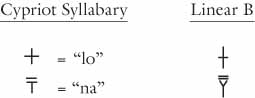

The Cypriot syllabary.

IN THE SPRING OF 1952, Scripta Minoa II was published at last. (Though Myres had written Kober in 1948 that “all your help in the B volume will of course be acknowledged in the preface to it, very gratefully,” the published book gave scant indication of the full extent of her years of hard labor.) The volume, with its hundreds of inscriptions, gave Ventris still more data. In May, he tried his place-name experiment a second time, with one significant difference: He allowed himself to make use of a clue he had previously shunned—the only external clue in existence to the possible identities of some Linear B characters.

The clue had been available to investigators from the very beginning, but as they all knew, it was a risky one. It came in the form of an Iron Age writing system known as the Cypriot script. Also a syllabary, the script was used to record the indigenous language of Cyprus between about the seventh and the second centuries B.C. (The Cypriot syllabary was a descendant of the Cypro-Minoan, on which John Franklin Daniel had done important research in the early 1940s.) The language of the Cypriot script remained a mystery, but the sound-value of each character was known: After the Hellenization of Cyprus, the syllabary was retained for a time to write Greek, and the island teemed with Greek syllabic inscriptions on monuments and coins. Thanks to the discovery in 1869 of a bilingual inscription in Cypriot and Phoenician, the Cypriot syllabary was deciphered in the 1870s.

The Cypriot syllabary.

A handful of Cyriot characters looked like Linear B signs, a resemblance first pointed out in 1927 by the scholar A. E. Cowley:

The Cypriot syllabary was a millennium younger than Linear B, and, as investigators knew, a lot can happen to a script in a thousand years. Similar-looking scripts often record extremely dissimilar languages: English, Hungarian, and Vietnamese, for instance, are all written in versions of the Roman alphabet. Even in related languages, identical characters can have entirely different sound-values. In German, a close relative of English, the letter w is pronounced “v,” while the letter v is pronounced “f.” One has only to compare the American and German pronunciations of the word Volkswagen to take the point.

However tenuous the connection, the Cypriot script offered the only external clue the Linear B decipherers had to work with, and none could resist exploring it. In the early 1940s, Kober had tried plugging Cypriot sound-values into the Knossos inscriptions but, as she later wrote, “had no results.” Evans, too, had tried to exploit the clue. On one fragmentary tablet in particular, it seemed to rear up seductively:

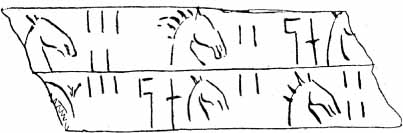

The fragment belonged to a tablet inventorying the horses of Knossos, and it appeared to count horses of two kinds: those with manes (shown at top center and bottom right), which were evidently full-grown horses, and those without (top left, top right, bottom center), evidently young horses. On the intact portion of the tablet, each maneless horse is preceded by a two-character Linear B word:  .

.

Evans tried substituting Cypriot values for those characters. What he got was “po-lo,” which looked an awful lot like pōlos, the Classical Greek word for “foal.” (The English word foal is a cognate, as is the name of the sport polo.) But championing Minoan supremacy to the last, he rejected the reading as mere coincidence—though one certain to be seized upon, as he wrote in a testy footnote in The Palace of Minos, by “those who believe that the Minoan Cretans were a Greek-speaking people.”

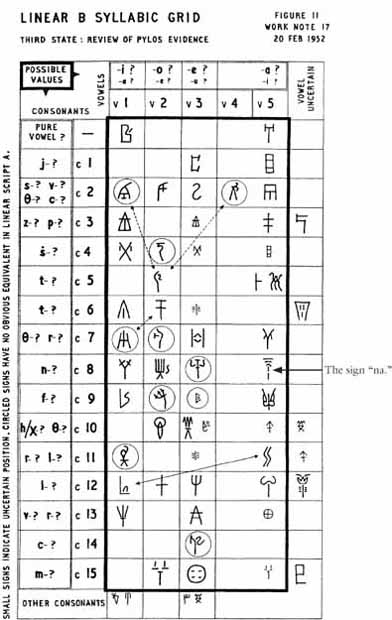

Ventris, who also believed that Linear B recorded a non-Greek language, had remained suitably wary of this Cypriot clue. But in May 1952, after revisiting his earlier idea about Cretan place-names, he allowed himself to follow it. As an experiment, he plugged certain Cypriot sound-values into his third grid, shown on the next page.

