7

THE MATRIX

IN SEPTEMBER 1947, KOBER’S FELLOWSHIP year came to an end, and before long, as she wrote ruefully to John Franklin Daniel, she was back “in academic harness” at Brooklyn College. A few months earlier, contemplating her return, she had written to Sundwall, “It must be quite wonderful when teaching is finally over and one can say to oneself that one has only to learn.” (Sundwall was by then retired.) But before the year was out, a joint effort by Sundwall and Daniel would offer her the tantalizing possibility of escape.

At the time, the Linear B tablets remained hidden in Europe, those from Knossos stored in the Heraklion Museum, those from Pylos locked away in Athens. Like many Europeans, Sundwall feared another war on the continent. In the summer of 1947, he wrote to Daniel, suggesting that a safe haven for the tablets be established somewhere in the United States. Daniel seized on the idea at once.

Young (he was in his mid-thirties), brilliant, passionate about Aegean prehistory, and possessed of what appeared to be boundless energy, Daniel seemed precisely the person to realize the plan. “Compared to you a hurricane is just a gentle breeze— except that you’re constructive,” Kober once wrote him admiringly. Philadelphia was chosen as the tablets’ prospective home: In the event of another war, it seemed less likely than New York to be attacked. Daniel set about the delicate diplomatic business of persuading the University of Pennsylvania to create an institute devoted to the study of Cretan scripts, to be known as the Center for Minoan Linguistic Research.

He next set about recruiting Kober as its head. “You are the person in this country who is working most actively in the material,” he wrote her in early September 1947. “Would you be interested and available for such a project if it were to become feasible?”

With typical pragmatic pessimism, Kober demurred at first. “I have a job which, while far from ideal in many ways … does pay well,” she replied. “I don’t intend to keep it all my life, but at present the kind of work I’d really like”—pure research—“is open only to men.”

In the coming weeks, Daniel wore her down. “Dangling … the Institute in front of my nose like that, when all I’m teaching this term is Greek and Roman literature in Translation, and high-school level Vergil, is almost more than I can bear,” she wrote him in late September. “I daren’t say no, and I daren’t say yes.”

For Kober, finances were a major concern. At Brooklyn, she wrote, she was paid “a big salary for a woman teacher,” more than $6,000 a year—roughly $62,000 today. “I know enough about academic salaries for women to realize that financially I can’t do better, at least for another ten years,” she told Daniel. “All the same, if it weren’t that I have Mother to consider, that wouldn’t make any difference.”

But over the next few months, as Daniel continued his backstage machinations, the job began to tug at her increasingly. By chance Roland Kent, a well-known professor of Indo-European linguistics, had just retired from Penn, and Daniel hit upon his departure as a way of bringing Kober to the university, with her duties divided between running the Minoan institute and teaching classes on subjects like Greek phonology, a topic much dearer to her heart than high-school-level Vergil.

“Don’t count on it too much, because I am still pretty young in university politics and it may well be that my word will carry even less weight than I timidly think,” Daniel cautioned her by mail that fall. “Furthermore I am afraid that there is something of a prejudice against giving faculty appointments to women. How strong it is I don’t know, but will soon find out.”

After several months, Daniel was able to report that his efforts at Penn were going slowly but well. If he could arrange it, he wrote Kober in December, he would make a course on Cretan scripts part of her portfolio there. With that, she was hooked. “Your latest letter … has me sitting here with my tongue hanging out, and that’s bad,” she replied. She continued:

I’m trying to preserve my equilibrium so that I’ll be happy no matter how things turn out. You’re heartless. … Now you add a course in Minoan scripts!!! I’ve been looking at the list of courses, and feel much encouraged. I could begin teaching most of them to-morrow, and plan the entire course in a week or two. … The salary doesn’t concern me too much. … The most important consideration is that I’ll love the work. … If you can do half as well in selling me to Pennsylvania as you have done in selling Pennsylvania to me—it’s in the bag.

As Kober and Daniel both knew, the gears of university administration grind with the speed of geologic time, and there would be no word on the job right away. In the meantime, though, he had conceived something equally important to occupy her.

It is hard to imagine now, but among their other effects, the shortages of the postwar years made the dissemination of ideas among scholars a real challenge: The process depended crucially on printing, which remained an uncertain proposition, and paper, which remained a scarce commodity. In the late 1940s many Europeans still had scant access to American academic journals, and vice versa. In the autumn of 1945, Kober lamented that the Brooklyn College library’s most recent copy of Archiv Orientálni, an important Czech journal, was from 1938, “as might be expected.” In 1946, she had to enlist the aid of the Czech Consulate to obtain a copy of Hrozný’s “decipherment” of Linear B.

