17

An Old Map

Map of Cairo included in a job lot with seven picturesque prints of Egypt and North Africa; various artists, early nineteenth century. Views of the pyramids, the mosque of Sultan Hassan, and other sights, Cairo, Alexandria, Philae, by O.B. Carter, L. Mayer, Robert Hay et al. The Veduta or panorama by Matteo Pagano (Venice, 1549), nineteenth century, reproduction; this is the earliest rendering of Cairo as a vast and teeming metropolis, packed with services and wonders; Pagano captioned the scenes, his attention trained on the astonishing urban infrastructure, the impressive extent of the city, its serried streets, mosques, enclosed gardens, ordinary dwellings and palaces, the horse traders’ corral, the sultan’s ‘Castel’, the magnificent aqueduct, the Nilometer, warehouses and waterwheels, washing places for laundry, and luxuriant gardens of emirs; he also identifies several ancient monuments – the Sphinx, obelisks, the pyramids, and the City of the Dead. Written in the dialect of the Veneto, his inscriptions provide a guide to pilgrimage sites; the cartouches invoke Faith (Fede), floating above the scene on a cloud with a chalice in one hand and a cross on her shoulder. The stations on the Flight into Egypt of Mary and Joseph and the baby are marked to the west of the city in ‘Matarea’: an enclosed garden behind high walls is identified as ‘The lodgings where the Madonna stayed when she fled into Egypt for fear of Herod’; beneath this scene, the artist labels a tree (‘Pharaoh’s fig’) and declares, ‘This is where the holy family rested in the shade.’

The garden where the true balsam is gathered, with an obelisk. Matarea on a map of Cairo, Venice, 1549.

In the fifteenth century, a healing shrine flourished at El Matareya, which was originally part of Heliopolis, an ancient capital before Al-Qahirah, the Victorious or the Vanquisher, was founded in the tenth century. Near another enclosed verdant garden, the inscription declares ‘In questo se cava el vero balsamo’ (‘This is where you find the true balsam’). The true balm, a sweet, fragrant remedy and solace – prepared as an unguent it can seal wounds, and inhaled in fumigations (as I know), it clears congested lungs and heavy heads, it sweetens stale linen and stuffy rooms, renders flesh intoxicating, and prepares a mortal body to last for ever. It has helped preserve queens and pharaohs, viziers and overseers, and many officials and their families among beloved familiars – cats, shrews, ichneumons, falcons and mice – found, swaddled in cerements, among the treasures in the tombs of ancient Egypt.

I have passed old women in the street in the south – in Naples, in Palermo – and caught that sweet balmy scent from their warm skin, often tinged with light violet or jasmine. In London today, you may be enveloped in a small cloud of myrrh as a woman goes by in the street, swathed head to foot in her black abaya, with her Gucci or Dior sunglasses masking her face.

According to one of the many apocryphal gospels about the Flight into Egypt, this balm was no plant, but the sweat of Jesus.

![]()

One day in 1949, Esmond was putting together some especially beautiful books for the Christmas catalogue – for his new antiquarian section, specialising in rare books about Egypt – and browsing through a small volume he had found in his rummaging about the bookstalls in Ezbekieh Gardens. It was an Italian traveller’s account of a visit to Cairo in the 1860s, with finely drawn engravings (a zebra, the water wheels at Fayoum, an oryx, fellahin picking cotton, turbaned nomads of the Oasis) and lovely fold-out maps throughout, illustrated with more vignettes of typical sights. One map was a panoramic view of the city, and when Esmond had spread it out – eight folds of it – it aroused all his reconnaissance officer’s delight as he fitted what he found there with the city as he now knew it.

The ‘garden where the true balsam is gathered’ would have made little impression on my father had he not come across the story in another old volume, the handsomely illustrated memoirs of Monsieur Benoît de Maillet, a ‘Gentleman of Lorraine’, Consul General in Egypt of the French King Louis XV and ambassador to the court of ‘the king of Ethiopia’. The author’s portrait showed a shrewd potentate in parade armour and full periwig. His Description de l’Egypte came out in 1735, half a century before Napoleon would use the same title for his ambitious survey of the country.

Esmond pencilled in a stiff price – he was confident he could sell this well to the growing number of Egyptophiles among his customers.

Benoît de Maillet, the learned Lorraine gentleman, was also a pioneering evolutionary biologist (Esmond was to discover) and set down an awestruck account of his visit to the part of the city now called ‘El Matareya’. The name means ‘fresh water, new water’, Maillet writes, and claims that the spring was the only running fresh water in the whole of Egypt – ‘perhaps’, he adds, sensing caution is needed. Others suggest it comes from mater, mother, and is named for the Virgin Mary because the holy family stopped there when in flight from Herod. M. de Maillet relates how Joseph gave the baby a drink from the miraculous spring that gushed from the rock for them, and Mary could also wash the nappies of the baby Jesus. The place was, he added, held sacred by Christians and Turks alike. There was a mosque there, and a church, served by Coptic priests.

In a handsome engraving, the miraculous tree stands beside an obelisk, and the author declares the balm was used for the chrism with which babies are anointed at their baptism, and laments that the species of plant is ‘absolutely lost’. Pilgrims reported, he continues, that Muslims prescribed the balm for nasal problems, lumbago or pain in the knees, while Christians recommended it particularly as an antidote to snakebite and other poisons, as well as a remedy for toothache. Monk apothecaries at the shrine did well from the proceeds.

Esmond had never been to El Matareya, a popular, overcrowded, poorer part of the outskirts of the city; indeed, he’d rather avoided going, as it was likely to be insanitary and possibly dangerous. But when it turned out that Florence Nightingale had also visited the shrine, he became very curious indeed. ‘We were loath to leave the garden,’ she wrote. ‘We rode about it and found a broken stone of my friend Rameses, and the well where Mary rested – for Heliopolis has recollections from Moses to Pythagoras and Plato down to Mary – a man with an ass was coming out at the time just like old Joseph. Then we rode home through long avenues to Cairo, the very way Mary and her baby must have come on their road to Fustat; and I thought of her all the way, how tired she must have been.’

The Bible pressed up very close and its dramatis personae became very real. Florence Nightingale was time-travelling back into the wisdom of the past, its philosophers and evangelists and prophets: she felt Plato near, Moses likewise. Egypt was ancient and sacred past, pharaonic and biblical, as it had been for Napoleon and still is for tourists today.

She does mention the fellahin whom she saw as she made her way, and she expresses pleasure at the heartfelt loyalty several of her guides and helpers showed her and her party. But real-life Egyptians around the British, when they were the de facto rulers, remained mostly invisible or, when visible in the old engravings, they’re extras, picturesque Bedouin, or Cairene shopkeepers, in the scenes by visiting artists like Louis Haghe and David Roberts. They aren’t the prime subjects. And I too have found, as I piece together this book of memories, that the Egyptians themselves remain shadowy; to draw them out of the wings is hard. I remember how habitual it was to discount them: a memoir like Lord Edward Cecil’s The Leisure of an Egyptian Official, from 1921, is ruthless, in the comic malicious mode of Evelyn Waugh. The attitude percolated on, right through to my mother, who would say, when Abdel and Mohammed had a long siesta in the heat of the day, ‘That’s Egyptian PE for you.’

The pyramids and the sphinx, as seen on the Veduta or view of Cairo, Venice, 1549.

Esmond, showing the books to Ben Mendelssohn, ‘What d’you think – a staff outing thereabouts? A picnic? Sometime next spring?’ Ben liked the idea: Maisie would enjoy it, he thought. At home that night, Esmond took off his glasses to look closely at the mapmaker’s sphinx: ‘Looks rather ladylike, what?’ He drew Ilia’s attention to the coiled hairstyle and puzzled brow of the sphinx in the map’s engraving. ‘A bit like Lady Killearn on a good day, what? One can’t believe he’d really seen the real thing.’ Then he added, giving his wife a squeeze, ‘We could go for a jaunt and take in the shrine – you’d like that, I think. And it would be just the right thing for Christmas, no?’

![]()

Balm expresses a hope for solace against discontent, for grace, for a way to ensure or return to health; it’s a broad-spectrum panacea. Shakespeare uses it in relation to anointing, to healing, to grace, to sweetness, to desire, to fair speech and caresses – and tears: ‘I’ll drop sweet balm in Priam’s wound,’ weeps Lucrece. Balm was a prize, long coveted and cultivated, but its range is wide, its meanings fluid; it’s synonymous with balsam, but more strongly redolent of fragrance, health, solace, voluptuousness, luxury, bliss: George Herbert taps it in his ecstatic poem, which climaxes on the promise of ‘the land of spices; something understood’. The poem gives a feeling of touching something blissful, but what it is eludes: like the smoke from a smouldering crystal of resin. While the substance itself figures less prominently in everyday life, its meanings have not vanished: the philosopher Agnes Heller, resisting the repressions of Viktor Orbán, wrote from Budapest in 2018 – her ninetieth year: ‘I also participated yesterday at the demonstration; a kind of balsam on our wounds.’ During the Covid-19 pandemic, the voices of Jessye Norman and Kathleen Battle’s performance of the spiritual, ‘There is a balm in Gilead / to heal the sick sick soul’ poured consolation on the nerves of the locked down and isolated, even if I/we weren’t believers.

