TWELVE

Mr. Smedley

It was two o’clock in the morning. Chester Cricket’s new manager, Tucker Mouse, was pacing up and down in front of the cricket cage. Harry Cat was lying on the shelf with his tail drooping over the edge, and Chester himself was relaxing in the matchbox.

“I have been giving the new situation my serious consideration,” said Tucker Mouse solemnly. “As a matter of fact, I couldn’t think of anything else all day. The first thing to understand is: Chester Cricket is a very talented person.”

“Hear! hear!” said Harry. Chester smiled at him. He was really an awfully nice person, Harry Cat was.

“The second thing is: talent is something rare and beautiful and precious, and it must not be allowed to go to waste.” Tucker cleared his throat. “And the third thing is: there might be—who could tell?—a little money in it, maybe.”

“I knew that was at the bottom of it,” said Harry.

“Now wait, please, Harry, please, just listen a minute before you begin calling me a greedy rodent,” said Tucker. He sat down beside Chester and Harry. “The newsstand is doing lousy business—right? Right! If the Bellinis were happy, Mama Bellini wouldn’t be always wanting to get rid of him—right? Right! She likes him today because he played her favorite songs, but who can tell how she might like him tomorrow?”

“And also I’d like to help them because they’ve been so good to me,” put in Chester Cricket.

“But naturally!” said Tucker. “And if a little bit of the rewards of success should find its way into a drain pipe where lives an old and trusted friend of Chester—well, who is the worse for that?”

“I still don’t see how we can make any money,” said Chester.

“I haven’t worked out the details,” said Tucker. “But this I can tell you: New York is a place where the people are willing to pay for talent. So what’s clear is, Chester has got to learn more music. I personally prefer his own compositions—no offense, Chester.”

“Oh no,” said the cricket. “I do myself.”

“But the human beings,” Tucker went on, “being what human beings are—and who can blame them?—would rather hear pieces written by themselves.”

“But how am I going to learn new songs?” asked Chester.

“Easy as pie,” said Tucker Mouse. He darted over to the radio, leaned all his weight on one of the dials, and snapped it on.

“Not too loud,” said Harry Cat. “The people outside will get suspicious.”

Tucker twisted the dial until a steady, soft stream of music was coming out. “Just play it by ear,” he said to Chester.

That was the beginning of Chester’s formal musical education. On the night of the party he had just been playing for fun, but now he seriously set out to learn some human music. Before the night was over he had memorized three movements from different symphonies, half a dozen songs from musical comedies, the solo part for a violin concerto, and four hymns—which he picked up from a late religious service.

* * *

The next morning, which was the last Sunday in August, all three Bellinis came to open the newsstand. They could hardly believe what had happened yesterday and were anxious to see if Chester would continue to sing familiar songs. Mario gave the cricket his usual breakfast of mulberry leaves and water, which Chester took his time eating. He could see that everyone was very nervous and he sort of enjoyed making them wait. When breakfast was over, he had a good stretch and limbered his wings.

Since it was Sunday, Chester thought it would be nice to start with a hymn, so he chose to open his concert with “Rock of Ages.” At the sound of the first notes, the faces of Mama and Papa and Mario broke into smiles. They looked at each other and their eyes told how happy they were, but they didn’t dare to speak a word.

During the pause after Chester had finished “Rock of Ages,” Mr. Smedley came up to the newsstand to buy his monthly copy of Musical America. His umbrella, neatly folded, was hanging over his arm as usual.

“Hey, Mr. Smedley—my cricket plays hymns!” Mario blurted out even before the music teacher had a chance to say good morning.

“And opera!” said Papa.

“And Italian songs!” said Mama.

“Well, well, well,” said Mr. Smedley, who didn’t believe a word, of course. “I see we’ve all become very fond of our cricket. But aren’t we letting our imagination run away with us a bit?”

“Oh no,” said Mario. “Just listen. He’ll do it again.”

Chester took a sip of water and was ready to play some more. This time, however, instead of “Rock of Ages,” he launched into a stirring performance of “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

Mr. Smedley’s eyes popped. His mouth hung open and the color drained from his face.

“Do you want to sit down, Mr. Smedley?” asked Papa. “You look a little pale.”