The number of people working seriously on the Cretan scripts was so tiny, their mutual contact so limited, and their collective knowledge so atomized, that most were effectively laboring in isolation. Beyond this small group was a larger one of “non-Minoan” archaeologists and classicists, who knew far less about the scripts than they might. What was needed, Daniel realized, was one overarching article, disseminated as widely as possible, that laid out precisely the current state of knowledge about the scripts. He knew just the person for the job, and in early September 1947, he wrote to her, soliciting the piece for the American Journal of Archaeology:

Everybody is interested in the Minoan script and it is astounding how few people know anything about it. … I think it would be useful not only to summarize the most recent work in the matter but to state the problem generally, indicate the various lines which have been followed in attempting to crack the script and saying a brief word about the real merits of the different methods; then, I think, a brief statement, in which I hope you will not be modest, of the present state of the study, with your ideas as to its probable future development… [and a summary of] the fallacious attempts to decipher it.

Though Daniel and Kober’s friendship was conducted almost entirely by mail (they met only a few times, usually at scholarly meetings), there existed between them an intellectual sympathy so deep it bordered on telepathy: As it happened, she was just then thinking of writing a state-of-the-field article herself. “One of the remarkable things about you is that you always anticipate what I’m going to say,” she wrote by return mail. “I think your suggestion about an article on what is known about Minoan just suits the situation. It will also make the Guggenheim Foundation happy, since it will be a sort of summary of my year’s work.”

By late September, she had embarked on the torturous process of drafting the paper. “About the article—I hope it comes up to expectations, but I’m beginning to have my doubts,” she wrote to Daniel. “My typewriter seems to have taken the bit into its mouth (how’s that for a mixed metaphor). At any rate, what has come out isn’t at all what I expected.” By early October, she was hard at work on the fourth draft; by the middle of the month, as she wrote to Daniel, she had completed “the sixth draft (durn it!).” Throughout the article, she was careful not to cite any inscriptions from the still-unpublished Knossos tablets, honoring her promise to Myres.

In late October, Kober sent Daniel the finished manuscript. “This is the best I can do,” she wrote. “I should have rewritten one or two pages, but I’m afraid to touch the typescript, for fear that I will feel like writing another draft. I’m sick and tired of it, truth to tell. I’ve worked harder on this than on anything I’ve ever written, and doubt that it’s worth beans. If you don’t think it’s worth printing—well, I agree.” In fact, the paper would be the most important of her career, and the one that furnished the most significant step forward in the decipherment thus far.

IN MID-DECEMBER 1947, before her article appeared, Kober made what she called a “slight discovery.” Sifting her cards, she had managed to pinpoint the special function of the character  , colloquially known to investigators as “button.” Though the discovery was small, the noteworthy thing about it is that it was she, and not Michael Ventris, who made it: Until now, historians have attributed it to Ventris, who reached the same conclusion independently more than three years later, in January 1951.

, colloquially known to investigators as “button.” Though the discovery was small, the noteworthy thing about it is that it was she, and not Michael Ventris, who made it: Until now, historians have attributed it to Ventris, who reached the same conclusion independently more than three years later, in January 1951.

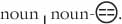

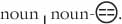

What first Kober and then Ventris noticed was that  kept cropping up in a very particular spot: at the ends of words. As Kober knew from perusing the tablets’ inventories, many of those words were nouns. In addition, each “buttoned” noun typically followed another noun, resulting in this characteristic sequence:

kept cropping up in a very particular spot: at the ends of words. As Kober knew from perusing the tablets’ inventories, many of those words were nouns. In addition, each “buttoned” noun typically followed another noun, resulting in this characteristic sequence:

Though she still had no idea how  was pronounced, Kober realized that in the language of the tablets, it must be the conjunction “and.” The symbol was functioning as a kind of suffix: Tacked on to the end of one noun, it linked that noun to the one before it.

was pronounced, Kober realized that in the language of the tablets, it must be the conjunction “and.” The symbol was functioning as a kind of suffix: Tacked on to the end of one noun, it linked that noun to the one before it.

As Kober knew, “and” can function as a suffix (or prefix) in other languages. In Latin, “and” (-que) can be tacked on to the end of a noun, linking it to the previous one. (A well-known example is the phrase Senatus Populusque Romanus—“the senate and the people of Rome”—abbreviated SPQR and ubiquitous on Roman coins, documents, and the like.) In Hebrew, “and” (v-) attaches to the beginning of a noun, linking it to the noun before: tohu vabohu, “without form and void,” from the book of Genesis.

Kober concluded—correctly—that  worked similarly in the Minoan language. But she was never able to make her finding public, and as a result never got credit for it. This was partly an accident of timing: She made the discovery on December 14, 1947, too late to prepare a paper on the subject for the year-end annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, as she would have liked. “Too bad I didn’t discover it a couple of weeks ago,” she wrote Daniel regretfully.

worked similarly in the Minoan language. But she was never able to make her finding public, and as a result never got credit for it. This was partly an accident of timing: She made the discovery on December 14, 1947, too late to prepare a paper on the subject for the year-end annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, as she would have liked. “Too bad I didn’t discover it a couple of weeks ago,” she wrote Daniel regretfully.

