Lillian Hellman

Lillian Hellman has long been known as a moral force, almost an institution of conscience for the rest of us—but my view is that her influence, and her help to us, derive rather from something larger: the picture she gives of a life force.

It is the complexity of this organism that stuns and quickens us. Energy, gifts put to work, anger, wit, potent sexuality, wild generosity, a laugh that can split your eardrums, fire in every action, drama in every anecdote, a ferocious sense of justice, personal loyalty raised to the power of passion, fantastic legs and easily turned ankles, smart clothes, a strong stomach, an affinity with the mothering sea, vanity but scorn of all conceit, love of money and gladness in parting with it, a hidden religious streak but an open hatred of piety, a yearning for compliments but a loathing for flattery, fine cookery, a smashing style in speech and manners, unflagging curiosity, fully liberated female aggressiveness when it is needed yet a whiff, now and then, of old-fashioned feminine masochism, fear however of nothing but being afraid, prankishness, flirtatious eyes, a libertine spirit, Puritanism, rebelliousness….

Rebelliousness above all. Rebelliousness is an essence of her vitality—that creative sort of dissatisfaction which shouts out, “Life ought to be better than this!” Every great artist is a rebel. The maker’s search for new forms—for ways of testing the givens—is in her a fierce rebellion against what has been accepted and acclaimed and taken for granted. And a deep, deep rebellious anger against the great cheat of human existence, which is death, feeds her love of life and gives bite to her enjoyment of every minute of it. This rebelliousness, this anger, Lillian Hellman has in unusually great measure, and they are at the heart of the complex vibrancy we feel in her.

But all the attributes I have listed are only the beginnings of her variousness. She has experienced so much! She has had an abortion. She has been analyzed. She has been, and still is, an ambulatory chimney. She drinks her whiskey neat. She has been married and divorced. She has picked up vast amounts of higgledy-piggledy learning, such as how to decapitate a snapping turtle, and I understand that as soon as she completes her dissertation, said to be startlingly rich in research, she will have earned the degree of Doctor of Carnal Knowledge. This is in spite of the fact that during a long black period of American history she imposed celibacy on herself. She will admit, if pressed, that she was the sweetest-smelling baby in New Orleans. As a child she knew gangsters and whores. She has been a liberated woman ever since she played hooky from grade school and perched with her fantasies in the hidden fig tree in the yard of her aunts’ boardinghouse. She is so liberated that she is not at all afraid of the kitchen. She can pluck and cook a goose, and her spaghetti with clam sauce begs belief. She can use an embroidery hoop. She knows how to use a gun. She cares with a passion whether bedsheets are clean. She grows the most amazing roses which are widely thought to be homosexual. She speaks very loud to foreigners, believing the language barrier can be pierced with decibels. She scarfs her food with splendid animal relish, and I can tell you that she has not vomited since May 23, 1952. She must have caught several thousand fish by now, yet she still squeals like a child when she boats a strong blue. I know no living human being whom so many people consider to be their one best friend.

She is not perfect. Her chromosomes took a little nap when they should have been giving her a sense of direction. “We can’t be over Providence,” she said, flying up here this morning. “Isn’t Providence to the south of Martha’s Vineyard?”

I told her it was to the northwest of the Vineyard.

“But when you drive to New York, you go through Providence,” she said, “and New York is to the south of us.”

I said that the only way to drive directly to New York from Martha’s Vineyard would be to drive on water, and that I could think of only one person in history who might have been able to do that.

She said, “You mean Jews can’t drive to New York?”

God gave her a gift of an ear for every voice but her own, and when she tries to disguise that voice on the telephone, as she sometimes does, the pure Hellman sound comes ringing through the ruse. “No, Miss Hellman is not here,” the voice will say. “Miss Hellman is out.” The only thing you can be sure of is that Miss Hellman is in.

She is, I believe, the only National Book Award winner who can claim to have had a father who cured his own case of hemorrhoids with generous applications to them of Colgate’s toothpaste.

I am fairly certain that she is the only member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, female or male, who has thwarted an attempted rape by staging a fit of sneezing.

She also has the distinction of being the only author at or near the summit of the best-seller lists who has publicly stated that she has always wanted to go to bed with an orangutan.

She is surely the only employee of Sam Goldwyn who ever refused to attend two conferences with the great mogul because of being too busy rolling condoms. (Perhaps I should add, in case you are wondering why this activity was taking place, that it was in the interest of a practical joke.)

Miss Hellman has changed the lives of many people, as teacher or exemplar or scold, and a few people have changed hers. Among these, two stand out.

