ONE

Tucker

A mouse was looking at Mario.

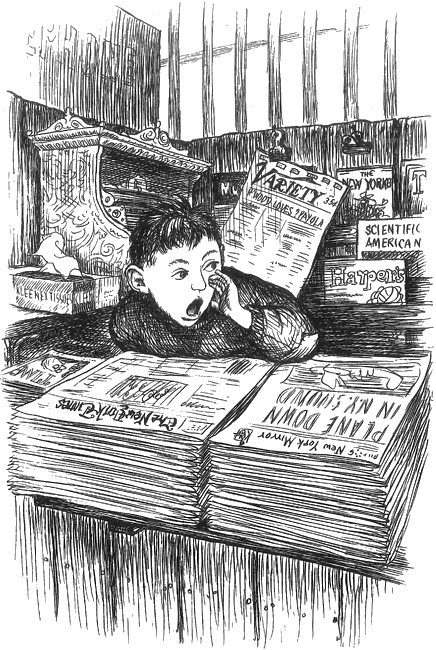

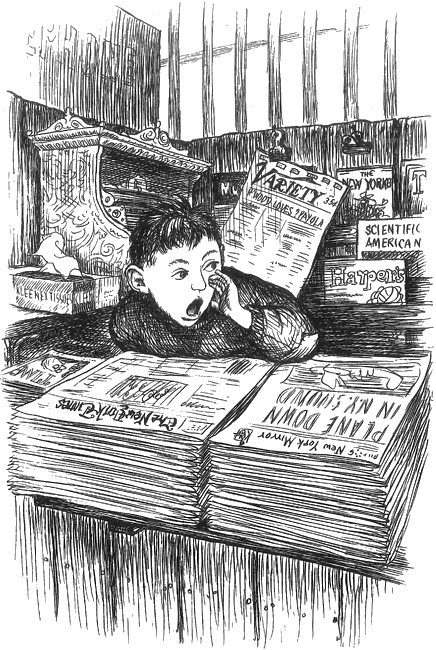

The mouse’s name was Tucker, and he was sitting in the opening of an abandoned drain pipe in the subway station at Times Square. The drain pipe was his home. Back a few feet in the wall, it opened out into a pocket that Tucker had filled with the bits of paper and shreds of cloth he collected. And when he wasn’t collecting, “scrounging” as he called it, or sleeping, he liked to sit at the opening of the drain pipe and watch the world go by—at least as much of the world as hurried through the Times Square subway station.

Tucker finished the last few crumbs of a cookie he was eating—a Lorna Doone shortbread he had found earlier in the evening—and licked off his whiskers. “Such a pity,” he sighed.

Every Saturday night now for almost a year he had watched Mario tending his father’s newsstand. On weekdays, of course, the boy had to get to bed early, but over the weekends Papa Bellini let him take his part in helping out with the family business. Far into the night Mario waited. Papa hoped that by staying open as late as possible his newsstand might get some of the business that would otherwise have gone to the larger stands. But there wasn’t much business tonight.

“The poor kid might as well go home,” murmured Tucker Mouse to himself. He looked around the station.

The bustle of the day had long since subsided, and even the nighttime crowds, returning from the theaters and movies, had vanished. Now and then a person or two would come down one of the many stairs that led from the street and dart through the station. But at this hour everyone was in a hurry to get to bed. On the lower level the trains were running much less often. There would be a long stretch of silence; then the mounting roar as a string of cars approached Times Square; then a pause while it let off old passengers and took on new ones; and finally the rush of sound as it disappeared up the dark tunnel. And the hush fell again. There was an emptiness in the air. The whole station seemed to be waiting for the crowds of people it needed.

Tucker Mouse looked back at Mario. He was sitting on a three-legged stool behind the counter of the newsstand. In front of him all the magazines and newspapers were displayed as neatly as he knew how to make them. Papa Bellini had made the newsstand himself many years ago. The space inside was big enough for Mario, but Mama and Papa were cramped when they each took their turn. A shelf ran along one side, and on it were a little secondhand radio, a box of Kleenex (for Mama’s hay fever), a box of kitchen matches (for lighting Papa’s pipe), a cash register (for money—which there wasn’t much of), and an alarm clock (for no good reason at all). The cash register had one drawer, which was always open. It had gotten stuck once, with all the money the Bellinis had in the world inside it, so Papa decided it would be safer never to shut it again. When the stand was closed for the night, the money that was left there to start off the new day was perfectly safe, because Papa had also made a big wooden cover, with a lock, that fitted over the whole thing.

Mario had been listening to the radio. He switched it off. Way down the tracks he could see the lights of the shuttle train coming toward him. On the level of the station where the newsstand was, the only tracks were the ones on which the shuttle ran. That was a short train that went back and forth from Times Square to Grand Central, taking people from the subways on the west side of New York City over to the lines on the east. Mario knew most of the conductors on the shuttle. They all liked him and came over to talk between trips.

The train screeched to a stop beside the newsstand, blowing a gust of hot air in front of it. Only nine or ten people got out. Tucker watched anxiously to see if any of them stopped to buy a paper.

“All late papers!” shouted Mario as they hurried by. “Magazines!”

No one stopped. Hardly anyone even looked at him. Mario sank back on his stool. All evening long he had sold only fifteen papers and four magazines. In the drain pipe Tucker Mouse, who had been keeping count too, sighed and scratched his ear.

Mario’s friend Paul, a conductor on the shuttle, came over to the stand. “Any luck?” he asked.

“No,” said Mario. “Maybe on the next train.”

“There’s going to be less and less until morning,” said Paul.

Mario rested his chin on the palm of his hand. “I can’t understand it,” he said. “It’s Saturday night too. Even the Sunday papers aren’t going.”

Paul leaned up against the newsstand. “You’re up awfully late tonight,” he said.

“Well, I can sleep on Sundays,” said Mario. “Besides, school’s out now. Mama and Papa are picking me up on the way home. They went to visit some friends. Saturday’s the only chance they have.”

Over a loudspeaker came a voice saying, “Next train for Grand Central, track 2.”

“’Night, Mario,” Paul said. He started off toward the shuttle. Then he stopped, reached in his pocket, and flipped a half dollar over the counter. Mario caught the big coin. “I’ll take a Sunday Times,” Paul said, and picked up the newspaper.

“Hey wait!” Mario called after him. “It’s only twenty-five cents. You’ve got a quarter coming.”

But Paul was already in the car. The door slid closed. He smiled and waved through the window. With a lurch the train moved off, its lights glimmering away through the darkness.

Tucker Mouse smiled too. He liked Paul. In fact he liked anybody who was nice to Mario. But it was late now: time to crawl back to his comfortable niche in the wall and go to sleep. Even a mouse who lives in the subway station in Times Square has to sleep sometimes. And Tucker had a big day planned for tomorrow, collecting things for his home and snapping up bits of food that fell from the lunch counters all over the station. He was just about to turn into the drain pipe when he heard a very strange sound.

Now Tucker Mouse had heard almost all the sounds that can be heard in New York City. He had heard the rumble of subway trains and the shriek their iron wheels make when they go around a corner. From above, through the iron grilles that open onto the streets, he had heard the thrumming of the rubber tires of automobiles, and the hooting of their horns, and the howling of their brakes. And he had heard the babble of voices when the station was full of human beings, and the barking of the dogs that some of them had on leashes. Birds, the pigeons of New York, and cats, and even the high purring of airplanes above the city Tucker had heard. But in all his days, and on all his journeys through the greatest city in the world, Tucker had never heard a sound quite like this one.