THE CREATIVE PINNACLES: INDIVIDUATION AND INTERDEPENDENCE

Individuation is Carl Jung’s way of describing self-actualization, or the process of living authentically while expanding the boundaries of what we allow ourselves to perceive and experience. Through using both our outer and inner senses, we are able to tap more deeply the realm of unlimited creative possibility.

Mark Levy of Magdalena at the Ivy Hotel in Baltimore recalls, “From my first day as a cook until I turned 30, everything I cooked was inspired by others. Grant Achatz’s book [Alinea] came out, and I’d try making mozzarella using a CO2 canister and chasing down different spices. Then I started asking myself, ‘What is this chemical?’ and then, ‘Do I really want that in my food?’”

“Finally, I started asking myself, ‘What do I like?’” he says. “Since that time, I’ve been trusting and cooking what I like. As a cook, a lot of times you get beaten down, or you turn into a robot—and no one ever develops your confidence in what you’re doing. So to really start believing in what I know or what I feel is right—it was probably the most important thing I had to learn. Now, I will buy books by people with similar views, or who know something I specifically want to learn about.”

Finger Lakes chef-restaurateur-master sommelier Christopher Bates of FLX Wienery and FLX Table has long kept a close eye on what is trending in food, so much so that his former dining room at the Hotel Fauchère in tiny Milford, Pennsylvania, was serving foraged foods on slate even before some Manhattan restaurants started doing likewise. “Food is so good and pretty now—everyone wants to eat off a broken barn door now, and it is hard not to want that,” he acknowledges. “But at some point you have to resist [the trends] and come up with your own ideas and walk your own path. Today, I have to look away from everyone else.…I see the Nordic plating and it is so cool and beautiful, but I need to do my own thing and not try to keep up with the Joneses. I’d rather come up with what is next versus [imitating] what is happening now.”

“Culinary inspiration is funny,” Bates continues. “Loic [Leperlier, of the Point resort in Saranac Lake, New York] and I were talking about it, and he explained that he didn’t look at cookbooks as much anymore. I try not to keep up with stuff anymore, either, so I got what he was saying. These were things I was thinking five years ago. Today, I want my inspiration to come from my life and my interests.” Those personal inspirations seem to be resonating with others; FLX Table was named the country’s best new restaurant in a 2017 USA Today 10Best Readers’ Choice poll.

BE YOURSELF.

—ERIC RIPERT, Le Bernardin (New York City)

Think carefully about what makes you special and different from everyone else.

—MICHAEL ANTHONY, Gramercy Tavern and Untitled (New York City)

In the forest, you can’t see the individual trees.… It’s important to ask yourself the question: How are you unique and different?… Being creative reflects an evolution of who you are as a person.… The door is currently wide open to different expressions.

—EMILY LUCHETTI, chief pastry officer,

The Cavalier, Marlowe, and Park Tavern (San Francisco)

Curtis Duffy of Chicago’s Grace recognizes the difference in his cooking. “We can do a lot of crazy things, but it has to fit the big picture of what I’m trying to achieve,” he says. “It has to fit the identity. As a young cook, I could pick out Charlie Trotter’s dishes or Thomas Keller’s dishes anywhere. So I always wanted to have that kind of identity, too,” he says. “People who know me personally would describe my cuisine as a personality cuisine. It’s foods that I enjoy cooking with and eating when they’re in season—it’s foods that make me happy. I would never put shrimp or green bell peppers on my menu, because these are things that I don’t eat—I’m allergic to shrimp, and I don’t like the flavor of green peppers. I veer away from heat [i.e., capsicum] altogether. I can appreciate it, but I don’t cook with it.”

As a pastry chef, I am very focused on who I am and what I want to do. I pay attention to trends, but I’m not a copycat. I JUST DO ME.

—TAIESHA MARTIN, pastry chef, Glenmere Mansion (Chester, New York)

San Francisco’s Emily Luchetti shares that her MBTI (Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a leading personality test) type is ESTJ (Extroverted, Sensing, Thinking, Judging), which means she likes “rules and making decisions.…“But there’s no recipe for an ideal pastry chef,” she acknowledges. “Why can some people cook? Why can some people be creative? You can learn technique, and to train your palate, but I don’t think you can teach creativity. You just have to take it all in—all you study, all you read, all you taste—and then it starts churning inside you. And, if you’re lucky, it comes out—as a replication, or as an adaptation, or as something completely original.”

Animal’s Jon Shook and Vinny Dotolo recall that at Bastide, Ludo Lefebvre, their partner in Trois Mec was “doing elBulli stuff.…Now, he’s cooking over an open fire. He really brings all of it together,” they told us. “That’s what you do as a chef: You’re telling your story.”

“We’re telling a story through all of our restaurants—all of our life experiences, all of the things we learned about food,” they continued. “Chefs used to do it through a tasting menu, and now I think they’re doing it through multiple restaurants. Many chefs now have five restaurants—once they hit something, they’re trying to find that other thing where they can have that creative outlet. You can only stuff so much into one place. We couldn’t pack a seafood concept, an Italian concept, and Animal into one thing. You need a release.”

You have to write your own story. Everyone else’s is taken.…

Have something to say? Go for it. REMAIN TRUE TO YOURSELF.

—LIOR LEV SERCARZ, La Boîte (New York City)

Patrick O’Connell believes every chef can carve out his or her own niche. “I think the creative process and that energy can be exhibited in anything, anywhere. I like the Blue Ocean idea [as explained in the bestselling book Blue Ocean Strategy by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne] that if you differentiate yourself clearly in every possible way, you won’t be chasing after the same goals that everyone else is—you will carve out a [niche for yourself].

“It’s an intriguing book,” he continues. “We had a speaker talk about it at one of our international Relais & Châteaux meetings. The idea is that you don’t go after what your competition is going after. You go after what is totally authentic to you. And ultimately there won’t be any competition—because we’re all unique in who we are.”

José Andrés on Creativity

Creativity to me is anything that allows you to solve a problem. It doesn’t matter how big or small—but it solves a need, challenge, or dilemma in a successful way. So you could argue that behind every creative process there needs to be a question or a challenge. It could even be one you invent, like, “I want to create a cauliflower [that] is frozen on the outside and creamy on the inside!” (See here.)

Despite coming up with the idea for my salt-air margarita there, in general, it is hard to be creative on a beach. Creativity can happen at any time—and I think creativity happens in the most unexpected ways in daily life. But it’s more likely that I’ll be working, not on the beach in the Caribbean.

You need to be aware of who you are and how you relate to ingredients. For inspiration, you can go to your main sources and look for new ingredients or equipment. Sometimes you might get inspired by the farmers’ market or fishermen.

True creators are challenged by moving away from their comfort zones. Sometimes I need to move away from my normal forms of inspiration to be inspired. Working with Dale Chihuly blowing glass served as a source of inspiration for the first-ever caramelized olive oil, based on how Dale works with glass.…The caramelized olive oil started out as one bite then became part of a salad that developed into the Dale Chihuly, Garden and Glass Salad [in which the olive oil looks like it has been dipped in glass]. This was my homage to him.