The first is Sophronia, her wet nurse and the companion of her childhood, and, her father would say, the only control she ever recognized. “Oh, Sophronia, it’s you I want back always,” Miss Hellman cries out in one of her books. As a kind of pledge of her debt to Sophronia, Miss Hellman sent her the first salary check she ever earned. There is a photograph of this remarkable figure of pride in An Unfinished Woman, and, looking at it, one sees the force of what Miss Hellman writes: “She was an angry woman, and she gave me anger, an uncomfortable, dangerous, and often useful gift.” Once, when the child Lillian had seen her father get into a cab with a pretty woman not her mother, Sophronia counseled keeping her mouth shut, saying, “Don’t go through life making trouble for people.” We all know the stern and dazzling resonance of that advice in Miss Hellman’s appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee in Joe McCarthy’s time.

The other person was Dashiell Hammett. With that handsome, sharp-minded, and committed man she had a relationship, off and on, for over thirty years, one which, as she has said, often had “a ragging argumentative tone,” but which had “the deep pleasure of continuing interest” and grew and grew into “a passionate affection.” Hammett was—and he remains to this day—her conscience. He was her artistic conscience, as ruthless with her as he was with himself in his own work, for ten of her twelve plays. She still makes many a decision by asking herself, sometimes out loud: What would Dash have wanted me to do about this? Death took Hammett and became her enemy.

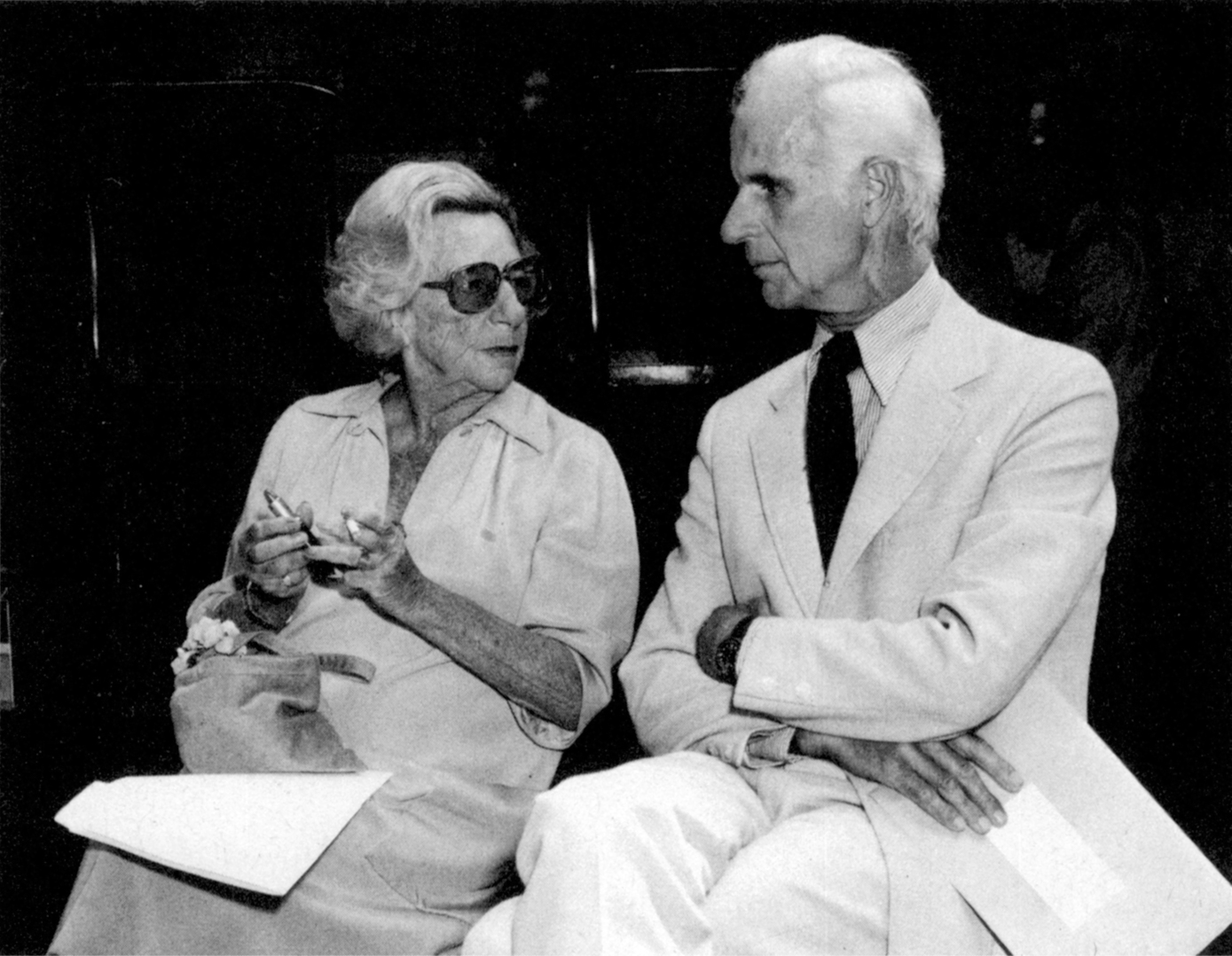

HELLMAN AND HERSEY AT THE MACDOWELL COLONY

“Anger, an uncomfortable, dangerous, and often useful gift.”

