“We think everybody should be subjected to us, whether they like it or not. A lot of bands and people have an attitude of, ‘OK, we’re going to have our little crowd here and we’re gonna keep certain people out... We’re gonna have our own private club.’ And that’s bullshit. Everybody should be dragged in and subjected to it. Go out and make an effort - hit people in the head, whether they like it or not.”103

“Have you ever tried to mic up a 100-megaton blast?”104

The violence that surrounded Black Flag - real and sensationalised, cop-provoked or not - was the focus of the group’s first national media attention, and that violence seemed very often the sum substance of the ‘story’; their energising positive influence on a generation of Californian teens, and indeed their thrillingly vivid and disarmingly sophisticated music, was often ignored in favour of the lurid, attention-grabbing ‘scandal’. The ‘message’ - not some politicised diktat from a fascismo punk-rock figurehead, but the earnest, honest, vulnerable and confused self-expression of Greg Ginn and his bandmates - was mostly lost, or perhaps purposely misplaced, amid the noise. But Black Flag would be heard, on their own terms. They would, however, have to take their noise to the people themselves, in the most primitive fashion, and make converts to their cause one punk at a time, conducting group baptisms in the teeming mosh pits in bars and halls and basements across America.

The group was operating in an era before the live circuit that modern indie-rock groups today take for granted, the network of supportive venue owners dotted throughout the great US expanse (which Black Flag themselves helped construct) not yet in place. Booking a tour was a more complex operation than getting your agent to set up shows at a familiar run of venues in all the major college towns. Without this structure already in place, Black Flag had to rely on the DIY mind set of its two leaders, Greg and Chuck, who sketched out a vague pathway across the country, and then tapped every contact at their disposal to ensure enough shows along that trail. The meagre funds they would receive for playing these shows would keep the show on the road, would pay for fuelling their van, and maybe even fuelling the band members too, so they would book as many shows as humanly possible, for literally anyone who would let them play.

The duo stitched together their road map of feasible and friendly venues in a painstakingly manual fashion, developing contacts with fanzine writers, record labels and punk groups as far afield as they could, and sharing whatever information they accrued, to help build this national hardcore punk scene from the bottom up. Vancouver punks DOA, who’d already begun to tour mainland America, were a key influence on their operations, as were their San Francisco friends, The Dead Kennedys, and as the group began to tour, they forged many more friendships with kindred bands operating far from Los Angeles.

“We did a lot of networking, a lot of sharing information,” explained Greg Ginn to Michael Azerrad. “We’d find a new place to play, then we’d let them know, because they were interested in going wherever they could and playing. Then we would help each other in our own towns.”105

“Black Flag set up the network,” says Tim Kerr, then guitarist with Austin punk pioneers The Big Boys, who became friends with Black Flag after the group played local club Raul’s, during their first national tour later in 1980. “They had the names and numbers of all the people who put on shows, and they told you who was great, and who you shouldn’t mess with. They pretty much wrote the book on that stuff, and everyone else would add to it. Everybody was pretty close knit back then, even though America’s so spread out. You kept up with the scene through the records and the fanzines; if you went on tour, you’d bring the newest fanzines from your home town, and give them out to people, so they knew what was going on there.”106

“Chuck Dukowksi, with his fuckin’ phone book, built that same route that we all tour on today,” adds Mike Watt, whose Minutemen would soon hop on as passengers to the Black Flag tour van, playing support to their labelmates. “Eventually, the rock’n’roll clubs got into it, but you could book, say, the Ukrainian Hall somewhere for $200. You didn’t need tolerance from the square johns, these supposedly ‘hip’ people who were booking the clubs. Go on tour, the guy who’s putting on the gig probably plays in the opening band, and probably runs his own fanzine, and you can conk at his pad... It’s all about this shit. A sense of community, big time; you wouldn’t know what was going on in a town without it.

“Hardcore was way different from the Seventies punk scene. It wasn’t gonna just be about New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles; there were scenes all over. That’s the thing about Black Flag - they were the one punk band going all over the place. The kids in Shreveport, or Boise, or Bellingham, places like Philly or DC or Austin... They all saw ‘em.”107

Their low- or no-budget approach precluded the luxuries and excesses touring rock bands in the mainstream had become accustomed to; while Led Zeppelin and Fleetwood Mac toured the world in private jets and fleets of limos, conducting after-show bacchanals in the finest hotel suites, Black Flag’s conditions were infinitely less glamorous. Often, the exhausted and bruised musicians, and their skeleton road crew, would snatch sleep huddled head-to-toe with their touring companions, on the floor of a fan or fellow musician’s home or, if they were unlucky, snuggled up against the amps and instruments in the back of the van.

“Black Flag left in the van after the shows for the next gig, or they slept in the van while the Mugger and Davo [another key Flag roadie] would drive on to the next venue,” remembers Joe Carducci, who would soon become intimately familiar with Black Flag’s modus operandi, with his installation in SST. “If the gigs were close enough to friends they had, they’d stay at a house, but it was still just sleeping on floors; no one had eight spare beds for the whole touring party, so they could live normal for a night. Touring is hard,” Carducci adds. “It’s an unusual, strange thing to do.”108

The Flag began their brutal expeditions across America in the winter of 1980, advertising their Creepy Crawl in the pages of Outcry ‘zine with the first edition of a Black Flag newsletter, entitled The Creepy Crawler. The two-page blurb reprinted a number of Black Flag lyrics, including ‘Revenge’, ‘Depression’, and ‘Police Story’, a blunt and realistic take on the punk scene’s uneven conflict with the authorities, which seemed to reach an inversion of The Doors’ ‘Five To One’ rallying cry, a kind of “We got the numbers / But they got the guns” shrug, bitterly concluding “We can’t win, no way”. The newsletter contained another volume of verse - a paranoid and venomous screed at all who sought to bad-mouth the Flag, entitled ‘To Whom It May Concern’ - which the group proclaimed as “Not a song lyric, but an attack directed at people whom we consider to be ‘yellow journalists’, or assholes.”109

The newsletter included a list of shows the group were planning to play throughout December, beginning in Phoenix, Arizona on November 30, and continuing through a bunch of shows in Texas, a stop in New Orleans, a hop though the Midwest via Chicago, Milwaukee and Minneapolis (the show in Madison, Wisconsin had already been cancelled “due to fear of ‘punk violence’”), and sets in New York, Boston and Washington DC, several of which, the small print admitted, were “not absolutely confirmed yet”. Dedicated to “those who wish it was an act: The HBPD [Hermosa Beach Police Department] and our parents”, the newsletter also advertised that “Black Flag would like to play at High Schools and Colleges. Give us a call if you would like to try to get your school to have us. If they don’t go for Black Flag, call us something else and say that we’re new wave or whatever”.

The December Creepy Crawl was also advertised by a poster designed by Raymond, a jagged, brusquely sketched pencil drawing of a bearded and horned, pointy-eared devil blowing heart-shaped smoke rings with his forked tongue. The rejigged tour itinerary now opened on December 1 at Tucson venue the Night Train, the Phoenix date having fallen through; ultimately, more shows would be cancelled, including much of the East Coast sortie. Still, this tour - and the ones that followed in early 1981, retracing their steps and playing the towns they’d missed first time around - would prove a crucial learning experience for both Black Flag and the nascent American hardcore scene: the audiences discovered the dynamic, delirious live power of Black Flag’s music, while the Flag themselves became properly acquainted with all the thriving new local scenes spotted about the country. They met the promoters booking the shows, they bedded down alongside the groups playing the shows, they were interviewed by every local ‘zine that waved a dictaphone in their direction... The result was an exchange of energy, ideas and excitement that was emboldening for the Flag, and for the scene at large.

On Thursday December 4, 1980, the tour van stopped off at Raul’s, a nightclub in Austin, Texas that served as hub for a thriving local punk scene. An egalitarian, liberal oasis within the resolutely Red State of Texas, Austin boasted a punk scene that was creative, wild and offered a wide open cultural embrace; the singers with two of the city’s three main punk bands - Randy ‘Biscuit’ Turner of The Big Boys, and Gary Floyd of The Dicks - were openly gay, while Dave Dictor, frontman for The Stains [not related to the East LA group The Stains, who later recorded for SST] and later Millions of Dead Cops, was later identified as a transvestite.

The groups on at Austin were radically inventive, and fearsomely political. The Dicks surfed face-slam riffs with blackly sardonic lyrics, their anthemic ‘Hate The Police’ sung from the perspective of a racist, idiot cop (Seattle’s Mudhoney would later cover the song to sneering perfection), while the sharp satire and blunt polemics of MDC lyrics like ‘John Wayne Was A Nazi’ and ‘Corporate Death Burger’ leavened their often-Neanderthal (but always effective) riffage. The Big Boys, however, were operating on another level entirely, guitarist Tim Kerr claiming they didn’t play ‘punk rock’, but were instead involved in some sacred DIY self-expression, which took the form of pit-friendly party-rock and horn-drenched funk-punk, Texan kindreds to the similarly ecstatically eclectic Minutemen.

“Black Flag played at Raul’s a few days after Fear first played Austin,” remembers Kerr. “They stayed with us at our homes. None of us really knew about them, except for our friend, Mike Carroll. He was always reading all the music magazines, he knew all the stuff going on in England and LA.”

Kerr remembers the initial onslaught of Black Flag as being a disorientating experience, a full-on rush that allowed precious few pauses for breath. “We made a cassette of the show, straight off the mixing board, and I remember listening to the tape the next day, and not really being able to distinguish anything, other than a bunch of craziness going on. I remember, though, literally two months later, going back and listening to that tape, and recognising all the songs.

“Black Flag, when you first saw them and hadn’t heard their stuff before, kind of came off more like this barrage of noise, and you couldn’t really tell what was going on. There was obviously a beat, a rhythm happening, but... Fear had more regular ‘songs’, but Black Flag came off like a ‘happening’ on the stage. But once you knew their style and their songs, it made a lot more sense. Fear were pretty straightforward punk rock; Black Flag definitely had the chaos going on. They were more intense, because of what they were singing about, ‘internal’ things that, when you heard them, affected you. Like, yeah, I’ve got that problem too. The pit would be a lot more intense when they were playing. A band like Fear was more just funny songs, it wasn’t something that would really affect you. Black Flag weren’t ‘political’, but their songs had a lot more to do with what was inside of you, as opposed to what was going on around you.”

