. She called this ending Case I. The nouns appearing in Case I included these:

. She called this ending Case I. The nouns appearing in Case I included these:IN A LITTLE OVER A month, I’ll be in the same town with the Scripts,” Kober wrote rapturously to Myres in early February 1947. She had just booked her passage by sea—she was somewhat afraid to fly—and would sail from New York in March. On arriving in England, she would travel by train to Oxford, where she would live at St. Hugh’s, one of the university’s women’s colleges.

In the meantime, some arduous preparation lay in store for her. Kober would have just five weeks in Oxford—five weeks in which to copy nearly two thousand inscriptions from Evans’s photographs and drawings. To make matters more difficult, she would have to copy everything by hand: the ubiquitous office photocopier was years in the future. As she must have felt keenly, when it came to the efficient duplication of written text by a lone copyist, the techniques available to scholars in the mid-twentieth century had not advanced much beyond those employed by the Cretan scribes three thousand years before.

What techniques there were tended toward the shoddy. Kober’s hand-cut index cards testify to the continued scarcity of paper years after the war ended; the little that could be had was usually substandard. Several times in her correspondence of the late 1940s she vents her frustration at the available paper, which was of such poor quality that it would barely take ink. Things were even worse in Europe, which long after the war remained beset by severe shortages. In a letter written in June 1947, after her return from England, Kober described the conditions she encountered there:

It was quite bearable for a short-term visitor like me. It’s different for the people who live there, and have had it for seven years. One of the tutors at St. Hugh’s spent a week of her Easter vacation reweaving the elbows of her only decent tweed jacket. Sir John uses the gummed paper of the blank strip on the outside of a page of stamps to cover errors and changes in the ms. he’s getting ready to publish. He can’t get erasers or ink eradicator. I left him everything I could in the way of writing equipment. He protested very feebly, and ended by saying the things would be “most welcome.” All this in one of the countries on the winning side.

Acutely aware of these conditions, Kober spent the late 1940s sending care packages to overseas colleagues she’d never met, in a one-woman campaign to ameliorate postwar shortages. Her efforts recall those of Helene Hanff, whose epistolary memoir, 84, Charing Cross Road, recounts her doing likewise for the staff of a London bookshop.

One of Kober’s regular beneficiaries was Johannes Sund-wall, the Finnish scholar who had dared defy Evans by publishing some of the Knossos inscriptions. Of all the people working on the problem, Sundwall was the one Kober respected most. His approach to the decipherment was of a piece with her own: cautious, scientific, and thorough. He was a good deal older than she; when they began corresponding, in early 1947, she was forty, he about seventy. Though they would never meet, her letters to him—warm, charming, forthcoming, and uncharacteristically girlish—suggest that Sundwall became a cherished intellectual father figure, one of the few people in the world besides John Franklin Daniel by whom she felt truly understood.

Kober had long admired Sundwall’s work from afar: It had been impossible to contact Finland during the war. As a result, she was quite unprepared for the letter that arrived at her home in January 1947. “Dear Miss Kober,” Sundwall wrote, “I have read your papers on the Knossian tablets and … wish to compliment you on your methodical treatment of the most intricate problem that is met with in the Ancient History. … I am very glad that you are interested in these problems and hope for collaboration on the [most] interesting and difficult problem of decipherment.”

Her reply has the ardor of a schoolgirl who had just received a letter from a favorite film star. “Of all the people in the world,” she wrote, “you are the one with whom I have most wanted to correspond. For that very reason, I have been afraid to write. Before the war, it was because I didn’t think I had anything to say worthy of your attention, and since then … because I didn’t have your address. … I have carefully laid aside a copy of each article I did write (there are only two so far) to send you when the war was over.”

Besides sending Sundwall her articles, Kober would send him many parcels. One, as she wrote in an accompanying letter, contained “coffee in the bean and some soluble coffee called Nescafé”—and here, on the typewritten page, she has carefully drawn in the acute accent on the final e by hand—“which is not as good, but lasts longer, although the jar must be kept closed, because it attracts moisture from the air and becomes as hard as stone if one is not careful.” On another occasion she mailed him an orange, which she had coated in wax so it could withstand the journey. On a third, she made up a package of Nescafé, sugar, oranges, and rum chocolates, writing, in German, the mutual language in which Sundwall felt most comfortable, “Höffentlich sind Sie nicht Teetotaler (kennen Sie das Wort?)”—“Hopefully you’re not a teetotaler (do you know the word?).” After a grateful Sundwall sent her a photograph of himself imbibing one of her gifts, she replied, almost coquettishly: “Mother and I decided it was a picture of you drinking Nescafé, and were delighted when your letter confirmed our guess. Are you sure you haven’t made a mistake of about twenty years in your age? After seeing that picture, I am sure you are no more than fifty.”