I have spoken, she herself has spoken, of a religious streak in her. It is hard, perhaps dangerous, to trace or describe it. She is profoundly yet also skeptically Jewish—more in culture and sensibility, obviously, than in faith. She tells of an indiscriminate religiosity that her mother had, dropping in on any house of worship. Hers is certainly not like that—yet there is a weird ecumenical something-or-other going here. She writes somewhere of Bohemia bumping into Calvin in her. Calvin! When anything seems unspeakable to her, she will shout “Oy!” and cross herself. When all her beliefs and rituals, serious and playful, are rendered down to their pure state, just this remains: she insists on decency in human transactions.

This places her—a lonely, lonely figure—at the nowhere crossroads of all religions and all politics.

She is a moral force, but take a firm grip on your hat!—for the moment will come when the force, operating at high pitch, will suddenly go up in smoke before your eyes, and in its place will stand pure caprice. This is sometimes a mischievous thirteen-year-old girl.

Nothing gives this girl greater pleasure than to be shocking. She knows I was born in China and love and respect the Chinese, so whenever I’m around, her universe is suddenly thronged with Chinks. Niggers, kikes, and idiot WASPs crowd tales told to prim folks. Bad food—even if it is bad lox and bagels—is always “goy dreck.” She incessantly offers TLs—“trade lasts,” compliments spoken by absent parties and offered on a barter basis (there was one in The Children’s Hour)—but again, be wary: what she gives in exchange often has an ironic barb in it.

If she says, “Forgive me,” my advice is to back away. This is a signal for the final blunt blow in an argument. In Vineyard Haven, she and my wife and I have a mutual neighbor, a willful lady whom I shall call, as Miss Hellman calls all women who should be nameless or whose names she has forgotten, Mrs. Gigglewitz. Miss Hellman met Mrs. Gigglewitz downtown one day, and the latter began to complain about the noise certain neighborhood dogs made. One of them, she said, was that awful Hersey dog. The fact of the matter was that our dog could bark—but seldom did. Miss Hellman’s powerful senses of loyalty and justice were instantly mobilized.

“I don’t think you hear the Hersey dog,” she said.

“Oh, yes,” the woman blithely said. “It makes a hell of a racket every morning.”

“No,” Miss Hellman said, “their dog is exceptionally quiet.”

“Quiet? It barks all day.”

“I think you’re mistaken.” Any ear but Mrs. Gigglewitz’s would have heard the sharpness in the voice.

“I’m not mistaken. It makes a terrible racket.”

“Forgive me, Mrs. Gigglewitz,” Miss Hellman then said. “I happen to know that the Hersey dog has been operated on to have its vocal cords removed.”

Miss Hellman’s powers of invention are fed by her remarkable memory and her ravenous curiosity. Her father once said she lived “within a question mark.” She defines culture as “applied curiosity.” She is always on what she calls “the find-out kick.” How long is that boat? How was this cooked? What year was that? All this questioning is part of her extended youthfulness. More than three decades ago she wrote, and it is still as fresh in her as ever, “If I did not hope to grow, I would not hope to live.”

We must come back around the circle now to the rebelliousness, the life-force anger, with which Miss Hellman does live, still growing every day. There was a year of sharp turn toward rebelliousness in her, when she was thirteen or fourteen. By the late nineteen-thirties or early forties, she had realized that no political party would be able to contain this quality of hers. Yet the pepper in her psyche—her touchiness, her hatred of being physically pushed even by accident, her out-of-control anger whenever she feels she has been dealt with unjustly—all have contributed in the end to her being radically political while essentially remaining outside formal politics. Radically, I mean, in the sense of “at the root.” She cuts through all ideologies to their taproot: to the decency their adherents universally profess but almost never deliver. “Since when,” she has written, “do you have to agree with people to defend them from injustice?” Her response to McCarthyism was not ideological, it was “I will not do this indecent thing. Go jump in the lake.” Richard Nixon has testified under oath that her Committee for Public Justice frightened J. Edgar Hoover into discontinuing illegal wiretaps. How? By shaming.

In her plays, in her writings out of memory, above all in her juicy, resonant, headlong, passionate self, Lillian Hellman gives us glimpses of all the possibilities of life on this mixed-up earth. In return we can only thank her, honor her, and try to live as wholeheartedly as she does.

She and I share a love of the sea. We fish often together. Coming back in around West Chop in the evening light I sometimes see her standing by the starboard coaming looking across the water. All anger is calm in her then. But there is an intensity in her gaze, almost as if she could see things hidden from the rest of us. What is it? Can she see the years in the waves?

Presentation of the MacDowell Medal, the MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, New Hampshire, August 15, 1976; “Lillian Hellman, Rebel,” New Republic, September 18, 1976.