  and

and  ; correctly identifying the Minoan words for “boy” and “girl,” noted together in 1927 and likewise indistinguishable; and being the first to pinpoint the special meaning of the sign

; correctly identifying the Minoan words for “boy” and “girl,” noted together in 1927 and likewise indistinguishable; and being the first to pinpoint the special meaning of the sign  , a discovery previously attributed to Ventris.

, a discovery previously attributed to Ventris.

But Kober also made much larger discoveries—findings that illuminated the internal workings of Linear B words and symbols—and it was these that had profound implications for Ventris’s solution. Her work reads like a how-to manual for archaeological decipherment, something acutely needed for Linear B, a textbook case of an unknown script writing an unknown language. “There is no certain clue to the language of the Minoan scripts,” Kober said in a 1948 lecture at Yale. “All we have are the inscriptions they left, and the symbols they contain.” She added: “To get further, it is necessary to develop a science of graphics.” It was just such a science that Kober, from the first, had set out to construct.

NO ONE BELIEVED Alice Kober when she declared she would make the Minoan scripts her lifework. The year was 1928, and she announced her ambition upon her own graduation from Hunter College. At first glance, she seemed an unlikely candidate to solve a mystery that had already endured for almost three decades. She was young—barely twenty-one—and though she had majored in classics, she had none of the specialized background in historical linguistics that might have put such a calling within reach. Nor was she trained in archaeology, statistics, or any other discipline essential to the decipherer’s art.

Above all, she simply did not look the part: With its aura of bravura, derring-do, and more than a dash of imperialism, archaeological decipherment was the time-honored province of moneyed European men. That the upstart American daughter of working-class immigrants would even contemplate the field was dismissed as youthful fantasy.

But in the coming years, on her own time, Kober would systematically acquire every needed weapon in the decipherer’s arsenal. She learned a spate of ancient languages and scripts with the methodical ardor of a Champollion. She studied archaeology, linguistics, statistics, and, for their methodology, physics, chemistry, astronomy, and mathematics. All this—more than a decade of concerted study—she did merely to lay the groundwork for her eventual assault on Linear B.

In 1942, Michael Ventris, then only twenty but already passionately interested in the Cretan scripts, wrote confidently from London, “One can remain sure that no Champollion is working quietly in a corner” on the riddle of Linear B. But in fact there was, directly across the Atlantic, sitting quietly at the dining room table of her modest Brooklyn house, ever-present cigarette at hand, and “working hundreds of hours with a slide-rule,” as she later wrote. For it was Alice Kober, like Champollion in his day, who imposed scientific precision on the romantic, undisciplined attempts that had gone before. To the riddle of Linear B she brought the skills of a crack forensic analyst in a detective story, who gleans vital information after lesser investigators have trampled through, an unflappable Holmes in a sea of Lestrades. It was only fitting that she, who savored detective stories in what small spare time she had, would give the decipherment the “method and order” she so esteemed.

* * *

ALICE ELIZABETH KOBER was born in Manhattan on December 23, 1906, the elder of two children of Franz and Katharina Kober. Her parents had come to the United States from Hungary earlier that year; Katharina would have been pregnant with Alice when they arrived in May. The couple settled in Yorkville, a historically German and Hungarian neighborhood on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Census records list Franz’s occupation as upholsterer and, in later years, apartment-building superintendent. A son, William, was born to the Kobers two years after Alice.

Few traces of Kober’s early life are extant. As a teenager, she attended Hunter College High School, one of the city’s elite public schools, which, like Hunter College itself, was then for women only. In the summer of 1924, she placed third among 115 New York City high school seniors in a statewide college scholarship contest. Her prize, a hundred dollars a year for four years (about $1,300 a year today), was undoubtedly welcome in a family of modest means. That fall, she entered Hunter College, where she took part in the Classical Club and the German Club.

Even in a college known for its brilliant young women, Kober by all accounts stood out. “As an undergraduate she impressed me by her earnest application to her work, and even more by her independent judgment, which let her accept no statement of the teacher without subjecting it to critical study,” one of her professors, the classicist Ernst Reiss, later wrote. “Coupled with this was a still more valuable trait, an intellectual honesty, which induced her readily to revise her own opinion when she became convinced of the correctness of the opposition.”

