CHAPTER 19

TARO

Spring 1944

Taro watched Hakata Bay disappear from view as the train trundled toward his new home. Even Nakamura sat in reverent silence. Tachiarai Army Flying School was south of the city of Fukuoka, on the northern tip of Kyushu. It was there in the thirteenth century that Mongols attempted to invade Japan. But the gods chose to protect the home islands, blowing the invaders back out to sea with the kamikaze, or “divine wind.”

Now, instead of wind, the Emperor sent aeroplanes. Taro sat a little straighter at the thought.

“Hey! Girls!” Nakamura broke the silence. Heads turned. Sure enough, there were girls standing on a hillside above the tracks as the train slowed round a bend. “Ah, too young.” He scowled.

“What are they doing?” one of the boys asked.

“Drills,” another replied with a shove. Taro swallowed a sudden feeling of sorrow. They were elementary schoolgirls, each with a sharpened bamboo pole. A teacher stood before them, shouting instructions Taro couldn’t hear. The girls stood at attention, raised their poles, and thrust them in unison at an invisible enemy.

“My mother told me the women in our mura also train like this,” he said quietly. When he had finally asked, after his graduation, she had been proud of her calluses. She was ready to defend the home islands against the gaijin invaders to the end. “The day after Pearl Harbor, my old schoolteacher said this conflict would be over in months. He claimed the Americans would beg for peace on our terms.” Taro ran a hand over his short hair. “I wonder what he thinks now.”

The train rumbled on, past the girls with their makeshift weapons and determined faces, moving steadily toward its destination.

A few minutes later, one of the COs ordered everyone to close their window shades. “Troop movements are top secret,” he said. “It won’t do to have you waving at every schoolgirl in the prefecture.”

The boys sat soberly after that, the darkened windows like a wall between them and the life that came before.

“They better put me in a plane quick,” Nakamura declared. “We’re going to win this war.”

Blue sky, dust, and the scent of aeroplane fuel greeted them as Taro and the other cadets assembled for their first roll call.

“Welcome to Tachiarai Army Flying School! I am your squadron leader, Lieutenant Saito! You will be divided into flights of twenty, two flights to a squadron. You will bunk together, mess together, train together. What is the duty of a soldier?”

“Loyalty!” the cadets shouted. It was the first tenet of the Imperial Rescript for Soldiers and Sailors. They would be expected to recite it, start to finish, whenever an officer demanded.

“Loyalty,” the squadron leader repeated. “That’s correct. Now, when your name is called, line up before your assigned barracks. You will be given two uniforms and a flight suit. You are soldiers now; you will dress as soldiers. Swords are to be worn at assembly. Do not shame yourselves.”

With that, Saito turned on his heel and strode off.

“Akama Toshiro!” the flying officer in front of the first barracks called. Taro waited as boy after boy accepted his clothing and joined the formation in front of his new home. Watching the new faces lining up, Taro began to feel a bit homesick for the familiarity of Oita. Fortunately, when his name was called, he and Nakamura were once again teamed together in the same flight. Dismissed, they were allowed to settle into their bunks until it was time for the evening meal.

“What a dump!” one of the boys exclaimed. The barracks were underwhelming. Inside, the wooden walls were dusty and unpainted. What paint there was on the exterior had begun to flake in the sun.

“It’s not so bad!” Nakamura declared, claiming a bed in the middle of the row. There were ten cots on each side of the narrow room. “At least there are no spiders.”

Taro noted the cobwebs in the corners. “Don’t get ahead of yourself, Nak,” he said. “Maybe there’s a broom we can borrow.”

“And a bucket and a mop and a can of paint,” Nakamura added. “See? Stick with me, Peach Boy! We’re gonna do just fine.”

At 0600, Taro woke to the call of a bugle playing reveille. He rose with the nineteen other cadets in his flight. In unison, they rolled up their sleep sacks and stored them in their cubbies before washing and dressing for the day. Even though it was called flying school, much of it took place on the ground. The army didn’t have enough fuel to waste on untrained pilots. And so, despite the brown silk summer flight suits that had been handed to them on arrival, they mostly wore their drab uniforms and fell into a routine of military instruction— calisthenics, fencing, and martial arts—along with aviation mechanics and meteorology in the morning, and navigation, communications, and “flight training” in the afternoon. Then there was dinner, study time, and curfew at 2200. Once again, there was little time left to practice violin. The call of the bugle to wake, to mess, to assemble, and to sleep was the only music he heard.