He started by unpacking  , which he had previously rejected as “Amnisos,” the Classical Greek name of the port of Knossos. From his analysis of the “pure vowel” signs, he was reasonably certain that

, which he had previously rejected as “Amnisos,” the Classical Greek name of the port of Knossos. From his analysis of the “pure vowel” signs, he was reasonably certain that  stood for “a.” He next turned to the Cypriot sign

stood for “a.” He next turned to the Cypriot sign  , “na.” If the Linear B sign

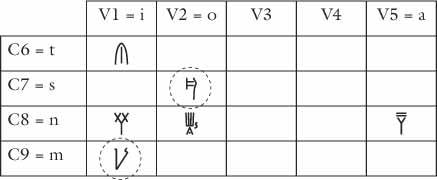

, “na.” If the Linear B sign  had the same value, then he could insert “na” into the grid where Row C8 and Column V5 intersected—in the cell whose “phonetic coordinates” were the consonant “n” and the vowel “a.” (On his grid, Ventris draws the character as

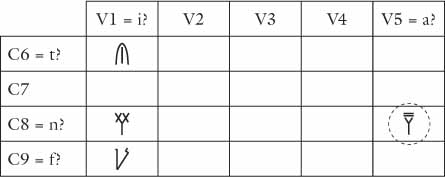

had the same value, then he could insert “na” into the grid where Row C8 and Column V5 intersected—in the cell whose “phonetic coordinates” were the consonant “n” and the vowel “a.” (On his grid, Ventris draws the character as  , an acceptable variant form.) Simplified, the relevant portion of his grid now looked like this:

, an acceptable variant form.) Simplified, the relevant portion of his grid now looked like this:

Ventris’s third grid. The sign  , “na,” placed at the intersection of Row C8 and Column V5 and indicated by an arrow, provided one of the first important clues to names inscribed on the tablets.

, “na,” placed at the intersection of Row C8 and Column V5 and indicated by an arrow, provided one of the first important clues to names inscribed on the tablets.

Turning again to the Cypriot syllabary, Ventris tried assigning the sound-value “ti” to the Linear B sign  , analogous to Cypriot

, analogous to Cypriot  . As it happened, he had already placed

. As it happened, he had already placed  exactly where it ought to be: at the intersection of C6 (“t”) and V1 (“i”). Now the grid’s web of interdependencies truly began to pay dividends: His correct placement of

exactly where it ought to be: at the intersection of C6 (“t”) and V1 (“i”). Now the grid’s web of interdependencies truly began to pay dividends: His correct placement of  automatically gave Ventris the value for

automatically gave Ventris the value for  (“ni”) in the same column. The word

(“ni”) in the same column. The word  so far was pronounced like this:

so far was pronounced like this:

To Ventris, the word looked more and more like “aminiso,” a syllabic spelling of “Amnisos.” It was one of the place-names that had seemed to suggest itself when he first tried the experiment in February. If that were the case, then the word’s second character,  , was “mi.” (Ventris’s initial placement of that sign as “fi” on the grid was incorrect.) Likewise,

, was “mi.” (Ventris’s initial placement of that sign as “fi” on the grid was incorrect.) Likewise,  was “so.”

was “so.”

