The Lord Comes to His Temple

Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem marks the beginning of passion week, the final days of his life in which he will fulfill his destiny as suffering and glorified Messiah. Everything in the Gospel has been leading up to these climactic events, to which Mark devotes over a third of his narrative. It begins with Jesus’ entrance into the Holy City and the temple as her humble king. But how will Jerusalem receive her Messiah?

The King Enters His City (11:1–11)

1When they drew near to Jerusalem, to Bethphage and Bethany at the Mount of Olives, he sent two of his disciples 2and said to them, “Go into the village opposite you, and immediately on entering it, you will find a colt tethered on which no one has ever sat. Untie it and bring it here. 3If anyone should say to you, ‘Why are you doing this?’ reply, ‘The Master has need of it and will send it back here at once.’ ” 4So they went off and found a colt tethered at a gate outside on the street, and they untied it. 5Some of the bystanders said to them, “What are you doing, untying the colt?” 6They answered them just as Jesus had told them to, and they permitted them to do it. 7So they brought the colt to Jesus and put their cloaks over it. And he sat on it. 8Many people spread their cloaks on the road, and others spread leafy branches that they had cut from the fields. 9Those preceding him as well as those following kept crying out:

“Hosanna!

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!

10Blessed is the kingdom of our father David that is to come!

Hosanna in the highest!”

11He entered Jerusalem and went into the temple area. He looked around at everything and, since it was already late, went out to Bethany with the Twelve.

OT: 1 Kings 1:32–34; 1 Macc 13:51; Ps 118:25–26; Zech 9:9

NT: // Matt 21:1–11; Luke 19:28–40; John 12:12–16

Catechism: Jesus’ messianic entrance, 559–60

Lectionary: Palm Sunday Procession (Year B)

11:1–2 Jesus has come to the last stage of his journey, the resolute journey to the cross that began when he first announced his coming passion (8:27–31). Although he most likely visited Jerusalem many times in his life to celebrate the Jewish feasts (see Luke 2:22, 41; John 2:13; 5:1; 7:10), Mark mentions only this one visit: it is the Messiah-King’s entrance into the Holy City. Bethany and Bethphage were the last villages on the road from Jericho (Mark 10:46), located on the Mount of Olives just east of Jerusalem. Zechariah had prophesied that the Mount of Olives would be the site where God’s kingship over the whole earth would be revealed in the last days (Zech 14:4–9)—a prophecy that was about to be fulfilled, but in a hidden manner.

Jesus had refused popular acclaim as Messiah (Mark 8:30; see John 6:15), but now he takes the initiative in preparing for his messianic entry into the city. The elaborate preparations point to the deeply symbolic significance of what he is about to do. He sends two of his disciples to carry out the task, as he had sent them out in pairs previously (Mark 6:7) and will do again for the Passover meal (14:13). The village opposite is probably Bethphage, less than a mile from the city. There a colt (a young donkey) is tethered, on whom no one has ever sat—recalling Old Testament stipulations that an animal devoted to a sacred purpose must be one that has not been put to any ordinary use (Num 19:2; Deut 21:3; 1 Sam 6:7). The tethered colt evokes Gen 49:10–11, Jacob’s prophecy of a king to come from the tribe of Judah (see Matt 2:6), another clue to the messianic significance of Jesus’ action.

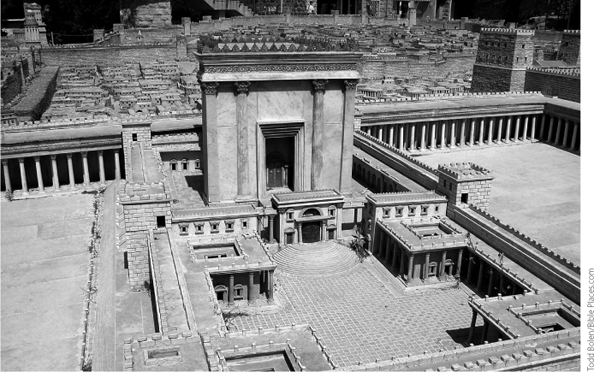

Fig. 9. Scale model of the Herodian temple.

