Jesus Comes to His Own

By the end of Mark 5, an enormous momentum has been created. Jesus has traveled throughout Galilee and beyond, proclaiming the kingdom and demonstrating its presence with healings, exorcisms, a spectacular feat subduing the elements of nature, and even the raising of a dead child. Despite some fierce opposition from the religious authorities, the advance of the kingdom still looks like a triumphal march. Crowds of people have experienced liberation, healing, and the tender compassion of Jesus. But at the beginning of chapter 6, this activity suddenly comes to a grinding halt. The mighty works that hostile opponents, demons, diseases, and even death could not stop, are blocked—temporarily—by a greater obstacle: unbelief. It is not that Jesus’ power is limited, but people are hindered from experiencing his power by their refusal to believe in him.

Yet the meager results of the mission in Jesus’ own hometown are more than outweighed by the abundant fruit of the mission on which he now sends his apostles. By the end of this section, no longer Jesus alone but now his apostles bring healing, freedom, and new life to multitudes of people. It is the debut of the mission of the Church.

1He departed from there and came to his native place, accompanied by his disciples. 2When the sabbath came he began to teach in the synagogue, and many who heard him were astonished. They said, “Where did this man get all this? What kind of wisdom has been given him? What mighty deeds are wrought by his hands! 3Is he not the carpenter, the son of Mary, and the brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon? And are not his sisters here with us?” And they took offense at him. 4Jesus said to them, “A prophet is not without honor except in his native place and among his own kin and in his own house.” 5So he was not able to perform any mighty deed there, apart from curing a few sick people by laying his hands on them. 6He was amazed at their lack of faith.

He went around to the villages in the vicinity teaching.

NT: Mark 3:20–21, 31–35; John 6:42; 7:5. // Matt 13:54–58; Luke 4:16–30

Catechism: brothers of Jesus, 500; laying on hands, 699; prayer with faith, 2610

6:1–2 Jesus returns for the first time in the Gospel to his native place, Nazareth (1:9, 24). Nazareth was a small, insignificant village (see John 1:46) of not more than a few hundred inhabitants. In this place where one might expect the warmest welcome and most enthusiastic acclaim, he meets a very different response. According to his usual custom (Mark 1:21, 39; 3:1), on the sabbath Jesus enters the synagogue to teach. At first the villagers seem to react in the same way as other audiences: they are astonished at his wisdom and authority (1:22; 11:18). But in this case it is an astonishment at what seems inappropriate and out of place to them. To their minds Jesus is just “one of the guys,” someone they have known all their lives. They had never seen anything extraordinary about him. All this itinerant preaching and miracle-working seems to them to be putting on airs. Where did this man get all this? Their questions display not a sincere pursuit of truth but rather indignant skepticism. They are asking the right questions, which all the readers of the Gospel are meant to ask, but with the wrong attitude. They cannot accept that the answer might be “from God.” Wisdom and mighty deeds (dynameis) are attributes of God himself (Jer 10:12; 51:15; Dan 2:20), and Scripture often refers to the great deeds accomplished by God’s “hand” (Exod 32:11; Deut 4:34; 7:19). But the people cannot bring themselves to draw the logical conclusion of their reasoning.

6:3 The villagers deem that Jesus’ hands would be put to better use by returning to his former occupation: woodworking (the Greek word for carpenter, tektōn, can also mean builder or craftsman). Their reference to Jesus’ family members by name shows their close familiarity with his background. Only in Mark is Jesus referred to as the son of Mary, an unusual designation since Jews customarily referred to sons in relation to their fathers (Matt 16:17; Mark 10:35). It may have been a veiled slur, alluding to the fact that Mary was not yet married at the time of Jesus’ conception (see John 8:41), or perhaps simply an indication that Joseph was deceased. Their questions suggest that they have pigeonholed Jesus: they are confident that they know all there is to know about him. So they took offense at him (skandalizomai, meaning to stumble over an obstacle). The idea that their hometown carpenter, Jesus, could be inaugurating the kingdom of God was scandalous; it did not conform to their preconceived ideas about how God would and could act. And their attachment to their preconceived ideas became an obstacle to faith. Like the “outsiders” described earlier, they “look and see but do not perceive, and hear and listen but do not understand” (Mark 4:12).

