IN APRIL 1946, THE NEWSPAPERS announced the 132 recipients of that year’s Guggenheim Fellowships. There were luminaries on the list, including the photographer Ansel Adams, the poet Gwendolyn Brooks, and the composer Gian Carlo Menotti. Also on the list, receiving the first major award of her career, was Alice Kober. The $2,500 stipend would free her from teaching for twelve months, time she could devote without interruption to Linear B.

Congratulations streamed into Brooklyn. Sir D’Arcy Went-worth Thompson, a Scotsman who was, in Kober’s words, “one of the ‘grand old men’ of classical scholarship,” wrote her, “Your learning is great, your courage is immense, and your problem is altogether delightful.” Leonard Bloomfield, the most eminent linguist of the first half of the twentieth century, sent Kober an even more arresting tribute. He wrote: “The very notion of your problem scares me.”

Kober arranged for a year’s leave from Brooklyn College, to begin on September 1. As the foundation required, she underwent a physical exam; in light of the devastating illness that would overtake her in little more than three years’ time, it is heartbreaking to read her doctor’s report today. “I find she is in excellent physical condition,” he wrote. “There is no evidence of any organic [or] functional disease.”

Even before her fellowship began, she had much to keep her busy. She started work on a major review, for the American Journal of Archaeology, of volume 1 (there would eventually be two) of Bedřich Hrozný’s “decipherment” of Linear B. Hrozný, the decipherer of Hittite cuneiform, was determined to show that the language of Bronze Age Crete was also a form of Hittite. “It seems the sheerest balderdash,” Kober wrote privately to John Franklin Daniel, the journal’s new editor. “But Hrozný has been lucky with Hittite … so I want to consider very carefully before I make the nasty comments I feel like making.”

The more Kober considered, the more furious she grew at Hrozný’s unscientific approach to the script. “I hope he will not be too annoyed with my review,” she wrote to another colleague, “but I feel that in scholarly matters the truth must always be told.” By the time she sat down to write the review, she was so inflamed that she told Daniel he would need asbestos paper on which to print it. “Don’t cool off too much before writing your review of Hrozný,” Daniel replied cheerfully by return mail. “I have checked and find that we have a small stock of asbestos paper available.”

Daniel, a young archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania, was one of the few people in Kober’s field whom she genuinely respected. (Ventris, by contrast, was not.) In 1941, Daniel had published an important article on the Cypro-Minoan script, a Late Bronze Age writing system used on Cyprus and thought to have been derived from Linear A. He and Kober began corresponding in the early 1940s, after Daniel succeeded Mary Swindler as the AJA’s editor; by the middle of the decade, he would become the most important person in Kober’s professional life.

The months before her fellowship also let Kober expand her linguistic repertory in preparation for Linear B. She had long since mastered a host of languages ancient and modern: Greek and Latin, of course, as well as French and German, all standard issue for a working classicist, plus Anglo-Saxon. Starting in the early 1940s, she had set about learning Hittite, Old Irish, Akkadian, Tocharian, Sumerian, Old Persian, Basque, and Chinese. From 1942 to 1945, while teaching full-time at Brooklyn, she commuted weekly by train to Yale to take classes in advanced Sanskrit. She knew far better than to expect to find any of these languages lurking in the tablets. What she was doing, as she made clear in her correspondence, was arming herself with them “against the happy day when they may do me some good.”

Kober had also prepared by studying Old and New World field archaeology: In the summer of 1936 she took part in an excavation in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico; in the summer of 1939, she explored ancient sites in Greece. Years later, she would write of being “homesick for Athens,” wistfully recalling “my scrambles up and down the north slope of the Acropolis.”

She did manage a vacation of sorts before her fellowship began, driving with friends through the American West and down into Mexico in the summer of 1946. (Her brief account of the trip is one of only two passing references to social life in her entire archived correspondence, which comprises more than a thousand pages.) But as a letter she wrote to Daniel mid-voyage, on hotel stationery from Boulder, Colorado, indicates, she took Linear B along.