Jerusalem, the Holy City

Jerusalem—“the city of our God; the holy mountain, fairest of heights, the joy of all the earth,… the city of the great king” (Ps 48:2–4)—was identified in Jewish tradition as the site of Mount Moriah, where Abraham had been willing to offer his son Isaac in sacrifice (Gen 22:2; 2 Chron 3:1), a prefigurement of the ultimate sacrifice of the Beloved Son (Rom 8:32). Jerusalem was also identified as the Salem of the mysterious priest-king Melchizedek, who offered bread and wine (Gen 14:18), foreshadowing the Eucharist.

King David conquered the city in about 1000 BC and chose it as his capital. One of the great moments in Israel’s history was when David brought the Ark of the Covenant into the city in procession, with music, sacrifices, and dancing for joy before the Lord (2 Sam 6:12–19). His son Solomon built the magnificent temple to house the Ark, and the Holy City became the center of religious life for the Israelites and the place of God’s special favor.

After the Jews’ exile and return from Babylon, the city and temple were rebuilt, but without attaining their former glory. Through the prophets God promised a new and glorious Jerusalem, a place of overflowing joy and center of worship for the entire world (see Isa 2:2–3; 60:1–22; Zeph 3:14–17; Hag 2:7–9).

At the time of Jesus, the temple had been renovated and Jerusalem was near the pinnacle of her earthly splendor. On each of the three great Jewish feasts—Passover, Weeks (Pentecost), and Booths—the city was flooded with pilgrims, more than tripling its normal population of about 40,000. Yet as Jesus’ words and prophetic gestures make clear, the Holy City was marred by corruption and religious hypocrisy. His warning of a great devastation (Mark 13:1–30) was tragically fulfilled when Jerusalem was leveled to the ground by Roman legions in AD 70.

11:3–6 Jesus instructs his disciples how to answer if anyone should challenge them. The word for Master is literally “the Lord” (ho Kyrios), the term used in the †Septuagint for the sacred name of God. It is the only time in Mark that Jesus explicitly refers to himself as the Lord, pointing to his divine identity, though he does so implicitly at times.[1] The disciples find things just as he had said (see 14:16). Jesus’ precise instructions and foreknowledge of what would happen seem to indicate that he had made some prearrangements with the colt’s owner. The implication is that he has faithful followers in many places, who consider themselves and their possessions to be wholly at his disposal. On a symbolic level he is exercising the kingly right to requisition an animal for his service. But more importantly, these details serve as a reminder that Jesus is fully aware of the destiny that will meet him in Jerusalem, and that every detail takes place according to the plan of God (see Acts 2:23).

11:7 Why did Jesus choose to ride a colt, when most pilgrims would enter the city on foot? It was a prophetic gesture, fulfilling the messianic prophecy of Zechariah: “Rejoice heartily, O daughter Zion, shout for joy, O daughter Jerusalem! See, your king shall come to you; a just savior is he, meek, and riding on an ass, on a colt, the foal of an ass” (Zech 9:9). The lowly animal shows that he, the King of glory (see Ps 24:7–10), comes in humility and peace, not as a warrior-king mounted on a stallion to lead a rebellion against Rome. It is also reminiscent of the royal procession of Solomon, the son of David, who rode a mule into the city at his coronation (1 Kings 1:32–34). Jesus knew what he was about, even if those around him did not yet realize its significance.

11:8–9 Jesus’ triumphal entry takes place among thousands of pilgrims arriving in the Holy City for the feast of Passover (14:1). There is a sense of excitement and elation, as the crowd around him shouts for joy and spontaneously shows him signs of honor. To spread cloaks on the road was a gesture of homage before a newly crowned king (see 2 Kings 9:13). Mark’s description evokes an occasion some two centuries earlier, when Simon Maccabeus and his followers entered the city after their successful revolt “with shouts of jubilation, waving of palm branches … and the singing of hymns and canticles, because a great enemy of Israel had been destroyed” (1 Macc 13:51). The crowd chants from Ps 118:25–26: Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! This psalm, originally a royal song of thanksgiving for a military victory, was one of the great hymns sung by pilgrims processing into the temple for a festival. Jesus will later apply it specifically to his coming passion and resurrection (Mark 12:10–11). Hosanna is a Hebrew word that originally meant “Save us!” but in liturgical usage had become a shout of praise or acclamation, much like “Hallelujah!” The blessing on “he who comes in the name of the Lord” was a customary greeting, but also has a deeper significance: Jesus comes in God’s name as his faithful representative, who will perfectly accomplish his will.

