CHAPTER 5

TARO

Spring 1933

“Taro, do you hear that?”

Little Taro tilted his head and listened. A sound like two boards slapping together, like geta clogs stamping on wood. The click-clack call of the kamishibai man! Taro’s father hustled him into his shoes and a warm cotton jacket, and they were off—running up the street, turning the corner, hoping to beat the crowd. But it was too late, as always. Every child in the neighborhood was already there—and more than a few adults, too. They crowded around old Uncle Kamishibai—this uncle was a new one to Taro, with long hanging earlobes and a shiny golden tooth. He smiled and waved the children closer to his bicycle booth. The wooden kamishibai box on the back was open at the bottom—a drawer full of sweets! Taro’s father elbowed the way forward and hoisted Taro into his arms to look inside the drawer. Taro chose two barley rice treats. His father clucked his tongue and handed over a coin.

“Thank you, Oji-san,” Father said respectfully.

“Arigatō gozaimasu, Oji-san,” Taro said.

His father held out his hand. “Give me one for later, Taro. Mother will say we’ve spoiled your dinner.”

Taro handed the rice-paper-wrapped treat to his father, sadly watching it disappear into the gray suit pocket. Another hoist, and Taro was on his father’s shoulders. They joined the back of the crowd as the old man set up his theater. The drawer slipped back inside the bottom of the box, and the top lifted up until the dark wood became a picture frame. The sides slid open like curtains in a movie theater, and suddenly it grew as quiet as the cinema when the lights go down.

Uncle lifted a thick yellowed paper card from the back of the box and slid it into place. The wooden frame was suddenly a window onto a forest. And Uncle said in a kindly voice that carried across the crowd, “There once was a very old couple who were not blessed with children of their own. Every day, the old man would go into the forest to gather twigs and sticks to sell as firewood, and the old woman would go down to the river to wash clothes . . .”

Taro made a low sound in his throat and clutched his father’s shoulder. He knew this story! It was “Momotaro, the Peach Boy.” He was a Taro, too—and a hero!

The kamishibai man shifted his voice to that of a little old woman. “Grandfather, Grandfather, look what I have found floating in the river!” The window frame showed the little couple inside their house, marveling at a giant momo, a peach.

“Let us cut it up and eat it together,” said Uncle in the voice of an old man. But before they could cut the peach, it split open, revealing a beautiful little boy with shiny black hair and bright brown eyes.

“Your prayers have been answered. I have been sent from Heaven to be your loving son!” Uncle said in a strong young voice.

All of the children cheered, Taro included. His father patted his leg, bouncing him a little.

In the next illustration, the couple rejoiced and named their new son after the peach in which they had found him. Momotaro grew big and strong on Grandmother’s millet dumplings.

“But then one day they heard of terrible doings. An island of demons was threatening the villages on the shore!” Uncle continued.

The children hissed and booed. The slides grew darker. Taro hid his face behind his fingers. Blood-red oni—demons with gnashing yellow teeth and rolling white eyes—filled the window, laughing and screaming as they stole food and money from the poor innocent villagers.

Then came the part Taro loved. Momotaro announced he would go to punish the demons. His mother made him a sack of dumplings, and his father wished him luck. He struck out across the countryside. Along the way, he met a dog.

“Momotaro, where are you going?” the kamishibai man howled.

And all the kids shouted, “I am going to fight the demons!”

“I am hungry,” Uncle howled. “Give me a dumpling, and I will go with you!”

In the picture window, Momotaro tossed a delicious millet dumpling into the dog’s open, smiling mouth. Then the two friends set off together, until they met a monkey. The monkey and dog fought terribly until Momotaro called out for them to stop.

“Momotaro, where are you going?” the kamishibai man yowled in his funny monkey voice.

And all the children cried, “We are going to fight the demons!”

“I am hungry. Give me a dumpling, and I will join you!” Uncle revealed a slide of the monkey hanging from a tree above Momotaro, reaching for the offered treat. Then the three friends traveled down the road until they met a pheasant.

“Momotaro, where are you going?” the kamishibai man asked, this time in a whistling cheeping voice.

“We are going to fight the demons!” Taro shouted.

His father laughed. “Good boy, Taro!”

The pheasant requested a dumpling and joined the little party.

When they finally reached the ocean, they found a boat and sailed across to the terrifying island of the demons. The pheasant flew up over the demons’ castle and returned with advice on how to get in. Momotaro and his three friends stormed the castle and battled the demons in picture after picture, both frightening and funny.

The kamishibai man’s demon voice sent shivers up Taro’s back. He clutched his father’s hair and held on, trying to be brave.

Finally, Momotaro was triumphant! He tied up the demon king, loaded the boat with all the stolen treasure, and returned it to the people to whom it rightfully belonged. At last he headed home with his friends to where his worried mother and father were waiting. Momotaro had great wealth now, thanks to the ancient treasures of the demons, who were forever forced to do his bidding. He set them to work washing clothes and gathering wood, so his parents never had to work so hard again.

