Knossos, Crete, 1900

THE TABLET, WHEN IT EMERGED from the ground, was in nearly perfect condition. A long, narrow rectangle of earthen clay, it tapered toward the ends, resembling a palm leaf in shape. One end was broken: That was not surprising, after three thousand years. But the rest of the tablet was intact, and on it, inscribed numbers were plainly visible. Alongside the numbers was a series of bewildering symbols, which looked like none ever seen.

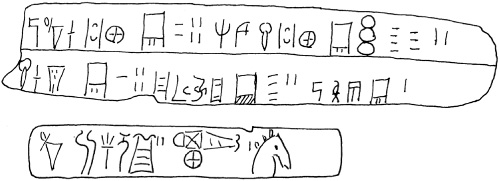

In the coming weeks, workmen would lift from the earth dozens more tablets, some fractured beyond repair, others completely undamaged. All were incised with the same curious symbols, including these:

The tablets were what Arthur Evans had come to Crete to find. It had taken him only a week to locate the first one, but his discovery would forever change the face of ancient history.

ON MARCH 23, 1900, Evans, a few carefully chosen assistants, and thirty local workmen had broken ground at Knossos, in the wild countryside of northern Crete near present-day Heraklion. There, not far from the sea, on a knoll bright with anemones and iris, Evans had vowed years earlier that he would dig.

He was rewarded almost immediately. Even before the first week was out, his workmen’s spades turned up fragments of painted plaster frescoes in still-vivid hues, depicting scenes of people, plants, and animals. Digging deeper, they found pieces of enormous clay storage jars that reassembled would stand tall as a man. Still farther down, they encountered rows of huge gypsum blocks, the walls of a vast prehistoric building.

Evans had come upon the ruins of a sophisticated Bronze Age civilization, previously unknown, that had flowered on Crete from about 1850 to 1450 B.C. Predating the Greek Classical Age by a thousand years, it was the oldest European civilization ever discovered.

At forty-eight, Arthur Evans was already one of the foremost archaeologists in Britain. His discovery at Knossos, which the newspapers swiftly relayed around the globe, would make him among the most celebrated in the world. For the sprawling building beneath the knoll, he soon concluded, was none other than the palace of Minos, the legendary ruler of Crete, who crops up centuries later in Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

As Classical Greek myth told it afterward, King Minos had presided over a powerful maritime empire centered at Knossos. He held court in a huge palace resplendent with golden treasures and magnificent works of art, oversaw a thriving economy, and controlled the Aegean after making its waters safe from piracy. He was said to have installed an immense mechanical man, known as Talos and made of bronze, to patrol the Cretan shore and hurl rocks at approaching enemy ships.

It was for Minos, legend held, that the architect Daedalus had built the Cretan labyrinth, which housed at its center the fearsome Minotaur—half-man, half-bull. And it was Minos’s daughter, Ariadne, with her ball of red thread, who helped her lover, Theseus, escape from the labyrinth, where he had been sent to be sacrificed. As Evans’s prolonged excavation would reveal, the palace at Knossos spanned hundreds of rooms linked by a network of twisting passages. Surely, he would write, this vast complex was the historic basis of the enduring myth of the labyrinth.

Unseen for nearly three thousand years, the Knossos palace was hailed as one of the most spectacular archaeological finds of all time, “such a find,” Evans wrote, “as one could not hope for in a lifetime or in many lifetimes.” In his first season alone, he uncovered an exquisite marble fountain shaped like the head of a lioness, with eyes of enamel; carvings of ivory and crystal; ornate stone friezes; and, still more impressive, a carved alabaster throne, the oldest in Europe.

But these treasures paled beside what Evans found on the excavation’s eighth day. On March 30, a workman’s spade dislodged the first clay tablet. On April 5, a whole cache of tablets, many in perfect condition, was found in a single room of the palace.

The tablets, when Evans unearthed them, were Europe’s earliest written records. Inscribed with a stylus when the clay was still wet, they dated to about 1450 B.C., nearly seven centuries before the advent of the Greek alphabet. The characters they contained—outline drawings in the shape of human figures, swords, chariots, and horses’ heads, among other tiny pictograms—resembled the symbols of no known alphabet, ancient or modern.

Linear B tablets from Knossos.