Knowledge alone is just a doorway to creativity. Knowledge alone does not make a creative person, system, or organization. You need to have the right knowledge to apply to improve something. Creating something new is what makes your creative process powerful.

What I am saying is that you have to move away from your comfort zone to discover the true potential of your creativity and the creative process.

We use creativity on my team to create new amazing techniques and [figure out ways of] applying them. We do something new with techniques that has not been done before, and will use them in our restaurants to push the envelope.

Our office is filled with sofas to make everyone comfortable and not waste time. We use everything from text messages, Evernote, email—or I will tweet or post something on Instagram. I don’t post things as To Do’s for my team—I post them for inspiration. I want them to get excited because they see [what I’m thinking about], and what I see as worth getting inspired about. I want to create the desire to experiment and learn.

Creativity = knowledge + organization + desire + experimentation + learning

To people who complain about “too much” creativity, I say, “Who are you to judge?” Without Galileo [who has been called the father of science], where would humanity be?

You always need creativity and creative people to move humanity forward. You need those who push and those who follow. It is OK to make good paella or a good crepe. That is also part of my life. More important than creativity is truly good execution. If I were to make the best soup dumpling ever, I would not consider it creative—I would simply consider it a great dish.

Creativity is that top layer of people pushing, and society has always evolved from those efforts.

At the end of the day, CREATIVITY IS WHAT MAKES HUMANITY GREAT.

José Andrés at Beefsteak (top), holding the glass vases he blew with artist Dale Chihuly (middle), and planting tomatoes in his garden (bottom)

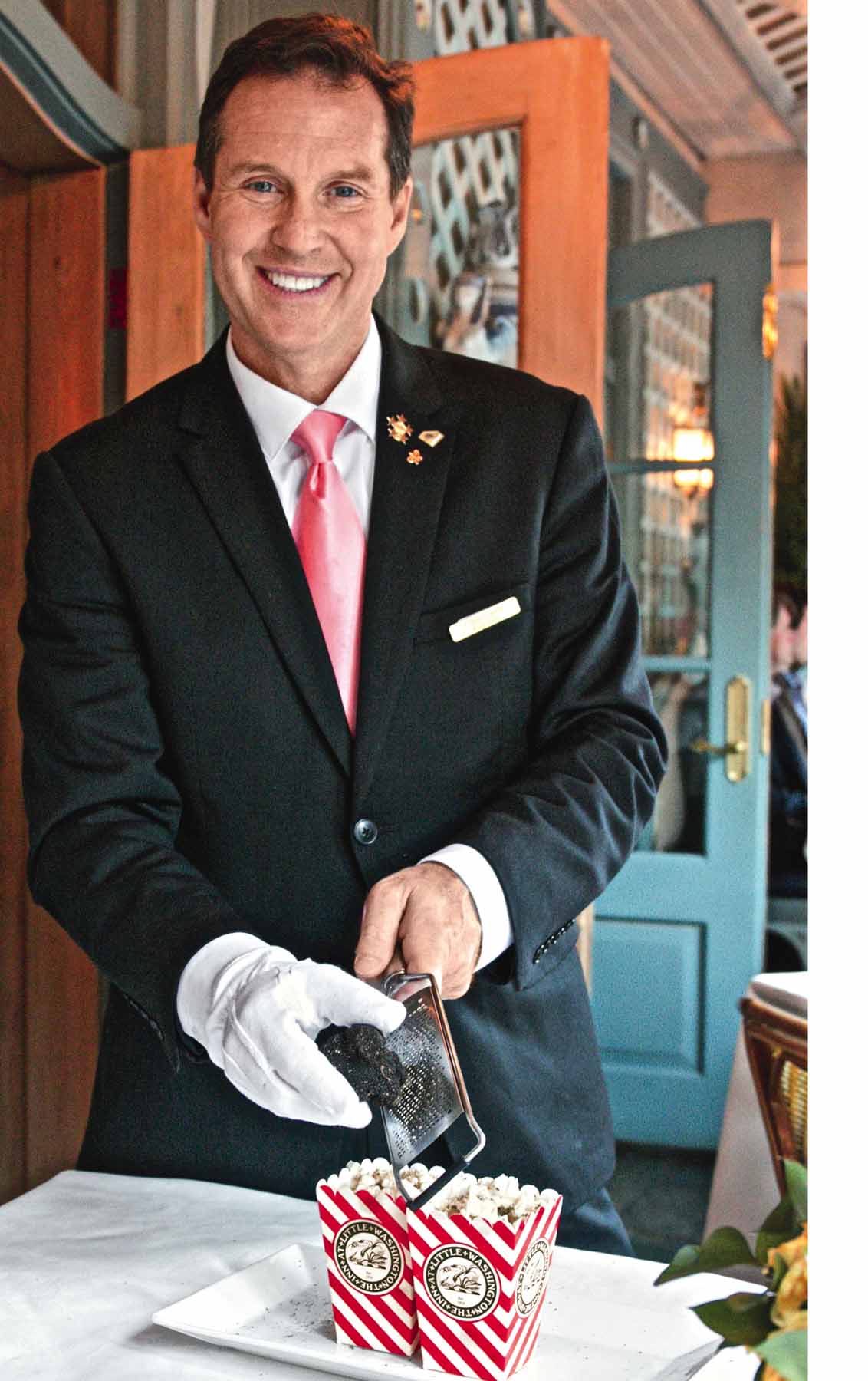

THE X FACTOR AT THE INN AT LITTLE WASHINGTON

The Inn at Little Washington in Virginia constantly delights through thoughtfully considered touches that leverage the X Factor—from shaving truffles tableside onto popcorn in old-fashioned red-and-white-striped movie popcorn boxes emblazoned with the Inn’s logo, to wheeling their cheeses through their elegant dining room on a mooing cow named Faira.

The Inn at Little Washington

DAMON BAEHREL TAKES CREATIVE CONTROL—TO AN EXTREME

Chefs love having control, but Damon Baehrel lives for it—and with it. He does not wait for produce deliveries, hope his line cook or dishwasher shows up, or worry that his ingredients are at their peak. Instead, he harvests virtually everything (with the exception of meat and fish) on his 12-acre property himself, prepares everything himself, cooks everything himself, serves everything himself, and even cleans up afterward at his tiny 20-seat eponymous restaurant in Earlton, New York, which the New Yorker referred to as the Most Exclusive Restaurant in America.

Two years, four months, and 14 days after our first inquiry about a reservation, we were able to experience Damon Baehrel—the man and the restaurant—for ourselves. Our departure following our first visits to other extraordinary properties had moved us to tears (e.g., the Inn at Little Washington, the Point). However, our departure from Damon Baehrel prompted pure, stunned silence: If the extraordinary, handcrafted meal we’d experienced hadn’t been a mirage, was it a miracle?

Disliking the metallic flavors imparted by cooking in pots and pans, Baehrel says he cooks on stones for more of a mineral flavor. After noticing deer eating tree bark for just a few weeks in the early spring, he tasted it and found it salty—and started using it as a salt substitute in preparations. Baehrel discovered acorn oil—which he uses in lieu of butter, thanks to its buttery flavor—by accident. After paving his driveway because of the New York State code, he kept noticing oil spots on his driveway. One day he happened to notice that the car tires were crushing the acorns and creating the oil spots. He then started harvesting the acorns for oil. On his cheese plate, each individual cheese had its own garnish, from a single celery leaf to a half-inch of fennel frond.