“Flight training” meant the cadets built their aeroplanes before they flew them—detailed models intended to teach them how the aircraft worked. Taro was reminded of the hours spent with his father as a boy, carving lightweight wood into struts and wings. This model of aeroplane was newer, but it took the same amount of time and care.

Nakamura couldn’t do it.

“Aaagh!” He threw a pile of sticks across the room like an old man reading I Ching fortunes. “I’ve glued my fingers together again.”

“We can’t fly until we know our planes inside and out,” Taro chided him. “You’d better not wash out over this and leave me here alone.”

Nakamura grumbled and groused as he picked up the wood again.

“Fine. Show me how you did this.”

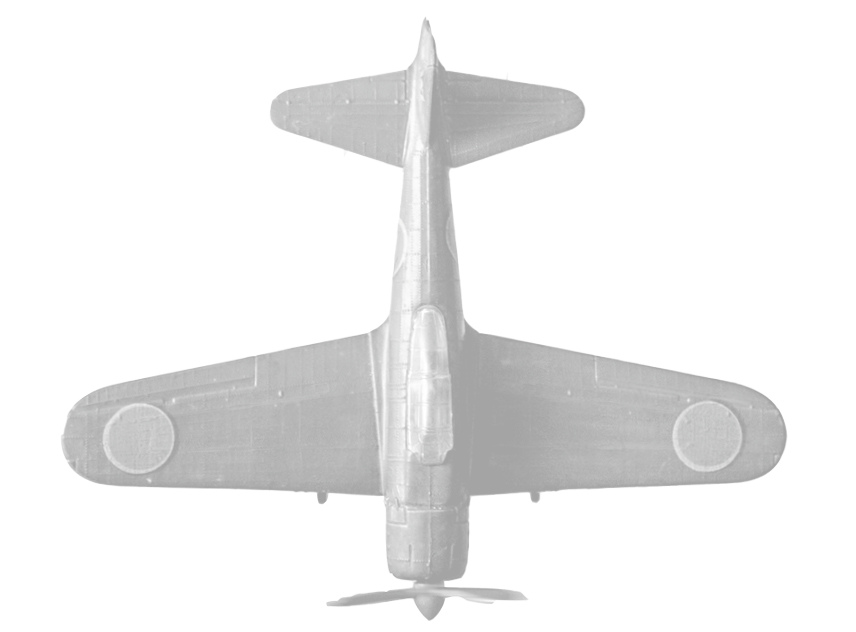

When the models—miniature Ki-9 trainers two hand spans long—were complete, their company graduated to simulators.

“Finally, a flight suit!” Nakamura crowed the first morning, smoothing down the silk jumpsuit. It was a hot summerlike day, and the thin fabric stuck to their sweat in places like a second skin. The fit was a bit snug across his broad shoulders, but he wore it proudly. “I saw some Ki-55s on the airfield this morning. Maybe we can at least sit inside them today.”

Taro patted his friend on the shoulder. “Don’t count on it,” he said. The Tachikawa Ki-55 was an advanced trainer. Nakamura was asking to run before he could walk. “And don’t forget your model plane.”

Taro was right. The simulators weren’t aeroplanes. Not even full fuselages. Nakamura groaned when the flying officer introduced them to the device. It was nothing more than a seat on a sled with a rudder and control stick attached in front.

“Nakamura,” the instructor said, “you’ve been so eager; you get to go first.”

Taro swallowed his smile as Nakamura shuffled into the seat.

“You have your aeroplane?” the instructor asked. Flying Officer Akagi was a thin man with an equally thin mustache. His uniform was always pristine. Taro had decided this was the man to emulate at Tachiarai. He stood straighter now, determined to learn from any mistakes Nakamura might make, to prove himself from the start.

“Sir!” Nakamura held his model aloft. It wasn’t the prettiest version of a Ki-9, but it was sturdy and accurate—unlike the seven other models he’d thrown across the room before this one.