Sometimes the word acquires a tinge of luck, and is used interchangeably with ‘manna from heaven’ – a sudden windfall, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow (calls for funding from supporters sometimes invoke it: the magazine Cabinet asks donors, ‘Please mark the envelope, Balm from Gilead’). It’s one of those biblical phrases, like ‘eyeless in Gaza’, ‘Gadarene swine’, ‘apple of my eye’, ‘the golden calf’, ‘the widow’s cruse’, ‘a horn of plenty’ and ‘the voice of the turtle’, which contract their claws into the mind because they’re so odd.

This solace, this dew of grace, this balm of Gilead, was what Esmond wanted when he left – when he fled – post-war England with his family for Egypt, abandoning cold, bomb-scarred, soot-laden and ashen London, where there was little prospect of a job for him. Although the dust of Cairo was also thick with sand from the desert, it didn’t carry with it the cinders of corpses.

In a wet country like England, rain isn’t often longed for as keenly as it is in the Psalms (at least not until recently when climate change has brought drought). Yet the many verses casting God as a generous rainmaker, plumping the harvest, bedewing the flowers, reflect wishes in arid conditions. Many examples could be given of depths of disconnection between the imagery of the Bible and the climate and circumstances of its readers, in, say, Surrey. Yet the lines are thrilling: ‘I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys. / As the lily among thorns, so is my love among the daughters.’

Balm grew there, on thorny bushes, among the roses and the lilies. Balm would flow for him here, in Cairo, his second home.

![]()

Esmond was one of the many visitors who romanced the south – North Africa, Egypt, Sicily and southern Italy, where the war had taken him. For him these landscapes and their culture were bathed in colours and scents and sensations that his own world – which is still mine – has beamed on to the region through Herodotus, the Bible, Napoleon, Florence Nightingale, on and on. Balm belongs in this story of Esmond and Ilia and their lives in Egypt because, like so much of the imagery of the Bible, it infuses the territory where the sacred stories happen with sensuous, voluptuous pleasures: the ultimate sacred places are conjured by strange substances, and paradise itself is clothed in incomprehensible words: ‘Take unto thee sweet spices, stacte, and onycha, and galbanum; these sweet spices with pure frankincense: of each shall there be a like weight: And thou shalt make it a perfume, a confection after the art of the apothecary, tempered together, pure and holy’ (Exodus 30:34–5), says God to Moses, while the vision of the New Jerusalem, arrayed as gloriously as a new bride, dazzles with exotic phenomena that I for one could not match to anything real when I first met them in the course of readings during the Mass: ‘Thou hast been in Eden the garden of God; every precious stone was thy covering, the sardius, topaz, and the diamond, the beryl, the onyx, and the jasper, the sapphire, the emerald, and the carbuncle, and gold: the workmanship of thy tabrets and of thy pipes was prepared in thee in the day that thou wast created’ (Ezekiel 28:13).

What is sardius? What is that carbuncle in Eden?

No matter what it means or refers to or how it could belong in reality; the scene seduces, it palpitates with life.

![]()

The phrase ‘balm of Gilead’ first appears in one of the prophet Jeremiah’s loud protests at the fallen state of the people of God: ‘Is there no balm in Gilead,’ he rails, ‘is there no physician there?’ (Jeremiah 8:22). Berating the Israelites for faltering in their beliefs, the furious holy man compares them to a sick girl needing treatment: ‘Why then is not the health of the daughter of my people recovered?’ He was writing this from Cairo, as Florence Nightingale noted with a frisson of pleasure when she visited the synagogue in the old fortress, and remembered that the prophet had been living and working there. ‘If I can believe,’ she writes, ‘that here Jeremiah sighed over the miseries of his fatherland – that here Moses, a stronger character, planned the founding of his – that here his infant eyes opened, which first looked beyond the ideas of “fatherland” … is not that all one wants?’

The people in Gilead have as much balm/rosyn/sweete gumme/triacle (translations of scripture vary), Jeremiah thundered, as needed to heal every ill – the presence of the one true god. But can they see this? No. They’re faithless, and on top of this, murderers of their neighbours the Ephraimites for not speaking proper (though the prophets don’t usually preach loving kindness across ethnic differences). You have the one true god, Jeremiah thunders, you scoundrels, just as you have delicious precious balm/rosyn/sweete gumme/triacle, so why are you so lazy, unbelieving, sinful, weak and wicked?

When Myles Coverdale renders the phrase as ‘Is there no triacle in Gilead?’, the word he chose comes from theriacum, from the same Greek stem as ‘therapy’ and ‘therapeutic’. Before there was treacle tart and golden syrup, ‘treacle’ was a medicine, especially for eye diseases, snakebite and menstrual cramps. Like ancient Egyptian mummifying ointments it could preserve and reinvigorate. It described sweet-smelling substances, such as the precious oil Mary Magdalene pours on Jesus’ feet, and which she carries to the tomb after his crucifixion, in preparation for tending the dead body. Mixed with sulphur, it was a widespread remedy well into modern times: a dose of ‘brimstone and treacle’ is favoured by Mrs Squeers in Nicholas Nickleby and much feared by her charges. The miraculous ‘treacle well’ wasn’t a joke, as Lewis Carroll knew, during that summer afternoon on the river in 1845 when he started telling Alice the famous story of Wonderland. A deacon talking to the children of the dean of Oxford Cathedral, he was fully aware that he was making a kind of clerical joke, poking fun by drawing on a word now obsolete, but which had been used for the holy spring at Binsey, which helped sufferers from eye diseases and sexual problems. The well is still there, a mossy puddle like a cyclopean eye in the ground of the cemetery, and seems no longer in use.

When the angry Jeremiah uses the phrase ‘balm in Gilead’, he’s reaching for a figure of speech; it’s not certain that Gilead itself, a large territory in east Jordan, beyond Galilee, was a prime source of the healing stuff. But the phrase stuck.

Look up ‘balm of Gilead’ in dictionaries and the terms go wandering through the column lists of plants, untethered to exact species. Besides frankincense and myrrh, there’s terebinth, storax, spikenard (which just means ‘spicy ointment’), all fragrant, all essential to the art of perfumery. They derive from multifarious commiphora and opoponax shrubs, yielding fragrant gums and resins, and the bounty they give seems all the more wonderful because the plants are so thorny and the terrain they grow in harsh and dry. Balm is from Latin balsamum, from Greek βάλσαμον meaning ‘balsam-like’ in the sense of ‘restorative’ or ‘curative’. The Hebrew Bible’s tsori, a word for balm, simply means to flow. Kew Gardens’ Plant List for 1913, under Commiphora gileadensis offers a rigmarole of synonyms as successive flower hunters kept bidding for a moment of eternity through naming specimens after the biblical phrase. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, a self-styled wise man, Samuel Solomon, concocted a proprietary ‘cordial’ to a jealously guarded secret recipe, called it ‘Balm of Gilead’, and marketed it as an infallible and very expensive cure for ‘the consumptive habit’ – that is, male masturbation. It made him a considerable fortune. Meanwhile, balsamic vinegar, now a staple of the modern kitchen, doesn’t include any botanical balsam at all, and that goes for the most expensive vintage decoctions from Modena.

The word Gilead means little to most people now – or didn’t do so until Margaret Atwood adopted it as the name of her nightmare state in The Handmaid’s Tale (1986) and The Testaments (2019); she is playing with heavy irony on the word’s associations of comfort to capture the regime’s double-speak, as its Commanders promise protection and well-being to the women they enslave. And now, as I write, during the full onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, a pharmaceutical company called Gilead Sciences is starting trials on a cure.

![]()

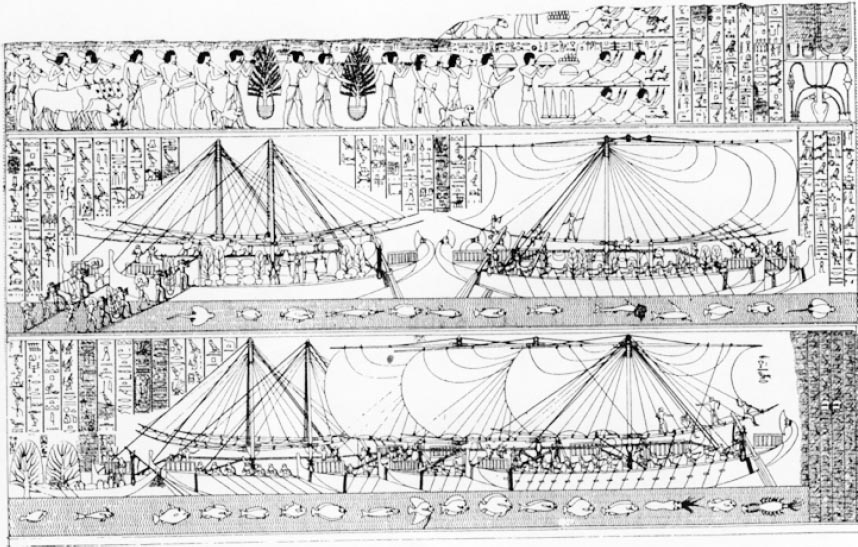

Queen Hatshepsut’s boats being loaded with monkeys, panthers – and balm trees, wiith their root balls intact (upper row). Bas relief from Deir al-Bahari, Luxor.

Hatshepsut’s funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari, on Luxor’s West Bank, is decorated with an intricate and crowded frieze of bas reliefs, showing the expeditions ‘the female Pharaoh’ organised to the land of Punt – Punt’s exact whereabouts are still a mystery – to bring back treasures such as sweet-scented myrrh trees. The paintings have faded to wraiths, but an archaeologist made drawings in the nineteenth century, and they show Hatshepsut overseeing the transshipment of specimens. This ruler, her botanists and plantsmen, were the first people ever to think of transporting living mature plant specimens across great distances and replanting them. Two of the ships are being loaded with precious cargo – monkeys, panther skins, ebony and, the inscription proclaims, ‘all goodly fragrant woods of God’s Land, heaps of myrrh-resin, with fresh myrrh trees’. The queen ruled over a prosperous and largely peaceful kingdom for fifteen years, from c.1473 BCE to c.1458 BCE. As the first plant-hunter on record (setting aside Gilgamesh’s quest for the plant of immortality), she made Egypt a prime cultivator and trader in such goods. She dispatched her most learned court botanist, supported by two expert plantsmen, to strike a deal in Jericho, where gum-yielding bushes and trees grew in abundance, and bring back specimens. She planned to plant them in the equally stony soil of the desert on the outskirts of Heliopolis, terrain as dry as the bush’s natural habitat in Judaea. A millennium before the star led the three kings to Bethlehem, Hatshepsut had understood the preservative power of the sticky scented stuff and the consequent riches it might reap for her treasury – she was ruling over a people for whom overcoming decay was a paramount concern, and who knew how to futureproof so cunningly that their corpses remain the prime attraction in museums in Egypt and elsewhere. When Jacob is planning to ransom Simeon from captivity in Pharaoh’s court, he tells his other sons to take balm to the Egyptian official in charge, who is, unknown to them at this stage, Joseph, the brother they left to die in a well.

The threads of the story of the true balm are all entangled with several other female rulers: the Queen of Sheba who, when she came from the south to put hard questions to Solomon, presented him with, among many other treasures, slips of balsam which the king planted in a hortus conclusus (an enclosed garden) near Jerusalem; later writers described it as part of Herod the Great’s palace in Jericho. And according to Josephus, Mark Antony confiscated Herod’s garden where the trees grew, and handed it over to Cleopatra, in 34 BCE.

It seems that the land of spices must be a queendom.

The garden of the True Balsam in El Matareya doesn’t claim Hatshepsut or the Queen of Sheba or Cleopatra as its founder, but instead it gives the Virgin Mary the role as its genius loci. Another Mary – the Magdalene – also plays a leading role in the story, when she pours her oil on to Jesus’ feet – provoking the enviers and hypocrites at the dinner party to object loudly that she was squandering it, and besides, it was ill-gotten gains, the wages of sin. Mary Magdalene, the prostitute who repented her ways, takes a prominent place in the tight historic intertwining of women, power and perfume (at airports, in an early morning daze before your flight leaves, you will be led through a gleaming meander, past crystal phials and gilded stoppers, and you will be solicited by beauties, male as well as female, with their speaking looks and gold-dusted skin, to buy mysteriously expensive perfumes with oriental names – Samsara, Shalimar).

Ilia knew her saints – and among them many whose bodies drop balm (they are technically termed myrrhoblytes – myrrh-givers). In her home town, the body of San Nicola still oozes a precious ‘manna’ from an orifice in his sarcophagus. When my mother and I went to Bari for what would be her last visit, I accepted the sample from a priest and tasted it – it was odourless and without flavour, neither redolent of rotting corpses nor the perfume of sanctity – unlike mumia or ‘mummy’ which was a popular pick-me-up from medieval times into the nineteenth century. It’s said that François I, King of France, never ventured out without some.

San Pantaleone is another saint who still yields a life-giving balm. The patron saint of Ravello, he was a Roman doctor martyred in one of the great persecutions. On his feast day every year – 27 July – his blood liquefies. I came across the miraculous vial behind the high altar in the duomo there, as Esmond and Ilia may have done when they were there on their honeymoon in 1944.

The saint and her precious jar of balm, Jan van Scorel, Mary Magdalene, c.1530.

A jar of precious balm is the attribute of the Magdalene, and although it changes from artwork to artwork, setting off artists’ most lavish powers of invention, she always carries a variation, often fantastically opulent. Museums display these precious flasks for oil from ancient times, and label them ‘alabastron’, ‘unguentarium’, ‘lekythos’, ‘pyxis’ – these special words, their elaborateness matching their subjects, add to the aura, especially as they’re now ‘obs.’, out of time, like the vessels themselves (though in the fight against plastic, they might make a comeback). In many pictures Mary Magdalene has set down such a vessel on the floor beside her at the banquet in the House of the Pharisees, to wash Jesus’ feet with her tears, drying them with her hair and then pouring out the unguent in her jar over them, and kissing them again and again.

The tree which bleeds this precious scented balm is no beauty: the scaly bark, a sickly yellow, desiccated and peeling, is studded with long, sharp needles, to repel all predators. Only the toughest goats nibble it (and goatherds then comb the precious nuggets from their beards). As hedging, the thorny branches provide humans – and their herds – with spiky defences against all intruders, a natural bulwark or chemin de frise, but they are also cruel to handle and harvest, and can inflict deep gashes on the unwary. They have a stringy taproot that plunges deep into the loose dry listless soil; if you slash at the branches with a cutlass, they aren’t as dry and dead and brittle as they appear, but sinewy, and where the blade slices through the stem, drops of gum bubble up through the lesion and collect there in glistening beads. What soothes and cures and calms stems from a wound.

This gum is dull, sticky, and sallow like the bark, and dries into pellets like crystallised sugar, the kind that Ilia served with after-dinner coffee and used to let me spoon up from the bottom of her cup just before it dissolved: a delicious crunchy sweetness. But you can’t eat the amber nuggets of incense, only burn them for their fragrant smoke or grind them to suspend them in another medium. You can sniff them and savour them, and the resin can be rubbed, warmed, mixed, dried and burned, to give out the sweetest scent, light and fresh as dew, gentle as a baby’s skin, pure as fresh water, a perfume of rejuvenation and beauty, promising conquest over the ravages of time and the putrefaction of flesh: a scent of paradise.

Accordingly, Commiphora myrrha (the current favoured botanical term) became very sought after indeed. Its price per ounce rose and rose, the trade was keen, and the garden of the true balsam, even as it struggled to survive in the middle of a hectic and populous outer district, remained a key supplier to the perfumiers and traders in spices from the suq of Old Cairo. Today, this dry, fierce and spiky bush is the only thing that grows in Dadaab, the largest ‘Refugee Complex’ in the world, a vast temporary/permanent improvised conurbation in Kenya, which gives shelter to more than 300,000 refugees, most of whom are Somalis fleeing war. They fence their homes using the only effective means available, which happens to be the thorn bush, in more peaceful times a source of revenue and luxury, but now simply organic barbed wire: Dadaab has become known as the City of Thorns. Yet these barbed and scraggy growths produce myrrh, that most luxurious of substances. What an irony that myrrh should drip from gashes in their bark.

During the parish priest’s sermon on the Maddalena’s feast day, Ilia wondered how the saint could have wept such a quantity of tears that she washed Jesus’ feet. But the thought was still thrilling – as it was for me, when I was growing up and the scene was painted and praised by Mother Bridget during lessons, explaining that the Pharisees didn’t understand anything about goodness, especially when they objected to the Magdalene’s actions, saying that if Jesus was a true prophet, he wouldn’t let such a woman come near him, let alone touch him. But Jesus liked to forgive women – he was tougher on men like the centurion, and hard on fig trees – but if you had a flux of blood, he could stop it, and if you had had seven husbands, he wouldn’t turn his back on you, and if you had been taken in adultery, he wouldn’t join the mob who wanted to stone you to death. He bent down instead and wrote in the dirt, ‘Let him who is without sin cast the first stone.’ (He could write! Is this the only moment in the Gospels when we see him doing so?) Likewise, Jesus dismisses the outcry against the woman pouring the expensive balm on his feet and drying them with her hair and her kisses. He makes that famous statement, ‘Wherefore I say unto thee, her sins, which are many, are forgiven; for she loved much’ (Luke 7:47).

But what kind of love? Ilia wondered. What did Jesus mean? I wondered, too, later on when I was struggling with my faith and its ideas about sin and the flesh. Love was tangled up with generosity – indeed with prodigality, it seemed, and that gave rise to an expectation. Presents were the guerdon of love, and Ilia, who was so thrifty that she picked out from her discarded outfits the zips and buttons and even sometimes pulled out the thread from the seams and wound it on a spill of paper in order to reuse it, still felt that lavish gifts were a true expression of love. And Esmond had begun so strong and indefatigable in his hunt for gages d’amour, love tokens, for the shining bale of exquisite, featherweight tulle, for the diamond rings his mother had given her, which she nearly lost.

Recently, there’d been episodes; she didn’t want to linger on them, but they would buzz in her consciousness, like a fly that, swatted, still spins upside down on a tabletop, refusing to die. It was a Christmas party – 1949 – and they’d been invited to a supper dance at the Auberge des Pyramides (in a photograph, Ilia is wearing a conical party hat), and she’d been dancing to the big band, with Seddiqi Pasha and Jamie Chantry and Ben Mendelssohn and others. Esmond would dance, occasionally, but he liked her to dance more. He was a poor performer, he would say, though this wasn’t strictly the case; the reason was, she knew, that he preferred to play cards.

Esmond, waving, with friends, and Ilia, right, in party hat and gown. Christmas party, 1949.

She was going back to their table, laughing, a bit puffed, when one of the waiters in his maroon tunic and sash came up to her and with a small bow whispered, ‘The chef would like to thank you in person in the kitchen for your kind congratulations.’

Ilia was startled, and as her lips parted to exclaim that the message couldn’t be for her as she had not thought to congratulate the chef, though he did indeed deserve such; even as these words were forming on her tongue, she caught a slight widening of the pupils in the nadil’s eyes, and it stole the breath from her lips, and she dropped her head in response; yes, she would follow him.

She put on a brave smile as she passed knots of other guests; some at the small round tables, some standing waiting for the band to begin the next set, many of them in funny hats like hers, and the drifting smoke from their cigars and cigarettes wreathed about them. Where was Esmond? She hadn’t seen him for some time, she realised.

She followed the waiter out of the ballroom and into the corridor past the door to the card room and down more of the corridor till they reached a pantry and there was Esmond sitting on a chair groaning, his tie pulled out of his stiff collar and everything, everything undone.

‘Thank God you’ve come, baby,’ he said. ‘Take me home.’

She fled to him and then turned to the man who’d been with her, but he’d been replaced by two others, the sufragi from the foyer, and another of the hotel front-of-house staff – maybe the concierge, she realised, because both of them were in full hotel uniform with tall turbans and long maroon coats. She began crying, as Esmond muttered choppily at her, ‘Oh, don’t cry baby, don’t cry, just get me home.’

‘We’ve told the driver to come around to the back entrance,’ one of the men told her. ‘We can leave through the kitchen.’

‘What happened?’ she cried.

‘Bloody fool, can’t count to thirteen.’ He was trying to shout, she could see that, but the words came out in a kind of croak instead.

‘Oh, it’s just the gentlemen’s ways, my lady,’ said the footman. ‘Nothing to worry about.’

She tried to tidy Esmond a bit before they hauled him to his feet, a dead weight, his head rolling as he moaned again.

Back at Soliman House, she woke Abdel and Mohammed and brought them downstairs in their pyjamas to give the doorman a hand in bringing Esmond home.

They too did not seem surprised or perturbed, and this reassured her. Perhaps, growing up among her sisters with her mother a widow, she just didn’t understand much. She thought Esmond would explain, but he never mentioned it, though he did keep away from the card room for a while.

But later, the flow of Esmond’s love would change course, and he’d spend his money on his clubs in London and on the subscription to a livery company and doing the rounds of the salesrooms and buying pictures and silver and china which he liked. There would be terrible quarrels: ‘I would like a new overcoat this winter,’ she would ask him. ‘It’s been ages since I bought mine, and I have to wear it every day …’ Unspoken, her sadness at the long lightless winters; unsaid, the cold inside the house which meant she wore it inside, too.

He would pull at his jacket and turn out the breast pocket to look at the tailor’s label: ‘Look, my dear,’ he would say, with a gratified chuckle, ‘Cairo, 1948, and still going strong. Why want a new coat! Absolutely no need. Pure nonsense.’

These stand-offs, which would leave my mother shaking with tears, determined me never to be in the position that she was in, having no money of her own.

![]()

My young mother was taught a woman’s body is dangerous, filled with powers that she could use: it radiated from her like a fragrance, but it was devil’s work – she was an occasion of sin. Her dressing table displayed her scent bottles and cosmetic jars, some of them glass with silver lids engraved with the coat of arms of Mother Rat’s father (they had come from his gentlemen’s toiletry box); to her delight, she was given a bottle of Miss Dior for Christmas the year it was newly created to accompany the couturier’s sensational post-war collections. Esmond couldn’t afford the perfume itself or the eau de parfum, but only the eau de cologne, which was packaged in black and white houndstooth – a sporty touch, at variance with the light heady perfume. (By the way, this was another class shibboleth: she taught me, ‘Always use the word scent. “Perfume” is vulgar.’ Euphemisms, as ever, conveyed suspect genteel pretensions to be condemned as ‘phoney’. Later, when Diorissimo came in in 1956, she switched – she was a mother of two daughters by then, and Miss Dior was for a bachelor girl.)

The priest in San Nicola whom the 14-year-old Ilia heard giving the sermon on the Magdalene’s feast day, 25 November, explained that Mary Magdalene pouring out the oil that was so expensive showed that what matters is love, not money. The Pharisees overvalued money when they muttered that she should have used her ill-gotten gains to feed the poor. Magdalene’s tears gushed so profusely they made enough water to bathe the dusty feet of a man who had been walking in the hot desert and the stifling streets, her hair flowed so abundantly she could use it as a towel and then she lavished on him the oil and the kisses, and he liked it, he said she was forgiven all her sins. The salve she did not stint on her beloved master was to bring about her salvation. But when they said she had loved much, did they mean she had slept around? It sounded like that. We women are all occasions of sin, Ilia knew. The Devil’s gateway. The saints had been tempted and managed to resist the overtures of ‘bevies of wanton girls’.

The sinner who lavishes the precious oil on Jesus’ feet has no name in Luke’s story, but from the beginning she was conflated with the woman who had seven devils conjured out of her by Jesus, and with another, called Mary Magdalene whom Jesus was very close to and, yet again, this Mary was bundled together with the Mary who is the sister of Martha and Lazarus, who all lived in Bethany. This composite persona was also thought to include the woman who goes to the tomb to care for the body of ‘her lord’ after the crucifixion, who, three Gospels report, has the exceptional privilege of being the very first person to see the resurrected Christ. But on this occasion, she mistakes him for the gardener, and when he reveals himself to her as her beloved master, who has risen from the dead and left the tomb where he was buried, she tries to embrace him, crying out ‘Rabboni’, my lord. But he holds her off: Noli me tangere. Do not touch me.

Did Jesus wave away Mary Magdalene because her touch would have sullied the heavenly body of the risen Christ? Like an oily fingerprint smear on a clean glass? She was a prostitute, that was assumed, and she was rich because she had sold herself, gaining her great wealth in the process, and she bitterly repented her sins for the rest of her days, stripping herself of all her jewels and finery which lay scattered about her as she wept over her jar in the rocky cave where she withdrew after she was changed, altogether changed, by meeting Jesus. It was all very puzzling.

Much later the same scene was described to me by my father’s friend, my godfather Frank who, as a Catholic convert, would all of a sudden remember his pastoral role. I tried to point out that there was no reason to assume that Mary Magdalene’s money could be made only through sex or that she could only afford that expensive oil in its expensive jar because she was putting herself up for sale. Frank looked startled. ‘She had loved much,’ he said, ‘and a sinner who loves much can’t be anything else than a tart – not that I am condemning her for that, you understand. I know what the world is like for women who have no chances in life.’ This was the time when he was cleaning up Soho, campaigning against the growing freedoms of the 1960s and making common cause with the protestor Mary Whitehouse, who attacked foul language on the BBC. He wasn’t a Puritan, but more of a sympathiser, and he identified with Jesus and had a very soft spot for sinners, especially sex sinners.

Frank and I always met in Soho. He’d resigned from Wilson’s Cabinet when they didn’t raise the school-leaving age as they had promised to do, and become director of Sidgwick & Jackson, a publishing house with a historic interest in Catholic matters. He’d invite me to one of the old-established restaurants near his office, which were, literally, plush, all muffled in velvet and linen, as if no conversation should ever be overheard: Kettner’s in Romilly Street, the Gay Hussar on Greek Street, Quo Vadis on Dean Street. I was beginning to earn some precious money of my own, but I still had no grasp of what things cost or how valuable time is, and Frank’s generosity towards me didn’t surprise me as it should have done. We talked about Esmond and his exploits: how he had broken a golf club in a rage at a caddy one time when Evelyn Waugh was present and had cowered in terror in the nearby bushes … how Esmond was so clever he should have done more with his life … and so on. At the coffee stage Frank would remember his duties to my spiritual welfare. When we left the restaurant and were walking together down the street, friendly cries rose here and there, from doorways and passers-by. ‘Lord Porn!’ they cried, ‘How are you doing today?’

During the years of his alliance with Mary Whitehouse, he was also a passionate advocate of prison reform and instituted the parole system. As a Catholic, he believed in personal redemption. Most famously, he took up Myra Hindley’s case, believing she had repented. In the early 1960s, when another series of sex crimes began spreading terror through Cambridge, Frank was agog that Esmond had employed the man known as ‘The Cambridge Rapist’ – these were the words the perpetrator had painted on the zipped leather hood he wore when breaking in on nurses’ hostels and student digs. By a twist of fate, he turned out to be a van driver for a local wine merchant’s, who, on dropping off an order, lingered and asked Esmond one day: ‘Any odd jobs needed round here?’

There were, several, and thereafter Peter Cook – that was his name – became a regular at our house in Cambridge, cleaning out the gutters and drains, trimming the roses rampant up the walls. When the attacker had been identified and arrested, Esmond took to enthusing that he could now outdo Frank in the notoriety of his acquaintance. The Cambridge Rapist was almost as notorious an offender as some of Frank’s dubious protégés. He immediately wrote to Frank to inform him. He imagined he would get to see Peter Cook before Frank, and he wanted to; the man was a mystery and, as his occasional employer, he felt he had a right to understand more. A policeman came to vet Daddy, and I heard his guffaw, as he told the sergeant, ‘Peter Cook’s a very fine chap! A hard worker. Can’t imagine that he’s done such things.’

The police sergeant nodded and wrote it all down in his little black book. This visit was followed up by an official letter denying Lieutenant Colonel Warner permission to visit the prisoner, who was now in Broadmoor.

We – the women in the family – were spooked by this strange twist of fate. Ilia remembered with a shiver how Peter Cook tossed rose cuttings at her from the ladder he was using to prune. ‘Here comes another, Mrs Warner, watch out!’

‘That’s not funny, Mr Cook. Now stop it.’

He was whooping with delight as he lobbed another thorny stem at her.

‘I told you to stop. I mean it. Stop.’

But my mother had to move her garden chair to get out of his reach.

Worse, Laura had been sometimes alone in the house, doing her homework, while Peter Cook was there, and the police had found a photo of her in his wallet. She was then a willowy teen in tiny skirts, with huge eyes and long wavy hair which she wore in an Alice band for school but let loose on other occasions: a Pattie Boyd lookalike at the height of Beatlemania.

Later, from Broadmoor, Cook petitioned to have a sex change to control his urges, he said.

![]()

When Ilia was growing up, not loving meant not letting men touch you … there or there. Yet Mary Magdalene’s hair flowing down and covering the man’s calloused heels and soles, the unsealing of the jar and the stickiness that must have covered her hands and her mouth and all that hair after she poured out its fragrance – the scene made Ilia’s insides squirm, for reasons which were not clear to her yet, but would be when that body of hers, inside which her spirit struggled like a moth between a shutter and a windowpane, became visible to her through the admiring eyes of men, who would bring her perfume, nylons and jewellery.

The jar of fragrant oil was alabaster, Luke tells us, and when she carries it to the tomb she is known as a myrrhophore, a myrrh-bearer; when artists imagine it, they borrow from the luxurious flamboyance of the Magi’s vessels – the wise men or kings who followed the star were also travelling a trade route in spices from the East, and artists vie with one another to represent the jewelled receptacles which enclosed their gifts.

Mary Magdalene in Roman Galilee would hardly have owned such a fabulous jar, however successful she’d been at her (reputed) trade. But the paintings are telling us that what we are seeing is a miracle, the outer sign of inward grace. She carries the miracle she is about to take part in – her own conversion through prodigality and love – in the form of a jar, a jar that is usually lidded, since it holds its precious contents safe, and prevents their perfume from being squandered into the air like bottles of expensive scent left unstoppered on a careless diva’s dressing table. (‘Always remember to keep your powder compact closed,’ Ilia would tell me, ‘so the lovely, delicate fragrance doesn’t fade.’)

Artists rarely choose alabaster, as specified by Luke. Instead they conjure up vessels coruscating with gems and bristling with gold knobs and spires and finials; the penitent saint holds it near her body or displays it by her side or sets it on the ground next to her as she kneels and bends to minister to Jesus’ dirty feet. It’s sometimes a chalice, or more specifically, because it has a lid, a ciborium, as used to conserve hosts inside the tabernacle, after they’ve been consecrated – transubstantiated into the body and blood of Jesus – and so mustn’t be trifled with. The treasuries of rich pilgrimage churches and cathedrals often display ‘chrismatories’ too, special goblets for a travelling priest to carry to a sickbed or a deathbed. Such vessels belong in a range of luxury wares – table pieces, épergnes, and extravagant ‘salts’ with bathing nereids, dolphins and palm trees … If Mary Magdalene and her rich dresses don’t look sumptuous enough, her jar makes up for it, signalling the ultra-preciousness of the balm that she brought to soothe Jesus’ feet and, at the same time, beaming out the fabulous promise of her body.

Like Pandora, whose charms are all mixed up with the box she opens, Mary Magdalene is identified by her jar. From one work of art to another, it shifts and changes. Bernardo Luini, a follower of Leonardo in his love of soft, sfumato shapes, shows the saint pinching the knob on the lid to lift it, as she eyes us, as if daring us to come closer and have a peep. Under that half-lifted cover and her delicately splayed fingers holding the knob, the concealed contents take on a mysterious, secret character. ‘Acqua cheta,’ Ilia would warn when she was talking about someone who put on every appearance of demure virtue. ‘Acqua cheta rompe i ponti – it’s the quiet ones who are dangerous,’ she’d say. The proverb’s not quite the same as ‘still waters run deep’, but close. She’d also say, meaningfully, ‘In bocca chiusa non entrano mosche’ – literally, ‘no flies go into a closed mouth’; she translated this as ‘silence is golden’. But it verges on ‘butter doesn’t melt in her mouth’.

All unconsciously, Luini is touching on a highly suggestive, nigh lewd correlation between Mary Magdalene’s body and the sweet juicy balm inside the pot. The motif recurs again and again in pictures of this saint: Jan van Scorel’s well-rounded (an Ilia term) Magdalene, seated with a very large, tall jar on her lap, regards us foxily sidelong, against a craggy landscape of clefts and hollows.

![]()

As I moved among my ghosts and rummaged about in the past and tried to find my way back through the darkness that wraps them, these scents rose all around me – fumes of rose water, pistachios and icing sugar from the Mouski, chlorine in the swimming pool at the Club, seaweed and stranded jellyfish drying out on the beach at Alexandria, the sand and dust tang of the wind from the desert. Frankincense and myrrh burning in censers inside the flat and the houses of friends. The dust from the desert gently powdering the surfaces all around. Sugar melting in pans to make syrup. My mother’s dressing table glinting with glass. I knew it was an illusion, but the painting on the lid of the compact is an illusion: Georges saw Ilia through smoke rising from shared dreams of oriental pleasure, ‘all the perfumes of Arabia’, which Lady Macbeth cries out ‘will not sweeten this little hand’.

The Virgin Mary rises from her tomb to ascend to heaven in her body, and drops her sacra cintola, or belt, to convince the apostle Thomas. Cola dell’Amatrice (Nicola Filotesio), triptych of The Assumption of the Virgin, 1515.

While I was trying to understand the uneasy excitement Mary Magdalene’s jar set off in relation to Ilia in those days, I came upon a triptych of the Virgin’s Assumption into heaven by Nicola Filotesio, known as Cola dell’Amatrice after his birthplace, a small earthquake-shattered town in the hills inland north-east from Pescara. During his lifetime, Amatrice was riven by gang warfare, and the artist ended up on the losing side, and had to flee. Vasari condemns Cola’s art as irredeemably provincial, but relates how, when Cola was being hounded out by a furious crowd, his wife threw herself over the edge of the mountain road. It was an act of despair, Vasari says, and he is very moved by it. Her action gave their pursuers such a shock that their fury subsided, and they abandoned the chase: ‘thanks to the sacrifice of his beloved, without doing Cola the harm they had intended’.

Cola twisted his figures and painted grimaces of agony on their faces, and these contortions might arise from his own troubles. (But they’re also stylistically typical among artists in the region – Carlo Crivelli and Cosimo Tura, for instance.) Cola’s Mary Magdalene does however suggest some deeper disturbance: her throat and forehead and bare feet uncovered, dressed in shades of red – pink to ruby – she’s holding the jar below her waist in her left hand and the tall knob on the lid is topped by what can only be seen as a glans-like protuberance; this pokes up towards a deep cleft in the heavy pink labial folds of her overgarment, preposterously arranged in an open inverted V, and tucked into her belt. Fleshy in hue and texture, a lighter pink than the rich ruby reds of her outer clothes, it seems to display a tender vulva opening to the upstanding lid of the jar of ointment, while her upturned gaze and bared throat recall the amorous expectation of Danae irradiated by Zeus in a golden shower or the blissed-out face of Santa Teresa of Avila receiving the burning point of the angel’s lance.

The Devil’s gateway!

The penitent Magdalen, left, gazes in awe at the incorrupt Madonna. Cola dell’Amatrice (Nicola Filotesio), St Mary Magdalene and St Gertrude / Scholastica [?], left-side wing of the Assumption triptych, 1515.

Redness carries associations – with heat and flesh, with beauty and danger. Mary Magdalene is a scarlet woman. Blushes and flushing, those rushes of blood to the cheek, bring rubies quickly to the poets’ imaginations. ‘Who can find a virtuous woman?’ asks the writer of the Book of Proverbs (another cynic about sex and love), ‘for her price is far above rubies’ (31:10). I may have a prurient mind and be seeing things, but I am reminded of the title of the book by the unhappy actress Carrie Fisher, called Surrender the Pink (1990).

Cola’s painting, which glows with crimsons and scarlets, offers us carnality as its implied subject: female flesh redeemed, made radiant by sanctity and freed from mortal troubles, as promised by the imperishable body of the Virgin going up to heaven.

Throughout her life Ilia kept the gold medallion of Our Lady that her mother had given her to wish her luck in her marriage. She believed she would be rewarded if she tried to be good. She did try to be good, especially as a wife and mother, often to her great cost.

![]()

‘The muse has left me,’ Dimitrino said, with a frown, ‘since the war, since all this …’ he waved at the company and turned to Ilia. Had she seen anything of the landscape beyond Cairo? he inquired. Yes, she told him she had visited the pyramids and the Mena House Hotel. She was always drawn to a sad person and her sympathy spurred her on to gaiety to cheer them up.

‘Esmond is planning a staff outing to the Nile barrage in the Delta,’ she began.

He nodded approvingly. ‘You will see heron … and egrets of course, and falcons … kites … vultures.’ The birds hadn’t changed, these were the same species that the ancient Egyptians had soaked in balm and then wound in basket-weave mummy bands: time was racing past now, and only last year and last month and last week seemed to have vanished to a far horizon, while the past, the past of Canopic jars and their treasured contents, that past was still here. Dimitrino wasn’t able to write such things any more, couldn’t find room to breathe in the post-war jangle as rival forces pulled at Egypt this way and that.

Noticing the medallion at her neck, he asked her about it, and Ilia told him she was from southern Italy where everyone was Catholic. He replied that there was an old oasis in a faraway part of the city near the old capital Heliopolis, where there was a shrine to mark the spot where the Rest on the Flight took place.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I think Esmond …’ she paused, she was always careful with a man not to know more than he did, and he was loosening up, unexpectedly. He offered her a cigarette, but she never smoked.

‘Your husband likes this brand, I know.’ He was smiling. ‘No? You don’t share your husband’s tastes? Ah well. The tree that bent down to offer dates to the baby, that is there, I can show you.’

She felt he was mocking her, but flirtatiously, and she was enjoying herself.

His expression turned serious. ‘There is a cave there, where the holy family hid. A spider wove her web over the mouth and so their pursuers passed on by, deceived into thinking nobody had entered it for years.’ He was looking at her, still straight-faced. ‘I think the same miracle helped the Prophet when he was in flight from his enemies. Maybe it was the same spider? They live a long time, I believe.’

Ilia laughed.

‘No, it is not funny. It is wonderful. And the ointment Mary Magdalene uses when she washes Christ’s feet, it was brought from Cairo, my dear Madame Ilia, from the garden of the true balsam, where monks prepared it to a recipe that remains secret.’

![]()

Later, Esmond confirmed, Dimitrino had recently purchased an expensive album of Egyptian birds, by a certain G.E. Shelley, a captain in the Grenadier Guards and a keen shot who had reconnoitred the hunting grounds of the Nile. It was filled with species that were less common sights today, said Georges. ‘You know the book has marks in the margins: a Greek delta against a bird he had bagged, and an S when he’s had a skin prepared, and three crosses for birds he “very much wanted” to see … the sacred ibis! But these were already pretty nearly extinct then – fifty years ago.’

Esmond felt a genuine affinity; it was after this outing to Seddiqi Pasha’s that Esmond told her approvingly, ‘Georges is one of the better class of Copts. The family’s in tobacco. You know, those cigarettes I like. The family’s …’ he rolled his eyes and left a word hanging in the air, then whispered, ‘richissime! But Georges I think is the black sheep – an intellectual. Never married. Takes an independent line.’ He had asked him to keep an eye out for comparable volumes – in English and French. A kind of Egyptian Catholic, Ilia realised, with a stir of curiosity as well as relief, though she had made friends with some Muslims, her friend, Sadika, for example.

‘He was one of their leading writers, though nothing much has been appearing recently. Some journalism, reviews, that sort of thing. I said we’d stock the papers he wants if he gives us the gen. Has some real standing in some of the top literary circles, here. Part of a group who don’t hold with the current situation – with us being in charge, what? But he’s a fine fellow all the same. Very cultivated.’

![]()

When Georges looked at Ilia, smoothing his moustache, and offered his car and driver for the excursion to the garden where the true balsam once grew, she basked in his attraction, though he was far too old to be of any real interest to her. He was saying, in his deliberate English, with strong rolling Rs in the Arabic style, ‘They say that this balm was the finest – and the costliest – fragrant oil in the world. Hatshepsut, the woman pharaoh, who wore the sacred beard to fulfil her offices … my dear child, this is really true, why are you laughing? … it is no laughing matter. Her beard was a sign of her high status … she brought the art of distilling the leaves to Egypt from Jericho, where the plants were first planted and flourishing in the time of Suleiman. She used them to preserve her own body in immortality.’

![]()

The winter of 1949–50 brought beautiful weather, as Esmond noted in his diary:

Suddenly today it is quite gorgeous. Lovely sun, no clouds, but not ‘baking’. Shade temperature only 62 [degrees], but quite perfect to sit out. The visibility astonishing – objects such as the distant Sakhara pyramids which normally we can hardly see from the terrace are now clear as crystal. Delta looked quite lovely.

An outing was planned for soon after Christmas – the first staff party for the bookshop. The numbers grew larger than expected and Esmond drew on his old army expertise to arrange the transport: Ben Mendelssohn in one car, with Maisie, George and Labiba, the accountants, and Esmond’s secretary Pauline; we were to come in our car with Jamie and our driver Nasrallah, and another car would take several other members of staff – the other bookkeepers and the front-of-house manager. But there were still others who wanted to come. So, when Georges Dimitrino made his offer Esmond was happy to accept. Ilia could then travel in comfort in his car, with … maybe Sadika would like to come? If she could persuade that clubman Christopher to leave the city.

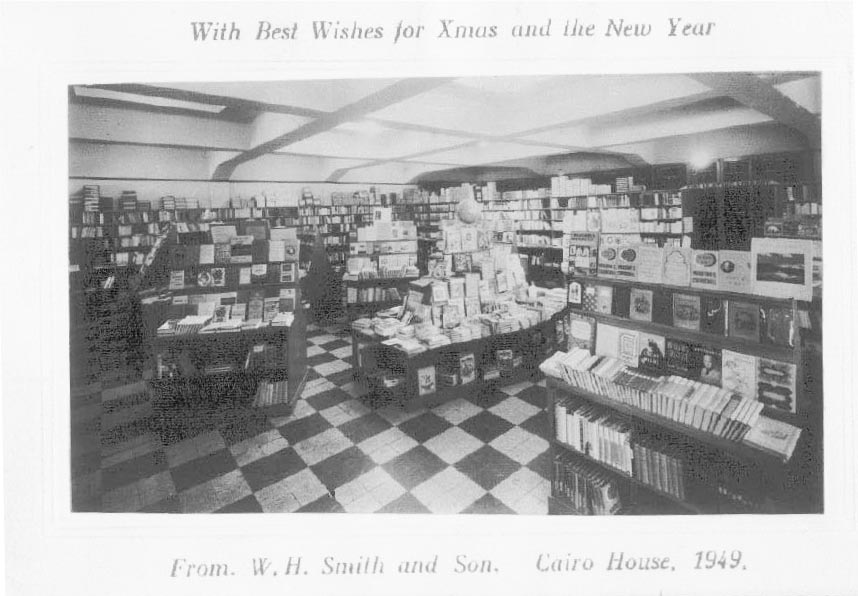

Christmas card from the bookshop, 1949.

Esmond was unfolding the map decisively: ‘Always keep to the original creases! Don’t force it any old how … that way you preserve its life. Respect a map. It’s a wonderful thing, a good map.’ He was in his element, plotting the route, the stops for revictualling, etc … ‘There’s a place near the barrage that’s been recommended … with facilities for you ladies … let’s hope up to snuff. We’ll take a picnic … this time of year, it’ll be very pleasant by the river. El Matareya might be a bit stifling but still bearable. We can take some refreshments and sit in the shade.’

Ilia was also growing excited at the prospect; she would wear the broderie anglaise tiered skirt she had made recently, trimmed with cerise and black ribbons, with a matching detail on her wide-brimmed white straw hat. It would keep her looking cool even if she weren’t feeling it. For her footwear, she’d choose her darker crimson sandals, with long laces tied around her ankles.

On this occasion, Esmond was encouraging, which took her by surprise, as he had forbidden her to go anywhere on her own and it seemed to her that going out with a man who was a stranger (and an Egyptian, besides) surely was more dangerous. She would have preferred her husband to warn her against travelling in the car with him, or utterly reject the very thought of it, but he seemed amused rather than jealous. She wanted to suggest Jamie rode with them but Esmond was adamant he should travel with the rest of the staff. ‘Dimitrino’s even older than me,’ Esmond had commented when she showed him the compact. ‘A pussy cat, I think!’ (It was a different matter, however, when she developed close ties with someone she had met on her own – especially an Italian.)

At the last moment she decided, if she couldn’t have Jamie near, she would take me with her, and Nanny. Our being with her would help to … she didn’t formulate what the future might hold, not exactly. But Esmond said Nanny should have the day off, as there were too many people piling in. So she told Nanny to put me in my best dress, the one she had smocked for me in green and blue thread following the lessons Nic, Michael Hornby’s wife, had given her before they left for Cairo.

Nanny adjusted my sun bonnet and fastened my white sandals and whispered, ‘Don’t forget, say a prayer for me to holy Mariam, peace be upon her.’

Surviving photographs reveal that pretty clothes didn’t suit me, but that I tried hard to live up to them, getting myself into dainty poses I’d been shown at my dancing class, that bumped up against the sturdiness of my limbs. When Ilia looked in on this class, arriving early to collect me, and I tried my hardest to do my pirouettes and curtseys to please her, she could not control the dismay and disappointment in her face: I was my father’s child, and none of her willowy grace had passed on to her first daughter, as it would, later, to my sister.

When I think of her, it is often in contrast to myself – she felt a kind of rivalry, envious of the chances Laura and I had, so very different from hers.

We took the lift down to the hall, and the car was waiting with Georges Dimitrino in the back. If he was startled to see me, the child as chaperone, he gave no sign, but put me beside him, between my mother and himself in the back seat, and we set off.

I can follow my child self sitting in the back seat of the car, between Georges Dimitrino smoking and my mother, with the driver at the wheel and another servant in the passenger seat in the front, who would serve the picnic from the basket in the boot of the car, as we made our way towards the garden and the shade of the old fig tree by the spring which watered the date tree that angels bent down to feed Mary, Joseph and the baby.

Ilia, apprehensive, began chattering.

‘You are very gay today,’ he said, ‘but I fear that even though it is January, it will still be a hot drive and the dust will spoil your beautiful dresses – yours and Marina’s.’

The car’s fan laboured, but a pleasant breeze came in through the car’s open windows, bringing the scent of donkeys and dried mud as we drove down the Nile and eastwards; very very few other cars. As we entered the quartier of El Matareya – Dimitrino explaining the route – we slowed down as the crowd grew denser.

‘Ragpickers, I am sorry.’ He spoke to the chauffeur in Arabic, clearly ordering him on, faster. ‘This is the only way to the shrine, through these wretches. But we shall be past them soon.’

I saw and my mother saw, glimpses cropped by the car windows’ frames, a busy populace crawling over heaps of rubbish, some children and many women with babies tightly wound to their bodies – on their backs or clasped to their breasts – going over the waste and sorting it, like worker bees from a hive, nuzzling the entrails of the body of the city to transform its leavings back into a new habitation, inspecting discarded materials of the recent war, clothing and scrap, leather trappings and horseshoes, canteens, kitchenware and pottery, old uniforms, other items of clothing and furnishings, throwing what they chose to keep into cloths which they bundled up into bags and loaded on to their shoulders alongside their offspring before dumping the contents in front of one of the traders, sitting under an awning by the side of the road.

Dimitrino banged on the driver’s seat, ‘Move, Move …’

‘I am trying, Monsieur Georges.’ The driver was hooting, intermittently at first, a polite cough, then sustained, hand on the horn.

The crowd on the side of the road were mostly men, with only a few women, and they were waiting for the women dredging the trash heaps to come down; they then opened the bundles the women laid down before them, and poked through them with a stick … lifting a garment here, knocking upright a piece of furniture there. Avoiding lice and fleas – and rats, Ilia realised. Their leathery faces, if not expressionless, were aggressively disdainful as they dropped a coin or two into the women’s hands. A lemonade vendor, squeezing the bright fruit from the pyramid on his cart and shaving a block of ice with a saw-toothed scraper, was doing fine business.

One of the women turned away from the press of the market, with a baby asleep on her back, and holding another child, a little older than me, by the hand. She came towards the car as we inched along and thrust a hand into the back, supplicating – it was unmistakable, that high-pitched cry of want. Ilia’s mother and her sisters had very little when Ilia was growing up, and she had seen many poorer than themselves in the stifling bassi in the old city of Bari, but never so destitute as these women and their babies knee-deep in the city’s leavings. She sensed the proximity of the woman, and all those other women at work in the rubbish; she intimated rodents and sores and lice and mange, and though she didn’t mean to or want to, though she wanted to be otherwise, she shrank back in horror. I squeezed myself closer to her, a whimper came out of my mouth. The driver said something, loudly, and dipping his hand into a box on the car floor under his feet, fetched out some loose change and called the woman over to his side of the car and dropped it in her curled, dry, cut-about hand.

‘There, there, don’t cry, little girls,’ said Dimitrino to my mother and me. ‘The fellahin are God’s children. I am a Christian, but in this regard, the ways of Islam are superior. We must give to the poor, always.’

In the low-slung dark grey car, flinching from the approach of beggarwomen at the windows whenever they drew to a slow speed, when the driver would reach into a box by his side on the floor of the car and fish out some coins to pass to the suppliant, Ilia remembered how another writer, Fausta Cialente, had said to her, with light flaring in her pale eyes, when they had met at a party, ‘I used to work for the British Army, all through the war here in Cairo, I used to talk on the radio to the soldiers – Italian prisoners of war – about poetry and novels. I was working for the English because at least they weren’t Fascists. They gave me the opportunity to talk to my fellow countrymen about how I thought about things, what I was trying to write myself. But now, what’s to be done? Levantinismo! All this …’ she had gestured around the party of elegant society women, Egyptians and Europeans and some Americans, in the airy room with the light falling through the slatted blinds at the hotel and slanting through the amber iced tea in their glasses. ‘Levantinismo!’ she’d repeated. ‘This supposed tolerant, mixed, wonderful society! We Europeans, we Levantines of the old world still enjoy conditions which we have crafted to our own advantage, which makes our life from day to day very sweet and easy. But I have seen, in all these years I have been in this country, the atrocious misery of this people, who are so gentle and pacific, so meek and mild. It is all destined to disappear. And it must.’ She looked at her new young acquaintance: ‘Soon,’ she said. ‘They’ – she gestured vaguely out of the windows – ‘won’t accept it – or us – for much longer.’

Ilia watched her lips close on her cigarette, and her eyes close in heavy-lidded warning, and she shivered at Fausta’s prophecy.

‘You will see, cara, what you will see.’

Later, after Fausta Cialente returned to Italy and produced her novel Ballata Levantina, a book drenched in its author’s sorrowful nostalgia at having left Egypt, one of her characters remarks on the wretches that crowded up against the cars, the shops, the bars and restaurants, the clubs, hotels, parks and gardens which were forbidden to them. The indolent, cynical Matteo tells the heroine, ‘But the peasant is Egypt, Daniela! It’s the fellah with his donkey and his bundle of clover, the same peasant of two thousand years ago. Nobody has done anything for him, for two thousand years.’ Then, prophetically in our present time of coronavirus, he goes on, ‘In fact, you’d think that epidemics and scarcity were devised just for him! And when they pass on the road, the pasha’s car and the peasant on his donkey, they don’t see each other … the two worlds brush past each other and never meet.’

Georges was soothing her – and me; he was setting up a distracting accompaniment of compliments and history, social banter and nostalgia … I was the butt of his flirting jokes: ‘You will grow up to be a heart-breaker, just like your mother … you are a very special little girl, anybody with eyes in their head can see that. But it’s hardly a surprise, is it, when you have a mother like yours …? Tell me, habibti, what do you like best to do … I am prepared to do anything to please you … for your mother’s sake. Look at your feet, are they like your mother’s? She has long slender toes, with the second digit longer than the big toe, always a sign of depths of feeling …’

Then with a wave at the scrolling view outside the car windows, he said,

‘All this part of Cairo used to be date palms … but the fellahin have been leaving the countryside and their oases and their fields and pouring into the city, swelling its size, obliterating its boundaries, strangling its natural beauty and its life … but let’s not dwell on the dark side. I am taking you – my dear Mrs Warner and dear Miss Warner – to a very ancient and mysterious place: you will feel the presence of the past there very strongly, the pure and holy past … not all this rubble and sprawl.’ He waved at the tangle of shacks and carts on the side of the road as they rolled slowly on.

The journey had probably taken only half an hour, but Ilia was almost asleep from the greasy slow hot air in the car and the strange flattery he was enveloping us in, her drowsiness mixed up with hallucinatory anticipation as to what Georges might do next. She was stiff with anxiety – was he going to let a hand fall on her thigh, was his support to her arm as she stepped out of the car more than courtesy, why was he giving the driver instructions in Arabic, now that we had finally arrived at a gate in a low white wall where bignonia, plumbago and bougainvillea were intertwined? A man in a white wool galabiyya, soft and clean, came out and greeted Georges, hand on heart, with a slight inclination, and then acknowledged us, his guests, dropping his head deeper, as the driver opened the trunk of the car, out of which he hauled a picnic basket and a broad parasol.

‘Come, we shall have some fruit and drink some water – they will quench us,’ said Georges. ‘I think we have reached here ahead of the others. Let’s hope they join us soon. I regret the discomfort of the journey, but now we have reached the destination of our pilgrimage, we shall go in and you will feel restored.’

Georges supervised the spreading of the rug on the ground in the shade, set out a small drum-like stool for my mother and himself, and we settled down to eat the oranges and sweets he handed round in boxes powdery with sugar, and began drinking sherbet from a thermos (it tickled me, fizzing up my nose).

‘The others will catch up with us soon,’ he said. ‘But they have to find their way.’

‘This is the fig tree of Pharaoh […] where, we are told, the Madonna often sat in its shade.’ Matteo Pagano, Veduta, 1549.

The holy tree was at first very disappointing, its main branch propped up on a crutch and sparse foliage sprouting from its withered limbs, its split seams trussed against further damage, some of its joints bandaged, with some feeble leaves giving signs of lingering survival. The trunk was so thickly knotted, gnarled and swollen as it sprawled, in its creaking cradle of branches, that it exuded antiquity as potently as the far more massive stone monuments of Luxor and the Sphinx; the tree was indeed very ancient and sphinx-like, an ancient and sacred beast, ravaged as a longtime chain-smoker or one of those shrivelled, clinker-like relics that would be lifted up high in a monstrance for the congregation to worship. It did not seem impossible, after all, that it had seen Mary and Joseph and the baby stop to rest under its shelter all those hundreds of years ago.

Or so Ilia was feeling, as the eerie charge of the place sent pleasurable quivers through her.

Where was Esmond, though? And Jamie? And the rest of the party? Ilia kept turning to look at the entrance to the shrine where I was playing with a little girl there … the daughter of the shrine’s custodian who was older than me, which I found exciting. She showed me some rabbits in a hutch, and we fed them stalks of something while Georges and my mother talked and laughed. Yet beneath the enjoyment Ilia felt as his pleasant melancholic conversation flowed around her, letting her into his ideas about books and art, about the writers he enjoyed reading, her sense of unease grew: what had happened to the staff? If they didn’t arrive soon, they would never reach the Nile barrage in time for lunch as planned.

Yet, as he confided to her how wracked he was by writer’s block, which he’d been suffering from for years, she felt a wish rise in her to help him, to inspire him. So the words would flow again – she could be his muse.

Then she called me to join them as they wandered through the garden to the little chapel at the end of it. The miraculous spring which an angel had raised beneath the tree to help the holy family was also meagre: paintings of the Flight into Egypt give an expectation of a gurgling stream, abundant enough for Mary to launder the baby’s swaddling clothes, and Joseph to dip a bowl to drink from and offer to Mary. But this muddy trickle, deep down in a cleft in the sandy rocky terrain, had almost dried up. Ilia looked into the depths and tried to think back to the images she knew. When Georges gently laid a hand on her upper arm, she jumped.

‘No need to be frightened,’ he said, and laughed.

Was she apprehensive that he would make advances (Sadika had warned her so clearly against them)? Were fears bubbling up from the depths that he might pin her against the wall in the chapel and press himself against her, his hard thing on her … did she cower? Did he kiss her, perhaps, when they were out of view inside the shrine, his lips brushing her forehead, lightly, and did he hold her steady till she looked back at him? Did she like the unexpected bristles of his moustache, and feel their impress long afterwards?

But the past won’t shape itself into a page-turning story, not for me. And I remember nothing of this kind – the memories of children can’t penetrate others’ feelings since we can hardly do that even with far more experience and understanding. We can’t go into the chapel with my mother and Georges Dimitrino any more than into the Malabar caves, however much the mystery of what happened there forms the fantasies that continue. I can’t eavesdrop in make-believe any longer.

All I can surmise – and the surmise has a basis in later events, as they were to become apparent – is that Ilia was changed, utterly changed by the attentions of the Cairene world and its climate of worldly flirtation, which she had never experienced before. Hers was an ugly-duckling tale: the gawkiness and height which had inspired that teasing pet name, la Giraffa, were now found utterly irresistible – Katharine Hepburn and Rita Hayworth and Greta Garbo were adored in Cairo, a city of cinemas and magazines, and after the war, Ingrid Bergman’s long limbs added to the transformation of the ideal female silhouette. Besides, the social codes that had ruled her life in Italy were dissolved – superannuated by a mode of approach that flouted her upbringing – when she had learned to avoid the aggression of some soldiers and to coax the inhibitions of others, like Esmond. But now, as a married woman, she was caught up on invisible currents like one of those most wanted, delicately feathered species of bird which were suspended on invisible laminae of heat in the summer light over the pools. It glimmered in her consciousness that she need not have married Esmond. That she was desirable in herself and could be so to others. The thought was only a feeble undercurrent at this point; of course this old Egyptian writer held out no real attraction to her and would not have ‘done’ anything, in spite of her (my) feverish anticipation, as, Cassandra-like, we both foresaw calamities which could not be averted.

But anyway, Dimitrino wasn’t the kind of man who’s interested in women … however much he lavished gifts on a young new arrival like Ilia.

Later, when she came to know him better, she realised why, but during that outing she was assailed by anticipation of … something improper, something terrible.

He had laughed at Ilia’s tremulous anticipation, because his donjuanismo was a façon de parler, a mask to idle away the time when he couldn’t write – or love.

My father had known that.

Flustered and hot, a group of staff arrived to join them; they had got lost and stuck in the milling crowd. They flopped down, a bit damp and dusty and crumpled, in the scant shade of the withered tree, fanning themselves and accepting the oranges with sighs of relief.

Jamie came over to her, with an orange in his hand. He offered it to her and caught her eye. She was glad of his clear anxiety that she’d been separated from the larger group. She felt a wave of tenderness towards him, his slight figure, his tousled head and sad eyes. He was her type; indeed he was.

At last, Esmond arrived, with his companions from his car. He was cross; he was hot and bothered from the traffic; his straw hat with the MCC ribbon looked limp. His smart new linen jacket which a local tailor had made for him was looking a bit tight, she noticed, across his shoulders.

She prayed he wouldn’t erupt.

‘Bloody map,’ he cursed, ‘and what a melee in that marketplace! Odi profanum, what? At least we’re all here and in one piece.’ He accepted a piece of orange from Ilia. ‘What have you been up to?’ he asked her. It was a rhetorical question. ‘Have you had the low-down from our learned friend?’

![]()

Nothing had happened, nothing. But something inside her felt different, as if she had grown another organ. The attentions Georges had shown her had lit a craving in her. It was a double craving, as it happens: for courtship and caresses, for admiration and for igniting manifest desire in others’ eyes, yes. But also, for a world of literature that lay beyond the bookshop. This she shared with Esmond: a subtle longing for the world angled through writing and writers. Georges Dimitrino was attractive to Ilia because he had written many books. She would begin to read what he thought about his country and his people, and she’d ask Esmond to track down Fausta’s stories in Italian. The mystique clung to the activity of writing, and they both passed on this feeling to Laura and me.

She left many journals behind, after she died, mostly written in Italian in her characterful spiky handwriting that is rebarbative to read. They are filled with recipes, notes on books she was reading, teaching notes about Italian literature for the classes she began giving, and lists of proverbs; also many, many pages about love affairs, mostly unsatisfactory – there was the one with Jamie Chantry which began when he was still uncertain whether he was gay and went on and off till he died. That was a sweet and precious and long-lasting amitié amoureuse. Another was very painful. But most of this happened later, after Cairo.

![]()