6:4 Jesus replies to their outburst with a proverbial saying that, in one form or another, was current in his time: A prophet is not without honor except in his native place and among his own kin and in his own house (Luke 4:24; John 4:44). By referring to himself as a †prophet Jesus links his destiny to that of the long line of Old Testament prophets who suffered rejection or violence because of the unpopularity of their message.[1] He is held without honor in circles of increasing intimacy: among his townspeople, his relatives, and even his household. Their failure to accept him is symbolic of the rejection of his people: “He came to what was his own, but his own people did not accept him” (John 1:11; see Luke 13:34–35).

6:5–6 So acute is the people’s unbelief that Jesus is unable to perform any mighty deed, apart from curing a few sick people. Unlike Matthew and Luke, Mark does not soften or omit this statement that seems to limit the power of the Son of God. Mark wishes to highlight the necessity of faith—at least a basic openness to God’s power at work in Jesus—as the proper disposition for receiving his healing. Despite the atmosphere of unbelief in Nazareth, however, Jesus cures a few people, once again by his personal touch (see 1:31, 41; 5:23, 28). He is amazed at the people’s lack of faith (or “unbelief,” RSV)—ironically, he shows the same emotion that characterizes others’ positive reaction to his miracles (5:20; see Luke 8:25). Few things cause as strong a human reaction in Jesus as a lack of faith, or conversely, great faith (see Matt 8:10; 15:28). Faith is his door into human hearts, but it can be opened only from within.

Following this episode, Jesus continues his ministry in the surrounding villages. Mark emphasizes Jesus’ mission of teaching, but by now his readers understand it is a “teaching with authority” that includes healing the sick and expelling demons (see Mark 1:27).

Reflection and Application (6:1–6)

It would be easy to judge the townspeople of Nazareth. How could they have been so blind as to fail to recognize the Messiah in their midst? But it is impossible to say who would not have reacted similarly in the same circumstances. This incident reveals the “extraordinary ordinariness” of the Son of God. He lived a life so lowly, unassuming, and unremarkable that the possibility that the omnipotent God was present in him was simply incomprehensible to many who knew him. It is not the first time that the lowly ways of God have perplexed and disconcerted his people (Judg 6:14–15; 1 Kings 19:11; Mic 5:1). Isaiah had prophesied a Suffering Servant of God who, before his great work of atonement, would grow up unrecognized in the midst of the people (Isa 53:2). God desired his work of redemption, the reconciliation of humanity with himself, to come not from without but from within: our redeemer is one of us (see Heb 2:11, 17).

The Mission of the Twelve (6:7–13)

7He summoned the Twelve and began to send them out two by two and gave them authority over unclean spirits. 8He instructed them to take nothing for the journey but a walking stick—no food, no sack, no money in their belts. 9They were, however, to wear sandals but not a second tunic. 10He said to them, “Wherever you enter a house, stay there until you leave from there. 11Whatever place does not welcome you or listen to you, leave there and shake the dust off your feet in testimony against them.” 12So they went off and preached repentance. 13They drove out many demons, and they anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them.

NT: 2 Cor 9:8; Phil 4:11–13; James 5:14–15. // Matt 10:1–15; Luke 9:1–6

Catechism: mission of the apostles, 2, 551, 858–60, 1122; anointing of the sick, 1499–523

6:7 The initial phase of the training of the Twelve is now complete, and they are ready to participate actively in the mission of Jesus—to become fishers of men (1:17). Their first task as †apostles was “to be with him” (3:14); the second is to be “sent out” (apostellō, from which “apostle” is derived) and carry out the same works Jesus himself has been doing. They have “been with” Jesus for some time and have witnessed his serene response to opposition (3:21–30; 6:1–6), his teaching in parables (4:1–34), and his prodigious miracles (4:35–5:43). By this point they must have trembled at the tall order given to them: to do the same mighty deeds. That Jesus began to send them out suggests that he did not send all twelve at once, but took time with each pair, ensuring that they were fully prepared and had confidence to begin their mission.