Akagi used a bamboo switch to point out the controls on the simulator—how the levers controlled the throttle and flaps, how to make turns.

“Cadet! You will make the proper actions with the simulator and adjust your model in accordance with those actions, as if it is in flight. You bank left, it banks left. Like so—” He grabbed Nakamura’s wrist, twisting it so the little model tilted left. “Understood? Now, prepare for takeoff!”

Nakamura jumped, then mimed going through takeoff procedures, his model still in his left hand.

“Bank left!” Akagi shouted.

Nakamura pulled the joystick to the left, tilting his aeroplane model in the proper direction.

“Bank right!”

Nakamura banked right but forgot to move his model as he managed the controls.

“Wrong!”

The bamboo switch came down suddenly, slicing an arc of red across Nakamura’s cheek.

Taro flinched, but Nakamura did not. “Hai!” he shouted, correcting his model. From then on, he followed Akagi’s instructions more closely, but still earned two more cuts of the switch before he was done.

Nakamura returned to the line silently, blood running down his cheek. Akagi sneered at the cadets. Taro stared over the flying officer’s shoulder, unwilling to show him any emotion.

“This is not grade school, children! This is the Imperial Army! What does the soldiers’ Rescript tell us?”

“The soldier and sailor should consider loyalty their essential duty. Who that is born in this land can be wanting in the spirit of grateful service to it? No soldier or sailor, especially, can be considered efficient unless this spirit be strong within him—” the cadets began. Some officers allowed them to recite only the highlights, but they were learning Akagi was a harder sort. Word for word, he drilled the Emperor’s wishes into their hearts day and night.

Akagi cut them off before they could continue. “That’s right! If you fumble, drop your model, treat it as a toy, are you of use to the Emperor? No! Your spirit is weak! You are less than useless! Remember what his Imperial Majesty says! ‘We rely upon you as Our limbs and you look up to Us as your head.’ What do we do with an arm that is useless? We cut it off!”

Akagi regarded the line of boys before him. Taro could feel the sweat building on his top lip, his neck. He willed it away. Beside him, a drop of blood fell from Nakamura’s cheek onto the ground. His first blood shed for the homeland. Taro gripped his model. He would not fail.

“All right, then,” Akagi said. “Next!”

Cuts, slaps, and punches. Those were the rewards for nervous fumbling. By the end of the day, no cadet was unscathed. In addition to the cut on his cheek, Nakamura had red marks up and down his left side beneath his flight suit. Taro had welts on his cheek and one hand. He had grown up doing just such maneuvers and received two lashes when he forgot himself and started making engine noises to go along with the motions. Still, Akagi had given him a begrudging nod when he finished his simulated flight.

“Do we have Akagi for all our training?” Nakamura moaned as they got ready for lights-out.

“I hear he came up from infantry,” one of the other boys said. “They’re rough over there. My brother has a friend who says they regularly punch cadets in the face! I guess we’re pretty lucky.”

Nakamura snorted, touching his wounded cheek tenderly. “Yeah, lucky I’m so pretty, or I’d regret this. Eh, Taro?” He threw a grin across the room. “I hear girls like scars.”

Taro’s class graduated to new simulators, ones that were attached to wheeled platforms. The boys would push with all their might, propelling the devices along one of the runways to simulate the feeling of flight. Flying Officer Saito took over for this training. He was a jovial type and not so hard to please as Akagi.

“Are we ever going to actually sit in a plane?” Nakamura wondered over dinner a couple of weeks later. Spring was warming toward summer, but the excitement of being at Tachiarai had begun to cool, replaced by a nervous tension. “We only have nine more months to get up to speed. My brother says when he joined up, cadets got two years.”

“Wow.” Tomomichi, a round-faced kid with spiky hair that no comb could control, almost choked on his rice. “Two years! They probably spent four months just building models!”

“Ugh. I hadn’t thought of that,” Nakamura groaned. “Fine. I can handle a couple more weeks. But I can’t wait to fly.”