The Big Boys befriended Black Flag after the show, and the Californians went back to sleep over at the Texans’ houses, before setting off the next day, for the next town and the next show. “Dez had been pacing back and forth at the front of the stage, and he looked like Pistol Pete Maravich, a basketball player from Louisiana State University,” laughs Kerr. “For a while, we had this running joke, where I’d call him Pistol Pete, and he called me Terry Bradshaw, because he thought I looked like the footballer.” The impact the Flag made on The Big Boys was powerful, and would resonate deeper with each subsequent trip the Flag made to Texas. Certainly, today, Kerr doesn’t underestimate the impact of Black Flag, and their touring example, on his life and his art.

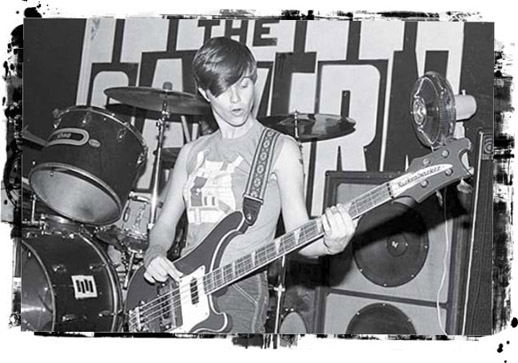

“I got the Black Flag bars tattooed on my wrist sometime in 1981, I think,” Kerr says, the first of many tattoos he would acquire over the years. “People were getting things like ‘Rise Above’ tattooed on their arms, and I wanted to get something on my hand, but the guy wouldn’t do it. At that time, there weren’t any upmarket tattoo shops like there are now, just these total motorcycle-gang type of places. I got the bars because Black Flag, along with DOA, basically opened up the doors in America for all this stuff, for all the kids to start playing. It’s a pretty amazing thing, because they were on tour all of the time, and they would play any itty-bitty Podunk town: as long as the place would put on a show, they were there. They’re the people that really rode this thing out, as opposed to just sticking with the ‘cool’ cities. So that’s what the bars represented to me: those guys opened up the doors for me.

“Fear didn’t have that same aim,” adds Kerr, “they weren’t too concerned about building a community. I don’t think Fear really cared one way or another if they played All Ages shows, where Black Flag really did; they wanted to make sure kids had the opportunity to come to the shows. There were a whole lot of places that had never seen a punk-rock show ever, until Black Flag played.”

In Arizona, meanwhile, Black Flag would meet rag-tag local group The Meat Puppets. Led by the Kirkwood brothers, singing guitarist Curt and bassist Cris, the Puppets had no truck with punk purism, and scarcely described their own feral, avant scree as ‘hardcore’. “We were pretty much a punk-rock band, I think,” says Curt. “That was our intention: we tried to play things fast. I think we also liked to play things really shitty; that’s probably what was unconventional about us, we were more in the Germs camp than the hardcore scene. We didn’t take as many drugs as The Germs. We could play our instruments well, pretty much, we just liked to be irritating.”110

The Kirkwoods had discovered punk rock via their drummer, Derrick Bostrom, who introduced them to the calamitous sounds of UK punk, though with typical idiosyncrasy Curt declared a love for Stiff Little Fingers over The Sex Pistols, “because they were funnier. I was into PIL, it was an art thing, Lydon was trying to be a parody of snotty. I got into a lot of other LA stuff too: Black Randy, The Germs, Weirdos... The Plugz were really good. The Dils, I loved them.”

Like The Big Boys, however, The Meat Puppets’ tastes strayed far from the three-chord chugga-chugga blueprint hardcore often clung to. “We were into Seventies art rock, any of that ‘out’ stuff - Henry Cow, even Yes, and I loved Gentle Giant. Any kind of well-played, progressive rock. I liked jazz, I’d go see stuff from Ramsey Lewis to Art Ensemble to Mose Allison; you name it. I saw Thin Lizzy, who were amazing. Lynyrd Skynyrd is still one of the best bands I ever saw. I didn’t have any boundaries. Stylistically we probably ripped off a lot of punk rock, but we were incorporating a lot of earlier influences. I’ve played in bands that had to play Barbra Streisand songs, Steely Dan, Earth Wind & Fire. I’ve played in a hard rock band that played Thin Lizzy covers, I’ve sung Kansas songs…

“We could play music, and some people really liked it, and a lot of people really didn’t, and would leave the bar. When we saw we had the capacity to clear the room, that was amazing. It was like, if you’re not gonna get anywhere, why kiss these peoples’ asses? We opened for a San Diego band called The Penetrators, one of the biggest ‘new wave’ bands, because they were sick of their yuppie crowd. We’d go through women’s purses while they were playing, pour peoples’ drinks on ‘em and stuff, really upset people, and they thought that was funny, because they couldn’t get away with it - they were making good money entertaining people. And we didn’t care, their crowd didn’t like us anyway, they didn’t like our music. We thrived on that.”

After opening for Black Flag on Wednesday March 4, 1981, at Tumbleweeds in Tucson, Arizona, Greg Ginn asked the group to record an album for SST Records, which they would cut with Spot in LA, later that November. The eponymous album, which followed a four-track EP they cut for Arizona indie World Imitation Records that summer, was a frenetic and diverse dash through 14 songs that scarcely resembled the brilliantly unique punk-fried country-psychedelia they’d later distil for SST. Their most ‘punk’ release, the group’s hippie roots were revealed on a handful of covers recorded in the same session but unreleased until almost 20 years later, including Buffalo Springfield’s ‘I Am A Child’, and Grateful Dead’s choogling ‘Franklin’s Tower’.

The Meat Puppets’ wonderfully illogical eclecticism made them a logical addition to the fledgling SST roster; while the hardcore explosion, then at its height, would ultimately deliver a slew of groups who subscribed to the high-velocity three-chord hegemony of punk, with precious little imagination, SST’s signings were a ribald and distinguished bunch, running a stylistic gamut that challenged those who criticised punk as a creative dead end.

“With hardcore came some homogeneity, some orthodoxy,” nods Mike Watt, “and it seemed punk was going the way of all things human, starting to get all ossified.” Watt’s own Minutemen, however, operated in fervent opposition to this received wisdom; their debut album, 1981’s The Punch Line, was the fourth release on SST, delivering 18 songs in 15 minutes. Despite its brevity, the album was alive with energy and ideas, bassist Watt, guitarist D. Boon and drummer George Hurley trading vocals across razor-wire-taut songs that played fractured chicken-scratch guitar against rubberised punk-funk bass, making its fiercely politicised messages with wit and good humour alongside the rancour. It would prove only the first volley of a career marked by barrages of such brilliance.

“Black Flag held an incredible significance to Minutemen,” says Watt. “Nobody ever understood the connection between our bands. We didn’t sound like Black Flag, and we weren’t supposed to sound like Black Flag. We sounded like ourselves, and that’s what they liked. That was the idea. It’s hard for me to imagine a Minutemen without Black Flag, even though our group was so much about me and D. Boon’s personal relationship. But we learned so much from the Flag: copying their work ethic and trying to be creative. We felt inspired by them to find out where ‘the wall’ was by pushing against it, not just agreeing that it’s somewhere. ‘Oh yeah, it’s over there, I heard it from some guy somewhere.’ No, you go over there, and you push. We learned that from Flag.”

SST’s fifth release would feature the Flag themselves. The Six Pack EP was the group’s first release with Dez on vocals; recorded with Hollywood punk face and bandleader Geza X at Media Arts in the spring of 1981, Six Pack led with the Greg Ginn-penned titular track. The song opens with a slow build, as Chuck ekes out a rumbling circular bass line, joined a few bars later by an itchy rustle of drums and, a few more bars on, distortion-fuzzed guitar scratching along to Chuck’s riff, before Robo’s crashing cymbals announce a dramatic surge in tempo, as the song careens off like a beer-charged teen ricocheting about the mosh pit. Barked punker choruses of “Six! Pack!” suggest the song is some Neanderthal party anthem, but the Ginn-penned verses come off like a rewrite of ‘Wasted’, with a much more bitter bile in its bite, parodying a dumb alcoholic’s love for booze above all else; Black Flag at their sardonic, face-crunching best.

‘I’ve Heard It Before’, a Dukowski/Ginn composition, opened with wailing siren guitars over primitive tom-tom rumble, Cadena howling to someone, anyone (no one?), “I don’t need! Authority! Bullshit! Authority!”, before, once again, the song revved up to a helter-skelter slalom, Dez barking this anthem to cynical savvy between hectic and bristling Greg Ginn guitar breaks, the pile-up of notes a jagged zigzag of white noise. Dukowski’s ‘American Waste’ hurtled past at similarly heedless velocity, Greg summoning a scabbed guitar tone that sends hackles rising, matched only by Dez’s paraffin-gargling roar, yelling a broken screed in absolute opposition to the American Dream, expressing Chuck’s own profound discord with the temper of the nation.

Six Pack collected together three of the newest additions to the Black Flag set list, which had swelled greatly since the Panic days. Indeed, Greg’s newest songs were his best, the police persecution seemingly sharpening his acidic wit, and amplifying his potent sense of alienation and disaffection. ‘Room 13’, which shared its name with Medea’s address, was a blood-splattered tumult co-written by Greg and his girlfriend. Over a lurching rhythm and guitars that squalled and screamed like flaring nerve endings, the song depicted an anguished, co-dependent relationship between two outcasts, ever on the edge of suicide. “Keep me alive!” rang the nagging refrain, with a desperation that was compelling. “I need to belong, I need to hang on... It’s hard to survive.”

Ginn’s ‘Damaged II’, meanwhile, came from a similarly bruised and vulnerable place, another dispatch from the edge, offering more abusive co-dependence, and an affecting refrain of “I’m confused / Confused / Don’t wanna feel confused”. While Ginn’s more anthemic tracks might have made for fine fist-pumping fuel in the mosh pit, it was when expressing this profoundly fractured ambivalence towards life - illustrated in this track not least by the line, “Put the gun to my head, and I don’t pull” - his music was at its most unsettling, and powerful. Its prequel, ‘Damaged I’, was a weirder beast that had not quite taken shape yet, a lop-sided stumble into the darker reaches of the psyche.

More powerful still was ‘Life Of Pain’, which seems to offer another angle on the relationship in ‘Room 13’; opening as a lurching, molten-metal slog, its blunt and uneasy riffage backed an urgent lyric that gazed with stricken agony at trackmarked arms, and accusing “You don’t care who you harm”. A desperate attempt at an intervention via song, its mordant chorus of “Self destruct, Self destruct” is chilling, while the pleading verses offer a vulnerability the Flag had previously kept walled up behind metallic guitar noise and a veneer of sardonic lyrical venom. When the group performed the song at Pittsburgh’s Stanley Theatre, on Saturday July 4, 1981, Dez introduced it by saying, “I see many people have developed relationships with needles... This one’s for them. If you’ve ever had a relationship with a needle, you’ll know.”