At Hunter, Kober took a course in early Greek life, and it seems to have been there that she encountered the Minoan scripts. In 1928, she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa; she graduated magna cum laude that year, with a major in Latin and a minor in Greek. (C’s and D’s in gym appear to have put summa cum laude out of reach.) Accepted to graduate school at Columbia, she earned a master’s degree in classics in 1929, followed by a Ph.D. in classics there in 1932.

Kober’s passage through graduate school, rapid by any standards, was all the more impressive in that she was working the entire time, first at Hunter High School, where she was a substitute Latin teacher, and afterward at Hunter College, where she was an instructor in Greek and Latin. In 1930, two years before she was awarded her doctorate, Alice Kober, then not quite twenty-four, became an instructor at the newly created Brooklyn College at an annual salary of $2,148—just under $30,000 today.

The archaeologist Eva Brann, who studied with Kober at Brooklyn in the late 1940s, recalled her teacher’s “dry, refraining rigor” in a biographical essay written in 2005:

She was, to coin a phrase, aggressively nondescript, or so it seems to me now. She wore drapy, dowdily feminine dresses; something mauve comes before my eyes. Her figure was dumpy with sloping shoulders, her chin heavily determined, her hair styled for minimum maintenance, her eyes behind bottle-bottom glasses snapped impatiently and twinkled not unkindly. Her classroom manner was soberly undramatic, drily down to earth, in no way a performance, but instead demandingly definite. I can’t tell whether I remember from observation or infer on reflection that her lectures were very good, forceful and full of matter, but I know that I loved listening.

Toward those she did not respect intellectually (and there were many), Kober could be withering. In a 1947 letter to a colleague, she loosed her scorn on the eminent Czech linguist Bedřich Hrozný. Hrozný had made his name by deciphering ancient Hittite in the 1910s and was just then attempting to do the same for Minoan, with conspicuously less success. “Everybody seems to handle Hrozný with kid gloves,” Kober wrote. “I suppose it’s because nobody thinks a man with Hrozný’s reputation could possibly be as stupid as he seems.”

Her harshest criticism, though, was reserved for herself. In 1947, she sent the editor of the journal Classical Weekly a lecture on the Cretan scripts he had solicited for publication. Her cover letter read, revealingly: “When you wrote me in May, 1946 I answered that I didn’t think it was worth printing. … It still seems to me that it isn’t quite the thing for the Classical Weekly, though it isn’t as bad as I thought it was at the time. … The subject is one, as you will see, to which I have a strong emotional reaction, and emotion and scholarship do not belong together.”

Her life was her work, and what a great deal of work there was. Kober never married, nor is there evidence she ever had a romantic partner. After her father’s death from stomach cancer in 1935, and with her brother grown and gone, she and her mother lived together in the house Alice owned in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. It was there, night after night, after her classes were taught and her papers graded, that she turned to what she considered the true enterprise of her life: the deep, serious business of deciphering Linear B.

Kober did not write or lecture about the script publicly until the early 1940s, but her private papers make clear that she had begun tackling it long before. “I have been working on the problems presented by the Minoan scripts … for about ten years now, and feeling rather lonely,” she wrote to Mary Swindler, the editor of the American Journal of Archaeology, in January 1941.

Where Evans’s approach to Linear B was scattershot, impressionistic, and anecdotal, from the start Kober imposed more rational methods. Her first order of business, starting in the 1930s, was frequency analysis: the creation of statistics “of the kind so successfully used in the deciphering and decoding of secret messages,” as she wrote, for every character of the script.

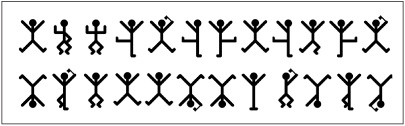

Anyone who has solved a Sunday newspaper cryptogram has met frequency analysis head-on. At its simplest, it entails pure counting, with the decipherer tabulating the number of times a particular character appears in a particular text. If the text is long enough, the frequency count for each letter should mirror its statistical frequency in the language as a whole. It was frequency analysis that let Sherlock Holmes decipher this secret message, one of several at the center of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s story “The Adventure of the Dancing Men.” (The font used here differs somewhat from the original, but the message is the same):

As Dr. Watson and a provincial police inspector look on, Holmes elucidates his method. “As you are aware,” he says, “E is the most common letter in the English alphabet, and it predominates to so marked an extent that even in a short sentence one would expect to find it most often.” To Holmes, it was immediately apparent that the character  , the most frequent in the cipher, stood for “e.” As for the rest of the alphabet, he continued, “Speaking roughly, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, and L are the numerical order in which letters occur.” (The message, quickly unraveled, read: “Elsie. Prepare to meet thy God.” Happily, Elsie did not.)