Biblical Acclamations in the Liturgy

The acclamations with which the crowds greeted Jesus are among the many biblical phrases that have become part of the eucharistic liturgy. “Hosanna in the highest!” and “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!” are joined with the angelic chorus, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God almighty” (Rev 4:8; see Isa 6:3) as the people’s acclamation introducing the eucharistic prayer. These phrases are now understood in their fullest meaning: God’s people jubilantly welcome our Messiah-King, Jesus, who is truly present on the altar, and who comes in the name of the Lord to save us and establish God’s kingdom.

11:10 The cry, Blessed is the kingdom of our father David that is to come! expresses messianic hope, but without directly acknowledging Jesus as Messiah. The people’s enthusiasm is genuine, but they do not seem to recognize that the time of fulfillment has already arrived (1:15), and that the kingdom has come in the person of Jesus himself, the “son of David” (10:47). Nor do they realize that his kingship will be exercised not in a political restoration of the Davidic monarchy, but on the cross.

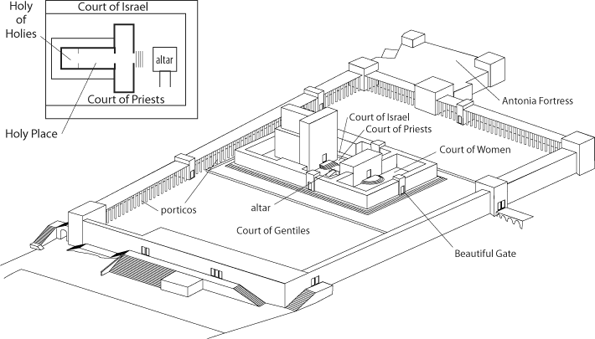

Fig. 10. Diagram of the Herodian Temple

The Temple

For the Jews, the holiest place on earth, where God had chosen to make his dwelling, was the Jerusalem temple. Solomon constructed the magnificent edifice with quarried stones and cedars brought by ship from Lebanon (1 Kings 6), completing it in about 950 BC, and it stood as the center of Jewish worship until it was destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 BC. It was soon rebuilt, and just before the birth of Jesus, King Herod the Great began a grandiose temple renovation project. He decorated the sanctuary’s white marble façade with gold that gleamed in the sun, and expanded the platform on which the building stood to a massive thirty-five acres. This was the temple Jesus knew.

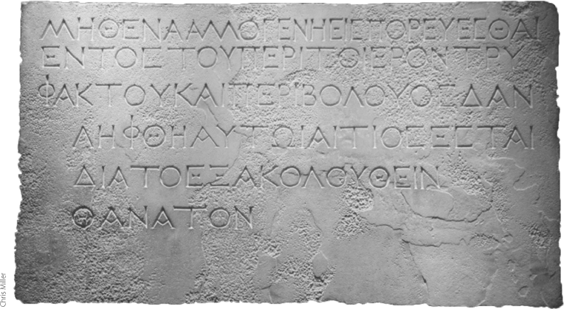

Temple worship took place in the open air. Only priests entered the sanctuary itself, which was relatively small. Within the sanctuary was the Holy Place, where incense was offered, and the inner chamber set off by a curtain, the Holy of Holies. The sanctuary was surrounded by a series of outdoor courts, each with strict rules of access. Immediately in front of it was the Court of Priests, accessible only to priests and Levites, in which stood the great altar of sacrifice. Smoke from the daily burning sacrifices was visible for miles around. Beyond it was the Court of Israel, which only ritually pure Jewish men could enter. Next was the Court of Women; prominent inscriptions warned Gentiles not to enter on pain of death. Finally, the largest part of the temple plaza was the Court of Gentiles, a vast rectangular area enclosed with stately colonnades, interspersed with nine gates. Typically it was crowded with Jews and Gentile converts to Judaism from all over Palestine and the Roman Empire. At the time of Jesus it was also full of merchants, animal stalls, and currency exchanges.