She may not have had time in any case. By the late 1940s she had become enmeshed in a gargantuan, long-distance effort to proofread, fact-check, and type Myres’s work on Scripta Minoa II. Though to Kober, as Professor Thomas Palaima points out, the job had the quality of a sacred duty—one that might let her ensure the absolute accuracy of the material Myres had inherited from Evans—it was proving to be a frustrating, unrewarding, and labor-intensive enterprise that at bottom was little more than secretarial work. And she was carrying a full load at Brooklyn College all the while.

Even had Kober been able to make her findings on  public, it is quite possible that Ventris would not have learned of them anyway. Her narrative and his don’t truly begin to converge until the spring of 1948, when he started corresponding with Linear B investigators around the globe. From the letters between them, which begin that March, it is plain that Kober’s work remained unavailable in Britain. In a letter to her in May 1948, Ventris acknowledges receiving copies of her articles— “I’m extremely glad to have them,” he wrote—in a manner that strongly suggests he had not seen them before.

public, it is quite possible that Ventris would not have learned of them anyway. Her narrative and his don’t truly begin to converge until the spring of 1948, when he started corresponding with Linear B investigators around the globe. From the letters between them, which begin that March, it is plain that Kober’s work remained unavailable in Britain. In a letter to her in May 1948, Ventris acknowledges receiving copies of her articles— “I’m extremely glad to have them,” he wrote—in a manner that strongly suggests he had not seen them before.

Kober and Ventris would meet only once, briefly, in England, in the summer of 1948, and there is no direct record of what either thought of the other. But it is clear from the absence of the kind of warm, respectful correspondence that Kober maintained with colleagues like Daniel and Sundwall that she did not hold Ventris in especially high esteem.

She had no use for amateurs, many of whom persisted in writing her with their latest theories on the Cretan scripts. One of her most chronic correspondents—whose letters are charming to read today, but to Kober were undoubtedly a source of immense irritation—was William T. M. Forbes, a Cornell University entomologist and dabbler in ancient scripts. (It was he who thought the Minoan language was a form of Polynesian.) His letters to Kober, written over a period of years, contain page upon page of unsupported linguistic speculation before closing with cheery sign-offs like “But now back to the Lepidoptera for a time.” Though Kober’s replies have not been preserved, it is evident from Forbes’s letters that she took the time to write him back, at pedagogical length, which left him grateful if unpersuaded. Her handwritten notes in the margins of his letters to her (“No!” “Right!!”) attest to their claim on her time.

To Kober, Ventris appeared to be yet another hobbyist awash in wild, unfounded enthusiasms. Neither linguist nor archaeologist, he was an architect who worked on the tablets in his spare time. Their correspondence had an inauspicious beginning: His first known letter to her, on March 26, 1948, contains a slew of things that must surely have set her teeth on edge. “I should be very interested to hear how far you have got at present, and particularly if you have any ideas on phonetic values,” Ventris wrote. He restated his conviction that the Minoan language was a form of Etruscan, a belief he had first made public in a 1940 article in the American Journal of Archaeology, published when he was a teenager. Neither his talk of sound-values nor his identification of a specific language as Minoan would have sat well with Kober, who remained resolutely agnostic on both subjects to the end of her life.

“Minoan is only a part-time job with me,” Ventris wrote in the same letter, “and there is always the problem of getting enough material to work on. In fact, I don’t feel like coming out publicly with any more theories until I’ve laid my hands on all the available material.” He went on to describe setting up a network of Linear B characters that had consonants or vowels in common—relationships Kober had already described in her influential paper of 1946, “Inflection in Linear Class B.” He also talked of setting up a “grid” by which those shared consonants and vowels could be plotted, which was precisely what Kober had done by then in the state-of-the-field paper Daniel had commissioned.

Later in the spring of 1948, on the verge of quitting his day job to immerse himself completely in Linear B, Ventris wrote her, “At the moment I’m engaged in a rather tricky architectural competition, but after that I think I shall have to devote the rest of the year whole time to Minoan, because it isn’t really worth doing in fits and starts,” a line that to Kober must have fairly screamed “rich dilettante.”

It wasn’t that Kober saw the decipherment as a competition. “Rivalry has no place in true scholarship,” she later wrote to Emmett L. Bennett Jr., a young classicist at Yale. “We are co-workers. I will be glad to help you in any way possible. The important thing is the solution of the problem, not who solves it.” Nor would she have felt threatened by amateurs like Ventris in any case. It was that she could abide neither their unfounded guesswork nor their persistent correspondence, which, through a combination of good manners and fealty to the subject at hand, she spent too much of her scarce free time answering.