They were not to go alone but two by two, as little units of Christian community (see Matt 18:20), since their mission was to gather God’s people into a new community centered on Jesus (see Mark 3:34; John 11:52). The Church’s experience over the ages has confirmed the wisdom of this approach (see Acts 13:1–3; 15:39–40). A lone missionary is at risk of discouragement, danger, and temptation; but a pair of missionaries can pray together, encourage and support each other, correct each other’s mistakes, and discern how to deal with problems together. Moreover, in the law of Moses the testimony of two witnesses is necessary to sustain a criminal charge (Num 35:30; Deut 19:15); how much more the testimony to the gospel, on which eternal life is at stake (Mark 6:11). Again there is a strong emphasis on their task of expelling unclean spirits (3:15)—in fact, it is the only task mentioned here, suggesting that it sums up their whole ministry. They are granted a share in Jesus’ divine authority so as to advance his conquest of the realm of evil.

6:8–9 Jesus’ instructions regarding their traveling gear may strike us as rather austere. The apostles are to take nothing with them other than the clothing on their backs, sandals on their feet, and a walking stick.[2] A stick, or staff, is a biblical symbol for authority (Exod 4:20; Mic 7:14). The lack of a sack meant that they could not even accept provisions from others for the journey. Why is this poverty so important to their mission? Mark does not explain, but several reasons can be surmised. First, the apostles had to learn not to rely on their own resources but on God’s all-sufficient providence (see 2 Cor 9:8–10; Phil 4:11–13). Because they were occupying themselves with God’s work, God would occupy himself with their daily needs. Their bare simplicity of life, like that of John the Baptist (Mark 1:6), would help them stay free of distractions and focus wholly on their mission. Moreover, their need for food and shelter would call forth hospitality in those to whom they ministered, an important principle of early Church life (see Acts 16:15; Rom 12:13; 3 John 5–8). Finally, their lack of material possessions lent credibility to their message, since it demonstrated that they were preaching the gospel out of conviction rather than desire for gain. Peter was later able to say to the cripple at the temple gate, “I have neither silver nor gold, but what I do have I give you: in the name of Jesus Christ the Nazorean [rise and] walk” (Acts 3:6).

6:10 In the Jewish tradition of hospitality (see Gen 18:1–8; 19:1–3; Job 31:32), it was common for travelers to be welcomed spontaneously into homes along their way, especially since not every village boasted an inn. Jesus instructs the Twelve to stay in whatever house they enter, not moving about from house to house. The reason may be to avoid any rivalry or jockeying for prestige that could arise among villagers wishing to host them. Nor may the apostles upgrade their accommodations. Like Jesus, they were likely to be besieged by crowds once they began the ministry of healing and exorcism in a given town (see Acts 8:6), and staying in one place would limit unnecessary distractions.

6:11 The stakes involved in accepting or refusing the gospel are high. Jesus equates the response given to his apostles with a response to himself (see 9:37). To welcome them is to welcome him. And to refuse to listen is to forfeit his invitation to eternal life (see 8:38; 16:16; John 3:18). To shake the dust off one’s feet was a symbolic gesture of repudiation (Acts 13:51), meant as a solemn warning to those who rejected the apostles’ message. For Jews, the soil of Israel was holy (see 2 Kings 5:17; Isa 52:2); upon reentering the land after a journey they would shake the pagan dust off their feet as a sign of separating themselves from Gentile ways. This gesture would serve as a testimony against such unreceptive villages on the day of judgment. It is also a reminder to the apostles not to be discouraged by the resistance they will sometimes encounter. Their job is to carry out their mission obediently; success is in the hands of God. No one can be compelled to accept their message.

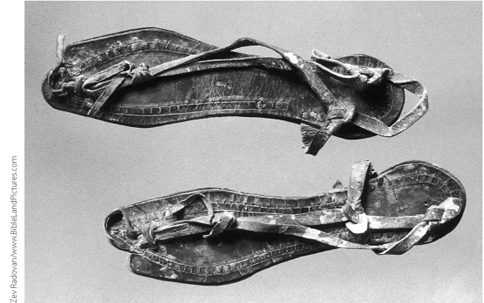

Fig. 6. Ancient sandals found at Masada.

The Church recognizes Mark 6:13 as part of the biblical basis for the Sacrament of the Sick, through which the Church continues to minister Jesus’ healing power to those in need of it. “Among the seven sacraments there is one especially intended to strengthen those who are being tried by illness, the Anointing of the Sick: ‘This sacred anointing of the sick was instituted by Christ our Lord as a true and proper sacrament of the New Testament. It is alluded to indeed by Mark, but is recommended to the faithful and promulgated by James the apostle and brother of the Lord’ ” (Catechism, 1511, quoting the Council of Trent).