11:11 The royal entrance that began so exuberantly ends on a quieter note. The crowd seems to have dispersed by the time Jesus enters the temple area. He comes as the Lord of the temple, who looks around the holy dwelling with his searching gaze to see whether its true purposes are being fulfilled. The prophet Malachi had foretold such a coming of the Lord, marked by a purifying judgment: “And suddenly there will come to the temple the LORD whom you seek.… But who will endure the day of his coming? And who can stand when he appears? For he is like the refiner’s fire” (Mal 3:1–2).

Since it is late in the day, Jesus and the Twelve leave the city and return to their lodgings (or campsite) in Bethany.

The Fruitless Fig Tree (11:12–14)

12The next day as they were leaving Bethany he was hungry. 13Seeing from a distance a fig tree in leaf, he went over to see if he could find anything on it. When he reached it he found nothing but leaves; it was not the time for figs. 14And he said to it in reply, “May no one ever eat of your fruit again!” And his disciples heard it.

OT: Hosea 9:10; Mic 7:1

NT: Luke 13:6–9. // Matt 21:18–19

The episode of the fig tree (vv. 11–14 and 20–26) at first seems very perplexing. Is Jesus’ reaction to the tree simply an outburst of temper? Like his triumphal entry on the previous day, both the fig tree incident and the cleansing of the temple inserted in the middle of it (vv. 15–19) are real-life parables, symbolic actions that must be pondered to discover their hidden meaning.

11:12–14 Jesus and his disciples leave their lodgings in Bethany to enter the Holy City once again. It is the only occasion in Mark where Jesus is said to be hungry. Seeing a fig tree in leaf, he walks over to see if it could satisfy his hunger—only to find it fruitless. But there is something odd about this action, to which Mark alerts us by noting that it was not the time for figs. It is the time of Passover, in April, and Jesus, like any native of Palestine, would know that ripe figs do not appear until June. Why, then, is he looking for fruit? The meaning of his action comes to light only when considered against the Old Testament background. In the prophets, Israel is often symbolized by figs or a fig tree (Jer 24:1–8; 29:17; Hosea 9:10; Joel 1:7). Jesus’ search for ripe figs recalls God’s desire to find in Israel the fruit of righteousness and covenant fidelity, and his grief at not finding it: “Alas! … There is no cluster to eat, no early fig that I crave” (Mic 7:1). The withering of a fig tree is a symbol of God’s judgment against Israel and the temple for the idolatry and injustices perpetrated there (Joel 1:7–12; see Jer 8:13; Hosea 2:14). Moreover, in Mark, fruitfulness is an image for responding to Jesus in faith (see Mark 4:1–20; 12:1–12). The tree’s lack of fruit thus signifies the absence of faith and prayer that Jesus finds in the temple (11:17–18). Now, at the time of visitation by her Messiah and Lord (Luke 19:44), the temple and its leadership are devoid of the spiritual fruit that God desires. Jesus’ pronouncement upon the tree, May no one ever eat of your fruit again! is a prophetic signal that Israel’s temple worship and sacrifices, with all their earthly splendor, are drawing to an end. That his disciples heard Jesus’ saying prepares us for the resumption of the story in 11:20.

The Cleansing of the Temple (11:15–19)

15They came to Jerusalem, and on entering the temple area he began to drive out those selling and buying there. He overturned the tables of the money changers and the seats of those who were selling doves. 16He did not permit anyone to carry anything through the temple area. 17Then he taught them saying, “Is it not written:

‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples’?

But you have made it a den of thieves.”