It was so like Kober to do two things at once, squeezing as much as she could from every available moment. For relaxation, she occasionally knit, or read detective stories. Unlike most people, however, she did them simultaneously. The mathematical elegance of each pursuit must have appealed to her greatly, as did the possibility of their efficient combination.

ON SEPTEMBER 1, 1946, Kober’s Guggenheim year officially began. She spent the first several months “clearing up the background,” as she called it—analyzing more Asia Minor languages like Lydian, Lycian, Hurrian, Hattic, and Carian “and some remnants of others.” Many of these had no published word lists available, and she had to make card files for each language from scratch. “It’s a thankless job, and most scholars wouldn’t undertake it,” she wrote Daniel that fall. “As a result, every person working in the field must do all the work over again.” For Lydian alone, she said, it took “about a month of extremely intensive work” just to set up her files.

Nonetheless, her joy in the freedom from teaching was palpable. “I had never before been able to work uninterruptedly for such long periods,” Kober wrote in a progress report for the Guggenheim Foundation in December. “It takes about a month to do what was formerly a year’s work.” In closing, she added, “I only hope my results equal my gratitude.”

To a great extent, those results would depend on the reply to a letter she had written the month before, in November 1946. A model of diplomacy, yet shot through with barely concealed yearning, it was something she had been steeling herself to compose for some time.

The letter was to Sir John Linton Myres, a distinguished archaeologist at Oxford University. Forty years earlier, Myres had been Evans’s young assistant at his excavations of Knossos. After Evans’s death in 1941, Myres inherited from him the mantle of grand old man of Aegean prehistory. Unfortunately for all concerned, he also inherited Evans’s work on Linear B, and it was he who was charged with putting four decades of notes and transcriptions into publishable shape. Evans, as Andrew Robinson observes in The Story of Writing, had left “a disorganized legacy.” His planned second volume of Scripta Minoa, devoted to Linear B, never materialized in his lifetime. The thankless task of producing it now fell to Myres, who by the mid-1940s was elderly and ill himself.

When Kober wrote to him, scholars still had access to only two hundred inscriptions. Myres had Evans’s transcriptions and photos of nearly two thousand more: Evans had decreed that they were to remain unseen until Scripta Minoa II was published. If Kober could see them privately beforehand, her store of inscriptions would increase almost tenfold. But knowing Evans’s desire for control of his material—even, it would seem, from beyond the grave—she held out little hope.

“Dear Professor Myres,” she wrote on November 20, 1946:

This letter is an extremely difficult one to write because I have a request to make which I fear cannot be granted. Yet, under the circumstances, it is necessary for me to ask. …

If it is in any way possible for me to see some, or all, of the unpublished inscriptions during the year when I am free to devote all my time to them, it would be of great advantage to me, and perhaps would speed the ultimate decipherment. …

I had hesitated to impose the request upon you, because I know publication of the Corpus is under way, and although it is now over fifteen years since I began working on the problem, I have always felt that Sir Arthur Evans should be the one to decipher the scripts, since he was the one to whom we owe the knowledge of their existence. If it was his wish that no one should see the unpublished inscriptions until they were formally published under his auspices, I cannot help but agree that he deserves that tribute to his memory.

Since, however, scholarly interest sometimes resembles religious fanaticism in its demands, I feel I must ask you whether I could see the unpublished material during my year of freedom from academic duties. …

In closing, she wrote, with characteristic quiet ardor, “I must confess, strong as the statement sounds, that I would gladly go to the ends of the earth, if there were a chance of seeing a new Linear Class B inscription when I got there.”

She signed the letter, “Apologetically, yet hopefully, (Miss) Alice E. Kober.” Then she settled down with her cigarettes and her slide rule to wait for an answer.