The children cheered and clapped. Taro clapped so hard he almost fell off his father’s shoulders.

“Okay, Taro,” Father said. “I am going to watch the news slides, and then we must get home, okay? Can you play quietly?”

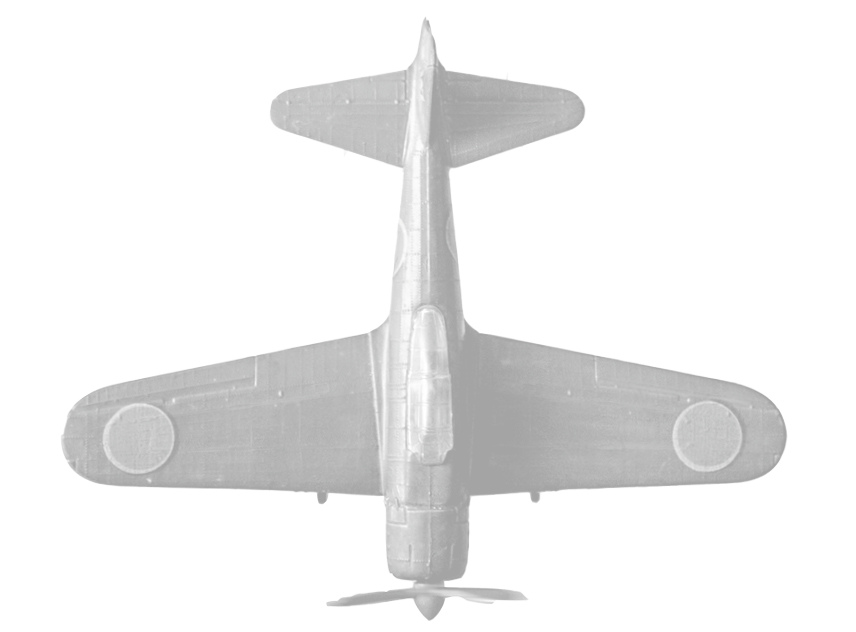

Taro nodded, but on the ground he was just a little person in a sea of big legs as the adults moved in to see the stories they liked most, the ones about problems like money and war. These slides were boring—marching soldiers, gray tanks, and aeroplanes. Father made aeroplanes like the ones in the news. But there was never a single giant demon in sight.

Now Uncle’s voice sounded like the ones on the radio, commanding and fast, nowhere near as funny or perfect as his monkey and pheasant. Taro sighed as the kamishibai man rattled off news of a victory in China, securing more land near the Great Wall. A terrible earthquake and tsunami in Honshu in the far north of Japan. Momotaro would have stopped the tsunami, Taro decided. He’d have had the pheasant flap its wings until the waves turned the other way. Or maybe he and his friends could build another wall, like the one in China, to hold back waves from the sea.

The other kids wandered off to play games at home. Taro stood alone, unable to see past the wall of kimono and suit pants. The candy was still sweet in his mouth, but lonely—he was sure—for the candy in his father’s pocket. He wondered if he could find it without bothering Father, but Momotaro would never do something without asking his parents first. Taro wouldn’t either.

At long last, the news story ended. Some of the grown-ups cheered, but others grumbled about the war. Father, looking satisfied, said it was time to go home. Taro was so tired, he dragged his feet on the cobblestones, his legs heavy.

And then he heard something—a voice like a singing woman, like a bird, calling to him. Like the pheasant in Momotaro’s story. With a gasp, he dropped his father’s hand and set off to find it.

Trip-clop! Trip-clop! He ran up the street as fast as his short legs would carry him.

“Taro! Taro! Where are you going?” his father cried.

Taro smiled. He was going to catch the demons! But first he would need new friends!

Trip-clop! Trip-clop! He ran as fast as his new clogs would allow. The geta were slippery and loud, drowning out the sound he was trying to follow, that high sweet voice singing to him.

Trip-clop! Trip-clop!

He could hear his father coming after him, catching up on longer legs. And now, something else. The straining plings of music. The blind man on the corner nodded to Taro’s wake. Father was more appropriate. He stopped and paid the koto player a small coin.

Trip-clop! Dash!

Taro skidded to a stop on the corner. He closed his eyes and listened.

There—above the music of the blind man, a woman was singing. No, a bird! A nightingale, but such a long, sad sound.

“Taro! What’s gotten into you?” His father was breathless.

“The bird!” Taro said, pointing.

In a window above them, in the narrow lane, a man was drawing one arm across the other. Petting the bird, Taro guessed, for that must have been the source of the singing. And when it sang, Taro went flying up into the clouds, like the bird itself. Better than an aeroplane with its rattle and hum. Better even than make-believe, because it was real.

But then his father was laughing, like falling rocks, bringing Taro back to earth.

“That’s not a bird,” his father said. “It’s an instrument, like the shamisen, from the West. It’s called a violin.”