, the most frequent in the cipher, stood for “e.” As for the rest of the alphabet, he continued, “Speaking roughly, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, and L are the numerical order in which letters occur.” (The message, quickly unraveled, read: “Elsie. Prepare to meet thy God.” Happily, Elsie did not.)

Every language has its own characteristic letter frequencies, and for decipherment, this fact can be telling. In German, the eleven most frequent letters, in descending order, are e n i r s t a h d u l. In French, they are e a s t i r n u l o d. Thus, for a simple substitution cipher like the one above, a moderately skilled investigator can use frequency analysis first to identify the underlying language (assuming it is one whose letter frequencies are known) and then to crack the cipher itself.

For frequency analysis to work properly, the text of the cipher must be long enough to provide a statistically significant sample. And that, for Kober and other investigators of Linear B, was precisely the problem: Evans, resolute as ever in old age, had continued to sit on his data. In the early 1930s, when Kober first turned her attention to the Cretan scripts, the only inscriptions to which anyone had access were the tiny handful Evans had published in Scripta Minoa in 1909, plus the small set published covertly by the Finnish scholar Johannes Sundwall—the “thesaurus absconditus,” scholars called it. The two sets together totaled fewer than one hundred inscriptions, less than one-twentieth of what Evans had unearthed at Knossos.

With so little text available, how can a decipherer even begin? Kober began by looking for ghosts.

EVERY LANGUAGE GLIMMERS with sparks of earlier ones. These sparks—a word, a place-name—are the residual traces of languages spoken before, often long before, in the same part of the world. Though tiny, the sparks can illuminate a history of invasion, conquest, trade, and the wholesale movement of populations. In the West Germanic language known as English, we can discern Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain in the first century B.C. from linguistic survivals like wine (from Latin vinum) and anchor (Latin ancora) that remain in use today. We see the enduring presence of the Celts, who inhabited Britain before the Romans and for some time afterward, in place-names like Cornwall, Devon, and London. We also see the legacy of the Viking conquests of Britain toward the end of the first millennium: Many English words starting with sk-, like skill, skin, and skirt, are of Scandinavian origin. And so on.

On the same principle, as Kober knew, it should be possible to take a linguistic X-ray of a later Aegean language and discern traces of the lost language of the Minoans glinting beneath the surface. And so she began by scrutinizing a language she knew well, Classical Greek. Starting in the early 1930s, she spent several years combing Greek for survivals from a time before Greek speakers arrived in the region—words of pre-Hellenic origin.

Compiling an accurate list of these linguistic ghosts, Kober wrote in 1942, “would be of great importance to scholars who are trying to formulate the principles underlying the language or languages of pre-Hellenic Greece and of the Minoan scripts.” These survivals by themselves would not tell her what the language of the Minoans had been—she was far too sophisticated to think that. But they might begin to reveal the structure of the words of that language. In Homer alone, she wrote, the number of pre-Hellenic words ran “into the thousands.”

Among the pre-Hellenic words Kober identified in Greek were many ending in the suffix -inth (or -inthos), including merinthos, “cord, string”; plinthos, “brick” (think of the English word plinth); minthos (“mint”); and labyrinthos, the “labyrinth” itself.

Her prospects improved in 1935, when Evans published his last major work, volume 4 of The Palace of Minos. Part of the volume was about Linear B, and it included photos and drawings of previously unseen tablets. This brought the number of available inscriptions to about two hundred. To anyone who hoped to decipher the script, that was still far from ideal, but it was a start.

For Kober, the volume’s publication seemed to mark a point of no return. She had tried several times to tear herself away from Linear B, and each time found she could not. “I’ve resigned myself,” she wrote in 1942. “If I want peace, I must first finish the job, or work till someone else finishes it.” Now, at last, she could begin in earnest to compile the statistics so vital to any decipherment.