Reading as  as “a-mi-ni-so” immediately gave Ventris two more characters to plug into the grid. Those in turn gave him values for all the consonants in Row 7 (“s”) and Row 9 (“m”), and for all the vowels in Column 2 (“o”):

as “a-mi-ni-so” immediately gave Ventris two more characters to plug into the grid. Those in turn gave him values for all the consonants in Row 7 (“s”) and Row 9 (“m”), and for all the vowels in Column 2 (“o”):

He now turned to  , another “place-name” he had toyed with in February. From his revised grid, he knew that the third syllable was “so”:

, another “place-name” he had toyed with in February. From his revised grid, he knew that the third syllable was “so”:

He had already placed the symbol  at Row C8, Column V2, which gave it the value “no.” If this were correct, the word now looked like this:

at Row C8, Column V2, which gave it the value “no.” If this were correct, the word now looked like this:

The incomplete word suggested a Cretan place-name—and not just any place-name but the single most important one on the island: Knossos, spelled syllabically as “ko-no-so.” This let Ventris position  correctly on the grid, where “k” and “o” meet:

correctly on the grid, where “k” and “o” meet:

Without the grid, identifying a name here or there would have yielded little additional return. With it, each new value “forced out” others, in precisely the kind of chain reaction Kober had foreseen. As a result, the third name Ventris had examined in February,  , could be read as “tu-ri-so,” the Linear B spelling of Tulissos, also a Cretan town. As new sound-values burst from the grid, Ventris was able to read additional Cretan place-names in the Knossos inscriptions, including

, could be read as “tu-ri-so,” the Linear B spelling of Tulissos, also a Cretan town. As new sound-values burst from the grid, Ventris was able to read additional Cretan place-names in the Knossos inscriptions, including  = “pa-i-to” (Phaistos) and

= “pa-i-to” (Phaistos) and  = “ru-ki-to” (Luktos). Once again, proper names had come to a decipherer’s rescue. Ventris’s great intuitive leap had proved correct: Kober’s triplets represented the “alternative name-endings” of Cretan towns. That was his second significant contribution. Greek place-names alone, as Ventris knew, didn’t prove that the language of the tablets was Greek. They could have been survivals carried over into Greek from an earlier, indigenous language— Ventris still held out for Etruscan. But in the coming weeks, as he worked the grid more deeply and new words emerged, he began to see something quite different from Etruscan. The process was like watching a photograph swim into being in a developers’ tray, though what was coming to the surface didn’t look much like Greek, either. Then again, of all the languages in the world that might be written with a syllabary, Greek is one of the worst candidates there is.

= “ru-ki-to” (Luktos). Once again, proper names had come to a decipherer’s rescue. Ventris’s great intuitive leap had proved correct: Kober’s triplets represented the “alternative name-endings” of Cretan towns. That was his second significant contribution. Greek place-names alone, as Ventris knew, didn’t prove that the language of the tablets was Greek. They could have been survivals carried over into Greek from an earlier, indigenous language— Ventris still held out for Etruscan. But in the coming weeks, as he worked the grid more deeply and new words emerged, he began to see something quite different from Etruscan. The process was like watching a photograph swim into being in a developers’ tray, though what was coming to the surface didn’t look much like Greek, either. Then again, of all the languages in the world that might be written with a syllabary, Greek is one of the worst candidates there is.

Greek screams for an alphabet. It is to the Greeks—who encountered the Phoenician alphabet at the start of the first millennium B.C., knew a good thing when they saw it, and improved upon it further—that we owe our own Roman alphabet, so handy for writing English. A “CV” syllabary like Linear B, on the other hand, which represents consonants and vowels in march-time alternation, is far less suited for writing Greek. Greek is a clatter of consonant clusters. (Consider, for example, the Classical Greek verb epémfthēn, “I was sent,” fairly choked with contiguous consonants.) The language is also rife with side-by-side vowels, as at the beginning—and end—of the noun oikía, “house.” For such words, too, Linear B is generally ill-equipped.

It had been understood since Evans’s time that Linear B was an outgrowth of Linear A. Most investigators, including Evans and Ventris, thought the scripts wrote the same language. But what if they didn’t? What if Linear B represented not the indigenous tongue of Minoan Crete but the language of later mainland colonizers? In that scenario, the invaders, unexposed to writing till they poured into Crete, seized the existing Minoan system for their own use. But if their native language was ill-suited to a syllabary, they would have needed to put the Cretan script through a set of compensating gyrations.