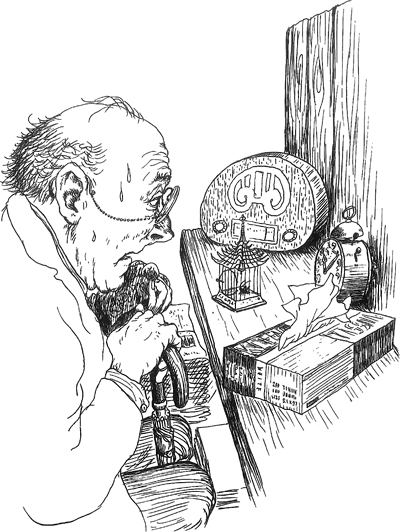

“I think perhaps I’d better,” said Mr. Smedley, wiping his forehead with a silk handkerchief. “It’s rather a shock, you know.” He came inside the newsstand and sat on the stool so his face was just a few inches away from the cricket cage. Chester chirped the second verse of “Onward Christian Soldiers,” and finished with a soaring “Amen.”

“Why, the organist played that in church this morning,” exclaimed the music teacher breathlessly, “and it didn’t sound half as good! Of course the cricket isn’t as loud as an organ—but what he lacks in volume, he makes up for in sweetness.”

“That was nothing,” said Papa Bellini proudly. “You should hear him play Aida.”

“May I try an experiment?” asked Mr. Smedley.

All the Bellinis said “yes” at once. The music teacher whistled the scale—do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, do. Chester flexed his legs, and as quickly as you could run your fingers up the strings of a harp, he had played the whole scale.

Mr. Smedley took off his glasses. His eyes were moist. “He has absolute pitch,” he said in a shaky voice. “I have met only one other person who did. She was a soprano named Arabella Hefflefinger.”

Chester started to play again. He went through the two other hymns he’d learned—“The Rosary” and “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”—and then did the violin concerto. Naturally, he couldn’t play it just as it was written without a whole orchestra to back him up, but he was magnificent, all things considered.

Once Mr. Smedley got used to the idea that he was listening to a concert given by a cricket, he enjoyed the performance very much. He had special praise for Chester’s “phrasing,” by which he meant the neat way the cricket played all the notes of a passage without letting them slide together. And sometimes, when he had been deeply moved by a section, the music teacher would touch his chest over his heart and say, “That cricket has it here!”

As Chester chirped his way through the program, a crowd collected around the newsstand. After each new piece, the people applauded and congratulated the Bellinis on their remarkable cricket. Mama and Papa were fit to burst with pride. Mario was very happy too, but of course he had thought all summer that Chester was a very unusual person.

When the playing was over, Mr. Smedley stood up and shook hands with Papa, Mama, and Mario. “I want to thank you for the most delightful hour I have ever spent,” he said. “The whole world should know of this cricket.” A light suddenly spread over his face. “Why, I believe I shall write a letter to the music editor of The New York Times,” he said. “They’d certainly be interested.”

And this is the letter Mr. Smedley wrote:

To the Music Editor of The New York Times and to the People of New York—

Rejoice, Oh New Yorkers—for a musical miracle has come to pass in our city! This very day, Sunday, August 28th, surely a day which will go down in musical history, it was my pleasure and privilege to be present at the most beautiful recital ever heard in a lifetime devoted to the sublime art. (Music, that is.) Being a musicologist myself, and having graduated—with honors—from a well-known local school of music, I feel I am qualified to judge such matters, and I say, without hesitation, that never have such strains been heard in New York before!

“But who was the artist?” the eager music lover will ask. “Was it perchance some new singer, just lately arrived from a triumphant tour of the capitals of Europe?”

No, music lovers, it was not!

“Then was it some violinist, who pressed his cheek with love against his darling violin as he played?”

Wrong again, music lovers.

“Could it have been a pianist—with sensitive, long fingers that drew magic sounds from the shining ivory keys?”

Ah, music lovers, you will never guess. It was a cricket! A simple cricket, no longer than half my little finger—which is rather long because I play the piano—but a cricket that is able to chirp operatic, symphonic, and popular music. Am I wrong, then, in describing such an event as a miracle?

And where is this extraordinary performer? Not in Carnegie Hall, music lovers—nor in the Metropolitan Opera House. You will find him in the newsstand run by the Bellini family in the subway station at Times Square. I urge—I implore!—every man, woman, and child who has music in his soul not to miss one of his illustrious—nay, his glorious—concerts!

Enchantedly yours,

Horatio P. Smedley

P.S. I also give piano lessons. For information write to:

H. P. Smedley

1578 West 63rd Street

New York, N.Y.