But there was more to ground school than models and control panels. They had to learn how to handle maneuvering in the air, which was a lot different from being pushed along the ground by five sweaty boys. For this, they trained in a large Ferris-type wheel, like a metal hoop made from a ladder. The trainee stood inside in a shape like an X—feet braced against U-shaped cross bars, hands grasping a second set above his head—while his classmates rolled him along so that he twisted upside down, sideways, all the directions an aeroplane could go. It was dizzying and, worse, nauseating. More than one trainee emptied his stomach in that gizmo.

Only after Lieutenant Saito saw that each cadet could manage it without getting sick did he announce, “First flight’s tomorrow. You’ll each go up with me or with Flying Officer Takei. Get a good night’s sleep. Write your families. Tell them what you are doing, and that it’s dangerous. There are no guarantees once you’re in the air. Such a letter is good exercise for your moral fortitude. Besides, if anyone screws up, I don’t want to be the first to break it to your mothers.”

With that vote of confidence, the boys were released for the evening.

“Ah!” Taro scooted back in his bunk. Nakamura’s face loomed overhead. “What are you doing?”

“Are you ready?” Nakamura whispered in his indoor voice.

“What time is it? Did I miss roll call?”

“Nope. It’s”—Nakamura grabbed Taro’s wrist—“four a.m., according to your fine timepiece.” The watch had been a surprise gift from Taro’s father, delivered by army packet to Tachiarai shortly after Taro arrived.

“Why are we awake?”

“It’s first flight day, son! Step one in becoming an Eagle of the Eastern skies!”

Taro’s head felt like a sandbag. He yawned, making his ears pop. “Sounds like a movie.”

“Yep! The one they’ll make about us, just as soon as you put on some pants.” Nakamura’s indoor whisper was getting louder. The other trainees were beginning to stir.

“You’re not going to let me go back to sleep, are you?”

“Nope. Come on, I’ll buy you a cup of ocha before reveille.”

Taro was going to be sick. The tea had been a bad idea, and tea had never been a bad idea. So he had to admit it was nerves, not the ocha, churning his stomach while he waited for his chance to fly.

He and the other trainees stood on the flight line at the edge of the runway, a green field stretching out behind them. Nakamura had already taken off, swaddled in the front seat of an old biplane, while a senior pilot took the helm from the back seat. So far, three of the boys had thrown up, and that was just as passengers.

“Kannon, please let me make my father proud,” the boy next to him muttered, a prayer to the goddess of mercy. Taro’s hands grew clammy, and a sheen of sweat sprang out on his top lip. His father was a pilot, an aeronautical engineer, no less. What would he say if his son lost his lunch on the first day of flying? Yes, he’d flown before, but that had been years ago. This would be his first flight without the safety of his mother’s lap. The thought of flying that way now made him smile.

“Inoguchi, next!” the instructor called out.

“Hai!” Taro approached the idling plane, careful to avoid the propeller, and hauled himself up into the open cockpit. The Ki-17 was a biplane—with double-decker wings and room for two fliers seated one behind the other. Once Taro was seated, the instructor pilot shouted at him to attach his earpiece to the speaking tube.

“Hai!” he said into the funneled mouth of the tube by his side. He buckled into the harness, pausing to attach the emergency release to his parachute.

“Watch your feet!” the pilot said through the speaking tube. “Don’t touch anything. Feet off the pedals. I’m in control here, got it?”

“Hai!”

“Parachute attached? Buckled in?”

“Hai!” Taro shouted to each question. And then the plane was rolling.

He listened to the basso rumble of the plane, the increasing tempo of the wheels along the runway, ta-lok, ta-lak, ta-lok. It reminded him of something. The percussion, the bass. Boléro by Ravel. The music swelled inside him, pulling him along on a caravan of sound until the drums dropped into silence and they were in flight. Oboe and clarinet called like songbirds. The world fell away from his feet, and he was swallowed in blue.

Taro wanted to spread his arms out to his sides, above the walls of the narrow cockpit. He wanted to open his mouth and bellow along with the engine, the wind, the rush of noise.

It wouldn’t do to keep this foolish smile on his face once they landed. He could imagine his father’s disapproval.

This was serious business, he told himself.

But the smile remained.

“I told you,” Nakamura said that night as the newly christened pilots toasted each other with shōchū from Lieutenant Saito’s private stock. “We were born to fly!”