As the group honed and finessed these songs, on their sleep-starved trips across America, the oft-postponed Black Flag album was swiftly taking shape, an opus heavy with emotional upheaval and interpersonal conflict, delivered in a cathartic blast of static-stirring guitar, axe-juggling rhythm and, thanks to Dez, a diamond-hard bark that delivered every uncompromising word home. But the rigours of touring and regular performance, not to mention the Flag’s still-Herculean commitment to rehearsal and practice, were beginning to take a terrible toll on Cadena’s vocal cords; would he be able to withstand the gruelling miles and the many nights that lay between them and the recording studio?

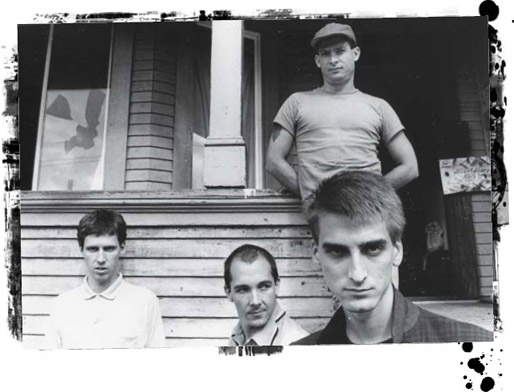

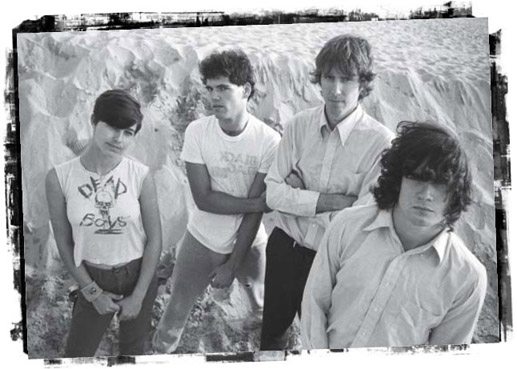

Early Panic rehearsal, 1978. Left to Right: Chuck Dukowski, Robo, Keith Morris, Greg Ginn.

(PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN/COURTESY RYAN RICHARDSON WWW.RYEBREADRODEO.COM)

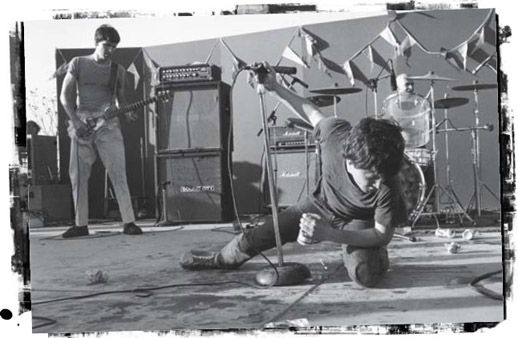

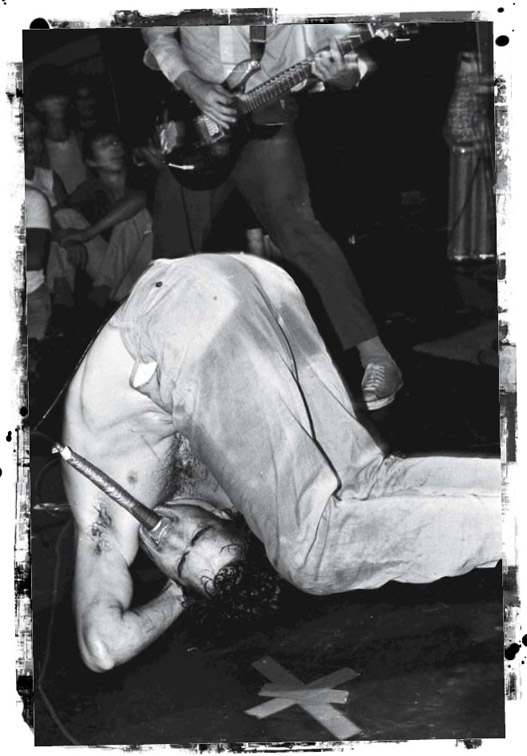

“Maybe sixty seconds into the first song, it began to rain food: sandwiches, half-eaten drumsticks, watermelon and cantaloupe rinds, banana peels,” remembers Keith Morris, of Black Flag’s performance at Polliwog Park in 1979. Here, he ducks the raining missiles of food hurled by offended family picnickers… (SPOT)

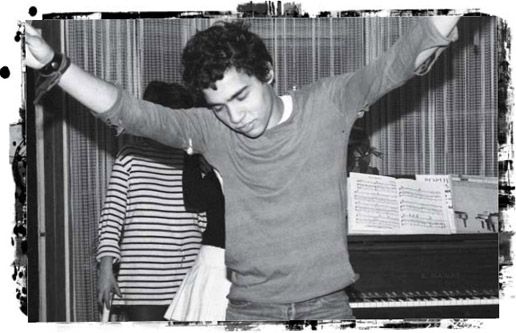

Ron Reyes: “This was taken prior to the release of Black Flag’s second EP Jealous Again, Ron sings on that EP and he asked me to do a photo session for cover consideration. We went to Eve’s mother’s house in a rather nice part of Vancouver and I shot photos of Ron and Agita with Eve and a baseball bat, having found Agita and Ron in the living room in each others arms.” (BEV DAVIS)

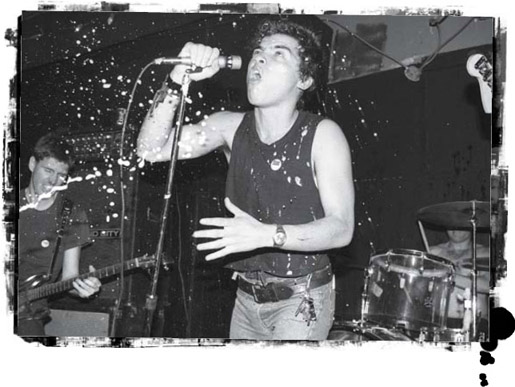

Ron Reyes enjoys a baptism of beer, onstage with Black Flag, April 17, 1980 in Vancouver BC at the Smilin’ Buddha. (BEV DAVIS)

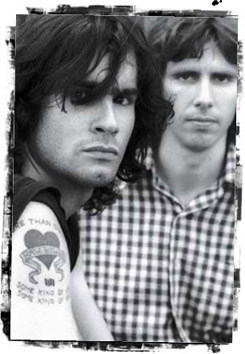

Left to right: Greg Ginn, Chuck Dukowski, Dez Cadena, at the VEX 1981, East Los Angeles.

(GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

Black Flag hanging out in Vancouver, where they played their first shows outside of California. Left to Right: Greg Ginn, Chuck Dukowski, Robo, Dez Cadena. (BEV DAVIES)

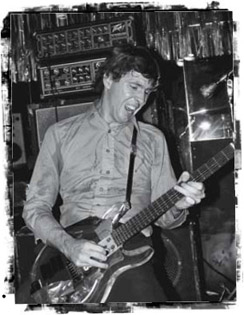

Greg Ginn, Riverside, California: November 21, 1981, armed with his trademark transparent lucite Dan Armstrong guitar, which he modified to withstand the blood and sweat that would splatter it in the course of a Black Flag live show.

(EDWARD COLVER)

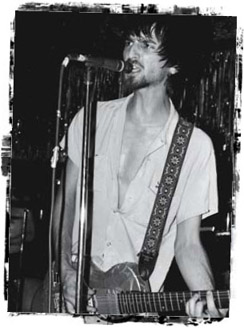

Dez Cadena, Riverside, California: November 21, 1981.

Dez’s skills on rhythm guitar enabled Greg to make good on the concept of a twin-guitar Black Flag, which he’d cooked up during Ron’s last days with the group (EDWARD COLVER)

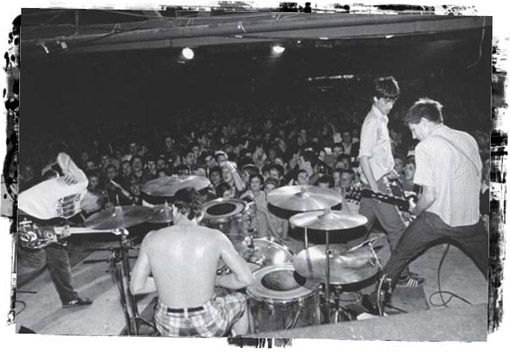

Black Flag at the Stardust Ballroom, Hollywood California 1980 (Dukowski, Robo, Dez Cadena, Ginn)

(GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

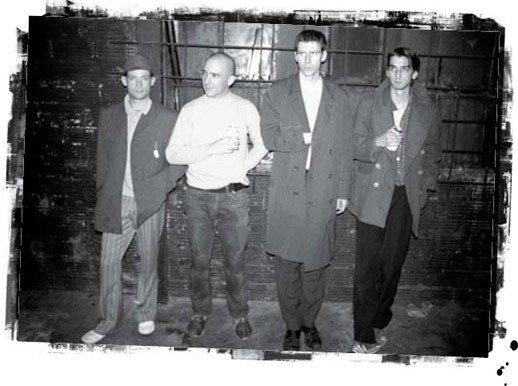

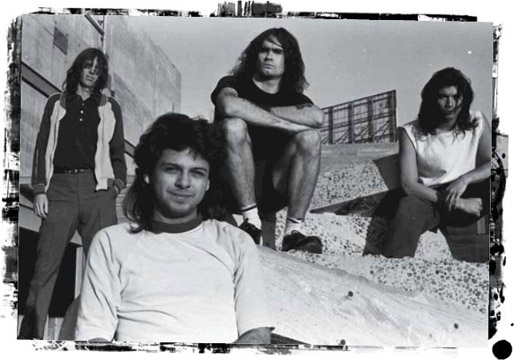

Dressed to Kill: Outside Raul’s Club, famed mecca for hardcore punk in Austin, Texas 1980. Left to right: Roberto ‘Robo’ Valverde, Chuck Dukowski, Greg Ginn and Dez Cadena. (VERN EVANS)

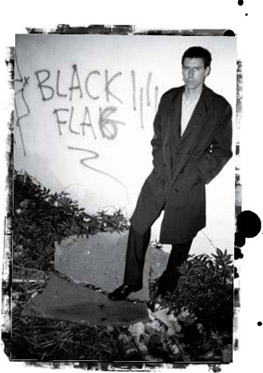

Dez Cadena, the Flag’s third frontman and sometimes rhythm guitarist, plays it enigmatic in an alley in West Hollywood, in this out-take from photos taken for the ‘Louie Louie’ single. The alley is behind Duke’s, near the Tropicana, where Tom Waits lived. (EDWARD COLVER)