Sundwall’s publication of the contraband inscriptions in the 1930s had helped Kober greatly: Without them, she would not have had enough material for even preliminary conclusions. Now, a later book of Sundwall’s, Knossisches in Pylos, which contained additional inscriptions, would prove a huge boon. It was published in Finland in 1940, but Kober was able to get a copy only in 1947, after searching for more than a year. When it arrived, as she later wrote, she “spent two very happy days … copying the inscriptions.”

The book also played a role in her rigorous preparation for her trip to England. Because she was under pressure to copy as many inscriptions as possible in her brief time in Oxford, she spent the weeks before her departure training for the task like an athlete preparing for the Olympics. Using the inscriptions in Sundwall’s new book as test material, she put herself through rigorous time trials at the dining table. “I’ve timed myself,” she wrote Myres in February 1947, “and think I can copy between 100–125 inscriptions in a twelve-hour day.”

What might have made more sense, though, as she acknowledged, was practicing when her fingers were stiff with cold: Myres had warned her that indoor temperatures throughout Britain were almost unbearably low, a consequence of the continuing fuel shortage.

“[Myres] mentions having a ‘severe chill’ in every letter, and is apparently confined to his room, not only because of illness, but probably also because of the lack of fuel,” she wrote John Franklin Daniel in February. “I feel guilty at the thought that I can work in a nice warm house here. I remember only too well what it was like to try and work when the best temperature our fuel ration permitted was 60 or 55.”

By March 6, the day before she sailed, Kober had reached a state of hopeful pragmatism. “I’ll be content to copy what I can,” she wrote to Myres that day. “Ploughing through snow, or wading through rain, March 13 will see me at Oxford, and happy to be there.”

On the seventh, armed with writing materials and warm clothing, Kober boarded the Queen Elizabeth for the six-day passage to England. She planned to learn Ancient Egyptian on the boat trip over.

* * *

ONE THING KOBER did not bring along was the mountain of publications about Linear B that had sprung up in the half century since Evans unearthed the tablets. “Everything that’s been written on Minoan is in my files—and much of it is completely worthless,” she had written Myres before she left New York. “The useful things I know practically by heart.” What she was too modest to add was that the single most vital contribution published so far was a paper of her own—the second of her three major works—which had just appeared in the American Journal of Archaeology.

The article was officially published in 1946, although the issue that contained it, delayed by postwar printing problems, did not actually come out until 1947, just before Kober left for England. Titled “Inflection in Linear Class B,” it picked up where her first major article, from 1945, had left off.

In the earlier paper, Kober had shown that the Minoans spoke an inflected language. Now came the real payoff from that demonstration: In a discovery that would have enormous implications for the decipherment, she now homed in on precisely what happens when an inflected language is written in a syllabic script. As a result, the complex interlacements between the Minoan language and the Minoan writing system could start to be untangled.

It was Kober’s most dramatic advance so far, and there were three actors in the drama. The first were the stems of Minoan words, analogous to English stems like the noun kiss-. The second were the suffixes attached to Minoan words, like -es in the plural noun kisses. The third was the Linear B character that bridged the gap between stem and suffix. (If English were written syllabically, a single character—representing “se”—would be used to write the last consonant of kiss plus the first vowel of -es in the inflected word kisses.)

Whenever a syllabic script writes an inflected language, these three actors assume a very particular relationship. The relationship is deceptive by nature: It produces a weave that looks hard to unravel but that actually, once only a few sound-values are known, can be picked apart quite easily. In her 1945 paper, Kober had illustrated this relationship with a hypothetical example from Latin, using the verb facere, “to make,” whose perfect-tense stem, fec-, can be combined with a variety of endings:

Let us suppose, for instance, that Latin was written in a syllabary … (with separate signs for the five vowels, and all the other signs representing a consonant and vowel combination), and that we know nothing about either the language or the script used. We find two very similar statements, one ending in the word fecit [“he made”], the other in the word fecerunt [“they made”]. We would have no way of telling that the words were related, since only the initial sign (fe) would be the same for the two words. It would be necessary, before any further progress could be made, to discover in some way that the signs for ci and ce had the same consonant. After that fact had been established, there might be enough material to show that the sign for t and the sign for runt alternate with sufficient regularity to permit the supposition that they are inflectional variations.