BY THEN, KOBER—working with only two hundred inscriptions— had already taken a significant step forward. The thousands of hours spent sifting her cards had begun to pay dividends, and, piece by piece, the picture on the puzzle box was starting to emerge. In 1952, in his triumphant announcement of the decipherment on BBC Radio, Michael Ventris discussed the steps by which a decipherer makes his way through the forest of symbols:

The usual way of putting the signs of a syllabary into some standard order, when we know how they are pronounced, is to arrange them on a syllabic grid. … The most important job, in trying to decipher a syllabary from scratch, is to try to arrange the signs provisionally on a grid of this sort, even before we can work out the actual pronunciation of the different vowels and consonants. … Once we can determine, later on, how only one or two signs were actually pronounced, we can immediately tell a good deal about many other signs which lie on the same columns of the grid … and it can only be a matter of time before we hit on the formula which solves it.

What Ventris did not say was that it was Alice Kober, at her dining room table, who had first done those very things.

In 1945, Kober published what would be the first of her three major articles on Linear B. Her great contribution to the decipherment—elegantly on display in all three papers—lay not only in what she found but also in the means by which she found it. Several things about her method stood out:

To begin with, she assumed almost nothing, disregarding nearly every idea about the script that had been put forward by others. (Practically the only thing Kober did not doubt was that Linear B was a syllabary. “If all the Minoan scripts aren’t syllabic, I’ll eat them,” she wrote privately. “That’s the one thing I’m sure of.”) Second, she refused to speculate on the language of the tablets. Third—and this was the most radical departure of all—she refused to assign a single sound-value to the Linear B characters.

One of the greatest temptations an archaeological decipherer faces is to assign a phonetic value to every character at the start—to speculate, that is, on which sounds of the language the various characters stand for. With an unknown language in an unknown script, there is little way to do this besides random guesswork. The great danger of doing so, as Kober repeatedly warned, is that it sets up a cycle of circular reasoning: The characters of a script correspond to the sounds of Language X; therefore, the script writes Language X.

To Kober, assigning sound-values at the outset was the refuge of the careless, the amateurish, and the downright deluded. By contrast, she treated the symbols of Linear B as objects of pure form, looking for patterns that might lead her, all by themselves, into the structure of the Minoan tongue. In the Blissymbolics problem above, we began with form and meaning: the curious symbols and the set of English translations. In Linear B, investigators faced a far more brutal situation: They were forced to inhabit, as Kober evocatively wrote, a world of “form without meaning.” Of all the would-be decipherers, she was the one most willing to dwell there for as long as it took.

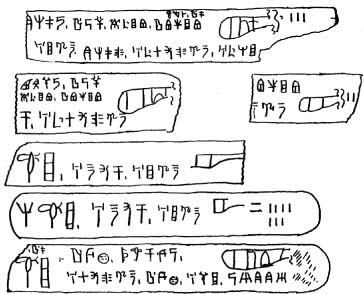

Methods like these inform all of Kober’s writing about Linear B. They come to full flower in her three important papers on the script, published in the American Journal of Archaeology between 1945 and 1948. In her 1945 paper, “Evidence of Inflection in the ‘Chariot’ Tablets from Knossos,” she examined a series of tablets, reproduced by Evans in The Palace of Minos, that deal with chariots and their constituent parts. (The “Chariot” tablets are noteworthy among the Knossos tablets for containing complete sentences of the Minoan language rather than mere word lists.) The tablets in question, as hand-copied by Kober from Evans’s book, included these:

Kober’s paper was significant for two things, both of which would have a profound effect on the course of the decipherment. First, it showed that it was possible to analyze the Cretan symbols without attaching sound-values to them. Second, it proved that the language of Linear B was inflected—that is, that it relied on word endings, much as Latin or German or Spanish does, to give its sentences grammar. Though on its face this discovery may look like a small find, it would eventually furnish the long-sought “way in” to the tightly closed system of Linear B.

Roughly speaking, inflections are word endings, also known as suffixes. Languages make use of inflection to varying degrees: In English, inflections include -s (which indicates a third-person singular verb); -ed (past tense); -ing (participle); -s (again, this time indicating a plural noun); and a few others. Modern English has only about eight inflections. Other languages, like Chinese, have almost none.