Black Flag’s enigmatic leader and guitarist, Greg Ginn, outside Raul’s Club in Austin, Texas 1980. (VERN EVANS)

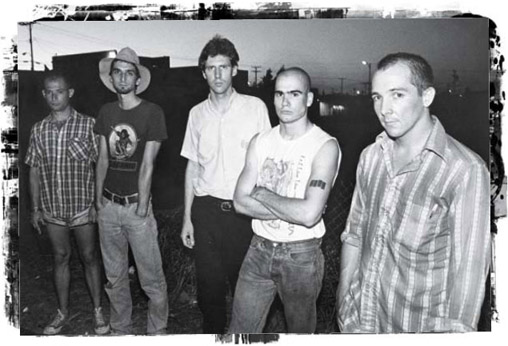

The line-up that recorded the epochal Damaged album, hanging out behind legendary Costa Mesa punk club Cuckoo’s Nest, on the night of Henry’s first public show with Black Flag. Left to right Robo, Dez Cadena, Greg Ginn, Henry Rollins, Chuck Dukowski. (GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

Promo shot of the group circa 1982’s TV Party EP: note the presence of drummer Emil Johnson, whose tour of duty with the Flag would be brief; also note Chuck Dukowski’s provocative Hitler moustache. (GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

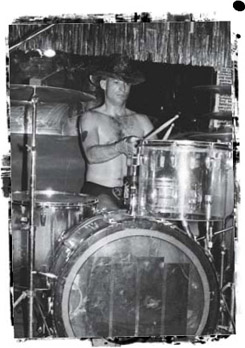

Robo proudly pounds his iconic perspex drum-kit, which would later be painted white by his successor, Emil Johnson.

(EDWARD COLVER)

Chuck Biscuits at the traps, displaying a setlist full of songs the Flag would be legally prevented from recording until long after his exit from the group. (EDWARD COLVER)

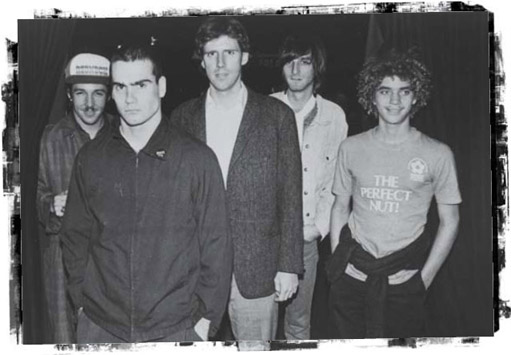

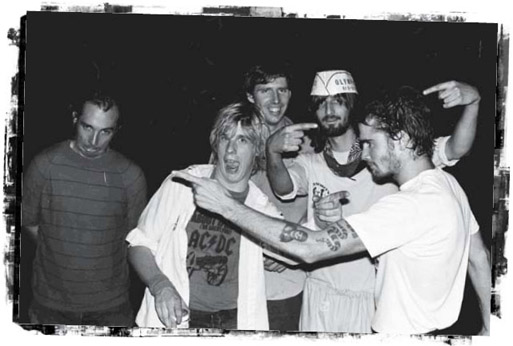

While the Unicorn lawsuit kept the Flag out of the recording studio (and eventually landed Ginn and Dukowski in jail), the group tried not to let it get them down. Left to right: Chuck Dukowski, Chuck Biscuits, Greg Ginn, Dez Cadena and Henry Rollins.

(EDWARD COLVER)

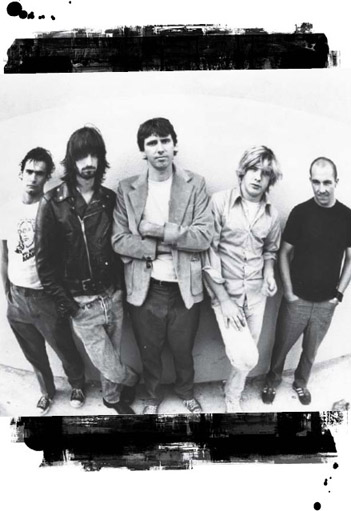

The Black Flag line-up that recorded the legendary 1982 demos (featuring Dez Cadena, second from left, on rhythm guitar and, second from right, drummer Chuck Biscuits) outside the SST office/living space in Redondo Beach 1983. (GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

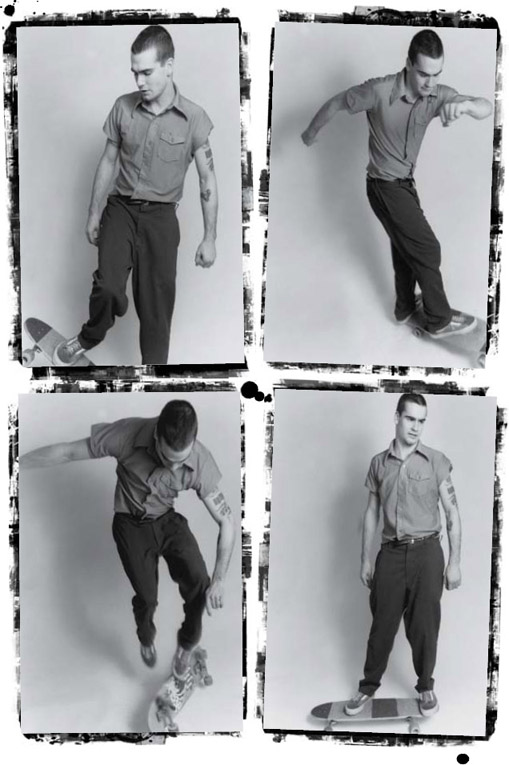

Thrasher: Flag frontman and keen skater Henry Rollins shows off his on-board skills, circa 1980/81, South Bay, California. (ANN SUMMA)

A fresh gash on his right cheekbone, Henry Rollins gets up close and personal with the Flag’s moshpit. San Francisco 1982.

(GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

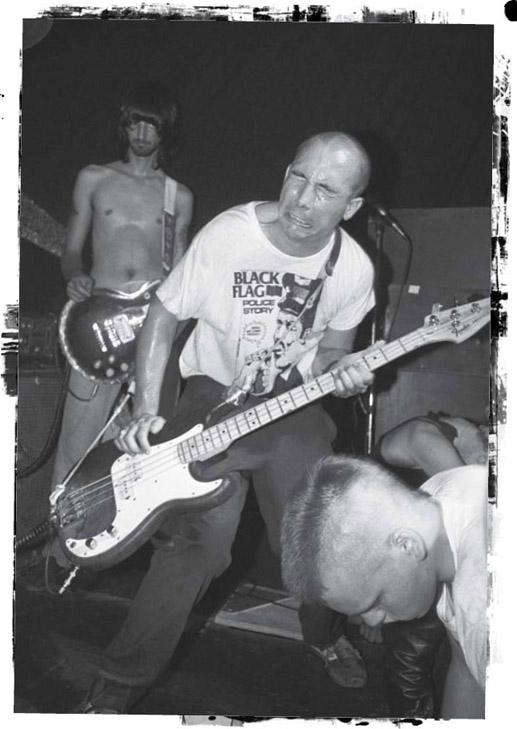

“I thought the bassist was the star, I thought he was the leader of the band... Between songs, he would start pontificating at the top of his lungs, pointing at people in the crowd, with this look in his eye that just radiated fire.” - Tom Troccoli on Chuck Dukowski, Black Flag’s first bassist. San Francisco 1982. (GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

Take It To The Stage: A rare open-air performance from the Flag, with sometimes-Descendent Bill Stevenson on the drum-stool, in front of the Federal Building in West Los Angeles, 1983. (GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

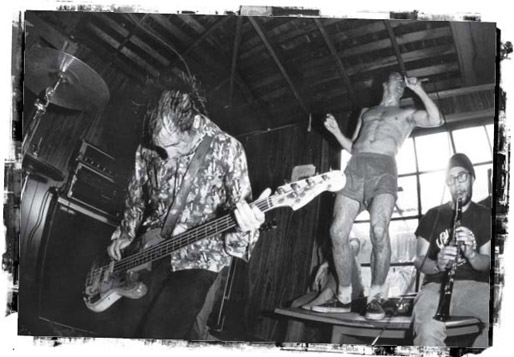

Henry and Chuck jam with producer Spot at a sweaty garage party in Culver City, 1983.

(GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

Black Flag play legendary London punk venue, the 100 Club Oxford Street, during their ill-fated 1981 tour of Europe. (PAUL SLATTERY)

A 1984 portrait of the line-up that cut Black Flag’s final brace of studio recordings: (l-r) Kira Roessler, Bill Stevenson, Greg Ginn, Henry Rollins (GLEN E. FRIEDMAN/WWW.BURNINGFLAGS.COM)

“It was very satisfying to piss off punkers who just wanted to see us do the same thing over and over again, because if people just want to see you play the same songs over and over again, they should stop coming.” - Kira Roessler, the Flag’s second bassist, rings the changes. (BILL WILSON)

The final line-up of Black Flag: Greg Ginn, Anthony Martinez (drums), Henry Rollins and C’el Revuelta (bass), outside the Brewery Art complex in downtown LA. (EDWARD COLVER)

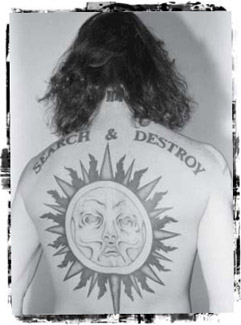

Rollins shows off perhaps the most iconic of his many tattoos; the angry sun image would illustrate the sleeve to Rollins Band’s breakthrough 1991 LP, The End Of Silence.

(EDWARD COLVER)

Henry Rollins and Greg Ginn, London 1984.

(ALASTAIR INDGE/RETNA PICTURES)

Big Ugly Mouth: Henry Rollins, lost in the moment. (EDWARD COLVER)

As the Creepy Crawling continued, through the early months of 1981, Black Flag wandered like a contagious Patient Zero through America, infecting local scenes with their viral ambition, their can-do attitude inspiring nascent local hardcore scenes by their impressive example. Their message was spreading via other media also, however. Their show at the Starwood in Los Angeles on Wednesday January 7, 1981, the second of a two-night stint, was attended by Corey Rusk, a young punker from Detroit who had managed to snag a place on an exchange programme between his school in Michigan and Beverly Hills High School in Los Angeles.

Having already had his mind blown by the Nervous Breakdown EP, Rusk dragged a primitive video camera to the Starwood show and filmed it, taking the tape back with him when he returned to Detroit. While Dave Stimpson and Tesco Vee, two local punk aficionados who ran respected Michigan punk ‘zine Touch & Go, had made it across to the Flag’s Chicago show the previous winter, Rusk’s bootleg video offered Flag neophytes what Todd Swalla, his bandmate in Detroit hardcore group The Necros, would describe as “instant hardcore education!”