BY THE END of 1947, Daniel, continuing his campaign to bring Kober to Penn, had reason to feel encouraged. “Please send me FAST a complete list of your publications, including book reviews, classes you have taught, and the titles of lectures you have given,” he wrote her in early December. “I have just come from a meeting of the committee to appoint a successor to Kent, and … there was some very strong support for your nomination. … What this all adds up to is that I think there is an excellent chance.”

At Daniel’s request, Kober solicited letters of recommendation from some of the eminent scholars who had taught her over the years. One, Franklin Edgerton, whose Sanskrit classes she attended at Yale, was happy to comply, if amazed. As he wrote her:

I am indeed astonished by the news conveyed in your letter. … The astonishment is not uncomplimentary to you; it is chiefly on account of the fact that I had no idea that the University of Pennsylvania ever had appointed or would appoint a woman to a major position. If they actually do offer you a full professorship at a good salary … it seems to me that I would take it, if I were you.

By this time, Kober needed no persuading. “Everybody tells me this job, if it materializes, would be a wonderful opportunity,” she wrote to Daniel. “I know that too.” She continued:

It’s too good to be true. I write letters and … talk about it, but I don’t believe it. All the same, I’ve been figuring out what I would do if the job actually materializes. I think I would work it this way: I’d take it, and try to get a year’s leave without pay from Brooklyn College. In that way, I can find out how it really works out, and if I’m not as good as I think I am, can retire gracefully at the end of the year, to everybody’s relief, and come back here. If it works out, I can resign here. …

I’ll have to figure on doing very little with Minoan that first year—but getting [the research center] into order and plugging away at new courses will be a very valuable experience, and Minoan is at the stage where any new information may be the clue. …

She closed the letter: “I’ve never told you I’m grateful for all you’re doing. I am. It’s been fun, too.”

Amid all this, Kober was attempting to arrange two overseas trips. The first was a return to England: Sir John Myres wanted her to help lobby the Clarendon Press, an imprint of Oxford University Press, to speed the publication of Scripta Minoa II, which had ground to a halt amid postwar retrenchments. In the spring of 1948, she finally secured passage—no small trick, given the austerities still affecting ocean travel then. “First Class. Ouch!” Kober wrote Daniel in late April. “But that was the only way I could go.” She would sail from New York on the RMS Mauretania on July 21 and reach Oxford by the end of the month. She would sail home from Liverpool on September 10, arriving in Brooklyn just before school began.

The second trip was to Crete, where Myres wanted her to go to check Evans’s transcriptions against the tablets in the Herak-lion Museum, provided they were accessible by the time she got there. But even if they were, she had neither the time nor the money to make the journey: Brooklyn College would grant her only six months’ unpaid leave. “Six months is ample time for me to starve to death, since I’ve spent all my money last year,” she had written to Daniel in late 1947. She added—and it is wrenching to read in retrospect—“Six months mean very little to me, but of course, they mean a lot to Myres.” (Myres would outlive her by four years.)

“My only solution,” Kober wrote, “would be to stop all scholarly work for six months, write a detective story and hope it would be a best-seller.” Of course, her body of work, read in sequence, was a detective story, and a great one, though it would take Michael Ventris building on the foundation she erected to solve the mystery. In the end, Kober’s worries about the Cretan trip were moot. The Knossos tablets remained in hiding for years, and she would never get to see them.

IN EARLY 1948, Kober’s state-of-the-field article appeared in the American Journal of Archaeology under the crisp title “The Minoan Scripts: Fact and Theory.” Erudite, authoritative, and coolly polemical, it began:

The basic distinction between fact and theory is clear enough. A fact is a reality, an actuality, something that exists; a theory states that something might be, or could be, or should be. … In dealing with the past we are concerned, not with something that exists, but with something that has existed. Our facts are limited to those things [from] the past which still exist; everything else is theory, which may range all the way from practical certainty to utter impossibility, depending on its relationship to known facts.

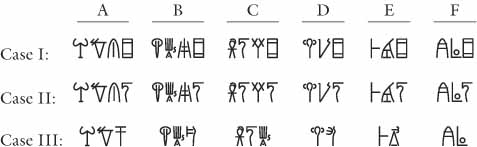

The heart of the paper picked up where her 1946 article had left off, with the critical third character—the “bridging” character—in Linear B words. From that character, Kober had long known, sprang a network of relationships among the sounds of the Cretan language. Now, in this paper, she began to plot those relationships by means of a grid.

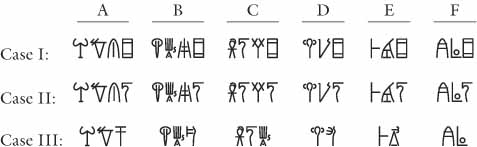

As before, Kober paid particular attention to what happens when an inflected language bumps up against a syllabic script. By this time she had discovered additional words that seemed to fit the pattern of inflection she had previously described. In the new paper, her expanded paradigm contains six words (she believed they were all nouns) in each of three cases—six sets of “triplets,” as Ventris would call them. As it happened, the three words in Column B ( ,

,  , and

, and  ) would play a critical role in the decipherment.