Though Ventris had held fast to his “Etruscan solution” since he was barely out of short pants, by the spring of 1952 he realized that he had to consider an alternative scenario: that the language of Linear B was not an indigenous Cretan tongue, but a Mycenaean import. That account would vindicate the few scholars, including Kober and Bennett, who thought the languages of Linear A and Linear B were different. It would also explain the presence of the B script on the mainland, brought back by victorious conquistadors for use at home.

Ventris began to wonder: Were the peculiar “spellings” of Linear B words the result of Cretan scribes having to force the square peg of the script into the round hole of a language for which it was never intended? Over the coming weeks, he worked out a set of “spelling rules” by which Linear B might have been used to write a non-Cretan tongue. The elucidation of these rules was his third major contribution. Among them were these:

One rule concerned the deletion of final consonants in Linear B words. Perhaps the most distinctive “fingerprint” of Classical Greek spelling is that words nearly always end in a vowel, or in one of a small set of consonants: “l,” “m,” “n,” “r,” or “s.” When a “CV” syllabary is used to write such a language, it immediately runs into trouble, because it can’t spell words that end in consonants. The scribe then has two options: He can insert a “dummy” vowel at the end of the word. (In such a system, the English word cat might be spelled “ca-ta.”) Alternatively, he can delete final consonant altogether. (In this case, cat becomes “ca.”)

Linear B chose the second alternative, and the word po-lo, so tartly dismissed by Evans, is a perfect example of the rule in action. The word was indeed pōlos (“foal”), impeccably respelled in Linear B. The problematic final “s” was simply lopped off, as the script’s syllabic spelling rules dictated.

Strikingly, the Cypriot syllabary, when conscripted to spell Greek, made the opposite—though equally valid—choice. Instead of deleting final consonants, it tacked a “dummy” vowel on to the ends of words as needed: In Cypriot spelling, the Greek word doulos (“slave”), for instance, would have been written do-we-lo-se, with the final “e” serving as the dummy vowel. (In Linear B, by contrast, the same word is spelled do-e-ro.)

This difference in the handling of final consonants was the primary reason the Cypriot clue had been deemed useless for Linear B. As expected, Cypriot inscriptions in Greek contained a bevy of words ending in “se,” written by means of the character . (These were words, like doulos, that actually ended in “s” in Greek.) If Linear B also wrote Greek, scholars reasoned, the tablets should be filled with words that ended with the corresponding character,

. (These were words, like doulos, that actually ended in “s” in Greek.) If Linear B also wrote Greek, scholars reasoned, the tablets should be filled with words that ended with the corresponding character,  . But as the statistics of Kober, Ventris, and other investigators revealed,

. But as the statistics of Kober, Ventris, and other investigators revealed,  did not appear at the ends of Linear B words especially often. This reinforced the prevailing notion that the script wrote a non-Greek language.

did not appear at the ends of Linear B words especially often. This reinforced the prevailing notion that the script wrote a non-Greek language.

Another “spelling rule” noted by Ventris concerned Linear B’s use of dummy vowels to break up Greek consonant clusters. The rule is at work in the very first syllable of “Knossos.” Written in Linear B, the word is “ko-no-so,” with the “o” of the first syllable intervening between the “k” and the “n.” (Note, too, that the final “s” has been deleted, exactly as Linear B’s spelling rules predict.)

Applying these rules and others, Ventris found he could read still more words. Among them were  and

and  , the words for “total.” His grid gave them the values “to-so” and “to-sa”—perfect Linear B spellings of the Classical Greek words tossoi and tossai, the masculine and feminine plural forms of the word meaning “so much.” The Linear B signs for “boy” (

, the words for “total.” His grid gave them the values “to-so” and “to-sa”—perfect Linear B spellings of the Classical Greek words tossoi and tossai, the masculine and feminine plural forms of the word meaning “so much.” The Linear B signs for “boy” ( ) and “girl” (

) and “girl” ( ) came out as “ko-wo” and “ko-wa,” which suggested kouros and korē, the masculine and feminine singular forms of the Greek word for “child.”