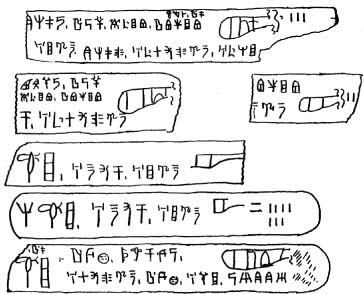

Some languages, however, use far more, as anyone who has sweated over Latin, with its constellations of word endings, can attest. In Latin, verbs can be inflected for a spate of grammatical attributes, including person (first, second, or third person) and number (singular or plural), depending on who is performing the action of the verb. Tiny but powerful, these inflections impart the kind of information that in English usually requires extra words. Consider the Latin verb laudāre, “to praise.” When any of the following suffixes is attached to its stem (laud-), the result is an entire small sentence, elegantly bound up in a single inflected word:

The nouns of Latin are also richly inflected. In the table below, inflections mark the noun’s “case,” telling us what role it plays in a given sentence: subject, direct object, indirect object, possessor, or addressee:

For the analyst of an unknown script, demonstrating that the language of the script is inflected is a major diagnostic triumph, for it narrows the field of likely candidates in a single stroke: One can immediately eliminate inflection-poor languages like Chinese and focus the search on inflection-rich ones like Latin. But there is a catch: Conclusive proof of inflection is extremely hard to come by—much harder than it seems.

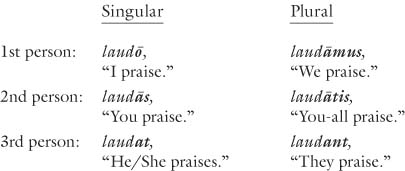

When Evans first studied the Knossos tablets, he noticed small sequences of symbols that seemed to recur at the ends of words. Among them were these:

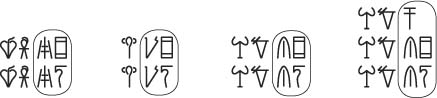

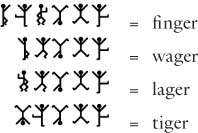

He decided that these sequences were inflections on the ends of Minoan nouns. (He thought they indicated gender, or perhaps case, much as suffixes on German and Latin nouns do.) But inflections are wily things, and it is all too easy for an investigator to spot them where they don’t actually exist. Consider the following four English words, written in the Dancing Men font to make them more cipherlike:

A decipherer will immediately spot the three-character sequence  at the end of each word. It certainly looks like a suffix, perhaps -ing. “Eureka! Inflection!” he cries. But is it really?

at the end of each word. It certainly looks like a suffix, perhaps -ing. “Eureka! Inflection!” he cries. But is it really?

Deciphered, the four words turn out to be these:

Here, “inflection” is a false friend, for as any English speaker knows, there is no suffix -ger in the language; nor are there stems fin- (in this sense), wa-, la-, or ti-. The repeated pattern at the ends of these words is mere coincidence and nothing more.

Had Evans truly found inflection in Linear B, or had he been similarly seduced? Though he wrote of his little paradigms, “We have here, surely, good evidences of declension” (that is, inflection on the ends of nouns), his discovery was intuitive and circumstantial, and had to be taken on faith. Kober knew that for the decipherment to advance, someone had to prove conclusively whether or not the Minoan language was inflected. This she set out to do.

If you are studying an unknown language in an unknown script and you see what looks like inflection, how do you prove it actually is inflection? For Kober, the answer was to be found in the “patterns of selection and arrangement” that had emerged over the years as she pored over her cards. She had let the tablets speak for themselves and now they were beginning to reward her.

“If a language has inflection, certain signs are bound to appear over and over again in certain positions of the written words, as prefixes [or] suffixes,” she wrote in her 1945 article. “No matter how much these changes may be obscured, the fact that they occur regularly must reveal them, if the amount of material available for analysis is large enough, and the analysis sufficiently intensive.”