) would play a critical role in the decipherment.

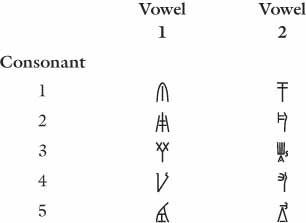

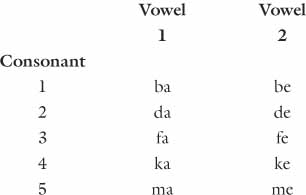

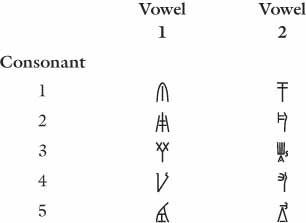

Once again, Kober homed in on the third sign of each word (or, for shorter words, like those in Columns D and E, the second sign). This was the “bridging” character, whose function she had illustrated so elegantly in her previous article. It is this character that is at the heart of the matrix, or grid, that she unveiled in the new paper. The grid is modest—just five signs by two signs—but it presents, for the first time anywhere, some relative sound-values for characters in the script. Kober did not invent the concept of the grid, nor did she claim to: Its use in archaeological decipherment dates to the seventeenth century. But her great innovation, as Maurice Pope writes in The Story of Archaeological Decipherment, “was the idea of constructing such a grid in the abstract… without settling what particular consonant or vowel it might be that a particular set of signs had in common.”

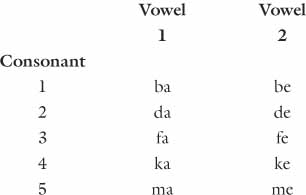

Captioned “Beginning of a Tentative Phonetic Pattern,” Kober’s grid looked like this:

Each symbol in the grid is one of Kober’s “bridging” characters, and each character’s position marks, so to speak, its phonetic coordinates. Reading across Row 1, for instance, we see that  and

and  start with the same consonant but end in different vowels—whatever those consonants and vowels might be. Reading down Column 1 tells us that

start with the same consonant but end in different vowels—whatever those consonants and vowels might be. Reading down Column 1 tells us that  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  start with different consonants but end in the same vowel. Though the specific sound-values remained unknown, Kober’s grid made it possible to show the relative relationships among these ten characters. A comparable grid for English—and here the sound-values have been assigned arbitrarily—might look like this:

start with different consonants but end in the same vowel. Though the specific sound-values remained unknown, Kober’s grid made it possible to show the relative relationships among these ten characters. A comparable grid for English—and here the sound-values have been assigned arbitrarily—might look like this:

Kober’s grid illustrates the web of contingencies that emerges when an analyst plots the changes in the “bridging” character across different cases of the same word. To modern eyes, her grid has the quality of a Sudoku puzzle, in which the interdependencies among its cells (“If I’ve already used a 5 in this square, I can’t use a 5 in an adjacent square”) help the investigator arrive at the only logically possible solution. For, as she clearly knew, once the sound-values of just a few Linear B characters were discovered, the entire grid, in explosive chain reaction, would start to fill itself in.

What Kober showed is that when an inflected language is written with a syllabic script, mapping the inflection pattern is a way to “force out” hidden information about the relationships among the signs. It was this information, so masterfully presented in her new article of 1948, that furnished the first viable key to the mapping between sound and symbol in the lost Cretan language.

Near the close of the article, she wrote:

People often say, in connection with the Minoan scripts, that an unknown language written in an unknown script cannot be deciphered. They are putting the situation optimistically. We are dealing with three unknowns: language, script and meaning. A bilingual inscription is useful because it gives meaning to an otherwise meaningless combination of symbols. Those who deplore the fact that no Minoan bilingual has been found, forget that a bilingual is no guarantee of immediate decipherment. The Rosetta Stone was found in 1799. Champollion began his intensive work in 1814, but it was not till 1824, a quarter of a century after the Rosetta Stone was discovered, that he was able to publish convincing proof that he had found the clue to the decipherment of Egyptian.

“Let us face the facts,” she wrote in conclusion:

An unknown language, written in an unknown script cannot be deciphered, bilingual or no bilingual. It is our task to find out what the language was, or what the phonetic values of the signs were, and so remove one of the unknowns. Forty years of attempts to decipher Minoan by guessing at one or the other, or both, have proved that such a procedure is useless. … The people of ancient Crete did not live in a vacuum, nor did they disappear suddenly and completely. They left traces of their languages behind. These traces are no good to us now, because we do not know enough about their scripts to use them intelligently.

The task before us is to analyze these scripts thoroughly, honestly, and without prejudice. …

When we have the facts, certain conclusions will be almost inevitable. Until we have them, no conclusions are possible.