That’s not to say there are no hints of luxury. However, the flavor of truffles comes not from truffles themselves but—surprise!—from dried, powdered, and reconstituted Louisiana Greens, an heirloom variety of green-skinned eggplant that Baehrel discovered happens to have a flavor reminiscent of them, when it’s not cooked out or canceled out by dairy. And we were also served tiny savory acorn flour cones, reminiscent of Thomas Keller’s salmon cornets, presented in a hole in an oak log, which Baehrel says he’s been making for catering events since 1986.

In his cookbook Native Harvest, he details how he even makes or cures his own:

• acidifiers: using unripened green strawberries, or sumac berries brined in sumac powder

• breads: from scratch from homemade flours and yeast from local wild grapes on the property, and baked on bluestone slabs; served on black walnut log “plates”

• broths: from branches, e.g., ironwood, maple wood, eparch wood

• cheeses (aged): dozens of varieties, including blue cheese made from cow’s milk, one made from a mix of sheep and goat milk curdled with fresh stinging nettles; as well as a cow’s and sheep milk cheese (which used fermented cauliflower juice to curdle it)

Damon Baehrel

• coffee: fermented mashed acorn and hickory nut “coffee,” sweetened with stevia

• flours: made from acorns, beech nut, cattail, cedar (which is naturally bitter, so it takes an entire year to rinse sufficiently to eliminate the bitterness and make it palatable), clover, dandelion, goldenrod, pine tree bark, wild clover

• flowers: marigolds, pine flowers, wild sweet clover flowers; thickened with wild violet leaves and stems

• greens: lambs quarters, which many consider a weed, are used as greens in multiple dishes (The ones he sent us home with got tossed into pasta in lieu of spinach.)

• mushrooms: wild oyster mushrooms; wild honey mushrooms; wood ear (birch polypore); his property has 140 to 150 different varieties of mushrooms, about half of which he says are edible and half of those delicious; some must be slow-cooked for 55 hours to soften. (He has been working land for over 30 years and seeds logs for mushroom harvesting.)

• oils: acorn oil (with a toasty, buttery flavor), butternut oils, hickory nut oil, grape seed oil, hemlock needle oil

• pepper: apple bark “pepper,” hickory shag bark “pepper”

• pungents: a green powder that turned out to be lichen that had been soaked in water and baked, which tasted onion-y; wild onion powder; garlic scape powder; chopped wild onions

• saps: sycamore (incredibly fresh-tasting water, as if you’d cupped your hands for a sip from a pristine stream)

• seasonings: pickled baby maple leaf powder (mildly spicy); Black Krim tomato powder; wild fennel powder; caraway and marjoram powder, beechnut powder, flax, cedar berries, spruce and pine shoots; (truffle-like) green eggplant powder

• slushes/ices: wild grapes sweetened with unripened grape syrup filled with a tiny cluster of wild maple seeds cooked in homemade maple sap “sugar”

• sweeteners: stevia; unripened wild grape syrup made from seven different types of wild grapes

• vegetables: baked wild black burdock root, tiny wild carrots, sliced daylily tubers (rather like potatoes), kohlrabi (kohlrabi cooked in a homemade “saffron“ broth made from smoked wild bergamot flowers, and a sauce made from wild brassica roots cooked in the soil they were with, giving a smoky briny effect; wild crispy baked sunflower roots completed the dish

• vinegars: green strawberry vinegar; onion vinegar, chard root vinegar and aged tomato vinegar; makes four or five dozen different vinegars

The housemade cheese plate at Damon Baehrel

EVOLVING FROM DEPENDENCE TO INDEPENDENCE TO INTERDEPENDENCE

We’ve already learned that creativity is enhanced by happiness. Happiness, in turn, is enhanced by perceived social support, such as being part of a team.

The best technique for brainstorming is to first work alone to generate ideas, then to pool ideas with others and debate them.

—MICHAEL GELB, author of How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci

The image of the solo creative genius—like a solitary Michelangelo on his back painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel over four years—is becoming rarer, as the realization of the power of collaboration grows.

Through self-mastery, you grow and evolve from dependence to independence as a cook. But moving from independence to interdependence has taken many of the most creative restaurant kitchens in America to creativity of an even higher order (see sidebar here) by leveraging the power of teamwork. Witness all the ways leading chefs have been coming together to address social problems, whether it’s José Andrés’s World Central Kitchen; Dan Barber’s wastED (which showcased how discarded food could be transformed into exquisite cuisine); Rick Bayless’s Frontera Farmer Foundation; Daniel Boulud’s co-leadership of Citymeals on Wheels; Ann Cooper’s Chef Ann Foundation; Michel Nischan’s Wholesome Wave; Daniel Patterson and Roy Choi’s LocoL; Jessamyn Rodriguez’s Harlem-based Hot Bread Kitchen; Michael Solomonov’s Rooster Soup; Bill Telepan’s Wellness in the Schools; or Marc Vetri’s Vetri Community Partnership—to name just a few.

If you give a good idea to a mediocre team, they will screw it up. If you give a mediocre idea to a brilliant team, they will either fix it or throw it away and come up with something better.… Find, develop, and support good people, and they in turn will find, develop, and own good ideas.”

—ED CATMULL, cofounder of Pixar, in his book, Creativity, Inc.

On a daily basis in their kitchens, chefs are learning and then teaching the power of collaborative creativity. “We have quite the following for our family meal [the kitchen staff’s meal before dinner service],” says Jeremy Fox of Rustic Canyon. “Everyone [in the kitchen] makes it one day a week and they have a budget and they get a lot of recognition for it. I will post pictures of it on Instagram and sometimes it seems like the only thing I post that people care about.”

He continues, “Every other day, the cooks have to cook what I want them to cook—but this is the day they can cook anything they want to cook, and can order what they want. Since they know what day they are cooking, they can space it out by making a marinade or braising their meat a day or two in advance.

“Our signature dish of posole [Clam Pozole Verde: beans + cilantro + clams + clam liquid + garlic + hominy + jalapeño + olive oil + poblano peppers + radishes + tortillas + vinegar] came about as a conceptual dish that I didn’t know how I was going to execute before we opened. Then one day, one of our sous chefs made a green sauce for family meal. I threw it into the cooking liquid for the clams, and there you go.

Early on in my career, some days I was more creative than others, and I just sort of accepted that fact—the same way that I accepted the fact that some people were more creative than others. But I started to really challenge that.… Now, I believe that creativity can be systemized.

—DANIEL HUMM, Eleven Madison Park (New York City)

“When I started here, I didn’t want to serve dishes I had served in the past,” he says. I felt some had gotten too contrived. I wanted the food to be good products cooked simply, put on the plate with care but without being so focused on what they looked like.

“I think Instagram was an important part of [developing] my food. I can see looking at the pictures since we opened that it helped me define what my style is. What my food is now is probably the first time I’ve ever been happy with it acknowledges Fox.”