“As soon as Corey got back, we were freaking out, watching that video constantly,” added Necros frontman Barry Henssler. “Mugger was acting as stage security, and he had no regard for safety whatsoever. He was clocking people in the face with cold-hearted meanness... And we were into it! Corey hung out with Black Flag and The Circle Jerks while he was out there and got to know them pretty well.”111

Rusk’s tape helped prepare the Michigan kids for Flag’s arrival that March, playing at Club Doobee, a redneck country bar in Lansing, Michigan on Sunday 22nd. Support was provided by The Necros and their Detroit punk compadres The Fix. The group played a long, hard set that wasn’t without flare-ups in the crowd; during a late-set take on ‘No More’, a piledriver thrash Ginn had recently penned that began with tolling bass that slowly wound tighter, along with Robo’s drum rolls, before igniting like a firecracker, Chuck drew out the water-torture intro for three minutes, as Dez engaged the audience in some fierce banter. “Why are you so dirty?” he replies, to a girl in the audience screaming “Fuck you!” and telling the Flag to get out of town. “What’s your problem?” he yells, over jeering and abuse, and criticism of the ‘un-punk’ bass solo.

After the show, the Flag repaired to a house occupied by members of The Fix for a wild late-night party. “Greg Ginn and Dez Cadena cranked out some Beatles and Neil Young on our stereo at that party,” remembered The Fix’s Craig Calvert. “That certainly surprised a room full of punk rockers. I think that might have been the night someone set our couch on fire. I remember the police weren’t so happy about that, and shut the party down.”

Beyond the typical police attention, Black Flag’s debut in Lansing also won them reviews in the local press. Jon Epstein of The Lansing Star raved that, “Ginn, the fastest guitarist you’ll ever see, used his speed tastefully. Standing stationary, his head shaking back and forth, he performed what would normally demand two guitarists... Black Flag finally ended a long, fierce set (I thought at least one of them would have a heart attack) with The Kingsmen’s ‘Louie Louie’; in an ultimate slap at rock’n’roll, they handed their instruments to the clawing audience. As the show ended in a fury of noise and confusion, Black Flag was already off the stage, the night ending in utter chaos.”112

However, Dave Winkelstein, rock correspondent for The Lansing State Journal, declared that Black Flag were “hardly worth the long wait. The vocalist sang with the melody of an angry football coach. The group did show more energy in a few tunes than most cutesie commercial bands show on an entire tour. So did the opening bands, and so does a wounded water buffalo. The musical theme of the night seemed to be bash-bash-bash, crash-crash-crash, who cares if it sounds like trash? Rudeness to the ears and to people shouldn’t be so easily tolerated.”113

Touch & Go reprinted both reviews in full in its 13th issue, and took Winkelstein to task for his anti-Flag sentiments. “Such imagery, Dave,” scoffed the editorial. “Just because you can’t get any ‘punk sex’, your aching weenie forces you to lash out at the whole scene... Get dorked, you paunched-out hippy fucksack. And next time you come to one of our shows, wear a nametag.” Tesco Vee’s own review of the set was similarly salty and succinct: “There were people here from all over, and if you went away disappointed then all I can say is you’re too old, or your personal little set of fucked-up values have left you permanently in need of the cyanide pie.”114

“Black Flag had lit all these fires around the country, they turned the heads of lots of people,” says Joe Carducci, of Black Flag’s maiden voyages across America. “Until they saw Black Flag, these groups didn’t know what was coming. They didn’t know how to do it, how to take your music on the road, how to get it to the people... They didn’t know you could do it... Because when even the Ramones are barely hanging on to a career, what’s possible? And then Black Flag showed everybody: that it was gonna be hard, but also that it was do-able. And that it was fun! I’m sure when Black Flag rolled into town, the lifestyle they were living, and the things that they were doing, made a lot of people realise that they wanted to do it too.”

Another bustling local hardcore scene, one with enough vitality, creativity and ambition to rival even that of Los Angeles, was similarly rabid at the prospect of catching Black Flag play live, having latterly become acquainted with the South Bay scene via the early SST 7”s. Washington DC’s punk scene was still in its relative infancy as 1981 dawned, but already boasted an impressively productive and ethical DIY label in the form of Dischord Records, an imprint dedicated to chronicling the local scene unfolding about them. The label was run by Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson, formerly the rhythm section of combustive DC hardcore group The Teen Idles, who played short sharp songs at bullet speed - their rabid cover of The Stooges’ ‘No Fun’ clocked in at just over two minutes, played at a fevered double-time. They’d since formed upright quartet Minor Threat, MacKaye swapping the bass for the microphone, fronting one of the few groups who could fairly challenge Black Flag for the title of most influential hardcore group of the era.

While his musical background encompassed the same fervent love of Seventies hard-rock icons like Ted Nugent as Greg Ginn and Chuck Dukowski, MacKaye drew much of his influence from another Washington DC band, who had helped establish hardcore’s full-pelt velocity. But while Bad Brains were instrumental in drawing up the brutal blueprint for hardcore, they were unlike any other punk group that ever lived. The quartet, all Rastafarians, had their roots in a jazz-fusion unit called Mind Power, where the musicians honed the fierce chops that would power their later songs at such breakneck speed, and with such fearsome precision.

A growing love for Black Sabbath and The Sex Pistols prompted the Brains’ move away from Mahavishnu-esque complexity, though their own punk-rock songs - carrying fiercely inspirational lyrics inspired by Think And Grow Rich, a self-help manual first published by author Napoleon Hill in 1937 - still obeyed the taut rhythmic sensibility they’d developed as Mind Power. Bad Brains songs threw out punk-rock’s three-chord rulebook, their songs wild and adventurous, fusing the feral intensity of frontman HR’s vocals with a group who changed tempo on a dime, who thrashed at light speed and then riffed-out like Sabbath in a Mogadon haze. And while their set lists were peppered with righteous punk-rock anthems like ‘Banned In DC’, ‘Attitude’ and ‘How Low Can A Punk Get?’, they were unafraid of dropping gear and laying down some heavy-karma roots reggae mid-set.

“Bad Brains were the fastest, greatest band in the world,”115 MacKaye told me, in 2002, recalling a period when his group, Teen Idles, got to learn some crucial lessons in punk rock from their idols, close up. Bad Brains had made an attempt in 1980 to tour the UK, but visa problems saw them sent back to the States with a sizeable dent in their operating capital. In addition, all of their gear had been stolen on their return to Washington DC.

“They were playing soon and asked if they could borrow our gear to rehearse,” continues MacKaye. “We said yes, but we rehearsed in Nathan’s mom’s basement. They’d meet us from our high school and we’d set up in her basement and rehearse for an hour, them sitting on the sofa watching us play. Then we’d all switch places.” He beams broadly at the memory. “Watching them work was so inspirational, it just made me realise the key to everything is to work really hard, and never sell yourself short.”

MacKaye put these lessons into practice in building up the Dischord label, releasing Teen Idles’ posthumous sole EP with the $600 they’d accrued as a band throughout their career. Local record store owner Skip Groff hooked the boys up with a pressing plant, and soon they were throwing its first ‘glue party’. “We did that for the first six Dischord releases. All of them. We hand cut and folded and glued every single one of them. By the end of it, that was probably about 10,000 records,” says MacKaye. “I loved it; that’s exactly how I like to spend my time, working with a bunch of people doing constructive things.”

This same positive DIY spirit characterised MacKaye’s next group, Minor Threat, who finessed Teen Idles’ hectic rattle into a streamlined, devastatingly effective attack, plying lightning-fast songs that welded razor-sharp riffage to a jet-propelled rhythm section, laying down a hurtling, exhilarating punk rock for MacKaye to bark over. His lyrics would soon gain easily as much attention as the music itself; like Ginn, MacKaye penned personal songs concerning only his own experience and world view, but they were nevertheless, like Ginn’s songs, taken by some within his audience as instructions, and interpreted by others as vaguely fascistic exhortations.

Most provocative of a lyric book that took aim at mindless violence, at bourgeois relationships, at the malign influence of prudish mainstream religion, were a couple of songs concerning MacKaye’s abstemious lifestyle choices. ‘Straight Edge’, a cut off their eight-song debut 7”, released June 1981, found Ian identifying himself in stark contrast to the drug-addled, skirt-chasing punker stereotype, unwittingly coining a youth movement of the same name that similarly rejected intoxicants, often obnoxiously so. MacKaye, however, in no way authorised such groups, and indeed swiftly grew tired of having to defend his lyrics against the reactions they inspired within his fan base. Nevertheless, such episodes spoke of the influence MacKaye held upon the DC punk scene. “It was a good thing that Ian was the papa of that scene, morally,” says one-time DC punk Don Fleming, “because Ian had the right moral compass. What happens to a lot of white boy punk scenes is that they just turn to fascism, which is maybe likely wherever you’ve got a bunch of hard-headed guys who wanna bang heads.”116

Glen E. Friedman first met Ian MacKaye at a Bad Brains show in 1981. “His brother Alec’s band, The Faith, were opening up,” remembers Friedman, “and they already knew my photos because they were big fans of Skateboarder magazine. When I got to the show, Alec half-jokingly bowed down to my feet, for the Skateboarder work that I’d done, and introduced me to Ian. We hit it off pretty well; they were so into skateboarding, and seemed pretty nice guys to me. I hadn’t even heard their record yet, I got to hear them later, and became a very big fan. ‘In My Eyes’, off their second single, was the greatest song I’d ever heard up until that moment, that was something really special.”

It was through skateboarding that MacKaye had forged a deep friendship with another kid in his neighbourhood, a young tearaway named Henry Garfield. “We first heard of him because somebody told us he had a BB gun,” MacKaye told Juice magazine’s Jim Murphy. “We started hanging out with him, shooting poker chips and listening to Cheech & Chong records.”117 During the summer of 1974, MacKaye moved to Palo Alto in San Francisco Bay, after his father got a nine-month work assignment there. In the interim, Garfield had fallen out with MacKaye’s other friends.

“So when I came back, Henry was out to kick their asses and I was sort of guilty by association,” remembered MacKaye. “So he was out to kick my ass too. There was a lot of time spent hiding from Henry, cos he was kind of a tough kid. He hated us and we hated him and then one day he was skating by and he saw us with our skateboards and he was like, ‘You skateboard?’ Then we all became friends again. And it was Henry who found out about Skateboarder magazine and he had some of the newer gear. That was when we started learning about what was going on in California: precision bearings, Fiberflex, all these different kinds of boards... We just became obsessed with skateboarding.”