IN LATE DECEMBER of 1947, Kober had received a special-delivery letter from Daniel warning of a “slight setback” regarding the job at Penn. “You are no. 2 on nearly everyone’s list,” he wrote:

Your Minoan accomplishments… have already been made clear to the Board. … What is needed and needed badly is a strong endorsement of your ability to handle Indo-European and particularly Greek and Latin linguistics. Several people have written to say that they have no doubt that you could give satisfactory teaching in this field, but several have intimated that you might have to bone up on it. What is needed is a categorical statement to the effect that you are fully qualified in these fields. There is no doubt whatever in my mind that you are, but it is going to take more than my statement to swing this matter. If you can get one such statement from a first-rater, I think that your chances of landing the job will be very good indeed.

In reply, Kober asked him point-blank: “Don’t you think a lot of the opposition is really based on the fact that I’m a woman? Even if it isn’t specifically mentioned.” She went on: “As for the ‘boning up’—anybody must ‘bone up’ for a graduate course, or for a course one has never taught. All my great teachers … do their homework, even for courses they’ve taught over and over again. Of course I’ll have to work at preparation.”

Daniel answered, “The fact that you are a woman has absolutely nothing to do with the case.” The trouble, he wrote, lay with several members of the search committee, Indo-European scholars at the university. One was “weak, lazy, and impressionable”; the other “has the first two qualities, but has a stubbornness which [the first man] seems to lack.” A third “has been an assistant professor for seven years, and … told me perfectly frankly that he felt that he had to oppose any appointment at a higher rank than that, because it would shut him out forever. Isn’t that nice?”

Of the committee members as a group, Daniel wrote, “I am not being unduly bitter when I say that their controlling criterion seems to be mediocrity. They are third raters themselves … and simply do not want to get people here who will show them up. … While he has not said so in so many words, I am sure that Crosby, who is chairman of the department, has made up his mind that he will block you if he possibly can. … I certainly have learned a lot about human nature, the genus professoricus [sic], in this matter!” The university’s intransigence continued through the start of 1948, and in February Daniel wrote her, “I am limiting my activities to trying to undermine your rivals.”

Finally, in May 1948, Penn made up its mind. “I have bad news,” Daniel wrote. The university had appointed the eminent Indo-European linguist Henry Hoenigswald to the post. “I am terribly disappointed about it, perhaps more so than you will be,” Daniel continued. “I was dreaming wonderful dreams of the terrific set-up we would have here with you and the Minoan collection. … Hoenigswald is a good man, but it won’t be quite the same. It may give you some satisfaction to know that you were very close to getting it; if one person had swung from opposition … to support, I think that we could have swung it. But that is spilled milk.”

“Well, it was fun while it lasted,” Kober replied. “I can’t say your news was unexpected, because I am a pessimist from ’way back.”

There was one silver lining: Penn wanted to go ahead with the Minoan center anyway, with Kober spending one weekend a month in Philadelphia to tend to it. In anticipation, she was named a research associate at the university museum, an honorary title with no stipend.

By mail, she and Daniel began to draw up their plans. Kober compiled a list of people she would invite to be associates of the center—forming a “mutual aid society,” as she called it, to share the fruits of their research. “If it works as we hope,” she wrote to Henry Allen Moe in July, “scholars of a dozen different countries, now working more or less in isolation, will be able to cooperate, and perhaps our united efforts will solve the problem.” At the top of the guest list she put Sundwall and Myres, followed by a few other scholars. Next-to-last she put Bedřich Hrozný, the object of her frequent scorn, whose name she followed with three question marks. In last place was Michael Ventris, followed by four question marks.

BY THIS TIME, Ventris, too, had been enlisted by Myres to help prepare the Knossos inscriptions for publication. The two men had begun corresponding in 1942, when Myres wrote to Ventris to compliment him on his 1940 article in the American Journal of Archaeology. At war’s end, he wrote to Ventris again, with an offer similar to the one he would make to Kober: permission to see Evans’s unpublished transcriptions.

Ventris accepted eagerly, though he would not be able to take up the offer until 1946. Soon afterward, at Myres’s behest, he was carefully hand-copying hundreds of inscriptions from Evans’s notes and photographs so that they could be reproduced clearly, as Kober was also doing. (With a good two thousand inscriptions, there was ample copying work for them both.) Ventris began spending each night at an elegant table in his London home, drawing Linear B symbols in his impeccable architectural hand.