James Kent recalls his days as chef de cuisine at Eleven Madison Park and the rigorous development process every dish on the menu went through. “We never put it on the menu unless we loved it,” he recalls. “Daniel Humm was definitely the creative driving force at EMP at the beginning, but we learned that the results were even better if we all contributed. So we’d have weekly meetings to discuss the food—Daniel, Bryce Shuman [now of New York City’s Betony], Angela Pinkerton [then the pastry chef], and I would meet to talk about ideas. We’d throw ideas out during brainstorming, or pick a theme—like scallops + tomatoes—and work around that. We do the same thing here [at the NoMad]. I’ve worked at restaurants where as a young cook I couldn’t be creative, and those were places where I learned to cook, picking up techniques and recipes and how to weigh ingredients and a strong work ethic—but I left with limitations. I want to teach my cooks not to be my drones, but how to think about food for themselves. Cooks are problem solvers—we must know how to adapt. Every time, the lamb is different. Every time, the leeks are different. You’ve got to learn to think on the fly and evolve.”

I’ll mentor my cooks who want to create new dishes. They’ll present me with dishes they’re working on, asking me, “What do you think?” I’ll taste them, and ask, “What is missing?” That alone pushes them in their thinking. If they can figure it out themselves, great—and if not, we have a conversation until we get there.

—GABRIEL KREUTHER, Gabriel Kreuther (New York Ci ty)

CHANGE THE WORLD THROUGH THE POWER OF FOOD.

—THINKFOODGROUP’S corporate mission statement

A CASE STUDY IN CREATIVE COLLABORATION: JOSÉ ANDRÉS’S THINKFOODGROUP

We spent a few hours at Chef José Andrés’s ThinkFoodGroup in Washington, D.C., with his team—including executive chef Joe Raffa, pastry chef Rick Billings, and head of R&D Ruben Garcia—who are charged with infusing creativity into the company and making it systematic. The tour of the office spotlighted vision boards dedicated to new restaurant concepts and other projects, complete with white board notations and lots of photos, as well as a test kitchen and a room lined with couches for brainstorming sessions.

Rick Billings, pastry chef: Ideas are cheap. Our motto here is: “It’s not about ideas—it’s about making ideas happen.”

It’s true that creativity can’t be forced. Sometimes it just happens. However, we wanted to create an incubator so creativity happens more often.

Chefs are good at creating, but we’re not always the most linear people, so it’s especially important to find a way to stay focused and organized. We’re forever changing our formats and templates. Each restaurant we’re working on has two boards: 1) a pre-concept board which is the genesis of the starting point, along with a digital folder on the computer; and 2) a conceptual board. We have a lot of different restaurants, but we never take a cookie cutter approach to them. José loves when food tells a story.

Our sources of inspiration definitely include books, because we must always know the reference point for a dish. Tasting good and being pretty isn’t enough of a reason for the existence of a dish here, even if it is at other places. Dishes are too often missing that third element, whether it’s being whimsical, historical, or having some other context.…We’ll never serve dishes simply for the sake of technique. If there’s a guava sphere on a dish, why? But if there’s an olive sphere in a dirty martini, it isn’t forced—you get it.

José is huge on photos, including on Instagram and Twitter. We need to learn to think like him.

José isn’t in the kitchen cooking, but he’s always watching everything. So you never want him to be the first to see mistakes. It’s the sous chefs’ jobs to find the mistakes before the chefs do.

Ruben Garcia, director of R&D: I read between the lines, so I know what José wants before he says it out loud. A dish has to have three things: good product, good technique, and context. And a team has to be better than me, which makes my life easier—to make the team proactive, I need a system.

Joe Raffa, executive chef: We learned through one trip to Spain that it’s severely ineffective to “wing it.” So all our research trips are planned out extensively. We went to China with 11 people six years ago when we were researching the concept for China Chicano, and hit three or four restaurants a day where we’d order the entire menu. We learned to organize trips by day and location, and by restaurants and dishes. We’ll name all the photos at the end of the day, and collect menus from the restaurants, making as many contacts as possible with chefs, farmers, winemakers, and mixologists, and organize all their contact information. We’ll also pull together all the photos and a master list of all the business cards and menus, so nothing is lost.

Rick Billings (left) and Joe Raffa (right)

When we finally start cooking, we’re always sharing information. This is a collaborative, not a competitive, process. When testing recipes, we document each dish with photos, timing, temperature, and weight. Through repeated testing, we see the menu start to come to life. Then we’ll ask ourselves, “What’s missing?” This process gives form to the menu, and when we finally have José taste the dishes we’ve developed, it gives additional direction to our efforts. Without this system, each of us is too much in our individual heads—but with it, it allows us to go from concept origination to operation as a team. And we treat the process just like we treat the food here: It’s a continual evolution.

We strive to be creative, but it’s still a business and we still need to make money. We do that by raising the experience level. Where do we spend our money? We invest in high-impact details. Do we have to get our chocolate, grasshoppers, and Mezcal from Mexico [for Oyamel]? No—but we do. And we pay to have experts like Diana Kennedy and Carmen “Tita” Ramirez [Degollado] come into the kitchen for ten days at a time to cook with our team at Oyamel, and Aglaia Kremezi to do the same with our team at Zaytinya. We need to hone our palates to make sure we’re doing the right thing, since what we do isn’t always traditional from a cultural standpoint. The flavor has to be right. And the return comes later down the line.

It’s never just about recipes—it’s about how you present them, and how you serve them.

José changed the hierarchy in the company. He laid the [organizational chart] on the floor so that it’s flat—meaning that everyone here talks to everyone else. This way, egos don’t dominate. Blatant egos can’t make it here. You have to be able to contribute, and you have to not always have to win. We allow everyone—from José to an intern—to give feedback.

Kent applies the creative approach he learned at EMP to his kitchen at the NoMad. “At EMP we’d have ‘Food Battles,’ where everyone in the kitchen would have to make a canapé, and we’d taste each other’s dishes. Or we’d do Battle Broccoli, and the next Wednesday everyone would make a broccoli dish. Even the pastry team was charged with coming up with savory ideas. We had a Flatbread Battle here [at the NoMad], and the winner was a flatbread with mozzarella and tomatoes and peaches. We’ll work on R&D every Friday, and will document and photograph dishes and email them to the whole team. While the [executive team] focuses on the summer menu, the line cooks will focus on fall food—they’ll draw dishes and write out the recipes for 50 or 60 dishes that would make sense on our menu (e.g., no sushi). We’ll pick five or six concepts for the cooks to make, present, and have tasted, and occasionally we’ll end up tweaking one or two that will make it onto the menu, often in a very different form. The goal is to have everyone contribute—the process is as much about team-building as it is about creativity. We want them to be proud of where they work, and to talk about the restaurant as ‘we,’ instead of ‘they,’ which shows they’re really invested in the restaurant.”

I’m inspired by Eddy [Leroux, of Daniel], who’s always bringing in new ingredients and researching their origins and usage and applying his French technique to them. He’s always pushing himself outside his comfort zone and educating himself, yet everything he makes is perfect and refined. That’s an inspiration.