18The chief priests and the scribes came to hear of it and were seeking a way to put him to death, yet they feared him because the whole crowd was astonished at his teaching. 19When evening came, they went out of the city.

OT: Ps 69:10; Jer 7:1–15; Zech 14:21

NT: // Matt 21:12–17; Luke 19:45–48; John 2:13–17

Catechism: Jesus and the temple, 583–86; the temple, 2580

11:15–16 On the previous evening, Jesus had “looked around at everything” in the temple (v. 11) as if to assess its spiritual condition. Now he takes vehement action against the commercialism and rank corruption he has found. Commercial activity connected with the temple was necessary, since pilgrims had to purchase the unblemished animals or birds that they would offer in sacrifice. A lamb or goat brought from the flock at home, perhaps hundreds of miles away, would not necessarily be in shape to pass inspection by the time it arrived in the city. There were several markets for sacrificial animals on the Mount of Olives. But the temple authorities had also allowed trading within the temple precincts, in the vast Court of the Gentiles. Since all adult Jewish men had to pay an annual temple tax (see Matt 17:24), money changers had also been conveniently set up to exchange pilgrims’ Greek or Roman coins for the shekels in which the tax had to be paid. Other merchants were selling doves, required for ritual purifications of women after childbirth or of those healed of disease who could not afford lambs (Lev 12:8; 14:21–22; Luke 2:22–24). The temple area had become a marketplace, a noisy hubbub of business. Instead of the temple sanctifying the city, the city was profaning the temple.

Jesus is appalled at this flagrant desecration of a place consecrated to the worship of the living God. His actions bespeak burning indignation and zeal for the holiness of God’s house (see John 2:17; Ps 69:10). He overturns the tables and seats of the merchants, putting a halt to the trading activity. Moreover, he forbids people to carry anything (literally, “any vessel”) through the temple area, as if they could use the sacred precincts as a thoroughfare.[2] One can imagine the stunned surprise of those whose trade has been disrupted. For anyone paying attention, Jesus’ actions signal the arrival of “that day” prophesied by Zechariah, when the Lord would gather all nations to worship him in Jerusalem, and “there shall no longer be any merchant in the house of the LORD of hosts” (Zech 14:21). Moreover, Jesus is exercising a royal prerogative: the reformer kings of Judah, Hezekiah and Josiah, had “cleaned house” in the temple in their own day (2 Chron 29; 34).

11:17 Jesus explains the meaning of this prophetic gesture—his third since arriving at Jerusalem—by quoting two scriptures, first from Isaiah: My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples. Only Mark includes “for all peoples” (that is, for all Gentiles),[3] a phrase that would have special meaning for his mostly Gentile readers. In the context of this scripture God had promised to bring the Gentiles “to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer” (Isa 56:6–7 RSV). The temple was to be a place of reverence and awe before the Lord, the air filled with psalms of praise or teaching on God’s word (Neh 8:1–8; Ps 27:4; 48:10; 100:4). But the market activity had effectively prevented the temple courts from being a place of prayer where Gentiles could enter into God’s presence. Israel was faltering in its mission to lead the whole world in the worship of †YHWH (see Ps 105:1; Isa 2:2–3; Jer 3:17), a mission that would, however, paradoxically be fulfilled through the death of Israel’s Messiah (see Mark 15:39).

Jesus continues with a quote from Jeremiah: But you have made it a den of thieves. Jeremiah had denounced those who thought they could get away with greed and dishonesty by taking refuge in ceremonial piety (Jer 7:9–11). The prophet warned that just as God had allowed his earlier shrine at Shiloh to be destroyed, so he would do with the temple in Jerusalem unless his people mended their ways. Jeremiah’s dire warning came to pass in 587 BC, and a replay of that calamity would occur within forty years of Jesus’ words.