MacKaye and Garfield and their skater friends started their own skating team, Team Sahara (which MacKaye explained was a “corny joke” on how hot DC got during the summers, and how ‘hot’ they were as skaters), and began skating around the affluent DC suburb of Georgetown, building their own skate park from the wreckage of an abandoned police station. “We loved skating and we loved building ramps,” adds MacKaye. “At night we’d be like, ‘We need to procure some wood.’ We’d hit a construction site and get some wood and at 3AM, we’d have four people carrying sheets of plywood on their skateboards, hustling down the street. It became central to our existence. We’d check certain pools everyday to see if they were empty. One day we walked and skated something like 10 miles to the Pentagon to skate this V-shaped wall above this highway. It was kind of sketchy, but cool to skate. But if you fell, your board dropped off 20 feet. Then, in ‘78, Henry and I decided to go to California. I was 16 and he was 17. We got on a bus and went across the country. We first got to Northern California and went to the Winchester skate park.”

Like MacKaye, Garfield quickly became enamoured with punk rock, with the local DC scene and with Bad Brains in particular. Henry fronted his own group, State Of Alert (aka SOA), who played a handful of shows on the DC scene, and released a 10-song EP, No Policy, on Dischord in March 1981. Along with three tracks recorded for 1982 Dischord label sampler Flex Your Head, No Policy makes up the meat of the SOA discography, a nine-minute blitz of muscular, revving hardcore that made up for a certain lack of imagination with their grinding, uncompromising attack. Their songs followed the circular dervishes of Minor Threat hardcore, the minimal riffs chasing the haywire rhythm section, though guitarist Michael Hampton’s tone was bark-like and grating, a distorted buzz of a blackly Ginn-esque hue.

Their lyrics, penned by Garfield, were blunt and confrontational: song titles like ‘I Hate The Kids’, ‘Warzone’, ‘Riot’ and ‘We Gotta Fight’ suggest the cynicism and disaffection that fuelled them. ‘Public Defender’, meanwhile, played out like SOA’s own ‘Police Story’. “You see a cop coming, You better look quick, He’s gonna hit you with a stick,” barked Garfield, with an agitated bark like he was choking back tear gas. The chorus, droned over a piledriver guitar blitz, ran like a playground chant for the punker mosh pit: “Man in blue, he’s coming for you / Sirens red, you’re gonna be dead”.

Garfield had accompanied Teen Idles on a mini-tour of California, undertaken in the summer of 1980, which began with a three-day trip by Greyhound bus to the West Coast. The trip would prove educational for the DC punks: Jeff Nelson ran afoul of the LAPD after mooning some cops who’d been staring at his punk attire, a rebellious gesture that landed him, momentarily, in police custody. On a more positive note, the contingent of HBs who turned up to see the Idles’ LA show recognised the DC group as kindreds, and firm bonds were forged between both parties. The HBs followed Teen Idles up north to San Francisco, where they’d been scheduled to support The Circle Jerks, Flipper and The Dead Kennedys, only to discover club owner Dirk Dirksen had dropped them from the bill. Meeting skater Tony Alva at the headquarters of video fanzine Target Video later that night, however, made the trip worthwhile for the DC punks.

MacKaye drew much inspiration from the Idles’ brief Californian sojourn, and from the kid-run DIY scene the HBs operated within; the Orange County kids enjoyed a freedom, even under the watch of the LAPD, which MacKaye hungered for in Washington DC. “It’s a great city to live in, if you’re in your thirties or forties,” he told me, in 2002. “But it’s kind of a nightmare if you’re a teenager; you just fall between the cracks. If you want something to do, you’d better do something off your own back. One lesson I learnt was, if you live in Washington, don’t ever ask for permission, because the answer will always be ‘no’. Go about things on your own, and do it under the radar.”

In DC, Teen Idles had struggled to put on shows; too young to play at bars, they’d been stuck booking shows at community centres, and similar venues. In San Francisco, however, they’d seen All-Ages shows put on by hardcore kids at bars that allowed entry to teenagers as long as they had ‘X’s stamped on their hands, to indicate they weren’t to be served alcohol. It was a method they would soon put into practice at Teen Idles and Minor Threat shows to come.

The DC contingent’s trip out west did not, sadly, coincide with any Black Flag shows. MacKaye and Garfield had first discovered the group when their friend Mitch Parker gave them a copy of the Nervous Breakdown EP, which the pair soon played until they’d worn the grooves flat. “It was heavy,” remembered Henry, later. “The record’s cover said it all: a man baring his fists, with his back to a wall. In front of him, another man fending him off with a chair. I felt like the guy with his fists up every day of my life.”118 Revering them through their vinyl from afar, Ian and Henry didn’t get to catch Black Flag in the flesh until the Creepy Crawl visited the East Coast, early in the spring of 1981.

It’s a measure of the DC kids’ considerable love for Black Flag that they were willing to travel over to New York to catch the group at the Peppermint Lounge on March 14. The Washington kids felt great enmity towards the Big Apple, which they infamously gave voice to later that year during to a trip to New York to catch the taping of the Hallowe’en episode of comedy show Saturday Night Live, which had been cajoled by former cast member (and punk fan) John Belushi, returning to host that evening, to book Fear as musical guests. The resulting performance was so calamitous that producer Lorne Michaels kept the show out of rerun syndication for years after, as Fear rocked three brat-rock spats (including a scathing ‘New York’s Alright If You Like Saxophones’), assailed on all sides by skinheaded, leather-jacketed punkers. Before the director made a panicked cut from the violent melee to the ad break, MacKaye managed to snag singer Lee Ving’s microphone, howling “New York sucks!” at the top of his lungs.

Black Flag’s Peppermint Lounge show in March was trailed by another Manson-themed poster, this time depicting three young female members of Charlie’s family, cavorting naked with each other, one holding a screaming baby boy to her puckered lips, another carving an ‘X’ into their third’s forehead with a razor blade. Manson slogans, painted in blood, decorated the walls: “God is Now”, “Wash this out of your life”, “Twist and Shout”, while Raymond had scrawled “A kiss and a fix aren’t enough any more” along the image’s right edge. Beside the bars, at the head of the poster, ran text depicting the imagined discourse between the girls, declaring their fealty to Charlie, their love for him and faith in him. “Let’s say he gets out in 25 years, I can wait that long,” says one. “Let’s see, he’s twenty years older than me,” adds another. “In 25 years, he’ll be 60, and I’ll be 40...”

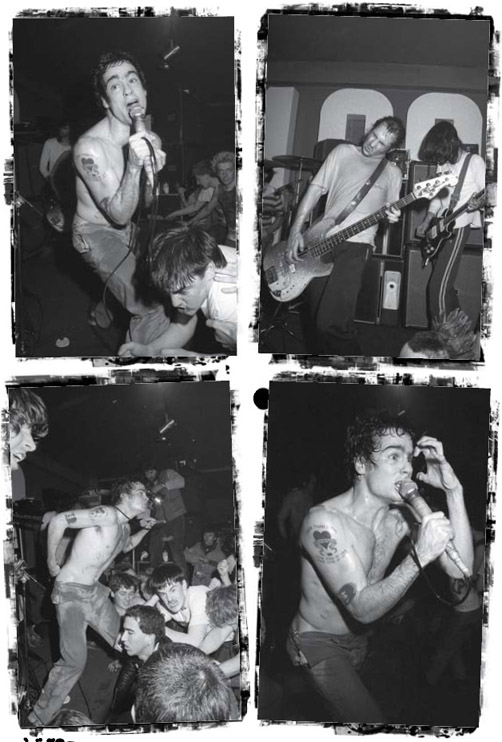

“The club was packed,” remembers MacKaye later, writing for Glen E. Freidman’s 1982 photo-zine, My Rules. He’d come to the show with a group of DC punk kids, including, of course, Garfield. “We sat content in the fact that we were finally going to see them. They were so important to us, almost living legends. They represented that total release, that personal rebellion we all felt so strongly. We had driven 250 miles to a city that we loathed, waited in lines to all hours of the night... We were laughed at, ridiculed for our social etiquette; we were definitely uncool... So we stuck together, tight. We sat in a small room, one eye on the videos, the other on the door, just waiting for shit... It must have been 2am when [Black Flag] finally came on. All 14 of us gathered at the front of the stage. There were eyes looking down at us, and sideways comments whispered all around us. But all that shit stopped as the first song started...”119

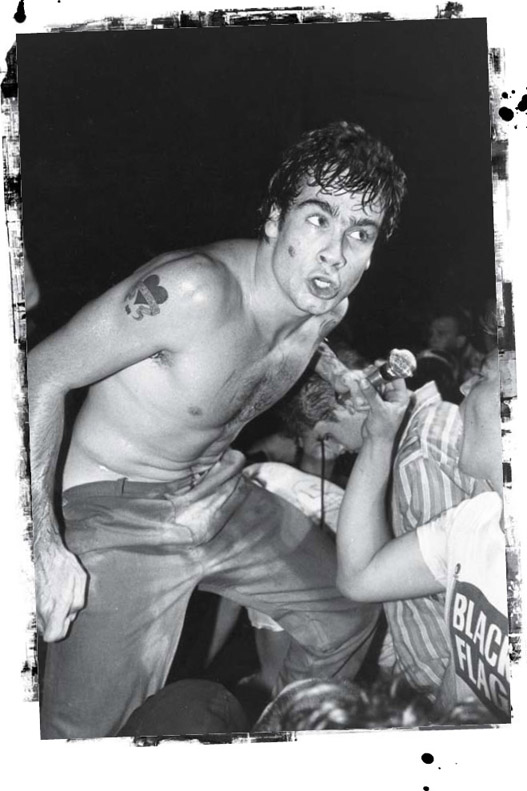

“The audience up front, mainly consisting of DC and Baltimore people, were hyped up and ready to thrash,” wrote Critical List zine’s correspondent. “The crowd was really dancing hard. Black Flag does a great job of getting their audience rowdy, mostly with Chuck’s steady banging & plucking on bass... They did a song, ‘Machine’, in which Dez screams repeatedly, ‘I’m not a machine’, and the audience joined in until they sounded like machines themselves. DC people were the rowdiest dancers, occasionally clambering on a stage over 5 ft. high & falling back into the crowd. Dez thanked DC punks for coming to the show. Most of the New York crowd, minus a select few, were pretty lame. By the end of the show everyone there knew people were up there from DC and most felt intimidated.”120

“All the songs were abrupt and crushing,” remembered Henry, of the Flag’s “short bursts of unbelievable intensity. It was like they were trying to break themselves into pieces with the music. It was one of the most powerful things I’ve ever seen... Made me wonder what planet they came from. I wanted to move there immediately.”

“We were a little scared,” MacKaye continued, “but hell-bent on doing what we had set out to do. Tensions ran high, but we ran higher. The atmosphere was hard, but we were harder. And when it was over, we had the last laugh. The city was still there, and we still hated it. But at least we had beaten it, we had caught it while it was sleeping (which wasn’t too hard), and it would remember. And it did.”

The Creepy Crawl continued on, visiting Pittsburgh rock club Decade on Monday March 16, and arriving at the 9:30 Club - a DC venue that would soon win a legend for supporting the local punk scene - on the Tuesday, where Black Flag were supported by Minor Threat. In anticipation of a wilder crowd than usual, for this potentially devastating one-two punch from the two figureheads of the new hardcore scene, the venue hired three extra security guards for the night. And sure enough, it was all hands on deck from the get-go, as the collision of HB brawn and Georgetown sass made for much (mostly) good-natured ‘controlled violence’ on the dance floor, although the club owners halted the show a number of times when the mosh pit’s chaos theory pell-mell seemed to reach critical mass.

Later that night, as was custom, Black Flag stayed over at MacKaye’s house, reaffirming the friendship between the two bands. And then Black Flag were off on the road again, back on the Creepy Crawl: to Boston, to Lansing and, finally, on Monday March 23, to Chicago, where they played with local punks Effigies and Naked Raygun at the Space Place. Advertised as “the triumphant return of the US’s hottest white soul band”, the show was followed by an after-party at punk club Oz, featuring a performance by a Minneapolis punk trio named Hüsker Dü, who greatly impressed the visiting Flag.

The extended trip, while wearing on Cadena’s vocal chords, and barely accruing enough money to pay for the tour, was still an impressive success, spreading the word of Black Flag across the country; if some shows were under-attended, they were still performed with the full-blooded vigour of a packed-out Flag show, in the knowledge that all who thrilled to the chaos and the noise would come again next time, with friends in tow. For sure, the Flag had made a deep impression on all the budding punk-rock communities they’d visited, and perhaps sown the seeds for further scenes where there hadn’t already been any. And yet, perhaps the most important relationship forged on the Creepy Crawl - that with the Washington DC scene - would in the long run end up making a deeper impression on Black Flag than vice versa.

Certainly, Henry Garfield felt the Flag’s impact, as the group’s rickety tour van left MacKaye’s driveway following the 9:30 Club after-party, off to continue the Creepy Crawl. The sheer excitement of the lives Black Flag had chosen to live - regardless of the sacrifices and struggle that accompanied it - threw Garfield’s own day-to-day existence into sharp relief: working 10 hour shifts as manager of the local Häagen-Dazs ice-cream store, and fronting a group who, while they made an impressive racket, would never change lives the way Black Flag were doing, on a nightly basis.

“I had a low-level panic attack,” he wrote. “I got a glimpse of something that made it impossible to bullshit myself... After I had hung out with the Flag guys, I saw that there was a lot more out there to be seen and done, and I didn’t think I was ever going to do any of it.”

While the mainstream press had, until now, covered Black Flag only as an excuse to exhale, disapprovingly, at the misbehaviour of hoodlum youths, Los Angeles Times rock critic Robert Hilburn wrote up an even-handed and often-admiring interview with the group for the June 16 edition of the paper. Headlined “Music For Inspiration”, and running with a Glen E. Friedman portrait of Dez, Chuck and Greg in the cramped offices of their latest digs in Torrance, the piece offered a potted history of the Flag story thus far; Greg and Chuck repeated the answers they’d already given countless ‘zines, with regard to the violence at their gigs, although Ginn’s reasoning on not wanting to exclude the rowdier element of their fans from their shows also included a dig at the Masque-era Hollywood punks he felt had ignored the group.

“We’re totally against anybody being excluded from shows or abused in any way because they might be uncool or because they might dress in a certain way,” offered Greg, although clearly it wasn’t the hipness of the audience’s attire that was in question, but rather their behaviour. “We know what it’s like to be included,” Greg continued. “We were shut out of the club scene here for a long time. For the first two years, we had to play in our garage because we couldn’t get booked at the Masque. They said it wasn’t cool to live in Hermosa Beach. We finally started putting on our own shows.”121 (Brendan Mullen today refers to the interview as “Greg’s blatantly disingenuous ‘rejected-by-the-Hollywood-punkscene’ spiel”, adding that it stung to read it at the time.)

In his interview with Hilburn, Ginn strove to present the community surrounding Black Flag as a caring one, with a depth of understanding for its young audience that perhaps eluded their parents. “Many people we hear from are real young,” he explained, “just 11 or 12. A lot of them can’t even go to the gigs, but they tell us about what happens to them. They look and dress a little different from the average person at school, and get lots of abuse for it. That’s what causes the reactionary thing at the shows, to the extent that it exists.”

The feature ran in advance of what would be the Flag’s biggest show to date in their hometown, at the 3,500-capacity Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, on Friday June 19, in the company of Orange County punks The Adolescents, the Flag’s Vancouver brethren DOA, and their San Pedro cousins The Minutemen. “The Minutemen opened to an angry skinhead crowd that were flipping them off and spitting on them and telling them to get off the stage,” remembers Dave Markey, in the audience that night. “I really liked them, though I seemed to be one of the few that did.”122

Seventeen-year-old Markey was a true believer in hardcore and punk, though he was certainly no HB thug; that year, he’d formed his own punk group, Sin 34, and a fanzine, We Got Power, with his friend Jordan Schwartz. He’d find perhaps his best means of expression, however, using his father’s old 8mm Brownie movie camera to make short films, and capture the punk shows he was seeing, later collecting much of this early footage as The Slog Movie, a vital document of the early hardcore scene.

Markey was living in Santa Monica at the time of the Civic concert. “I’d just graduated from Santa Monica High, which was right up the street from the venue,” remembers Markey. “At the time, I was a typical Southern Californian punk. I was the only kid in my graduating class who refused to go through the graduation ceremony, because I thought it was stupid: I wasn’t putting on a cap and gown, walking down the plank in front of everyone and getting a diploma. I just refused to do it. It seemed to me that my reward for graduation was the Black Flag show across the street, more so than going through with that stupid ceremony. And that set up the way my life has played out, that decision I made at 16... It’s pretty profound, it sends chills down my spine when I think about it now. Because it made total sense to me at the time, and it still makes sense to me now.”

The Santa Monica Civic show would be Markey’s first live experience of Black Flag. “The first LA punk band I saw was X, a year earlier, also at the Civic. We were kids, we didn’t drive, we didn’t go to Hollywood. We were down there in Santa Monica, which is a great place to grow up, a beach community. It’s a pretty big city, bigger than Hermosa Beach - less suburban, more city-like. But all the hardcore stuff came from these beach communities, a reaction to the lifestyles being foisted on us at the time. There was violence and fighting all the time, the longhairs versus the punks. It’s the same story as in Quadrophenia, the same story going on with the Emo Riots in Mexico City right now. Same story! Tribes fighting, that teenage thing.

“Punk really seemed to be one of the few things that was going against the grain, saying, ‘No, it’s time for a change.’ It seemed to be really important, for culture, art and music. Of course, I wasn’t thinking all that as a teenager - I was drawn to the music, because I really related to it. It was really empowering. And it seemed like I was making a stand. I was drawing a line in the sand, and that seemed really important. As the mainstream culture got more stupid, as the Republicans and the Christian Right started coming to power, you knew it was all wrong. The music helped make things seem better, it offered an alternative to the church, and the state, your parents... There was a heaviness to Black Flag. It wasn’t like just going out and buying a pop record; you wanted to go out and steal a Black Flag record... It seemed like a whole new world was opening up, and there was so much music happening at the time.”

Of the show itself, Markey’s most vivid memories are of Dez Cadena. “Dez was someone that I totally idolised, being a 17-year-old kid. Dez was the one in the band I became closest to, and we eventually developed a lifelong friendship. But I can remember being a kid, going to that show, and it was really all about Dez, it really was... He still sounds, to me, the angriest of all the singers, just in his growl, the way he sang.”

Also in the audience at the Santa Monica Civic were the members of Austin’s The Big Boys, visiting Los Angeles while en route to a show in San Francisco. “It was a big deal for Black Flag, because it was the largest show they’d ever played,” says Tim Kerr. “And it was a big deal for us, because it was the first time we’d seen so many kids at a show. Up until then, it had mainly been art students and college people who were at our shows in Texas, and there weren’t any kids. I mean, kids couldn’t come to shows, nobody was doing All-Ages shows yet.

“But when we saw the Santa Monica Civic show, and all these kids in the audience, it was like a lightbulb went off in our heads - this is what we need to do when we get back home, because these kids are the ones who are gonna keep this going. Those older people aren’t gonna keep starting bands, its going to be these kids. So when we got back home, we started flyering the high schools, and Chris’s little brother Nathan was just out of high school, so he spread the word. And we started looking for places that weren’t clubs that we could play shows at... It was a big thing for us. Punk rock, before hardcore, had welcomed newcomers to the table, but they weren’t actively recruiting people. Whereas Black Flag, they were bringing new kids into the scene, trying to keep stuff going. It was a big, positive movement, or at least it started like that.”

The Santa Monica Civic show also educated the Austinites in the ways of the LAPD. “The show was over, and we went outside,” remembers Kerr, “and I remember distinctly seeing a bunch of kids go running in one direction, and then some kids running in the opposite direction, and suddenly all these police appearing, with their batons swinging. And I was standing there like it was something off of TV. A friend grabbed me, saying, ‘C’mon Tim, this isn’t television, let’s go!’”

Police brutality had never really been a problem punk-rockers had to face in Austin, although The Big Boys had unintentionally gotten Raul’s shut down temporarily, after a gig frontman Randy had advertised with a poster using a nude model from gay porn magazine Colt led cops to believe the venue was hosting live sex shows. Nearby Houston was another matter, however.

“We played a show in Houston with The Dicks and MDC at the Island, and the Houston police showed up,” Kerr remembers, “and they were just as bad, if not worse, than the LA cops. They came with riot sticks. We were on last, everyone else had played and we were on stage, and we hadn’t started yet; I was messing about with my guitar, and Chris was fiddling with his bass. Next thing I know, I’m surrounded by three cops, and I look up and see Chris is surrounded by cops too. There’s a little fireplug of a cop, with a nightstick and a flashlight, right in my face, saying, ‘Stop playing’. He said he was shutting down the show. And stupidly, I said, ‘Why?’ And the guy gets on me, nose-to-nose, and barks, ‘Because I said so’. Just waiting for me to say, ‘Fuck you!’ or something.