—AARON BLUDORN, Café Boulud (New York City)

Daniel Humm has observed that at Eleven Madison Park, “It is unbelievable what we have learned from cooks who have only worked with us for six months or a year. Then we do the same on a higher level, where the sous chefs [go through this process as well]. In the end, it doesn’t matter if the dish ends up on the menu [because] it’s amazing what a collaborative environment creates.…[During this process the dining room is also involved] because even if you are not a chef you can have a great idea about food or how it is served.”

In the end, the most important lesson Humm has learned from the process is reflected at left.

I found that there was a [70 percent] correlation between perceived SOCIAL SUPPORT and HAPPINESS. This is higher than the connection between smoking and cancer.

—SHAWN ACHOR,

author of The Happiness Advantage

EVERYONE IS CREATIVE. I’ve seen people who thought they weren’t creative become some of the most creative. There is no excuse. If you create an environment where everyone thinks creatively and collaboratively, it’s like a muscle that you train.

—DANIEL HUMM, Eleven Madison Park (New York City)

Daniel Boulud with Eddy Leroux, Travis Swikard, Ghaya Oliveira, Jean-Francois Bruel, and Aaron Bludorn

While Daniel Boulud is often singled out for his culinary prowess, he insists, “There’s no great chef without a great team.”

Boulud has selected and trained a great team indeed, one whose members inspire others’ creativity as much as they are inspired by Boulud himself.

[Pastry chef] Ghaya Oliveira’s Grapefruit Givré [a dessert made from a frozen hollowed grapefruit filled with grapefruit sorbet, grapefruit jam, sesame crumble, sesame foam, and rosewater loukoum, topped with halva “hair”] is the latest classic [dessert]. The year before we opened, I took a trip to Turkey and I was eating all this crazy stuff—loukoum [aka Turkish delight, candies made from a gel of starch + sugar], rosewater, halvah [a fudge-like confection made from sesame paste]—a lot of things with sesame. Ghaya is Tunisian, so this was a little voyage toward the eastern Mediterranean where she grew up. The beginning of the idea was the loukoum and the sesame. Then we added the citrus, and that’s how the dish developed a little bit more and eventually became the Givré.

—DANIEL BOULUD, The Dinex Group, which includes Manhattan’s Daniel, Café Boulud, Boulud Sud, Bar Boulud, db bistro moderne, DBGB Restaurant and Bar, and other restaurants globally

A CASE STUDY IN CREATIVE COLLABORATION: NATALIE’S AT THE CAMDEN HARBOUR INN IN MAINE

Camden, Maine, is one of the last places on earth we ever expected to discover a restaurant that is a beacon of culinary excellence in America. Yet on each of multiple visits to Natalie’s at the Relais & Châteaux–affiliated Camden Harbour Inn, we found wildly impressive cooking by 30-something married co-chefs Shelby Stevens and Chris Long, graciously and flawlessly served by an expertly trained staff.

The credit for Shelby and Chris’s captivating cuisine resides no doubt in the training they absorbed both separately and together via working under some of America’s best chefs, including Daniel Boulud (at New York’s Daniel), Daniel Patterson (at San Francisco’s Coi), Ana Sortun (at Cambridge’s Oleana), and the late Charlie Trotter (at Chicago’s Charlie Trotter’s).

But the excellence of the entire dining experience also seems to be the result of the chefs’ creative process paired with an exceptionally thorough process of vetting each new dish, then sharing it with and seeking feedback from the front-of-the-house staff through not one but two team tastings during each change of the menu, which happens every six to eight weeks.

Chefs Shelby Stevens and Chris Long on the Team Approach

“For our first eight menus, we pulled out Culinary Artistry to see what was in season each time. Now, we have our own notebook tracking what is in season here [in northern Maine] and we pull that out. We go through it to see what sounds fun and what we want to work with that’s in season first.

“We also look to see what will challenge us, from terrines to tableside smoke. [Chris] saw the smoke dish when [he] spent a week at Alinea staging before moving here from Chicago. At Alinea, the quality of ingredients is spectacular but the amount of people was double that working at Trotter’s. You had people who were only focusing on half a dish.

“We will talk about the ingredients at home. We like working on this at home because, well, we are sitting and eating and no one is interrupting us, versus at work. At home, the only one who needs anything is our dog—and he can wait.

“We will look at the whole menu and all of a sudden realize, ‘Oh, crap—there is no sauce on this dish.’ So what is the sauce or the puree? What is the crunch, the acid? We then run through the tastes and the textures together.

“We love changing up an ingredient on the same plate, so you might see charred leeks, leek ash, and fried leeks together. We will do potato puree with a potato chip, or carrot puree with a carrot pickle. Celery root puree, celery root leaves, celery root chips and ribbons, and now you have four elements of celery root. The flavors complement each other and it is good for food cost—no waste.

“We have worked with cooks who would say, ‘We need something red in this dish.’ But ‘red’ is not a flavor. You can say a dish needs more color, and work to find that flavor and a bright note.”

Chris Long (left) with Bart van der Velden

We don’t end our creative process until we know the dish can be set down in front of a guest exactly the way we want it to be.

—SHELBY STEVENS AND CHRIS LONG, co-chefs, Natalie’s at Camden Harbour Inn

• First-Draft Menu

“We write the menu and email it to everyone, then two weeks later we do the formal tasting for them. It turns out to be about 20 or more dishes. We get input from everyone and make the adjustments.

“We have never had a dish not work on the menu because it gets tasted so many times. You have Raymond [Brunyanszki, the co-owner], who has eaten everywhere; Bart [van der Velden, the GM], who has a great palate; and Micah [Wells, the sommelier], who knows his wines. We go through them—the heavy hitters—first, and then two days later, we do a second-round tasting for the entire crew.”

• Tableside Service

“When [Shelby] worked at Daniel, [she doesn’t] think a single sauce ever went on a plate. They did not sauce in the kitchen. If a guest steps in the way or a server misses a step, there goes the dish.

“With a soup being served tableside, you can see all the different garnishes before the soup gets poured in. You would not see all that work if we portioned it in the kitchen. With a soup, we also control how much gets poured—not too much or too little.

“It is fun for the guest because it engages them and wakes them back up. If they are sitting for seven courses you want to bring them back in again.

“With tableside saucing, we will show the server exactly where to pour the sauce and how much, because one tablespoon too much might make the dish too salty. The presentation is very exact. It also engages the staff to be more present. It brings them all closer.”

• First Tasting

The inn’s well-traveled co-owner Raymond Brunyanszki sits down with a few key members of the staff—including general manager Bart van der Velden, restaurant manager Timothy O’Neill, wine director Micah Wells, and mixologist Trevin Hutchins (of both Natalie’s and sister property the Danforth Inn in Portland)—and together they taste and discuss every one of Shelby and Chris’s proposed new dishes and pastry chef Brian Song’s desserts. It’s a thoughtful session focusing on how to elevate its flavor even further or enhance its tableside presentation or wine-friendliness, and at the end of it, Shelby and Chris are provided with detailed feedback on each dish. Following are bits and pieces of their conversation:

Bart: There’s never too much cheese in a dish for me—but that was a lot of blue cheese.