6:12–13 Mark describes the apostles’ preaching in the simplest of terms: like John the Baptist (1:4), they preached †repentance (metanoia), the call to turn away from sin and toward God in a complete change of heart. The fullness of the Christian gospel, the victory of the crucified and risen Lord, can be proclaimed only after the resurrection. But their message, like that of Jesus, carries authority (6:7); it is accompanied by works of power that serve as visible signs confirming its truth. This is the only time in the Gospels that anointing with oil is mentioned in conjunction with curing the sick, although it later becomes a practice of the early Church (James 5:14). Oil was used for medicinal purposes (Luke 10:34), but here its sacramental value as a vehicle for divine healing is emphasized.

The Beheading of John the Baptist (6:14–29)

14King Herod heard about it, for his fame had become widespread, and people were saying, “John the Baptist has been raised from the dead; that is why mighty powers are at work in him.” 15Others were saying, “He is Elijah”; still others, “He is a prophet like any of the prophets.” 16But when Herod learned of it, he said, “It is John whom I beheaded. He has been raised up.”

17Herod was the one who had John arrested and bound in prison on account of Herodias, the wife of his brother Philip, whom he had married. 18John had said to Herod, “It is not lawful for you to have your brother’s wife.” 19Herodias harbored a grudge against him and wanted to kill him but was unable to do so. 20Herod feared John, knowing him to be a righteous and holy man, and kept him in custody. When he heard him speak he was very much perplexed, yet he liked to listen to him. 21She had an opportunity one day when Herod, on his birthday, gave a banquet for his courtiers, his military officers, and the leading men of Galilee. 22Herodias’s own daughter came in and performed a dance that delighted Herod and his guests. The king said to the girl, “Ask of me whatever you wish and I will grant it to you.” 23He even swore [many things] to her, “I will grant you whatever you ask of me, even to half of my kingdom.” 24She went out and said to her mother, “What shall I ask for?” She replied, “The head of John the Baptist.” 25The girl hurried back to the king’s presence and made her request, “I want you to give me at once on a platter the head of John the Baptist.” 26The king was deeply distressed, but because of his oaths and the guests he did not wish to break his word to her. 27So he promptly dispatched an executioner with orders to bring back his head. He went off and beheaded him in the prison. 28He brought in the head on a platter and gave it to the girl. The girl in turn gave it to her mother. 29When his disciples heard about it, they came and took his body and laid it in a tomb.

OT: 1 Kings 19:2; Sir 48:9–12; Mal 3:23–24

NT: Mark 9:11–13. // Matt 14:1–12; Luke 3:19–20; 9:7–9

Catechism: John the Baptist, 523, 717–20

Lectionary: Martyrdom of St. John the Baptist

Between the accounts of the apostles setting out on their mission and returning from it, Mark inserts an interlude: the sordid story of Herod’s banquet and his execution of John the Baptist. The placement of this episode is by no means accidental. As Mark already hinted in 1:14, John’s life is in a mysterious way patterned on that of Christ; his death foreshadows Jesus’ death. The passion of John recounted here coincides with the first mission of the apostles, as the passion of Jesus will give birth to the Church’s mission in which the gospel is proclaimed to the whole world.[3] With this parallel Mark suggests that John’s self-offering shares, in a hidden way, in the spiritual fruitfulness of the sacrifice of Christ.

6:14–16 Herod heard about the apostles’ mission, because Jesus’ fame (literally, his name) had become widespread. Like the seed that falls on the path (4:15), Herod’s hearing of the word about Jesus will be fruitless, since it does not take root in him. The rumors circulating about Jesus, later repeated in 8:28, illustrate widespread spiritual confusion. Some people held that Jesus was a resurrected John the Baptist, a strange opinion since Jewish tradition accepted belief in a general resurrection at the end of the age, not in a dead individual returning to earth. The view that mighty powers are at work in him attributes paranormal or occult phenomena to Jesus, as if he is inhabited by good powers just as demoniacs are inhabited by evil ones. Others held that he was Elijah, not recognizing in Jesus the transcendent fulfillment of all that Elijah and John the Baptist had prophesied. Yet another opinion maintained that Jesus was a †prophet like any of the prophets. Indeed he was (6:4), but not merely another of the Old Testament prophets; he was the definitive prophet promised by Moses (Deut 18:18), who would impart all that God wanted to reveal to his people. All these opinions remain fixated in the wise words and wondrous works done by Jesus, and fail to arrive at the person revealed through those words and deeds. Perhaps Herod, plagued with a guilty conscience for his execution of the innocent John, was susceptible to superstitious fears and thus opted for the first opinion, that Jesus is actually John whom he beheaded.