Evans named the ancient writing Linear Script Class B— Linear B, for short. (He also turned up evidence of a somewhat older Cretan script, likewise based on outline drawings, which he called Linear Script Class A.) By the end of his first season’s dig, he had unearthed more than a thousand tablets written in Linear B.

Though Evans couldn’t read the tablets, he immediately surmised what they were: administrative records, carefully set down by royal scribes, documenting the day-to-day workings of the Knossos palace and its holdings. If the tablets could be decoded, they would open a wide portal onto the daily life of a refined, wealthy, and literate society that had thrived in Greek lands a full millennium before the glory of Classical Athens. Once their written records could be read, the Knossos palace and its people, languishing for thirty centuries in the dusk of prehistory, would suddenly be illuminated—with a single stroke, an entire civilization would become history.

But which civilization was it? As Evans well knew, many ethnic groups had passed through the Bronze Age Aegean, and there was no way to tell whose language, and whose culture, Linear B represented. To him, though, this seemed a small impediment. Evans was already something of an authority on ancient scripts, and with characteristic assurance, he assumed he would one day decipher this one. By 1901, only a year after the first tablet was unearthed, he had commissioned Oxford University Press to cast a special font, in two different sizes, with which to typeset the Cretan characters.

But Evans underestimated the formidable challenge Linear B would pose. An unknown script used to write an unknown language is a locked-room mystery: Somehow, the decipherer must finesse his way into a tightly closed system that offers few external clues. If he is very lucky, he will have the help of a bilingual inscription like the Rosetta stone, which furnished the key to deciphering the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt. Without such an inscription, his task is all but impossible.

As Evans could scarcely have imagined in 1900, Linear B would become one of the most tantalizing riddles of the first half of the twentieth century, a secret code that defied solution for more than fifty years. As the journalist David Kahn has written in The Codebreakers, his monumental study of secret writing, “Of all the decipherments of history, the most elegant, the most coolly rational, the most satisfying, and withal the most surprising” was that of Linear B.

The quest to decipher the tablets—or even to identify the language in which they were written—would become the consuming passion of investigators around the globe. Working largely independently in Britain, the United States, and on the European continent, each spent years trying to tease the ancient script apart. The best of them brought to the problem the same meticulous forensic approach that helps cryptanalysts crack the thorniest codes and ciphers.

No prize was offered for deciphering Linear B, nor were the investigators seeking one. For some, like Evans, the chance to read words set down by European men three thousand years distant was compensation enough. For others, the sweet, defiant pleasure of solving a cryptogram many experts deemed unsolvable would be its own best reward.

Today, in an era of popular nonfiction that professes to find secret messages lurking in the Hebrew Bible, and of novels whose valiant heroes follow clues encoded in great works of European art, it is bracing to recall the story of Linear B—a real-life quest to solve a prehistoric mystery, starring flesh-and-blood detectives with nothing more than wit, passion, and determination at their disposal.

Over time, two besides Evans emerged as best equipped to crack the code. One, Michael Ventris, was a young English architect with a mournful past, whose fascination with ancient scripts had begun as a boyhood hobby. The other, Alice Kober, was a fiery American classicist—the lone woman among the serious investigators—whose immense contribution to the decipherment has been all but lost to history. What all three shared was a ferocious intelligence, a nearly photographic memory for the strange Cretan symbols, and a single-mindedness of purpose that could barely be distinguished from obsession. Of the three, the two most gifted would die young, one under swift, strange circumstances that may have been a consequence of the decipherment itself.

Considered one of the most prodigious intellectual feats of modern times, the unraveling of Linear B has been likened to Crick and Watson’s mapping of the structure of DNA for the magnitude of its achievement. The decipherment was done entirely by hand, without the aid of computers or a single bilingual inscription. It was accomplished, crumb by crumb, in the only way possible: by finding, interpreting, and meticulously following a series of tiny clues hidden within the script itself. And in the end, the answer to the riddle defied everyone’s expectations, including the decipherer’s own.

To Ventris, the solution brought worldwide acclaim. But before long it also brought doubt, despair, personal and professional ruin, and, some observers believe, untimely death.

All this was decades in the future that March day at Knossos, when the first brittle tablets emerged from the ground. But of one thing Arthur Evans was already certain. Guided by the smallest of clues, he had come to Crete in search of writing from a time before Europe was thought to have writing. And there, he now knew beyond doubt, he had found it.