Raymond: I’m not sure about the portion size. Is it an appetizer, or an entrée? If it’s an appetizer, maybe it needs to be slightly smaller with more acidity.

Trevin: To my palate, a lot of the elements on this plate read sweet.

Micah: I’ve got a big, fruit-forward, old-viney wine to pair with this.

• Second Tasting

A couple of days later, there is a second tasting of revamped dishes for members of the kitchen and front-of-the-house staffs, led by general manager Bart van der Velden.

Everyone is provided with detailed descriptions of each dish on a “cheat sheet” that they are expected to memorize, and on which they’re later quizzed (“Which dishes are gluten-free?” “All our dishes can be made dairy-free except which dishes?” “What silverware should be served with this dish?”). Everyone pulls out an iPhone to photograph each dish and takes notes on how each is to be served. After it’s shot, they pull out forks to take a bite of each dish, and have a firsthand experience of it. Micah describes his recommended wine pairing for each dish, and the rationale behind each pairing, giving the key characteristics of the dish enhanced by certain characteristics in the wine. He underscores that a regular pour is 6 ounces, while a pairing pour is just 3 ounces.

Wait staff are cold-called to describe each dish, based on the ingredients and techniques mentioned on the cheat sheet. Bart coaches them, “Use terms like ‘on top of’ and ‘on the side with.’” As certain ingredients are mentioned, more pop quizzes take place: “What’s a Meyer lemon?” “What’s a persimmon?” When the Maine lobster dish is brought out, it’s emphasized that this is one of the signature local dishes on the menu. Micah describes a Pommery Brut Royal Champagne that has been branded for the Relais & Châteaux organization, which consists of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier grapes in nearly equal amounts. The restaurant’s lobster tasting menu is described, along with the selling points of the restaurant’s most expensive menu: It features four luxury ingredients—truffles, caviar, foie gras, and local Maine lobster—and the staff is reminded that Chef Chris Long was named Maine’s 2013 Lobster Chef of the Year. The lobster roll has been re-plated on a platter, replacing the previous paper dish version which was deemed “too cute” for the winter months.

Chefs Shelby Stevens and Chris Long Reflect on the Process

“Raymond has an amazing palate. He eats out everywhere, so his palate is also always on trend. There are certain ingredients he just doesn’t like—like bell peppers, and pineapple—so we don’t use them.

“While it hurts at first to be critiqued, sometimes important improvements result.…The pasta dish really improved between the first and second tastings. We made sure to use smaller pieces of blue cheese, and to use more chestnut, which we also roasted a bit longer in brown butter.

“Our inspiration for our oyster velouté dish came from our dinner at Eleven Madison Park with Raymond. They did it very differently there, but we talked about how we could do something similar.”

Raymond Brunyanszki Reflects from an Owner’s Perspective

“Chris and Shelby are very open-minded, and want the best for our guests. I came up with the idea of having staff tastings of the new menu and having the cooks involved in the tasting of the menus, so they get some sense of participation in the creation of the menu. And I sat down with the kitchen team to understand the thought process behind the new menu.

“It’s not just tasting a dish—it’s thinking through the presentation, and the way a guest puts their fork into it and takes a bite and the layers of flavor they get on each forkful. Do you get a balanced flavor profile on each bite?

Shelby Stevens (right), with Raymond Brunyanszki and Trevin Hutchins

“So it’s not just, How does it taste? It’s also, Is it seasonal? Is it from our gardens, or sourced locally? How does it look? For me, it’s also very important to have ‘safe spots’ on the menu for guests—e.g., halibut, beef, a vegetarian option—who are not used to fine dining so they still see some dishes they recognize and feel comfortable coming into the restaurant.

“While the final menu runs for six to eight weeks, we pay especially close attention to feedback from our regulars, so we can take their opinions into account, too.”

Dan Barber of Blue Hill on Creativity

Dan Barber credits much of his creativity as stemming from his ten years of research for his book, The Third Plate, which argues that the move from commercially produced food (Plate #1) to farm-to-table cuisine (Plate #2) isn’t sufficient, but that culinary evolution must also reflect a shift toward a more plant-driven cuisine that supports the underlying farm economy (Plate #3).

The Third Plate

When I started my book project, I thought it was simply about farm to table, and celebrating connections with a very inspiring group of farmers, artisans, scientists, and breeders.

But then I went to write about wheat and my wheat guy, Klaas Martens. I found myself standing in the middle of a 2,000-acre field and there was no wheat, but there were soil-building crops and all these things that were going to build the soil so the wheat would be delicious. But I saw the wheat was a very small percentage of the success of the farm ecologically—and was relying on a bunch of other crops, like buckwheat and Austrian winter peas, that no one was buying or talking about at the time. I had the insight that if I was going to celebrate the wheat, I had to celebrate everything that goes into the wheat.

That’s when I realized that farm to table doesn’t work—and that I was a farm-to-table chef without any clothes. I was advocating for something that didn’t change the landscape, and didn’t promote a different type of food system that would become a more sustainable way to eat in the future.

That was a seminal moment when I realized I had it all wrong—and my farm-to-table book evolved into The Third Plate.

No Printed Menus

At Blue Hill at Stone Barns, I have to figure out a cuisine that supports the whole system, the “nose-to-tail” of the farm. That forces creativity because you are restrained in your pantry. Restraints always kickstart creativity. The more restrained, the easier it is. The most frustrating time is July through October, because there are so many ingredients available, and they are all just singing.

I think true gastronomy comes through the transmutation of food into something else. To cook a steak is to heat a piece of protein, but to make oxtail taste good is transformative. That’s where cooking and creativity really is. The gastronomic side is so important for the agricultural side. You have to eat the whole animal—that’s an easy one. But you also have to eat the whole vegetable—stalk and leaves, too. What supports the [economic] system supports the rest of the flora and fauna.

You need to dial back to the seed—that is the blueprint. Once you have selected the seed, the cake is baked. The captain will interview the table after the guests sit down, and will profile the table for the kitchen [where the menu and number of courses then gets determined for each individual table]. Fewer than 10 percent of guests might be “people who could care less about the farm and are drinking big Chardonnay!” We love those people because they will get the steak from the cow that we don’t want to serve someone else who has waited months to eat here and doesn’t just want a steak they could get someplace else.

Dan Barber

But more than 90 percent of our guests are open to experiencing what we do and more unusual courses. We have worked very hard for that. When we opened, 90 percent of our guests wanted steak, and we needed to survive in order to stay open.

wastED

WastED [Blue Hill’s month-long pop-up serving 100 percent recycled ingredients] came about in part from the wheat experience. There was not a market for all that was grown—so it either got plowed back into the ground or fed to pigs. Forty percent of what is produced ends up in the trash, either before or post-consumer, which is a pretty staggering number.

So it got us thinking: What if we ate those grains directly? What if we thought about a meal not just as a delicious celebratory experience but as an educational one as well—one that connects you to a more meta-level thinking about the table as a place of connection to a lot of different things? And what if we used that time to connect guests to larger issues—issues that affect the world, and connect guests with something bigger?

Nothing is bigger than food, which is something we all know.