Herod and Herodias

The Herod who reigned during Jesus’ public ministry was Herod Antipas, client ruler under the Roman emperor of the regions of Galilee and Perea. Antipas was one of the many sons of Herod the Great, who had been known for his great building projects (including the renovation of the temple) and his brutal murders (including the slaughter of the innocents, Matt 2:16). After his father’s death in 4 BC, Antipas was appointed “tetrarch,” or ruler, over a quarter of the kingdom.

The Herodian family history reads like an ancient soap opera. Antipas was a half-uncle to Herodias, daughter of his half-brother. She was originally married to a different half-uncle, Herod Philip (Mark 6:17; Luke 3:1). Her daughter Salome was born of that union. Both Antipas and Herodias divorced their first spouses to marry each other, after living for some time in open adultery. Besides the execution of John, this act also precipitated a war between Antipas and his first wife’s father, leading to Antipas’s downfall and exile in AD 39.[a]

6:17–18 At this point Mark gives his readers a flashback describing in detail how the Baptist met his demise. John had incurred the wrath of the ruling family by publicly denouncing their adulterous conduct. Herod had divorced his first wife to marry his brother’s wife Herodias, and John boldly admonished them for this unlawful union (see Lev 20:21). His baptism of †repentance (Mark 1:4) was no mere ritual; it was a call for the whole people to radically turn away from sin. John recognized that the behavior of political leaders had a powerful impact on the moral environment of the country at large. The Herodian scandal would dull the consciences of the people and put obstacles in the way of the “straight path” God was preparing for the Messiah (1:3). Like the prophets of old, John was willing to risk his life for his message.

6:19–20 John’s admonition earned him the bitter resentment of Herodias, who wanted to kill him. Herod, however, was ambivalent. He had a mild religious curiosity and liked to listen to John but did not actually take his words seriously. To placate his wife, Herod had John arrested but still listened to his preaching in fascination and perplexity. Ironically the powerful ruler living in decadent luxury was afraid of the austere prophet from the desert. Herod’s reaction to John was remarkably similar to that of King Ahab to John’s predecessor Elijah many centuries before. Like John, Elijah had publicly rebuked the king for a sin urged on him by his wife, Queen Jezebel (1 Kings 21:1–29). Although Ahab gave Elijah a hearing, Jezebel furiously plotted to kill him (1 Kings 19:1–3).

6:21–23 Unlike Jezebel, Herodias found the opportunity to destroy the man she hated. To celebrate his birthday (a secular rather than a Jewish custom), Herod invited his courtiers (top government officials), military officers, and the leading men of Galilee (social elites, probably the Herodians mentioned in 3:6; 12:13). It became a banquet of death, in contrast to the banquet of life Jesus had celebrated with the outcasts and repentant sinners of Galilee (2:15). Herodias’s daughter, Salome, performed a dance—probably a seductive display that would have been highly unusual for a royal princess but not implausible in an all-male party that doubtless included abundant alcohol. In an excess of delight, Herod attempted to impress his guests by making grandiose promises and even “oaths” to the young girl. Offering half his kingdom was merely an expression of extravagance (see Esther 5:6; 7:2); Herod, as a client of Rome, did not have power to subdivide his kingdom.

6:24–29 Prompted by her mother, whom she seemed to take after, the girl made her gruesome request: I want … the head of John the Baptist. Her enthusiasm for this request is shown by her own additional touches—at once, on a platter—to guarantee that the macabre deed would be carried out before her stepfather had time to change his mind. Herod instantly realized the foolishness of his oaths. But valuing the admiration of his guests more than an innocent man’s life, he acceded to the girl’s request. The executioner, having efficiently carried out his orders, brought in the head on a platter, as if it were the next course in Herod’s birthday banquet. When they heard what happened, the Baptist’s disciples took his body and gave him an honorable burial, foreshadowing the proper burial given to Jesus (15:46).