In her 1946 paper, Kober expanded decisively on this idea. To read it is to feel the back of one’s neck tingle.

As scholars knew, most Minoan words were three or four characters long. Now Kober trained her sights on one pivotal character—usually the third character in a given word. This character linked the stem of a Minoan word with its suffix, just as the se of kisses does in our imaginary English syllabary. It would come to be known as the “bridging” character, and it would prove crucial in the decipherment.

To show how bridging characters work, Kober looked at the stems of several Minoan nouns. (As she explained, one could reliably spot the nouns of Minoan without being able to read Minoan: Since many of the tablets were inventories, it was a safe bet that each item in a list—“man,” “woman,” “goat,” “chariot”— was a noun. It was equally safe to assume that with rare exceptions, all nouns in a given list shared the same grammatical case.)

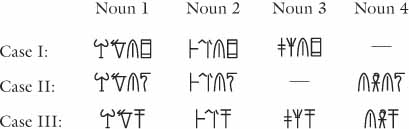

As she studied her nouns, Kober spotted eight that had a common ending: - . She called this ending Case I. The nouns appearing in Case I included these:

. She called this ending Case I. The nouns appearing in Case I included these:

and

and

Elsewhere on the tablets, she spotted the same stems with a different ending, - . This she called Case II. The words now looked like this:

. This she called Case II. The words now looked like this:

and

and

She found these stems with still another ending, the one-character suffix - . This she called Case III:

. This she called Case III:

and

and

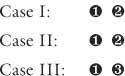

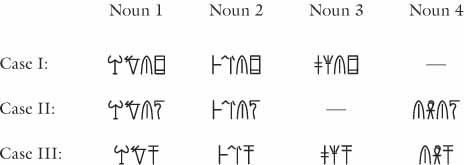

From these three cases, Kober built a paradigm. Not every noun could be found in every case on the tablets, but she seeded the paradigm with as many examples as she could. Michael Ventris would waggishly name these trios of related forms “Kober’s triplets”:

Kober homed in on the “spelling change” that affects the third character in each word. In Cases I and II the third character is  , but in Case III it becomes

, but in Case III it becomes  . What, she wondered, accounted for the change?

. What, she wondered, accounted for the change?

The changeable nature of this character, Kober realized, signified much. This was the “bridging” character—the link between a word’s stem and its suffix. As such, it comprised a piece of each: the last consonant of the stem plus the first vowel of the suffix—a single character that does the work of se in kisses. To illustrate this character’s role, Kober again turned to a hypothetical example from Latin, this time involving the noun stem serv-, “slave.” Here serv- is shown in three different cases (servus, servum, and servo), with the hyphen marking the boundary between stem and suffix:

Case I (nominative): serv-us |

“the slave” (subject) |

Case II (accusative): serv-um |

“the slave” (direct object) |

Case III (dative): serv-o |

“to/for the slave” (indirect object) |

Suppose we expand on Kober’s example by imagining once more that Latin were written with a syllabic script. The three cases of serv- might then be divided into chunks as shown below. It is important to note that when the words are written syllabically, the final -s of servus is missing, as is the final -m of servum. There is a reason: Syllabaries like Linear B—in which each character stands for one consonant plus one vowel—are bad at representing final consonants, and often simply delete them.

Here are the three words, written syllabically. This time, the hyphen indicates the boundary between syllables:

Case I: ser-vu

Case II: ser-vu

Case III: ser-vo

Our little paradigm contains just three distinct syllables: “ser,” “vu,” and “vo.” We can drive Kober’s point home graphically by creating a three-character syllabary with which to write them; I have arbitrarily chosen  ,

,  , and

, and  as the characters in our tiny syllabic script. The three syllables will now be rendered this way: “ser” =

as the characters in our tiny syllabic script. The three syllables will now be rendered this way: “ser” =  ; “vu” =

; “vu” =  ; “vo” =

; “vo” =  .

.

Rewritten in the syllabic script, our little paradigm looks like this:

Notice what happens in the switch from alphabet to syllabary. We see, correctly, that the three words share their initial syllable, represented by  . But we also see—wrongly—that the second syllable of Cases I and II is identical, written with

. But we also see—wrongly—that the second syllable of Cases I and II is identical, written with  each time. Now look at the paradigms side by side:

each time. Now look at the paradigms side by side:

With an alphabet, the difference between servus and servum is plain. With a syllabary, it is completely obscured: Both are written  .