ON JULY 11, 1941, three days after his ninetieth birthday, Arthur Evans died in England, leaving nearly two thousand inscriptions from Knossos unpublished. There was little chance they would be made public anytime soon. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, he had arranged for the tablets to be hidden for safekeeping in the Heraklion Museum. In May 1941, Crete fell to the Nazis, who quickly appropriated Evans’s Villa Ariadne as their command post. At war’s end, the Greek government had no money to retrieve, clean, and catalogue the tablets; they would remain in the museum, inaccessible, for years to come.

In her first public paper on the script—presented in December 1941, five months after Evans died—Kober did little to hide her resentment. “No archaeologist, however able, can be certain of finding inscriptions, but it is clearly his duty to publish them adequately when they have been found,” she said. “This has not been done.” As a result, she explained, scholars couldn’t agree on issues as basic as how many signs Linear B contained, or precisely which signs those were. This in turn made one of the first objectives of any archaeological decipherment—compiling lists of the script’s signs and words—utterly impossible. “In the sign lists published by Evans, for instance, several signs … appear that do not occur in any known inscription, often without the slightest clue as to their use or origin,” Kober said. “Most unforgivable of all is the fact that signs actually appearing in published inscriptions do not occur in any list whatsoever.” She added, in an astringent understatement: “These inadequacies hinder us at every turn.”

At the time, only a few facts about Linear B could be stated with certainty, most established early on by Evans. The script direction (left to right) was known. Word divisions were readily apparent, and the numerical system was well understood. It was clear that Linear B was a syllabary. The script also contained a set of logographic characters, and the meaning of many of these was plain. That the Cretan scribes used separate pictograms for male and female animals was known, though scholars disagreed as to which represented which. This was also the case for the words “boy” and “girl”— and

and  —identified as a pair in 1927 by the historical linguist A. E. Cowley.

—identified as a pair in 1927 by the historical linguist A. E. Cowley.

The meaning of only one Linear B word was known with any degree of certainty. The word was  , and while no one knew how to pronounce it, context revealed its identity: It appeared regularly at the bottom of Minoan inventories, just before the tally, and almost assuredly meant “total.” All in all, it was not much to show for forty years’ work.

, and while no one knew how to pronounce it, context revealed its identity: It appeared regularly at the bottom of Minoan inventories, just before the tally, and almost assuredly meant “total.” All in all, it was not much to show for forty years’ work.

HOW DOES A decipherer penetrate such a tightly closed system? There is only one way possible, and it can be illustrated by means of a delightful puzzle from the International Linguistics Olympiad, an annual competition for high school students.

The puzzle, adapted below from one used in the 2010 contest, was created by Alexander Piperski; it involves a real writing system, known as Blissymbolics. Blissymbolics was invented after World War II by Charles K. Bliss (né Karl Blitz), an Austrian Jew who had survived Buchenwald. It is an attempt to devise a universal writing system that can be understood by speakers of any language. Blissymbolics is an example of a pure ideographic system, in which each symbol stands for an entire concept.

Here are eleven English words, numbered for reference, written in Blissymbolics:

The translations—in random order—are these:

The object is to match each symbol with the correct translation. (The general method of decipherment is described below; the full solution is revealed in the Notes on page 317.)

When one confronts a problem like this, a natural first reaction is panic: The strange symbols look utterly impenetrable. But they aren’t, as closer inspection reveals, for every clue needed to solve the puzzle lies buried somewhere within the problem itself.

From the outset, we have one great advantage over the Linear B investigators: We are dealing here with a bilingual inscription—albeit one with the translations in the wrong order. Even so, this gives us a tremendous head start. Let us begin, then, by examining the set of English words.

We see immediately that the set contains different parts of speech: nouns, adjectives, and verbs. This is the first internal clue the problem offers, and we will make use of it in the time-honored way, by counting. We arrive at this tally:

4 nouns: waist, lips, activity, saliva

4 adjectives: active, sick, western, merry

3 verbs: to blow, to cry, to breathe

These numbers may prove useful: We now know that the group of eleven Bliss symbols contains four nouns and four adjectives, but only three verbs. If we can find something that characterizes precisely three of the symbols, we may well have found the verbs. With this in mind, we turn now to the symbols themselves. At this stage, we won’t try to translate any of them, however tempting that might be. We are going to treat them as objects of pure form and nothing more.