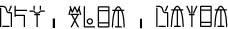

As she studied the “Chariot” inscriptions, Kober noticed certain words, and even phrases, that recurred on two or more tablets. Among them was the word  , which appeared on two tablets;

, which appeared on two tablets;  , which appeared on three; and

, which appeared on three; and  , found on five. She also identified an entire three-word phrase:

, found on five. She also identified an entire three-word phrase:  , which was repeated on five different tablets.

, which was repeated on five different tablets.

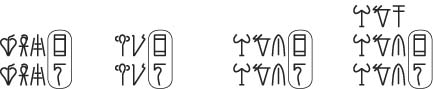

Strikingly, Kober also found words that recurred in similar but not quite identical forms—forms that differed only in their last few characters. The words seemed to have the same stem but different suffixes. They included  and

and  (where the stem starts with

(where the stem starts with  );

);  and

and  (where it starts with

(where it starts with  ); and

); and  and

and  (where it starts with

(where it starts with  ).

).

It was also significant, as she noted, that a variety of Minoan endings could combine with a variety of stems, a defining property of suffixhood. (In English, for instance, the suffixes -er and -ing can attach to a wide array of stems, including sing-, teach-, and work-. They cannot, by contrast, attach to “pseudo-stems” like wa-, la-, and ti- above.)

A similar process, Kober showed, could be seen on the Linear B tablets. The suffixes - and -

and - , for instance, could combine not only with the stem

, for instance, could combine not only with the stem  , but also with other stems, as attested by the presence of word pairs like

, but also with other stems, as attested by the presence of word pairs like  and

and  ;

;  and

and  ; and

; and  and

and  . Strikingly, although Kober had not set out looking for them, the suffixes -

. Strikingly, although Kober had not set out looking for them, the suffixes - and -

and - , which she found so often at the ends of Linear B words, were also the ones Evans had instinctively noted:

, which she found so often at the ends of Linear B words, were also the ones Evans had instinctively noted:

What Kober showed was not merely that these suffixes alternated in Linear B words, but also that they alternated in regular fashion, attaching to the same range of stems, just as -er and -ing do in English. “It was one thing to suggest that the writing on the Linear B tablets might conceal an inflected language,” Maurice Pope wrote in The Story of Archaeological Decipherment. “It was quite another to establish definite patterns of inflection. This is what Miss Kober did.”

It was a pathbreaking discovery, and it accomplished several things. For one, it narrowed the field of possible candidates for the language of the tablets. For another, it settled one vexing problem immediately: the question of whether the languages of Linear A and Linear B were the same. It was clear that the Linear B script had developed from the earlier Linear A; on that, scholars could agree. But were the languages they wrote also related? Most investigators, including Evans and Ventris, believed they were.

But to Kober, the data told a far different story. Her preparation had also included careful study of the published Linear A inscriptions, and none of them showed evidence of inflection. The conspicuous presence of inflection in Linear B, and its conspicuous absence in Linear A, convinced her that the respective languages were different. Hers was the minority view, but one to which she held firmly.

Finding inflection in Linear B would lead Kober to even deeper discoveries about the script, which she would publish toward the end of the 1940s. These discoveries centered on the very particular things that happen when an inflected language is written with a syllabic script. This critical interaction, she showed, can offer vital clues to the nature of the language in question. She hinted as much in 1945, in a telling footnote to her first major paper:

“When a syllabary is used [inflections] are bound to be obscured,” she wrote, “since even the simplest syllabary consists of signs that combine a consonant and vowel, so that even a slight inflectional alteration may produce a word spelled with entirely different signs.” It was this observation, more than anything else, that would be the linchpin of the decipherment.

ON DECEMBER 13, 1946, a letter with an Oxford return address arrived at Kober’s home. She let an hour go by before she dared open it. When she did, she was astounded: Sir John Myres had granted her request to see the Knossos inscriptions. “Please let me know your plans and let me know how I can further them,” he wrote. “The whole material is in my control.”

“I cannot tell you how happy your letter made me,” Kober wrote him in reply. “My fondest hopes [have] materialized.” But as things played out, getting access to the inscriptions was both the best and the worst thing that could have happened to her.