.

Our syllabary deceives us in other ways. The alphabet tells us that in all three words, the second syllable starts with the same consonant: “vus,” “vum,” “vo.” The syllabary lies about this fact. Now two different characters,  and

and  , are used to write that syllable, depending on the word’s case. This “spelling change” from

, are used to write that syllable, depending on the word’s case. This “spelling change” from  to

to  is crucial:

is crucial:  and

and  are the “bridging” characters, representing both the last consonant of the stem and the first vowel of the suffix. The character changes because the vowel of the suffix (“vus” and “vum” in Cases I and II; “vo” in Case III) has changed.

are the “bridging” characters, representing both the last consonant of the stem and the first vowel of the suffix. The character changes because the vowel of the suffix (“vus” and “vum” in Cases I and II; “vo” in Case III) has changed.

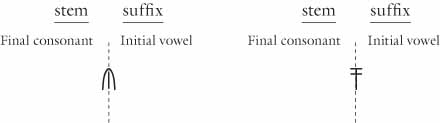

To visualize the role of bridging characters in a “science of graphics,” one must mentally split them down the middle, like the contested baby in the King Solomon story, with each “half” claimed by a different syllable:

This, Kober realized, was precisely what caused the change in the third syllable of the nouns in her paradigm, repeated here:

It was as though these “bridging” characters, too, had been split down the middle, incorporating the end of the stem and the beginning of the suffix in equal measure. This accounted for the change in spelling from  to

to  in Case III:

in Case III:

This one-character bridge may look like a small thing. But in isolating its function, Kober had taken an immense step forward. “If this interpretation is correct,” she wrote in her 1946 paper, “we have in our hands a means for finding out how some of the signs of the Linear Class B script are related to one another.” In the example above, for instance, we can tell instantly that  and

and  share a consonant but have different vowels, just as the Latin syllables “vum” and “vo” do.

share a consonant but have different vowels, just as the Latin syllables “vum” and “vo” do.

With a foot in one syllable and another in the next, bridging characters were the linchpins of Minoan words. By identifying and describing them, Kober had found a way of establishing the relative relationships among the characters of the script without having to know any of their actual sound-values. And on this linchpin the decipherment would turn, although she would not live to see it.

ON MARCH 13, 1947, when Kober arrived in England, she immediately regretted not having practiced copying with stiffened fingers. It was even colder there than she had expected: She had arrived at the tail end of the brutal winter of 1946–47, famous even now in the annals of British weather. “I’ve been devoting all the time available to copying Minoan inscriptions, sometimes a more difficult job than you’d think, when the room temperatures hover around forty degrees,” she wrote Henry Allen Moe, the secretary of the Guggenheim Foundation, from Oxford in early April.

Having access to so much data was a decidedly mixed blessing. On the one hand, if she could copy it all in her five weeks in England, her store of available inscriptions would increase tenfold. On the other, it would mean that she would have to start her painstaking analytic work all over again. It had taken her five years just to analyze the two hundred inscriptions she already had.

Despite the spartan conditions, Kober reveled in British university life. “I had a most delightful time, staying at St. Hugh’s College as a sort of honorary member of the Senior Common Room, and finding out what life at Oxford was really like from the inside,” she wrote John Franklin Daniel afterward. “Everybody was so nice, I’ve come back with a severe case of swollen head.”

She, in turn, had nothing but praise for Sir John Myres. “He says what he thinks, firmly, decisively, and oh, so politely,” she wrote after her trip. “I can hardly realize I have seen him for only six weeks, once. He is a wonderful man.”

Myres let her copy whatever she wanted from Evans’s trove of inscriptions, with one proviso: She was to publish nothing based on the material until Scripta Minoa II came out. This did not discourage her. The book was due out in early 1948, less than a year away. It would take her at least that long to analyze the welter of new data.

Kober left England on April 17. Before she sailed, she offered to help Myres prepare the manuscript of Scripta Minoa II for publication. The sooner the volume was out, she reasoned, the sooner she would be able to make her own discoveries known to the scholarly public.

ON APRIL 25, when the Queen Elizabeth docked in New York, it brought Kober home to an ocean of work. “I have so much to do, I hardly am aware that spring is coming,” she wrote to Daniel shortly afterward. “My trip to England was successful beyond my wildest dreams—in fact, too successful, since Sir John insists that I go to Crete to check the originals of the Knossos inscriptions for him, and I don’t know how the President of Brooklyn College will feel about my running off in the middle of the next semester.”

A few months earlier, knowing how much time it would take to analyze the Oxford data, Kober had requested a renewal of her Guggenheim Fellowship. Her letter to Henry Allen Moe, from January 1947, offers a masterly account not only of her approach to the decipherment but also of her willingness to forsake security for science:

“Dear Mr. Moe,” she wrote:

After a long debate with myself, I finally decided to request the renewal of my Fellowship for another year. The chief reason for my hesitation was that, since Brooklyn College cannot be expected to give me any assistance during a second year of leave, my financial situation will be precarious. It seems to me, however, that at this stage of my work it would certainly be selfish for me to put any personal considerations in the way of a possible successful result. …

The reason I feel compelled to ask for more time is the unexpected, but very welcome, permission given me by Professor Myres to go to England and see the unpublished Minoan inscriptions.

According to report, the total number of inscriptions found by Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos was about 2000. Of these, some 200 have been published. … I think (and since my work so far has proceeded according to schedule, my estimates seem to be fairly accurate) that it will take about a year to bring the new material into conformity with the old. …

Perhaps I had better explain what the process of classification is. Most scholars seem to work with only two files, one in some kind of pseudo-alphabetical order (the system of writing, it must be remembered, is still unknown, and an artificial order has to be set up), the other in reverse, beginning with the end of the word. While these files are essential, they are not enough. One reason why I have been able to do more with the Minoan scripts is because my files contain more. I use, in addition to the two just mentioned

1—a word file, in which enough of the context is set down to show the use of the word

2—two sign-juxtaposition files, one listing every sign used according to the sign that precedes it, the other according to the sign that follows it. These files are the basis for further analysis of possible word roots, suffixes and prefixes.

3—a general file, in which any two signs appearing together in a word are listed, whether they are juxtaposed or not. This file is needed in order to check … signs which alternate with one another in certain positions.

Other, more complicated files are built up when the inflection system becomes apparent, but their exact nature cannot be predicted in advance. …

Two theories I had in September have now reached the stage of practical certainty. One is that the three different types of Minoan script, Linear Class A, Linear Class B and the Hieroglyphic-Pictographic, seem to record three different languages. The other is that Linear Class B was a strongly inflected language. I have apparently reached the stage where I can predict certain inflectional variations. …

It seems fairly safe to say that, with the new material, the inflection system, at least of nouns, should become quite apparent. In that case, it should be possible to assign phonetic values to the signs with a reasonable degree of accuracy. Decipherment will then depend on whether the language turns out to belong to a known or unknown linguistic group.

If I have another year, I think I can promise that by September, 1948, I will know whether early decipherment is possible. … I have reached exactly the right stage in the work to get the maximum benefit from the new inscriptions.

She closed the letter, “I will be content with whatever decision is made.”

The decision reached Kober in England at the end of March 1947: Her application had been denied. The letter from the foundation gave no reason beyond the generic one, that the number of applicants far exceeded the funds available. It seems fair to assume, though, that her constitutional caution, and correspondingly slender record of publication (just the kind of tangible evidence grant-givers like to see), had at least something to do with it.

Characteristically, she made the best of it. “I am in a way relieved, since my financial condition will be better if I go back to work in September,” she wrote in a gracious reply to Moe. “With this year of solid work behind me, I should make progress fast.” But the rejection was among the first in a series of deep disappointments that would define the last years of her life.

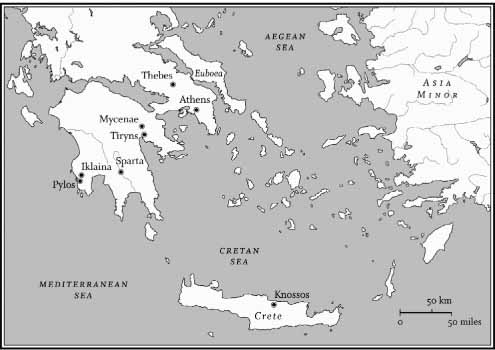

THE FIRST DISAPPOINTMENT had come four months earlier, at the end of 1946. That November, on the same day she wrote to Myres asking to see the Knossos inscriptions, Kober wrote a similar letter to an American archaeologist, Carl W. Blegen of the University of Cincinnati. Blegen was sitting on another cache of inscriptions altogether: hundreds of clay tablets, inscribed with what looked a great deal like Linear B, that he had unearthed at Pylos, on the Greek mainland, in 1939.