As we study the symbols, we notice two things. First, all but one of them (No. 10) have more than one component part. This may be important, though we don’t yet know how. Second, several symbols are topped with smaller marks—a hatlike caret  or a V-shaped sign

or a V-shaped sign  . We can sort the eleven symbols on this basis:

. We can sort the eleven symbols on this basis:

3 topped with caret: Nos. 1, 6, and 9

4 topped with V-shape: Nos. 3, 4, 7, and 11

4 plain symbols: Nos. 2, 5, 8, and 10

We have now made our first major discovery. We already knew we were looking for three verbs: In the three symbols topped with carets, we may have found them. Let us tentatively designate these symbols as verbs. We still don’t know which symbol corresponds to which verb, but for the time being that doesn’t matter. The ground we have gained so far can be summarized thus:

, and

, and  = possible verbs (order unknown): “to blow,” “to cry,” “to breathe.”

= possible verbs (order unknown): “to blow,” “to cry,” “to breathe.”

Now we seem to get stuck. We are left with four symbols topped with the V-shaped mark, and four plain symbols. There is no way to tell which group contains the nouns and which contains the adjectives. Or is there? Once again, we must scour the symbols for internal clues.

If we turn back to the English translations, we notice something tantalizing. Two words in the list are clearly related to each other: the noun “activity” and the corresponding adjective “active.” They differ in only a single parameter: part of speech. It would help enormously if we could find two Bliss symbols that are alike except for one parameter.

Scanning the symbols, we find just such a pair: 4 and 10,  and

and  . One has the V-sign; the other doesn’t. One is the adjective “active,” the other the noun “activity.” The V-sign either turns a noun into the corresponding adjective, or an adjective into the corresponding noun. But which? To answer the question, we must now start to make educated guesses about the meanings of individual signs, much as Champollion guessed that the hieroglyphic

. One has the V-sign; the other doesn’t. One is the adjective “active,” the other the noun “activity.” The V-sign either turns a noun into the corresponding adjective, or an adjective into the corresponding noun. But which? To answer the question, we must now start to make educated guesses about the meanings of individual signs, much as Champollion guessed that the hieroglyphic  was meant to invoke the Coptic word “sun.”

was meant to invoke the Coptic word “sun.”

Let’s begin by examining the four characters with V-shaped tops, Nos. 3, 4, 7, and 11:  , and

, and  . If they are nouns, then they mean (in random order) “waist,” “lips,” “activity,” and “saliva.” If they are adjectives, then they mean (also in random order) “active,” “sick,” “western,” and “merry.”

. If they are nouns, then they mean (in random order) “waist,” “lips,” “activity,” and “saliva.” If they are adjectives, then they mean (also in random order) “active,” “sick,” “western,” and “merry.”

To the layman’s eye, one sign in this group leaps out: No. 11, the heart with a V-shaped top and an upward-pointing arrow. We know that Blissymbolics is an ideographic system, meant to be understood universally. In many cultures, the heart is considered the seat of emotion. Does any of the remaining English words suggest emotion?

One does: the adjective “merry.” If we assume that symbol No. 11 means “merry,” we can then forge the following deductive chain:

• If  = “merry,” then the V-sign turns nouns into adjectives.

= “merry,” then the V-sign turns nouns into adjectives.

• Therefore,  = “activity,” and

= “activity,” and  = “active.”

= “active.”

• The three remaining nouns,  , and

, and  , are (order unknown) “waist,” “lips,” and “saliva.”

, are (order unknown) “waist,” “lips,” and “saliva.”

• The two remaining adjectives,  and

and  , are (order unknown) “sick” and “western.”

, are (order unknown) “sick” and “western.”

• The verbs  , and

, and  , are (order unknown) “to blow,” “to cry,” “to breathe.”

, are (order unknown) “to blow,” “to cry,” “to breathe.”

The rest of the symbols can be unraveled in similar fashion, until the meaning of all eleven is established. It will help to note that many of the English words refer to parts of the body or bodily functions. It will also help to think about the multipart form that most of the symbols take: This form may well encode a meaning that is the sum of the individual components.

CONFRONTING THE LINEAR B inscriptions, Kober and the other analysts faced a similar deductive process, gridded up a thousandfold. But to her great disgust, most investigators persisted in looking at the problem through the wrong end of the telescope, seeking first to identify the language the Minoans spoke and only afterward to unravel the script.