) came out as “ko-wo” and “ko-wa,” which suggested kouros and korē, the masculine and feminine singular forms of the Greek word for “child.”

It was these words more than anything that forced Ventris to abandon his cherished “Etruscan solution” once and for all. “To-so” and “to-sa,” along with “ko-wo” and “ko-wa,” strongly suggested that the language of the tablets inflected its words for gender, much as French or Spanish does. Gender inflection is a hallmark of the Indo-European language family, to which languages like French, Spanish, German, Latin, and Greek belong. (What is more, -o and -a serve as masculine and feminine endings in a spate of Indo-European languages.) The presence of gender inflection in the tablets suggested a language other than Etruscan: Etruscan was non-Indo-European, and from everything scholars had gleaned about its grammar, it did not inflect words for gender.

In the coming weeks, Ventris pinpointed additional words, including  , “po-me” (like Classical Greek poimēn, “shepherd”);

, “po-me” (like Classical Greek poimēn, “shepherd”);  , “ke-ra-me-u” (kerameus, “potter”; think of the English word ceramics);

, “ke-ra-me-u” (kerameus, “potter”; think of the English word ceramics);  , “ka-ke-we” (khalkēwes, “bronze-smith”); and

, “ka-ke-we” (khalkēwes, “bronze-smith”); and  , “te-ko-to-ne” (tektones, “carpenters”; compare English tectonic, which likewise has to do with the fitting together of things). Each new word meant new sound-values for the grid. These in turn generated other values.

, “te-ko-to-ne” (tektones, “carpenters”; compare English tectonic, which likewise has to do with the fitting together of things). Each new word meant new sound-values for the grid. These in turn generated other values.

On June 1, 1952, Ventris composed the twentieth and last in his series of Work Notes. This, his most famous Note, bears a title at once bold and tentative: “Are the Knossos and Pylos Tablets Written in Greek?” Just five pages long—far shorter than many previous Notes—Work Note 20 betrays the author’s deep ambivalence about the solution that was massing unbidden before his eyes. “In the chains of deduction which spread out,” Ventris wrote, “we may, I believe, initially strike words and forms which force us to ask ourselves whether we are not, after all, dealing with a Greek dialect.”

Then, in the very next paragraph, he retreats, writing, “These may well turn out to be a hallucination.” He then continues: “If we were to toy with the idea of an early Greek dialect, we should have to assume that a Greek ruling class, appearances to the contrary, established itself at Knossos as early as 1450, and that the new Linear B was adapted from the indigenous syllabary in order to write Greek.”

Over the next several pages, Ventris lays out the results of his place-name experiments before closing with a final retreat: “If pursued, I suspect that this line of decipherment would sooner or later come to an impasse, or dissipate itself in absurdities; and that it would be necessary to revert to the hypothesis of an indigenous, non-Indo-European language.”

But over the next few days, try though he might to suppress it, Greek kept asserting itself. One night in early June, he found he could no longer fend it off. That night, the journalist Prue Smith and her husband had been invited to dine at the Ventrises’ flat; Smith’s husband, also an architect, was a colleague. When they arrived, as she recounts in her memoir, Michael Ventris was nowhere to be seen:

Lois Ventris, whom we always called Betts, talked amiably, apologising at fairly frequent intervals for her husband’s absence—he was in his study, she said, and would come as soon as he could. We grew a little hungry, and a little drunk on the pre-prandial sherry, and Betts a little anxious and embarrassed. After what seemed a very long time Michael burst into the room, full of apologies but even more full of excitement. “I know it, I know it,” he said, “I am certain of it——.” I thought he must have confirmed an earlier idea that the language was Etruscan. But what he had proved, of course, was that the language was an early form of Greek … recorded on the earliest known documents of European civilisation.

After spending half his life on the problem, Michael Ventris, a month shy of his thirtieth birthday, had solved the riddle of Linear B. But before long, just as the script itself had, the consequences of being its decipherer would start to consume him.