11:18–19 Jesus’ actions may have affected only a portion of the vast temple courts, but their symbolic import as a challenge to the temple authorities—and a threat to their lucrative sources of income—did not go unnoticed. The temple authorities controlled all commerce, donations, and taxes connected with the temple, enriching themselves with the profits. Archaeological excavations near the temple mount have uncovered the remains of palatial mansions that belonged to the ruling priestly families. It is no surprise that, hearing of what Jesus had done, the authorities were seeking a way to put him to death. For now they do nothing for fear of popular reprisals. Mark does not tell us the content of Jesus’ teaching, but perhaps it was about the holiness of God’s house and the new temple “not made with hands” that he was about to establish (see 14:58).

Reflection and Application (11:15–19)

Jesus’ gesture of disrupting the temple commerce is a prophetic warning of the far greater disruption that he foretells (13:2). As the following episode will show, it also prepares the way for understanding the new and greater temple of the new covenant, the temple “not made with hands” (14:58) that is his own body (John 2:21; Heb 9:11). Thus Jesus’ cleansing of the temple also has significance for the Church, the body of Christ. Christians today can ask: Are we consumed with the zeal for God’s house that motivated Jesus (John 2:17)? If we consider the “temple” of our own parish or community, do we find it polluted with what does not belong there—with self-serving leadership, factions, gossip, sexual immorality, commercialization, or lack of charity toward those outside one’s socioethnic group? Are we bringing the Church into the world, or the world into the Church? Surely the stewards of the ancient temple are not the only ones guilty of compromising the holiness of God’s house. The book of Revelation (2–3) depicts Christ coming to judge local churches, threatening to remove the lampstand of those that do not repent and bear good fruit. The point is not for us to judge others—which would only compound the problem—but to repent for our own part, “to weep and mourn” (Joel 1:13–14), interceding that God’s living temple would be restored to holiness.

On another level, St. Paul affirms that not only the Church but also our individual bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor 6:19–20). If we consider our own heart, is it sometimes more like a marketplace than a temple? Is it cluttered with worldly pursuits, busyness, lust, or selfish preoccupations? If so, we can pray that Jesus would cleanse this temple too and make it a house of prayer.

The Withered Fig Tree (11:20–26)

20Early in the morning, as they were walking along, they saw the fig tree withered to its roots. 21Peter remembered and said to him, “Rabbi, look! The fig tree that you cursed has withered.” 22Jesus said to them in reply, “Have faith in God. 23Amen, I say to you, whoever says to this mountain, ‘Be lifted up and thrown into the sea,’ and does not doubt in his heart but believes that what he says will happen, it shall be done for him. 24Therefore I tell you, all that you ask for in prayer, believe that you will receive it and it shall be yours. 25When you stand to pray, forgive anyone against whom you have a grievance, so that your heavenly Father may in turn forgive you your transgressions.” [26]

OT: Ezek 17:24; Hosea 2:14; Joel 1:7–12

NT: Matt 6:14–15; 17:20; Luke 17:5–6; 1 John 5:14–15. // Matt 21:20–22

Catechism: boldness in prayer, 2609–11, 2734–41; forgiveness, 2842–45

Mark helps us understand the withering of the fig tree in light of the cleansing of the temple by weaving together the two incidents. Jesus’ pronouncement on the tree symbolizes God’s judgment on the temple and its stewards for their spiritual barrenness, a barrenness that consists fundamentally in their refusal to heed Jesus, the Lord of the temple. Like the tree, the temple will come to an end: “There will not be one stone left upon another” (13:2).

11:20–21 Noticing the fig tree withered to its roots, Peter marvels at the effect of Jesus’ pronouncement the previous day (v. 14). The tree is not only fruitless, but completely dead. Another, more fruitful tree must take its place. Perhaps in the background is Ezekiel’s vision of the new temple, from which flowed a river with trees along its banks, bearing fruit all year round (Ezek 47:1–12; see Mark 11:13).