Everyone, or so it seemed, had a theory about what language the tablets recorded. Michael Ventris, for instance, who had begun thinking fervently about the problem as a schoolboy, was convinced it was the lost Etruscan tongue. He clung steadfastly to the idea until weeks before his decipherment, when he was forced to contemplate a vastly different scenario. Others held even stranger notions. “It is possible to prove, quite logically, that the Cretans spoke any language whatever known to have existed at that time—provided only that one disregards the fact that half a dozen other possibilities are equally logical and equally likely,” Kober said at Yale in 1948. “One of my correspondents maintains that they were Celts, on their way to Ireland and England, and another insists that they are related to the Polynesians of the Pacific.”

Kober indulged in no such speculation, remaining firmly agnostic on the language of the script. (“I am interested,” she once said, “only in what the Minoans wrote.”) The tablets, she insisted, must be analyzed based on internal evidence alone, and the scripts must be allowed to speak for themselves, absent the decipherer’s prejudice.

“We cannot speak of language, but only of script, because the system of writing cannot be read,” she once said. “Since all we know about the language or languages of the scripts is what the graphic remains show, a thorough understanding of these written documents is necessary before any linguistic theories are promulgated. Otherwise it is impossible to avoid reasoning in a circle.”

By the mid-1930s, with two hundred inscriptions at her disposal, Kober could begin to sift the teeming mass of symbols for the kind of internal clues she sought. And so, hour by hour and symbol by symbol, she began to count.

* * *

A LANGUAGE AND a writing system are not remotely the same thing, though each impinges on the other revealingly. In any given language, sentences can be deconstructed into words, and words further deconstructed into smaller component parts. These parts occur, importantly, “in patterns of selection and arrangement,” as the anthropologist E. J. W. Barber has said. The script used to write that language will display corresponding patterns.

A simple example: In any inscription, Barber writes, “each sign bears a relation to the signs adjacent to it.” In Italian, for instance, it is permissible for s to be followed by for g at the start of a word: sforza (“force”), sfumato (“smoky”), sgraffito (“drawing, writing”; compare English graffito and its plural, graffiti). Not so in English, for no reason other than that is simply how English chose long ago to behave. As a result, certain characters will crop up side by side in certain positions in written Italian but not in written English. Tabulating such behavior helps the decipherer seeking the language of an inscription narrow the field of likely suspects.

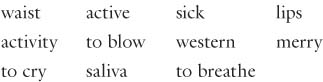

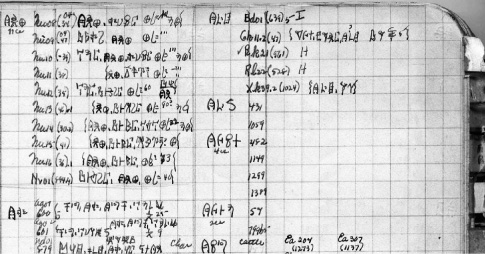

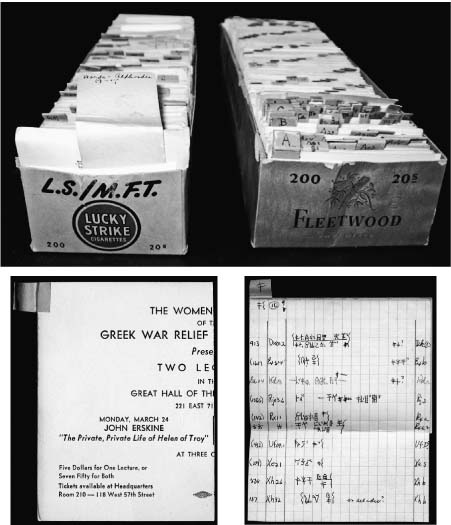

When Kober began her work, she kept her tabulations in a series of notebooks. In just a few years, she would fill forty of them—the twentieth-century account books in which she itemized the Bronze Age account books of the Minoan kingdom. But during World War II and afterward, paper was scarce, and she had to resort to enterprise (and occasional genteel larceny) to keep her statistics going. When she could no longer get notebooks, she began hand-cutting two-by-three-inch “index cards” from any spare paper she could find: church circulars, the backs of greeting cards, examination-book covers, checkout slips from the college library, and whatever else she could lay her hands on.

On the front of each card, Kober inked statistics for various signs in the minutest of writing. On the backs of the cards, bits of residual text, like fragmentary inscriptions on broken tablets, gave evidence of their original use:

Detail of a page from one of Alice Kober’s sign-juxtaposition notebooks. At upper left, she is analyzing instances in which the sign-group  is followed by other sign-groups with the same first character. Note the handmade tabs with Linear B characters down the right-hand side of the page.

is followed by other sign-groups with the same first character. Note the handmade tabs with Linear B characters down the right-hand side of the page.