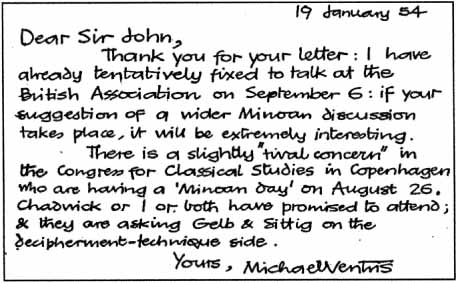

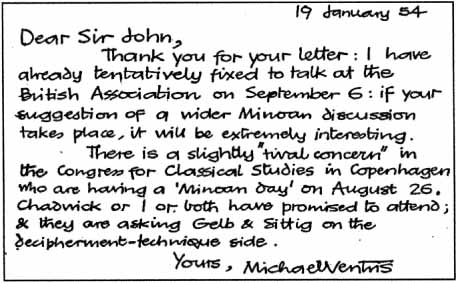

Where Kober’s Linear B transcriptions are serviceable, Ventris’s are the work of an artist. Even his everyday handwriting, the letters crisply squared off and perfectly proportioned, the lines absolutely horizontal, is so remarkable-looking that it resembles the penmanship of a skilled blind person writing with the aid of a straight-edge.

Ventris’s everyday handwriting, remarkable in appearance.

“Mr. Ventris would have no trouble getting a job as scribe for King Minos,” Kober wrote after seeing a batch of his copying, a remark that appears at once complimentary and belittling. Ventris might be a superb draftsman, she seemed to be saying, but he was no more than that. What is clear, with hindsight, of both Kober and Ventris is that each underestimated the other deeply.

IN MIDSUMMER 1948, plans for the Minoan center were put on hold temporarily, until both Kober and Daniel returned from overseas trips—hers to Oxford and his a long voyage through Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey. Daniel’s trip, to scout sites for future excavations by the university museum, would keep him abroad from September 1948 through February 1949; he was due to set sail for Athens on September 10, the day Kober sailed home from England to New York.

On July 21, 1948, Kober embarked for England once more. She would not only need to rouse the Clarendon Press to action but, should they decide to go ahead, she would also have to continue helping Myres prepare the complex, unwieldy manuscript for submission. So much depended on its being published. “Until it is,” she wrote, “it will be impossible to make progress.”

In Oxford, Kober found Myres even frailer than before, and the state of his health made access difficult. “Lady Myres keeps him in bed Mondays and Wednesdays,” she wrote to Daniel from Oxford in August. She was just then in the midst of revising Myres’s vocabulary list, which, she wrote, “is in perfect chaos. … Every other word requires correction.” Perhaps that was not surprising—Myres was an archaeologist and not a linguist—but the state of his data did Kober no favors.

For the first time since her association with him began, Kober expressed reservations about the quality of Myres’s work. “I only hope he accepts my corrections,” she wrote to Daniel. “I’d hate to have him publish what he has and mention me in connection with it. He is far from well, which makes it difficult to press a point.”

Kober understood that Myres was living only for the volume’s publication. But her correspondence from this trip makes clear that dealing with him was a struggle from the moment she arrived. “I’ve had enough trouble getting him to correct the Linear B,” she wrote in another letter to Daniel that August. “I’ve just about rewritten Scripta Minoa II and have the Clarendon Press ready to print. Now I’ll have to get Sir John to give up the manuscript to be printed. Better burn this letter.” She signed off: “Just now I’m writing out the vocabulary for the Press—a month’s work, and less than a week to do it. What a life!”

It is here, in Oxford, that Kober’s and Ventris’s stories dovetail for the first brief, painful time. Ventris had also been summoned to Oxford in the summer of 1948 to help prepare Scripta Minoa II for publication, and he arrived during Kober’s visit. But, apparently cowed by the combined scholarly firepower of Kober and Myres, he quickly fled the scene, a pattern of abdication he would repeat throughout his life.

Besides correcting Myres’s Linear B vocabulary lists for publication, Kober had a spate of purely scribal duties, including the tedious hand-copying of hundreds of inscriptions for the printer. She also agreed, in retrospect unwisely, to help Myres prepare the manuscript of yet another volume, Scripta Minoa III, which would be devoted to Linear A.

There were a few consolations. Foremost was Kober’s hope that Scripta Minoa II would finally see publication, freeing her to use the inscriptions in her own work. There was the joy of staying again at St. Hugh’s College, whose intellectual climate she had pined for in the year since she’d been there. There was also the letter that Daniel mailed to her in Oxford, written days before he sailed for Greece. “Two deans … still wish there were some way of getting you a full time appointment at Penn,” he wrote. “Who knows: it may work out yet.”

Despite her efforts, Scripta Minoa II was no closer to publication when Kober sailed for New York in September. Apart from the deplorable state of the manuscript itself was the fact that she and Myres disagreed on a fundamental organizing principle: how to classify and present the nearly two thousand Knossos inscriptions. He wanted to present them much as Evans had, organized by the location in the palace in which they were found. In her own work, by contrast, Kober had spent years grouping the inscriptions together by subject: all the tablets about grain discussed together; the ones about wine; about men, horses, and so forth. To her, this was the more meaningful classification, as it spoke to the tablets’ focus on lists, which in turn let her pluck out the nouns and their various inflected forms.