The early Church came to understand the cross on which Christ died as the tree of life (see Gen 2:9), bearing the fruit of conversion and holiness all year long (see Ezek 47:1–12; 1 Pet 2:24; Rev 22:2). A troparion (antiphon) sung in Orthodox churches on Holy Cross Sunday proclaims: “Today the ranks of angels dance with gladness at the veneration of Thy Cross. For through the Cross, Christ, Thou hast shattered the hosts of devils and saved mankind. The Church has been revealed as a second Paradise, having within it, like the first Paradise of old, a tree of life, Thy Cross, O Lord. By touching it we share in immortality.”[a]

11:22 Jesus responds with a call to faith, followed by a short teaching on faith, prayer, and forgiveness. Faith is the right human response to God’s faithfulness: a complete trust and reliance on him, including the confident expectation that he will hear and respond to our prayers.[4] Without it, prayers are empty words. The disciples must trust that their prayers will be heard and that their prophetic utterances, like that of Jesus, will actually be carried out. The context suggests that Jesus is also encouraging the disciples, who are undoubtedly shaken by his prophetic judgment of the temple and the omen of the withered fig tree, not to lose confidence in God’s sovereignty over events. God has the solution to the tragedy of the barren temple, symbolized by the withered tree. He can even “make the withered tree bloom” (Ezek 17:24).

11:23 Jesus continues with a solemn promise, found in different contexts in Matthew (17:20) and Luke (17:6). This mountain could refer to the Mount of Olives or, more likely, to the temple mount that looms before them as they walk into the city. The Old Testament often has the image of mountains being leveled to make way for the establishment of God’s reign (Isa 40:4; Bar 5:7; Zech 14:10). What could be more impossible than a mountain being lifted up and thrown into the sea? But Jesus has already assured his disciples that “all things are possible for God” (10:27). The image of a mountain moving is not an invitation to test God by asking for spectacular phenomena (see 8:12). Rather, it expresses the limitless power of prayer rooted in unconditional faith: before it all obstacles to God’s plan are removed, even the seemingly impossible.

11:24 The third saying puts the same principle in more general terms. The mention of prayer recalls Jesus’ earlier words about the temple being a “house of prayer” (11:17) and thus hints that the replacement for the defunct temple will be the community of disciples gathered around Jesus in faith and prayer.[5] Jesus’ “house,” the Church, is the new house of prayer for all peoples (see John 4:21, 23). Jesus’ disciples are to pray with the utter confidence of children who know their Father hears even before they ask (see Isa 65:24; Matt 6:8; 1 John 3:22; 5:14–15). The Greek reads literally, “believe that you have received it.”

11:25 Finally, Jesus mentions a condition for efficacious prayer, the same recorded in Matthew after the Our Father (Matt 6:14).[6] Standing was the primary traditional posture of prayer for Jews and Christians (1 Kings 8:22; Ps 134:1). Jesus had earlier spoken of God as his own Father (Mark 8:38), but now he includes his disciples in that filial relationship. The basis for our confidence in God in prayer is that he is our loving Father, who cares for all our needs and listens to us as to his own beloved children. But unforgiveness is an obstacle that blocks us both from receiving God’s forgiveness and from drawing near to him in prayer. By the hidden laws of the spiritual life, we are not able to open ourselves to God’s boundless mercy unless we release others from their infinitely smaller debts to us, as the parable of the unmerciful servant illustrates (Matt 18:21–35).

Reflection and Application (11:20–26)

These words on faith and prayer present a challenge to every believer. Did Jesus really mean what he said? If so, why have our fervent prayers sometimes apparently gone unanswered? The answer lies in understanding “believe” in the biblical sense in which Jesus used it. To believe is not to work up a subjective feeling of certitude that our prayers will be answered. Rather, it is to enter into a personal, trusting relationship with God so that our prayers become aligned with the true good that he desires for us. Elsewhere this promise includes the qualification that our prayers must be in Jesus’ name (John 14:13) or “according to his will” (1 John 5:14), and not with a divided heart (James 4:3–5). Jesus himself is the model for prayer that is always answered because of his total surrender to the Father’s will (see John 8:29; 11:42). The more we are united with him the more his desires and priorities become our own, and the more we will see how God answers them. This is the kind of faith Jesus is referring to, not a “faith” that views God as a kind of cosmic vending machine ready to carry out our every request. “Do not be troubled if you do not immediately receive from God what you ask him; for he desires to do something even greater for you, while you cling to him in prayer.”[7]