Blegen was even luckier than Evans had been. Where it had taken Evans a week to find his first tablet, it took Blegen less than a day. As the story went, Blegen arrived in Pylos in April 1939 and looked around for a place to dig. He chose a nearby hill and asked its owner if he could excavate there. Permission was granted on one condition: that Blegen’s workmen not disturb the ancient olive trees growing on the hillside. Blegen agreed to dig a meandering trench that would spare the trees. As a result, he liked to say afterward, Pallas Athene, the Greek goddess of wisdom, who had given man the olive tree, rewarded him.

Early the next morning, Blegen’s Greek workmen began digging the crooked trench. Almost at once, one of the men approached him, holding an object he had lifted from the earth. “Grammata,” he said, extending his hand to Blegen. It was the Greek word for writing. In the man’s hand was a clay tablet, much like those from Knossos, inscribed with similar symbols. Digging deeper, the crew began to uncover the ruins of a small Mycenaean palace. Blegen named it the Palace of Nestor, after the Homeric hero fabled to have ruled there. Inside the palace was a room filled with tablets.

The tablets had been written in about 1200 B.C.—a good two hundred years after those of Knossos—but the symbols on them looked tantalizingly like Linear B. There were about six hundred tablets, roughly a third as many as Evans had found, but each tended to contain more text. Blegen continued work at Pylos until the fall of 1939. Then, with the outbreak of World War II in Europe, he locked the tablets away in a vault in the Bank of Greece. There they remained, until long after the war.

Blegen’s discovery threatened to upend Evans’s cherished theory of Minoan supremacy: Though Evans had argued that the mainland was a rude, unlettered outpost of the high Cretan culture, here was evidence that a script—much like Linear B—had been used to record the workings of a Mycenaean palace. Worse still for Evans’s theory was the fact that the palace at Pylos had clearly been a going concern two centuries after Knossos was burned and the Minoan civilization vanquished.

Evans, by then in his late eighties, did not comment publicly on Blegen’s find, though he held fast to his ideal of Minoan domination. By his lights (and so his supporters argued), Pylos was merely a Cretan colony that had adopted the Minoan script and had the good fortune to endure beyond the destruction of Knossos. What was certain was that in the field of Aegean prehistory, Blegen’s discovery was the most important since Evans had unearthed the Knossos tablets four decades earlier. As a result, every scholar working on Linear B was itching to see the Pylos inscriptions.

Kober’s letter to Blegen was, if anything, more deferential than the one to Myres. But Blegen refused her request. “The difficulties in the way of granting it have arisen not from a dogin-the-manger attitude on our part,” he wrote in reply, “but from considerations of a practical nature. The tablets themselves are still packed away underground in Athens in a bomb-proof vault, where they remained during the war, and when they will be brought out again is wholly uncertain. … On this side we have no negatives, but only a single set of photographs which are in use all the time. We likewise have but one complete set of accurate transcriptions, also constantly needed in our own work. Under these circumstances we felt ourselves obliged to refuse similar requests in the past; and the situation has not changed today.”

Though access to the Pylos inscriptions would let Michael Ventris crack the code, Kober never got to see more than a tiny handful of them: Blegen’s demurral dragged on for years. It was a setback but not a shock. “I am a pessimist,” she wrote in 1947. “I prepare for the best, but expect the worst. Usually I am pleasantly surprised.”

She had more than enough to do in any case. There were the mountains of data from Oxford to sort and analyze, sign lists and vocabulary lists to draw up, and index cards to be cut, punched, and inked. (She had been unable to copy all two thousand inscriptions, but she did manage to copy most of them, bringing the number at her disposal to almost eighteen hundred.) She had also accepted an invitation from John Franklin Daniel to serve on the editorial board of the American Journal of Archaeology—to help him, as he wrote, vet manuscripts on Minoan sent in “by crack-pots.” (“I rather consider myself an expert on crack-pots,” she replied in acceptance, no doubt contemplating the wild, Polynesian-infused theories of some of her more ardent correspondents.)

Also at Daniel’s behest, she would soon start work on her third major paper, which would prove the most important of her career. Kober had already made two major advances: demonstrating that the language of the script was inflected, and identifying the “bridging” characters on which the writing of inflected words hinged. In her third article, she would illuminate a set of vital, long-hidden relationships among the characters of Linear B—the discovery that made Ventris’s decipherment possible.