Postscript

One evening, after they had joined the Colvilles for dinner, and had walked back down the lane that separated the house from the cottage they’d been given at a peppercorn rent, Ilia had gone upstairs to the bathroom to get undressed for bed, and found she was missing her rings. She was in the habit of taking them off for the night and leaving them in a porcelain dish by the basin, but they were no longer on her finger. She looked again; she could not believe they were missing.

In the bathroom, stuck fast to the floor, she stood whimpering until Esmond called out to her, ‘Anything the matter, baby?’

When nothing happened, he coaxed, ‘I think I’ll need to wash too quite soon.’

She slipped the bolt and faced him, trembling.

‘I knew I should have had them adjusted!’ she cried.

The summer night had been cool when they came home and her finger was slender. She shouldn’t have risked wearing them outside, but they made her feel, when in the company of people like the Colvilles in their own house on their own land, able to play her part as Mrs Warner.

She was in despair; she wanted to go out again into the night, retrace their steps along the way that very minute in the dark, search the hedgerows with Esmond’s field torch, call on their friends regardless of the hour, beseech them to look around where the rings might have slipped off her finger.

‘When you took off your gloves,’ he said. ‘Look inside them.’

He didn’t seem very perturbed. Not like her.

‘But I would have noticed,’ she wailed, ‘if I hadn’t had them during the meal, I know I would have noticed.’

She was pleading to hunt for them, but Esmond was too tired, he said, and he had to be up early to get to London. Besides, they’d see next to nothing even with the torch.

‘Don’t worry baby – they’ll turn up. Somebody will see ’em, that’s the virtue of sparkling.’

She was incredulous at his equanimity. ‘But …’ she began.

She was crying at her folly. How idiotic and vain of her to wear diamonds to go out in the country lanes. Joan Colville, even though she was formally a Lady, never wore anything like that – her shirts were frayed, and the cat had pulled threads in her cardigans, and there were dog hairs everywhere on her clothes and the furniture and carpets. She was always commenting on Ilia’s elegance, and anyway, diamonds didn’t really go with the new walking shoes Esmond had had made for her or with her new hacking jacket of good tweed, the cloth that gives meaning to the phrase dyed-in-the-wool, which he had also bought her for life in England; incongruous and foolish, too, for the rings were gone.

The loss was a dreadful omen. The diamonds were the warrant of her escape into a new security, a kind of passport worn in full sight, a proof of new identity, family, position and value. And they had been his mother’s; that counted as a token of entry, to be shown at doors that would previously have been closed. The wedding band, the sapphire engagement ring – they were pledges of Esmond’s love and their union. But the diamonds, which were so large, so many, and which had caused such surprise and joy among her family at the sudden leap of her prospects, they were gone.

Her entire life, till her arrival in England, had known little else but scarcity and graft. Those years of government by the henchmen the Duce appointed to sustain the regime in the south, brought a daily struggle to elude official embezzlers and pilferers, to watch out for the street vendors who’d slide a thumb on to the edge of the bowl on the scales. Even the parish priest wouldn’t add a prayer to the suffrages at Mass without a bribe. Not to speak of the police. She would always remember this side of her Italian youth. She hadn’t ever known things otherwise.

She wanted to believe him, but such an outcome defied her every experience of life and other people.

But that is indeed how it turned out, the very next day. A neighbour walking down the lane nearby saw something winking in the pale low morning light slanting through the hedge, and picked up one diamond ring, and then, a little further on, another. He (or she – the story is missing fine detail) can’t have driven to the police station because petrol rationing in those years was severe. But whoever it was brought the rings to the local bobby, and when my father, on his way back from London, came in to the police station to report the loss, the constable asked him for some material details to prove that he was indeed the rightful claimant, gave him a form to sign, and a small envelope with the diamond rings inside. He probably added his good wishes for the couple’s life ahead.

It is easy to see this as a lost era of ideal innocence, of honesty, of trust. For my mother the episode took on mythical status, conveying all that she had gained when she left an Italy ravaged by Fascism and factions and fighting, and adopted Englishness. ‘Never ever in Italy would anyone give back a gift from heaven,’ she’d say. ‘They would have just thanked fate and run to exchange it for money – and the jewellers would have asked no questions. It was more than your life was worth to ask questions. Besides, if you had taken such a thing to the police, they would have had you in the cells before you could say Jack Robinson.’ (She’d picked up the local idiom very quickly.)

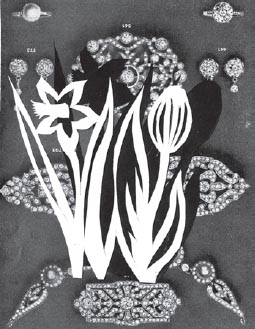

My father went into Ogden’s in the Burlington Arcade to have the rings tightened, and the assistant lent him the right instrument to use to measure Ilia’s finger: a cluster of brass rings in different sizes on a tapered rule. Ilia’s half-moons could then be fitted exactly, and she would wear them every day of her life without fear of them slipping off again.