Evolving Creativity

Some creativity is a kind of reading the winds of culture. I don’t do any of that. I get my ideas from the ecological agriculture space, 100 percent. A lot of inspiration is how you connect the pieces.

There are ways to be supercreative in a quiet, almost imperceptible way that is conscious and incremental over ten years.…I can now be fearless and bold because I have the tools to do it.

wastED veggie burger (made from juice pulp) featured at Shake Shack

THE KITCHEN CREATIVITY 50

A list to spur ideas when you need it.

1. Be inspired. Choose a song, a book, a movie, a painting, or another creative work in another medium, and capture it in a dish. 2. Celebrate the past. Classic dishes are classic for a reason—celebrate that reason. 3. Connect the seemingly unconnected. If you look, you’ll inevitably find one—because everything is connected. Claudia Fleming combined sautéed plums and tomatoes in a dessert showcasing the fruits’ tart sweetness. 4. Constrain it. Embrace your constraints (e.g., lack of equipment, ingredients, time), and find a way to work around them. 5. Cross-breed. Combine two different ideas into a single concept, e.g., a croissant with a donut (the cronut). 6. Deconstruct. Break a well-known dish into its component parts, and serve them separately. 7. Describe it whimsically. Instead of an oyster topped with granite, call it an “oyster Slurpee.” At the Inn at Little Washington, dishes are also sometimes “nestled” or served in a figurative “wreath.” 8. Don’t fake it. Don’t pretend to be something else (i.e., “mock”)—celebrate another alternative that works instead of the usual, e.g., tomato gazpacho  carrot gazpacho, or Buffalo chicken wings

carrot gazpacho, or Buffalo chicken wings  Buffalo fried cauliflower with blue cheese and celery. 9. Embrace the opposite. As the popular Black and White Cookie proved, opposites can indeed attract, e.g., high/low (e.g., caviar beggars’ purses), vegan/carnivore (e.g., carrot tartare, cauliflower steak), and other dichotomies. 10. Feed your ingredient something different. You are what you eat—and what what you eat eats. At Blue Hill, Dan Barber fed us two eggs from two different chickens in the same dish—and the one fed only red peppers had a yolk that was distinctly reddish, making an unforgettable impression. 11. Ingredient-shift. Instead of apples, substitute pears. Instead of peanuts, try pecans. 12. Interactivate it. Serve it with a knife for guests to cut themselves, e.g., sprouts off a kalette branch, à la Dan Barber at Blue Hill. 13. Localize. Make it from ingredients procured within a 100-mile or ten-acre radius (or closer!). 14. Make a look-alike. Make it appear to be something familiar (e.g., a fried egg) with unfamiliar ingredients (e.g., cattails and tree bark), à la Damon Baehrel. 15. Mimic nature. Be inspired by the outdoors (e.g., dew, smoke, snow) and bring these elements magically indoors. 16. Miniaturize it. Make it much smaller than usual (e.g., hamburger

Buffalo fried cauliflower with blue cheese and celery. 9. Embrace the opposite. As the popular Black and White Cookie proved, opposites can indeed attract, e.g., high/low (e.g., caviar beggars’ purses), vegan/carnivore (e.g., carrot tartare, cauliflower steak), and other dichotomies. 10. Feed your ingredient something different. You are what you eat—and what what you eat eats. At Blue Hill, Dan Barber fed us two eggs from two different chickens in the same dish—and the one fed only red peppers had a yolk that was distinctly reddish, making an unforgettable impression. 11. Ingredient-shift. Instead of apples, substitute pears. Instead of peanuts, try pecans. 12. Interactivate it. Serve it with a knife for guests to cut themselves, e.g., sprouts off a kalette branch, à la Dan Barber at Blue Hill. 13. Localize. Make it from ingredients procured within a 100-mile or ten-acre radius (or closer!). 14. Make a look-alike. Make it appear to be something familiar (e.g., a fried egg) with unfamiliar ingredients (e.g., cattails and tree bark), à la Damon Baehrel. 15. Mimic nature. Be inspired by the outdoors (e.g., dew, smoke, snow) and bring these elements magically indoors. 16. Miniaturize it. Make it much smaller than usual (e.g., hamburger  slider, cake

slider, cake  cupcake). 17. Minimalize it. Eliminate one more ingredient up to the point that risks losing the essence of the dish. 18. Mock it. Make your apple pie with Ritz crackers instead of apples. Make your gyro with seasoned seitan instead of lamb or beef. 19. Pair with a beverage. Create a presentation of those oysters with an accompaniment of Chablis, Sancerre, or a stout. 20. Pair with its soulmate. The Inn at Little Washington has served an amuse-bouche of a grilled cheese sandwich the size of a silver dollar, accompanied by a shot of tomato soup. 21. Pay homage. Create a tribute to a famed, or favorite, version of a dish—whether Escoffier’s or your grandmother’s. 22. Perspective-shift. Imagine the dish from another point of view, e.g., that of a child, a Martian, or the main ingredient itself. 23. Plate it. Beautify the elements via inventive plating, e.g., truffled popcorn served in a red-and-white-striped movie popcorn box. 24. Platform-shift. Serve expected flavors in an unexpected way, e.g., Caesar salad ice cream or soup. 25. Play with words. Pair lamb with lamb’s lettuce, as we first saw Lydia Shire do at Biba. 26. Portable-ize it. Make a handheld version—e.g., as a push-up, on a stick, in a wrap. 27. Present whimsically. When the Inn at Little Washington serves a single gougère on a pedestal, it elevates the single bite both literally and figuratively. 28. Reconstruct it. Take the component parts of a well-known dish and reassemble them in a new way (e.g., clam chowder as potato and chive gnocchi with clam sauce). 29. Reinterpret it. Use a classic dish as your inspiration, and give it your own spin. 30. Reverse it. Lydia Shire’s version of vitello tonnato (veal with tuna sauce) flipped the dish into tuna with veal sauce. 31. Revisit a childhood memory. This allows the brain connections between your memory cells and stored “lessons learned” to gain strength and speed. 32. Satirize it. Serve a meal in a TV dinner tray circa 1970s. 33. Sauce it. Add an irresistible sauce. José Andrés served us a dish with a romesco so delicious that anything that accompanied it would have been a knockout. 34. Senza it. Create a something-free version, e.g., senza gluten (GF chickpea pasta). 35. Serve it tableside. A flair for the dramatic can enhance the experience of your dish, such as tableside carving (e.g., of a roast, whether meat or vegetable) or flambéing. 36. Shape-shift. Change the usual shape—e.g., serve a round sandwich, instead of a square. 37. Solve a unique problem. Think big: “How to reduce America’s 40 percent rate of food waste?” Dan Barber’s veggie burgers made from leftover juice pulp was one of the best we’ve ever tasted. 38. Stuff it. Slip a soft-cooked egg inside the muffin you’re baking, à la Craftsmen & Wolves’ The Rebel Within, or the “gnocchi” you’re making, à la Michael Voltaggio’s at ink. 39. Super-size it. Make it much larger than usual—e.g., the TKOs (Thomas Keller Oreos) at Bouchon Bakery, which are elegant, gigantic chocolate shortbread cookies sandwiched around a creamy white chocolate filling. 40. Sustainable-ize it. Substitute biodynamic and/or organic ingredients from your local farmer. 41. Taste-shift. Serve a savory version of a typically sweet dish (e.g., babka)—or vice versa. 42. Technique-shift. Prepare a dish that’s typically cooked one way in another way. Instead of grilling it, try wok-frying it. 43. Temperature-shift. Serve a cold version of something that’s typically served hot, e.g., frozen hot chocolate. 44. Theme it. Patrick O’Connell serves a dessert plate inspired by the seven deadly sins. 45. Time-shift. Imagine what a version of this dish will look like 50 years into the future. 46. Treat vegetables like meat. Confit vegetables, grill them, grind them (e.g., in a meat grinder attached to the table, à la Eleven Madison Park), roast them, serve them as steaks. 47. Vary it. Serve the same ingredient multiple ways on the same plate—e.g., ashed, cold, cooked, crunchy, dehydrated, fermented, foamed, frozen (e.g., sorbet), hot, juiced, moussed, raw, reconstituted, savory, soft, sweet, tartared, tempura-fried. 48. Veg-ify it. Create a meatless option with the same flavor and allure, e.g., Tal Ronnen and Scot Jones’s “lox” made from sous-vide smoked carrots. 49. Waffle it. Just kidding. Or not—Daniel Shumski turned this idea into his bestselling first book, Will It Waffle?, detailing everything you can waffle besides waffle batter, from mac-n-cheese to oatmeal chocolate chip cookies. Find a new, unexpected use for a piece of equipment, a technique, or an ingredient. 50. Waste not. Use carrot tops in your pesto, and create banana cupcakes with those black bananas.