Reflection and Application (6:14–29)

Readers might wonder why Mark has spent so much time on this chilling episode, the only sustained narrative in his Gospel that is not directly about Jesus. Perhaps it is to highlight the passion of John as a foreshadowing of the passion of Christ. Herod’s actions show the snowball effect of unchecked sin, a common biblical theme (see Gen 4:5–8; 2 Sam 11; James 1:14–15). From adultery Herod progressed to debauchery and ultimately, via his rash oaths, to murder. Like Pilate later in the Gospel, Herod holds no malice toward his victim, yet cowardice and excessive concern for his own reputation lead him to bloodshed. Each player in the drama is complicit in the evil: his scheming wife, her lascivious daughter, the ruthlessly efficient executioner, and even Herod’s dissipated guests, who raise no protest against the death of the innocent. Similarly, all the players in the passion of Jesus—and by extension, all of sinful humanity—are complicit in the death of the Son of God. Jesus, like John, will meet his end because he confronts people with the hard but salutary truth about God’s claim on our lives and the call to †repentance that is the doorway to salvation. The success of the apostles’ first mission, which immediately follows John’s death, is a symbolic anticipation of the countless multitudes who will enter the kingdom as a fruit of the death of Christ—and of the witness of Christian martyrs, who testify to the gospel at the cost of their lives (see Mark 10:45; 14:24; Rev 12:11).

The Return of the Twelve (6:30–32)

30The apostles gathered together with Jesus and reported all they had done and taught. 31He said to them, “Come away by yourselves to a deserted place and rest a while.” People were coming and going in great numbers, and they had no opportunity even to eat. 32So they went off in the boat by themselves to a deserted place.

OT: Exod 33:14; Deut 12:10; Isa 40:31

NT: 2 Cor 11:27. // Luke 9:10–11

Catechism: rest, 2184

Lectionary: 6:30–34: Mass for a Council or Synod or a Spiritual or Pastoral Meeting

6:30 After the interlude on the death of John the Baptist, Mark picks up where he left off with the mission of the †apostles (6:7–13), who now return to Jesus and report to him all they had done and taught. Although Jesus’ recent instructions (6:7–11) did not mention teaching, it was part of the ministry for which he had appointed them (3:14). This brief passage serves as a hinge, concluding the mission of the Twelve and preparing for the theme of nourishment and bread on which the next major section will focus.

6:31–32 Jesus recognizes that after their period of intense apostolic labors, the Twelve need to be refreshed once again in his presence and in their fellowship with one another. To “be with him” remains a requirement of fruitful apostleship that must be constantly renewed (3:14; see John 15:4). The deserted place recalls the desert of 1:3–13, a place of testing but also a place of solitude and retreat where God’s people withdraw from the world for special intimacy with him. Jesus’ desire to give them rest evokes the rest that God pledges to give his people in the promised land (Exod 33:14; Deut 12:10; see Heb 4:9–11). It also shows his concern for the practical, physical needs of those who spend themselves in his service.

From the fact that people were coming and going in great numbers it may be inferred that the apostles’ preaching of †repentance (6:12) had hit the mark. More people than ever were being drawn to Jesus and prepared to receive his teaching and his healing power. Once again Mark notes that the apostles’ ministry was so demanding that they had no opportunity even to eat (see 3:20). They are taking on the character of Jesus, who subordinates his personal needs to his ministry to his people. This remark prepares for the miracle of the loaves that is about to occur. Jesus and the apostles go off to a deserted place that, as we will soon see, turns out to be not so deserted after all.

Reflection and Application (6:30–32)

This brief passage illustrates the rhythm of Christian apostolic activity, which ought to alternate between periods of intense labor and periods of simply “being with” Jesus (see 3:14). Here we can imagine him taking time with each disciple to listen to the reports of their successes and failures, to encourage, counsel, and redirect them where necessary. What spiritual refreshment they must have found in this “debriefing” conversation. It is true that the demands of apostolic activity, both then and now, will occasionally preempt the need for physical and mental rest (see 6:33–34). But the temptation for those of us who work in Christ’s vineyard is to get so caught up in the busyness of ministry that we repeatedly ignore the need for prayer, rest, and stillness in God’s presence. When that happens it is all too easy to begin imperceptibly substituting our own agenda for the Lord’s. Authentic Christian ministry is rooted in prayer, since apart from him we can do nothing (John 15:1–8). How can we carry out the Lord’s work except in the Lord’s strength (see 1 Pet 4:11)? And how can we be renewed in that strength except by waiting in his presence (see Isa 40:31)?