Before her death, Kober would cut and annotate more than 116,600 two-by-three-inch slips, as well as more than 63,300 larger slips—some 180,000 cards in all. The smaller ones she fitted neatly into empty cigarette cartons, the one paper product of which she appeared to have no short supply. Even now, more than six decades later, to open one of them is to be met with a faint whiff of midcentury tobacco. FLEETWOOD IMPERIALS: A CLEANER, FINER SMOKE, her ersatz file cabinets say. HERBERT TAREYTON: THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT THEM YOU’LL LIKE.

A WRITING SYSTEM is a woven fabric, an interlaced network of sounds and symbols. As with real woven cloth, there are many different interlacements possible—many different ways, that is, in which sound and symbol may be bound up together. When a decipherer confronts an unknown language in an unknown script, she must hunt for a thread that, pulled, will begin to reveal the structure of the weave. She does this by searching for patterns, for every combination of language and script, as Barber writes in Archeological Decipherment, bears “a distinctive fingerprint … which may help us recognize the language involved.” It was for this reason that Kober had done fifteen years’ preparation, learning languages that employ diverse array of scripts, from logographic (Chinese) to syllabic (Akkadian) to alphabetic (Persian).

Her task would have been so much easier if only the Minoans had used an alphabet. A syllabary is far harder to decipher, because in a syllabary nearly every character stands for more than one sound. As a result, frequency counts skew very differently for syllabic scripts than they do for alphabets, and the same language will behave very differently statistically written with the one than with the other. A two-syllable word written syllabically may entail precisely two signs. Written alphabetically, as Barber notes, the same word “may be represented by from two to a dozen signs”—think of the vast difference in length between two-syllable English words like Io and strengthened.

As Kober was painfully aware, there were no published frequency tables for syllabically written languages. That is where her homemade file cards came in, helping her corral the seemingly random mass of Linear B characters into orderly statistical sets. For every word on the tablets—the two hundred published inscriptions gave decipherers about seven hundred different words to work with—she cut a separate card. On each card, in her tiny hand, she recorded as much data as she could mine about the characters it contained.

She catalogued the frequency of each character, of course, but she catalogued a great deal more than that. She noted the frequency of each character in any position in a word (initial, second, middle, next-to-last, and final); the characters that appeared before and after every sign; the chances of a given character’s occurring in combination with any other character; repeated instances of two- and three-character clusters; and much else.

In a letter to a colleague in 1947, Kober itemized the time it took her to compile a single statistic, the one that tallied a sign’s frequency in combination with others: “You can figure out for yourself how long it will take to compare each of 78 signs with 78 other signs, at 15 minutes (with luck) for each comparison. Let’s see, 78 times 77 times 15 minutes—that’s about 1,500 hours. I did it on the little slide rule I just bought to hasten the arithmetic I’ll have to do.”

After calculating her figures, Kober, using a dime-store hand punch, made holes in precisely determined spots on her cards. Each spot stood for a particular Linear B character: There was a designated spot for  , for instance, another for

, for instance, another for  , another for

, another for  , and so on. The location of each character’s hole remained constant from card to card. In this way, by stacking two or more cards together, Kober could see which holes aligned. That told her instantly which characters those words had in common. “Making all these files takes time, and the files have considerable bulk,” she wrote in 1947, “but once they are finished, all the material is so arranged that anything, no matter how unexpected, can be checked in a few minutes.”

, and so on. The location of each character’s hole remained constant from card to card. In this way, by stacking two or more cards together, Kober could see which holes aligned. That told her instantly which characters those words had in common. “Making all these files takes time, and the files have considerable bulk,” she wrote in 1947, “but once they are finished, all the material is so arranged that anything, no matter how unexpected, can be checked in a few minutes.”

What she had created, in pure analog form, was a database, with the punched holes marking the parameters on which the data could be sorted. But for all their rigor and precision, the file boxes also “reveal a gentler side to Alice Kober,” as Thomas Palaima and his colleague Susan Trombley have written. On one occasion, they note, Kober “took extra care in cutting a greeting card used as a tabbed divider, perfectly centering a fawn lying in a bed of flowers.”