Myres came around to her way of doing things, but a huge sticking point remained: He didn’t think the language of Linear B was inflected. “He wants to use my classification of the inscriptions but still insists there are no cases!” Kober had written Daniel in frustration from Oxford. “My classification depends on case.”

From this point on, the tone of her correspondence about Myres, once worshipful (“I am really very much in awe of that great historian, J.L. Myres,” she had written to Myres himself in 1946), starts to change. In a letter to Sundwall written shortly after her second trip, Kober said that Myres “still thinks … that there are no cases, also, that anything he doesn’t understand is due to the fault of the Minoan scribe.” To Emmett Bennett of Yale, she wrote: “Somewhat against my better judgement, I permitted Sir John Myres to use my classification as a basis for his discussion of the Linear B inscriptions. I didn’t like the idea because I would prefer to explain my classification myself, since he still thinks all words are nouns, and all in the nominative case. But I finally said he could do so, provided he stated his interpretation was his own, and not mine. … I now plan to publish the classification with my own interpretation as soon as SM is out.”

ON SEPTEMBER 18, 1948, Kober arrived in Brooklyn to the start of a new term. Soon she was swamped. “I’ve been home almost a month now, and haven’t done as much as I could do in a couple of days of uninterrupted work,” she wrote Myres in October. “It is annoying to have to stop what I’m doing at 11 at night, often right in the middle of something, get ready for bed so that I can get up for school in time, then find that committee meetings, and unexpected visitors, keep me from continuing for a couple of days.”

She had not only her school duties to occupy her time but also Myres’s typescript of Scripta Minoa II to correct for the printer, as well as his handwritten manuscript of Scripta Minoa III to begin typing. All this left her barely an hour a day for her own work on Linear B. She could look ahead with pleasure, at least, to Daniel’s return from overseas in five months, when they could discuss plans for the Minoan center and even, just possibly, a faculty appointment at Penn. “Wishing you the best of luck and looking forward to seeing you again in February,” he had written her in early September, before he set sail.

On December 18, 1948, in Ankara, Turkey, John Franklin Daniel died of a heart attack at the age of thirty-eight.

, colloquially known to investigators as “button.” Though the discovery was small, the noteworthy thing about it is that it was she, and not Michael Ventris, who made it: Until now, historians have attributed it to Ventris, who reached the same conclusion independently more than three years later, in January 1951.

, colloquially known to investigators as “button.” Though the discovery was small, the noteworthy thing about it is that it was she, and not Michael Ventris, who made it: Until now, historians have attributed it to Ventris, who reached the same conclusion independently more than three years later, in January 1951. kept cropping up in a very particular spot: at the ends of words. As Kober knew from perusing the tablets’ inventories, many of those words were nouns. In addition, each “buttoned” noun typically followed another noun, resulting in this characteristic sequence:

kept cropping up in a very particular spot: at the ends of words. As Kober knew from perusing the tablets’ inventories, many of those words were nouns. In addition, each “buttoned” noun typically followed another noun, resulting in this characteristic sequence:

was pronounced, Kober realized that in the language of the tablets, it must be the conjunction “and.” The symbol was functioning as a kind of suffix: Tacked on to the end of one noun, it linked that noun to the one before it.

was pronounced, Kober realized that in the language of the tablets, it must be the conjunction “and.” The symbol was functioning as a kind of suffix: Tacked on to the end of one noun, it linked that noun to the one before it. worked similarly in the Minoan language. But she was never able to make her finding public, and as a result never got credit for it. This was partly an accident of timing:

worked similarly in the Minoan language. But she was never able to make her finding public, and as a result never got credit for it. This was partly an accident of timing:  public, it is quite possible that Ventris would not have learned of them anyway. Her narrative and his don’t truly begin to converge until the spring of 1948, when he started corresponding with Linear B investigators around the globe. From the letters between them,

public, it is quite possible that Ventris would not have learned of them anyway. Her narrative and his don’t truly begin to converge until the spring of 1948, when he started corresponding with Linear B investigators around the globe. From the letters between them,  ,

,  , and

, and  ) would play a critical role in the decipherment.

) would play a critical role in the decipherment.

and

and  start with the same consonant but end in different vowels—whatever those consonants and vowels might be. Reading down Column 1 tells us that

start with the same consonant but end in different vowels—whatever those consonants and vowels might be. Reading down Column 1 tells us that  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  start with different consonants but end in the same vowel. Though the specific sound-values remained unknown, Kober’s grid made it possible to show the relative relationships among these ten characters. A comparable grid for English—and here the sound-values have been assigned arbitrarily—might look like this:

start with different consonants but end in the same vowel. Though the specific sound-values remained unknown, Kober’s grid made it possible to show the relative relationships among these ten characters. A comparable grid for English—and here the sound-values have been assigned arbitrarily—might look like this: