20

Shabti

Shabtis were buried with Egyptian pharaohs, queens, princesses, viziers, and their clerks and lesser officials. They are the labourers of the other world, who work on behalf of the deceased to meet their needs and provide for their comforts during eternity. Standing stiffly with arms tightly folded, figurines in wood, clay, stone and glazed turquoise faience, they’re surrogates – copies, dummies – of the dead man or woman, who was often a pharaoh or a queen, a dignitary, a scribe who was in the position of making ambitious arrangements for eternity. When demon overseers in the world on the other side of life put each soul to the hard labour of the corvée and other penalties, the shabti would magically assume the task, and with flails, hooks, seed baskets and other tools, carry out the necessary duties – and the substitution was satisfactory. The more powerful of the dead set up thirty-six overseers and 365 shabtis in their tombs, to ensure there was one at work on their behalf every day of the year. In earlier periods, miniature assemblies – showing fishponds and slaughterhouses, granaries and cattle pens, bakers’ ovens and butchers’ shambles – would provide the departed with complete scenarios of the work on their estates.

Ilia first saw an array of them in the National Museum in Cairo, which she liked to visit, often with a friend after Esmond, worried about unrest in the city, stopped her going out on her own. The magic spell, inscribed on their bodies, summons them to action: they must come to the call and say, ‘Here I am,’ and carry out all the tasks demanded of them. ‘Shabti’ is a play on the verb ‘to answer’, so shabtis answer and obey; they play-act someone else, and live their lives, speak their lines and fulfil orders to work well enough that the gods are pacified.

These answerers figure in the rituals of the dead, serving the several parts of their master or mistress: the ka-spirit is that part of a person that remains on earth and continues to need all the appurtenances of an easy life: bread and shelter, wine and music; the material body remains in the tomb with the ka, and has been mummified in oils, spices and perfumes so that it will withstand mortal corruption and thrill schoolchildren who in thousands of years will still be flocking to see them in London and Paris and Berlin. Besides these other parts of a person in the ancient Egyptian psychology are their names and their shadow, and, probably the most familiar aspect of all, the ba, or soul-bird, which flies away to the other world.

![]()

Serried ranks of these figurines were on view in a poky alcove in the Ashmolean in Oxford in the mid-1960s when I used to visit the museum, which is next to the Modern Languages building, the Taylorian, where I went to lectures; the shabtis have now been moved and are displayed more luminously, alongside model soul-houses and ships and other necessities, and they flank the pantheon of hybrid animal gods and goddesses – cobras, vultures, jackals, lions, hippos, cats, lionesses. Shabtis were run off assembly lines en masse in moulds, sometimes glazed, at other times painted, the artisan streaking in the stiff wigs with the same paint as the dark kilt, and rendering the feet with a splash of colour – reddish ochre for a male figure, paler sienna for the female; they do not have to be carefully made; they are dummies, but not dumb. They live in relation to the dead, trying to keep faith with them. Their time is a continuous now, as their raison d’être is to keep going and give respite to the subjects whom they substitute in the afterlife.

![]()

I’m fumbling towards an analogy with writing, or at least with the kind that Margaret Atwood describes as ‘Negotiating with the Dead’. In the case of a writer, a ghost is a kind of shabti (in French, the term for ghostwriter used to be nègre), who takes on their subject’s identity and labours in the public arena of this world on behalf of the other person. The ghostwriter steals with permission, taking up occupation of the story of someone who wants their story told but doesn’t know how to do it. In many ways, translators also write the book again, in another language, with permission to take over the words: Helen Lowe-Porter, who was Thomas Mann’s first translator into English, commented warmly that she acted as the ‘Would-be writer … Who refuses to let go of her translations until she feels she has written the books herself’.

As the last provides the cobbler with a template for a client’s foot, so tailors’ dummies model the measurements of a woman’s body – the dummy used to drape a dress or fit a jacket. They’re sometimes moulded to the customer’s shape – if the dummy is being used by a sarta, a professional dressmaker, the dummy might have an adaptable wire frame, to match different clients. Since Ilia had first set up the state-of-the-art Singer sewing machine she’d been given, she’d often muse that she’d like to have a tailor’s dummy to work on, but one didn’t come cheap.

Dummies also featured in the desert war Esmond lived through: artists helped create mock aerodromes to dupe German pilots, and built models of tanks so light that soldiers carried them above their heads like a papyrus canoe; camouflage experts like Joseph Gray also designed cut-out silhouettes of troops to be mustered in the sand as decoys. At the landings in the south of France in 1944, elaborate false plans, with decoys and mock soldiers, were mounted – and successfully distracted the enemy from the real site of the action.

A publisher’s dummy, on the other hand, is a mock-up of a book before publication, the same shape and size and quality of paper and boards, with the cover design and title and author of the book, but everything entirely blank inside. This kind of dummy used to be made – and are still by publishers who hold with book-making tradition, like the Folio Society. These blanks make perfect notebooks. Booksellers used to be presented with samples to encourage them to order the real book (a reverse of the shabti’s role, who acts to forestall any further demands on the dead man or woman whom he impersonates). As a bookseller, Esmond was always being presented with them, and my mother filled them with notes – recipes, guest lists, journals, lists of sayings and quotations and proverbs – after my father passed them on to her.

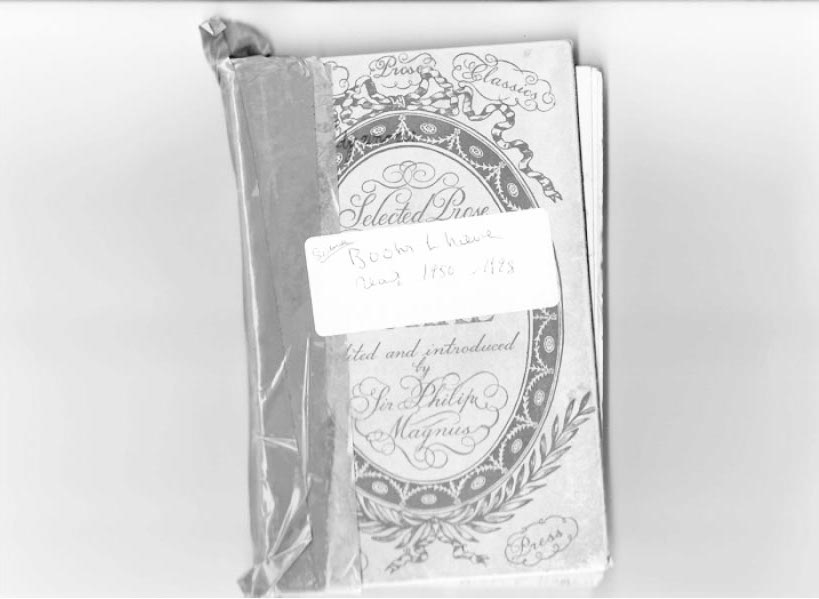

In a publisher’s dummy of a selection from Edmund Burke, Ilia has kept notes of her reading, 1950–98.

One of the earliest notebooks is a slim octavo volume, the title printed on the boards in a rococo cartouche and written in secretary-hand flourishes, with exuberant interlaced exhibitions of penmanship: Selected Prose of Edmund Burke, edited and introduced by Sir Philip Magnus (Falcon Press, no date). On this ornate front Ilia later stuck a label ‘Books I have read 1950–1998’. In front of the word ‘Books’, she has later inserted, with a kind of conscious sense of her achievement, the word, ‘Some’. The inside pages are thick creamy laid paper and are filled with Ilia’s distinctive, rather Gothic home-schooled handwriting – in pencil, mostly; to begin with she adds red biro, for outlining certain words and underlining others, and awarding three stars to her favourites.

In the very first entry she made in May 1950, in Cairo, at the age of 27, when she had been married almost six years, she copies this sentence from Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis: ‘But while I see that there is nothing wrong in what one does, I see that there is something wrong in what one becomes.’

There are a few Italian books: Neapolitan Gold is a 1947 account of the city by a Milanese journalist, Giuseppe Marotta, who had moved to Naples and made its ways his speciality (he’s the Italian precursor of Norman Lewis); there was enough curiosity in post-war Britain for the Hogarth Press to bring out a translation two years later, which Esmond had brought her from the shop. She also reads Iris Origo on Leopardi, and excerpts, in red biro, ‘Indifference and gaiety are the proper emotions, not only for a sage, but for anyone who has had any experience of human life, and the wit to profit by it.’

Indifference and gaiety: she is finding instructions in Leopardi’s thoughts.

I remember how she could rekindle a room filled with deathly dull ‘old sticks’ by putting on all her liveliness. She performed gaiety so it seemed real; she was masking the terrible, appalling anguish I found in her diaries.

Mostly, however, she was reading in English, and they are all recent books, which Esmond was bringing back from the shop for her as they arrived; they show his taste, but the responses are hers.

In January 1952, the month of the uprising and the burning of Cairo, she makes three entries, including Walter Baxter, Look Down in Mercy (a forgotten novel today, it’s a pioneering exploration of desire, with a gay encounter at its heart – Jamie and she discussed it, I feel sure). She awards it three stars.

In February 1952, when the bookshop has just been burned down and the troubles are continuing, she awards only one star to HRH the Duke of Windsor, A King’s Story. Over the summer that year, when the women, as my father put it, had been sent ahead to England, Ilia goes on reading – including Violet Trefusis’ recent memoirs, Don’t Look Round. She keeps making notes on passages that strike her: in Albert Camus, The Outsider, she finds these words: ‘Those who arouse love, even if it is disappointed, are princes who make the world worthwhile.’ And again, later, ‘Lying is not only saying what is not true … It is also … saying more than is true, in the case of the human heart, saying more than one feels.’

She loved Camus; she cried the night that his death was announced on the telly. I remember her sitting on the sofa, her face screwed up for someone she knew only through his writing.

She copies out these words from Charles Frazier, Cold Mountain (also awarded three stars): ‘she said, “Marrying a woman for her beauty makes no more sense than eating a bird for his singing.”’

Later, she gives three stars to Fausta Cialente’s Cortile a Cleopatra and adds, ‘a book which took me back … to the days of my innocence’ (Cialente returned to Italy after Nasser’s rise to power and translated Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet into Italian). Natalia Ginzburg is a constant favourite.

On the flyleaf of the back cover, Ilia (true to a lifetime of thrift, using every scrap), adds a declaration, in Italian, ‘This is a very inadequate notebook. Many books which I’ve read I haven’t registered here, such as for example, Marina’s books which I read when they had hardly been published.’

She is addressing me; she knows that after she has died, I will go through her things – alongside Laura, I’ll be her executor – and she wants me to know that she was reading, thinking, facing the world and the experiences it threw at her with discriminating thought based on wide reading. And she doesn’t want me to think that she left me out (I know she read me, and liked some of my books, though The Lost Father, the other one that’s mostly about her, gave her mixed feelings – as this one, the one I am now writing, would, too, if she could read it). ‘I don’t want to be exposed,’ she said, or rather cried out. ‘I don’t want people reading about me.’ I was crushed, I had wanted to please her. (A few years later, reading that book again in Italian, she told me she liked it better.)

Often personal writings like these share that impulse the dying Keats expresses so pungently in his last poem:

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d – see here it is –

I hold it towards you.

Ilia’s reading notes and her closing declaration aren’t filled with eerie menace, unlike Keats’s fierce challenge issued to those who come after him. Her script, which shows signs of the troubles that were afflicting her sight in her last years, holds out to me her living hand, elegant, fine-fingered, though by the 1990s gnarled with arthritis, but scented with the lemon she always kept by the kitchen sink, alongside the soap, to get rid of onion and garlicky and washing-up-glove rubbery smells; even in her closing days, her fingers were still crowned with long smooth carefully tended nails – filbert nails. They used to be varnished deep red (painted while watching the telly – never waste a moment, that was her way), adorned with the half-moon diamonds, the amethyst flower ring.

I am trying to be her shabti and answer to her ever-present ghost. Or so I think, as I sift through her notes and hear her vanished voice. Maybe I can whisper her lines on this side of life, to continue her being and register her experience by responding to the traces of her acts? If I take the hand she holds out from her self-archiving and note-taking can I interpret her and relate the story?

Unlike most friends of writers, she would eagerly read the books they wrote, but she gives Jamie Chantry’s first venture – Stash, a thriller – only one star. Thrillers weren’t to her taste anyway but she was disappointed again and again in friends’ efforts, even when, after my father died in 1982 and she moved to London, they had become part of her close circle of beaux and soupirants or even lovers.

Coming across her diaries of this period, all in Italian, the writing agitated and sometimes desperate, filled me with rage on her behalf against him. The scenes aren’t to be repeated here: her ghost would shudder at the memory of those times of deep unhappiness. Yet she didn’t destroy these notebooks, several volumes of them, brimming with more hopes of love.

The sense that she had found herself too late after the marriage to Esmond grew and grew. One year, she sent me a birthday card, with the message, ‘How lucky you are to be young!’

![]()

It has taken me over a decade since my mother died to look through her clothes again. After my sister and I emptied her wardrobes and her chests of drawers, I kept all the outfits she made herself, from the 1940s in Cairo to the 1960s and 1970s in Cambridge. Because I no longer sew, words that were familiar in her vocabulary are no longer in use in mine or have acquired a different meaning.

For example, basting; the loose stitches used for the initial stages of making of a dress, hardly in use any more, for the word usually now describes moistening a roast with its own juices to stop it drying out in the oven. Selvedge: the sealed end of a roll of material which will not unravel and cannot be pulled out of shape or draped to fall in another way besides the straight, unlike fabric cut on the bias which can then, my mother showed me, be fashioned to fall in loose folds, or stretched to fit a longer length of material to make a frill or a ruffle.

How such terms lend themselves to metaphor: basting for the shallow safety of the unexamined love, for the flight from scrutiny and close attention; selvedge for the limit, which is a kind of safety, a holding place, a fixed address; and bias – to think that the concept of bias comes from this material property of fabric, that it will lend itself to a shape by clinging, by slanting, by accommodation.

![]()

She holds out her hand to me through the notebooks she did not destroy, the reading notes I found on her bedside table after she had been taken to the hospital for the last time, and she calls to me to answer, to witness the arc of her life.

And yet, when a shabti toils in the underworld, he or she is also acting to divert demons from the proper subject of their purposes; writings may also become part of a strategy to disguise the truth – not intentionally, but as a consequence of wishfulness. A memoir like this one, which needs must be unreliable, since it is not possible to know your parents or their lives and yours before the age of six, substitutes for what really happened and who they really were; its work on their behalf inevitably misremembers or misrepresents, or, at best, embellishes, failing to set out what really took place.