cupcake). 17. Minimalize it. Eliminate one more ingredient up to the point that risks losing the essence of the dish. 18. Mock it. Make your apple pie with Ritz crackers instead of apples. Make your gyro with seasoned seitan instead of lamb or beef. 19. Pair with a beverage. Create a presentation of those oysters with an accompaniment of Chablis, Sancerre, or a stout. 20. Pair with its soulmate. The Inn at Little Washington has served an amuse-bouche of a grilled cheese sandwich the size of a silver dollar, accompanied by a shot of tomato soup. 21. Pay homage. Create a tribute to a famed, or favorite, version of a dish—whether Escoffier’s or your grandmother’s. 22. Perspective-shift. Imagine the dish from another point of view, e.g., that of a child, a Martian, or the main ingredient itself. 23. Plate it. Beautify the elements via inventive plating, e.g., truffled popcorn served in a red-and-white-striped movie popcorn box. 24. Platform-shift. Serve expected flavors in an unexpected way, e.g., Caesar salad ice cream or soup. 25. Play with words. Pair lamb with lamb’s lettuce, as we first saw Lydia Shire do at Biba. 26. Portable-ize it. Make a handheld version—e.g., as a push-up, on a stick, in a wrap. 27. Present whimsically. When the Inn at Little Washington serves a single gougère on a pedestal, it elevates the single bite both literally and figuratively. 28. Reconstruct it. Take the component parts of a well-known dish and reassemble them in a new way (e.g., clam chowder as potato and chive gnocchi with clam sauce). 29. Reinterpret it. Use a classic dish as your inspiration, and give it your own spin. 30. Reverse it. Lydia Shire’s version of vitello tonnato (veal with tuna sauce) flipped the dish into tuna with veal sauce. 31. Revisit a childhood memory. This allows the brain connections between your memory cells and stored “lessons learned” to gain strength and speed. 32. Satirize it. Serve a meal in a TV dinner tray circa 1970s. 33. Sauce it. Add an irresistible sauce. José Andrés served us a dish with a romesco so delicious that anything that accompanied it would have been a knockout. 34. Senza it. Create a something-free version, e.g., senza gluten (GF chickpea pasta). 35. Serve it tableside. A flair for the dramatic can enhance the experience of your dish, such as tableside carving (e.g., of a roast, whether meat or vegetable) or flambéing. 36. Shape-shift. Change the usual shape—e.g., serve a round sandwich, instead of a square. 37. Solve a unique problem. Think big: “How to reduce America’s 40 percent rate of food waste?” Dan Barber’s veggie burgers made from leftover juice pulp was one of the best we’ve ever tasted. 38. Stuff it. Slip a soft-cooked egg inside the muffin you’re baking, à la Craftsmen & Wolves’ The Rebel Within, or the “gnocchi” you’re making, à la Michael Voltaggio’s at ink. 39. Super-size it. Make it much larger than usual—e.g., the TKOs (Thomas Keller Oreos) at Bouchon Bakery, which are elegant, gigantic chocolate shortbread cookies sandwiched around a creamy white chocolate filling. 40. Sustainable-ize it. Substitute biodynamic and/or organic ingredients from your local farmer. 41. Taste-shift. Serve a savory version of a typically sweet dish (e.g., babka)—or vice versa. 42. Technique-shift. Prepare a dish that’s typically cooked one way in another way. Instead of grilling it, try wok-frying it. 43. Temperature-shift. Serve a cold version of something that’s typically served hot, e.g., frozen hot chocolate. 44. Theme it. Patrick O’Connell serves a dessert plate inspired by the seven deadly sins. 45. Time-shift. Imagine what a version of this dish will look like 50 years into the future. 46. Treat vegetables like meat. Confit vegetables, grill them, grind them (e.g., in a meat grinder attached to the table, à la Eleven Madison Park), roast them, serve them as steaks. 47. Vary it. Serve the same ingredient multiple ways on the same plate—e.g., ashed, cold, cooked, crunchy, dehydrated, fermented, foamed, frozen (e.g., sorbet), hot, juiced, moussed, raw, reconstituted, savory, soft, sweet, tartared, tempura-fried. 48. Veg-ify it. Create a meatless option with the same flavor and allure, e.g., Tal Ronnen and Scot Jones’s “lox” made from sous-vide smoked carrots. 49. Waffle it. Just kidding. Or not—Daniel Shumski turned this idea into his bestselling first book, Will It Waffle?, detailing everything you can waffle besides waffle batter, from mac-n-cheese to oatmeal chocolate chip cookies. Find a new, unexpected use for a piece of equipment, a technique, or an ingredient. 50. Waste not. Use carrot tops in your pesto, and create banana cupcakes with those black bananas.

Otherwise, to be creative in the kitchen, try finding a way to apply any concept from another field to food and drink. For example,

• In music, variation is a formal technique through which material is repeated, albeit in a different form (e.g., through counterpoint, harmony, melody, orchestration, rhythm, timbre, or some combination thereof). Imagine: How could you create a variation on the dish or drink you’re working on? How could you provide it with a counterpoint? What new ingredient would harmonize beautifully with all its existing ingredients?

• In literary criticism, deconstruction (whose Greek root itself means to break up, or to loosen) is a form of analysis of the relationship between text and meaning. Imagine: What are each of the elements that make a dish that dish? Think about each individually. How could you (re)present each separately? How could they be recombined in a new way?

• Apply analogies from other fields and disciplines in the arts (beauty), sciences (truth), and ethics (goodness).