ALL THE WHILE, Kober was shouldering a full course load at Brooklyn College. “I … teach in my spare time, so to speak,” she wrote with bitter humor to a colleague in 1942, and she was scarcely joking. The college was part of New York City’s public university system, and for faculty members of that period, the emphasis was on teaching rather than research. “Brooklyn College never did anything for me in a scholarly way,” Kober lamented a few years later. She shared an office with four other people (this alone would have made on-campus scholarly work impossible); in addition to her classes she was active in the customary round of university work, serving on a spate of faculty committees.

Two of Alice Kober’s cigarette-carton card files, with the ersatz “index cards” on which she sorted the characters of Linear B.

In 1943, asked to give private instruction in Horace to a blind student, Kober taught herself Braille—itself a writing system—and from 1944 onward, she brailled textbooks, library materials, and final exams for all the blind students at the college. It took as many as fifteen hours to braille a single exam.

In a letter to her department chairman in May 1946, Kober itemized her schedule for the coming weeks:

May 21–24. |

brailling examinations; preparation for a short speech to be given May 24. … Classes. |

May 25–June 6. |

Classes; braille. |

June 7. |

Examination in Latin 01; proctoring. |

June 7–10. |

Marking papers; marks due on Monday, June 10. |

June 11. |

Additional proctoring assignment in the department. |

June 12. |

Examination in Classical Civilization 1 (110 papers). Proctoring. |

June 13. |

Marking papers. |

June 14. |

Examination in Classical Civilization 10; proctoring. (30 papers). |

June 15. |

Morning—marking papers for the New York Classical Club scholarship. Evening—Phi Beta Kappa initiation. |

“The less said about teaching assignments, the better,” Kober complained to a fellow classicist in 1949. “Blankety-blank-blank will have to do. Too bad we can’t get paid for doing what we want to do.”

But with her pupils, she was warm and involved, even quietly passionate. In the early 1940s, at her students’ request, she established the Hunter chapter of Eta Sigma Phi, the national classics honor society, and was its faculty adviser. When she taught archaeology, she took her students excavating in nearby vacant lots, where they unearthed cutlery and broken dishes.

“I think I’m a good teacher, at least my students come to class with a smile, laugh at my jokes,” Kober wrote in 1947 when applying for a prestigious job at the University of Pennsylvania. Her appraisal was seconded by at least one grateful student. Among Kober’s papers is a letter she received in 1944 from a young woman in Detroit named Fritzi Popper Green:

I know that [the] name and address at the top of the page mean nothing to you. … However, my identity is not really important. I was just one of that lucky group of Latin students who, during less troublesome times some six or seven years ago, enjoyed Horace and Plautus and Terence under your capable guidance in the evening session at Brooklyn College.

I wanted you to know how much it meant to me when you carried us through so that we had sufficient credit to consider Latin our major—despite the fact that you no longer wanted to teach at night. …

I do want you to know, even at this late date, that I was one student who never believed or considered that Latin was “not practical” and that whatever love and understanding I have for the classics, I attribute, for the most part, to you.

It was clear that in her “soberly undramatic” way, Kober transmitted to her students the passion she felt for the life of the mind. Her former pupil Eva Brann remembered her telling the class, “You know a great work when the back of your neck tingles.”

IN LATE 1945, with Linear B beckoning, Kober applied to the Guggenheim Foundation for one of its coveted fellowships. If she was good enough to get it, she would have a year free from teaching for the first time in more than a decade—a blissful year alone with the script. Perhaps then she could make real headway toward the day when the ancient Cretan tablets could be read once more. It was not the content of the tablets that interested her per se, but the riddle of the script as a pure cryptographic problem. As she told the young Phi Beta Kappa initiates at Hunter that June evening, the decipherment of the Minoan tablets might not yield high drama, but to the decipherer, it would bring satisfaction of the deepest kind anyway:

We may find out if Helen of Troy really existed, if King Minos was a man or a woman, and if the Cretans really had a mechanical man who marched along the cliffs of Crete and warned the inhabitants when hostile sea-farers tried to land. On the other hand, we may only find out that Mr. X delivered a hundred cattle to Mr. Y on the tenth of June, 1400 B.C. But that is one of the hazards involved. After all, solving a jigsaw puzzle is no fun, if you know what the picture is in advance.