“But instead, I said, ‘OK, fine’. They pushed all the people out onto the street, and I’m not sure if they got arrested. And they made the bands go back into the room backstage, which wasn’t really any kind of dressing room, and the MDC guys were yelling, ‘Police state! Police state!’ And Chris [Gates, Big Boys’ bassist] grabbed Dave Dictor by the neck of his shirt, so his feet were dangling, and said, ‘I don’t want to go to a Houston jail, so shut the fuck up!’”

Days after the Santa Monica Civic show, Black Flag set off on tour again, following an itinerary that swung through the East Coast and the Midwest, including a return to New York, this time playing 1,200-capacity ballroom the Irving Plaza, in the company of Bad Brains and UXA.

Every morning following the 9:30 Club show, Henry Garfield would play a demo tape of unreleased Flag tunes, given to him by Chuck, as he prepared for his day’s work at the ice-cream store. “I loved it because the tunes were great and the words said what I was feeling,” Henry wrote later. “I hated it, because I wanted to be the singer.” Garfield arrived in New York, for the Irving Plaza show, early enough to spend the afternoon hanging out and bonding more with the Flag. The show itself was a blast, and a second, after-show set, at a tiny club up the street called 7A, even better. But, as late night morphed into early morning, and Garfield stared at a five-hour drive back to DC, where he was to open the Häagen-Dazs in six hours, he realised he couldn’t stay any longer. So Henry scrambled on stage and asked the group to play ‘Clocked-In’, Ginn’s anthem for the frustrated wage slave, the words to which Garfield felt so keenly that night.

“This is called ‘Clocked-In’,” yelled Dez, to the crowd. “It’s for Hank, because he’s got to go to work now.” At this, the group unleashed the song’s hectic, heavy slalom riff, and Henry, unconsciously, clambered onstage, took the mic, and began to bellow the lyrics, as Dez good-naturedly stepped away, to give Garfield space to sing, and perhaps glad of the rest from the microphone, after another two-set night of howling.

In a photograph taken that night123, Garfield is stood onstage, dressed down in black slacks and a white, sleeveless tee-shirt, the muscles in his arms taut as he grips the microphone. His mouth is caught mid-bellow, a roaring, agape maw, but your gaze is drawn to Henry’s eyes, or rather the paper-cut slits where his eyes - screwed up in intense concentration - used to be, his brow dented in the middle with earnest furrowing. He looks intense, like he’s trying to force out a lifetime of repressed primal screams in one rushing exhale. He looks, undeniably, like a Black Flag frontman.

The memory of the night crackled within Garfield, and kept him awake, as he drove back to DC, to another 10-hour shift on no sleep. Black Flag, meanwhile, idled a little while in New York City, enjoying a rare gasp of downtime. This pause in their hectic schedule gave Greg and Chuck a moment’s peace to consider how to handle Dez’s fatigued vocal chords, which were still struggling to withstand the dual rigours of Black Flag’s heavy touring schedule. They liked Dez, both as a friend and as a bandmate, and they wanted him to stay on with the group. But their vision of Black Flag, and their ambitions for their music - the horizons of which only expanded as they continued along their Creepy Crawl - would demand much from whoever was singing with the group.

Their workload was only going to multiply as the band continued on, and the grind of their expedition was unlikely to let up soon, if ever. There was also their oft-postponed debut album to consider; the Flag had cut a number of further sessions at Media Arts with Spot during the early months of 1981, getting Greg’s newer songs down on tape, with an eye for release as a full-length. But there was little point in compiling and releasing such an album if Dez’s vocals wouldn’t be up to the tour schedule that would follow, to promote their first LP and build on the following they already had. Similarly, they couldn’t procrastinate for much longer; EPs might’ve been the ideal format for hardcore’s brief, ballistic bulletins, but the Greg Ginn songbook (with contributions from Dukowski, and other members of the Flag family) was maturing at speed; it was time for Black Flag to make the kind of self-defining statement for which a debut album was the ideal vehicle.

Greg and Chuck had already begun discussing introducing a new vocalist to Black Flag, and having Dez switch over to second guitar. Early candidates included their friend Dave Slut, frontman for New Orleans punks The Sluts; they’d even idly toyed with asking Ian MacKaye to sing for the Flag, although they ultimately decided that as ambitious, independent and already established a musician as MacKaye probably wouldn’t relish joining someone else’s band, and singing someone else’s songs. As Mugger later told James Parker, “They were looking for somebody young who they could kinda work on.”124

Henry Garfield’s performance of ‘Clocked In’ at the New York afterparty, however, had made a deep impression on the group, and suggested that the brawny DC brawler, another fan plucked from their baying mosh pit, would be the ideal choice. Time was only one of a number of luxuries denied Black Flag, so Greg and Chuck acted fast; they would propose the idea to Henry before moving on to the rest of the tour.

“We were in New York, enjoying some time off,” remembered Cadena, later. “I had bought a bottle, and was sitting on someone’s stoop in St Mark’s place, and I bumped into Chuck and Greg. They told me they were gonna ask Henry to be the singer. My voice was burning out - I wanted to play guitar in the band, and Greg and Chuck knew it. They told me they would buy me a guitar and amp. They liked his voice, but he was hesitant. He didn’t want to take my job and respected me, so they got me to call him.”

Cadena invited Garfield up to New York, to ‘jam’ with the band. After Dez rang off, Henry immediately called up Ian MacKaye, to share the news, and help him sift through his chat with Cadena, to see if an offer to join Black Flag was really lurking among the vague conversational debris. “I’m like, ‘Holy shit, am I being asked to audition for Black Flag?’” he remembered to Michael Azerrad. “What a huge, monstrous proposition to a barely 20-year-old guy with an extremely normal background.”125 He swiftly packed some gear together, and early the next morning made off to the train station, where he’d begin his trip to New York; he walked, rather than taking the cab, as he had plenty to think about during his journey, and the fresh air might clear his reeling mind.

Early the next morning, he met up with the Flag in Odessa, a restaurant in the East Village, where Greg explained that Dez was moving over to guitar, and asked Henry if he’d be up for trying out as a singer. With Garfield’s jaw still slightly agape in shock, they repaired to the nearby Mi Casa rehearsal studios, where the Flag set up their gear, and Henry found himself standing before his very favourite punk-rock group, microphone in hand, ready to grasp the opportunity he’d scarcely let himself dream about before this morning.

“Greg asked me what song I wanted to play first,” he later wrote. “I thought, I must be dreaming. For a second, I didn’t think I was there at all. I told him, ‘Police Story’. It was as if I’d flipped the switch on some angry machine. The entire band kind of reared back and lurched forward and I heard the classic Ginn feedback, and all of a sudden, we were into the song.” The group pummelled through every song in their repertoire, Henry impressing the Flag with his knowledge of their lyrics, and the way he’d fearlessly improvise words for the songs he’d never heard before. They were also impressed by the fact that he hadn’t flinched when, having exhausted their set list, they began to run through every song a second time.

At the session’s end, Chuck called a band meeting, and told Garfield to wait a couple of minutes while the Flag discussed the matter. Minutes later, he returned, and said, “OK.” OK what?, replied Henry. “OK, you want to join this band or what?”

Garfield returned home to DC that afternoon, with sheafs of Black Flag lyrics he was to commit to memory, before joining up with the tour in Detroit, in July. His first impulse was to call MacKaye, and seek his opinion on this unexpected bout of outrageous fortune. MacKaye, unsurprisingly, told his friend to grab hold of this opportunity with all his might, and not let go. Placing the telephone back in its cradle, Henry then set about putting his DC affairs in order, and planned his move to the West Coast. “It was great telling my boss I was quitting,” he later remembered. “He offered me more money, and I told him it wasn’t a money issue. He told me it was a crazy idea, and I should get back to work. He laid into me hard, and it got to me a little. Luckily for me, Ian was really behind me, and told me he knew this was going to be great and to go for it.”

The Crawl continued onwards, with a show at Pittsburgh’s colourfully named Electric Banana club, on Saturday July 4; a bootleg recorded at the show captures the magic of this era of Black Flag perfectly: a brutal see-saw between primal, life-affirming riffage (the great cleaving, anthemic chords of ‘Nervous Breakdown’ tearing through the air to raise a riot in the pit), and passages of potent and chaotic discord (the twisted squall of ‘Life Of Pain’ and ‘Room 13’, molten wreckages of noise that disturbingly evoked the tangled angst that brewed beneath the Flag’s righteous roundhousing). Dez Cadena’s voice holds out admirably throughout, but you can imagine the damage his splintered shrapnel roar must have inflicted on his throat, by the show’s messy end; like no Black Flag singer before him, Cadena heedlessly threw every iota of himself into the tumult of Greg’s songs, airing every bruise and scar, and allowing his wounds to bleed freely across the haywire caterwaul.

The following Friday, Black Flag’s tour van trundled into Philadelphia, where they were booked to headline the Starlite Ballroom. Support that night would come from State Of Alert, for what would be their last show, bidding adieu to their departing lead singer; the Georgetown posse made the commute to Pennsylvania for the momentous event. Garfield’s bandmates in SOA had initially been reluctant to play the show, harbouring some residual ill-feeling over their singer’s abandonment of the group; State Of Alert’s final set, however, served as a fine farewell to their brief gasp of hardcore glory, Garfield leaving the stage as their frontman one last time, before returning for Black Flag’s encore, an hour or so later, and officially fronting the Flag in public for the first time.

“Henry had been hanging out with those guys all night,” remembered SOA guitarist Mike Hampton, to James Parker, “but when he did ‘Police Story’ with them, it was weird: suddenly he was removed from us, he was one of the band.”126 The Flag’s set was combustive enough to stir a full-on confrontation between the Philly locals and the DC tourists, a fracas that spilled out into the street in front of the venue, and attracting the attention of the police, and more neighbourhood hoodlums. This subsequent pitched battle would reach ridiculous heights, involving an arsenal that included baseball bats and blackjacks and flick knives; the confrontation left three DC punks hospitalised in the aftermath.

Black Flag spent the weekend playing two nights in Boston, while Henry collected his things during one last trip back to DC, rejoining the group in Detroit on Tuesday July 14, where they were to play with The Necros at a bar named Bookies. For the rest of the tour, he would serve as Mugger’s mate, helping load gear in and out of venues, and working stage security. Dez would continue to sing, until they got back to California; acclimatising himself to his new duties as slowly as their schedule allowed, Garfield would sing the encores, and get a feel for Black Flag’s audiences.

The following night, Garfield received a vivid taste of the kind of combative atmosphere that would pervade Black Flag shows, as a gig at Chicago club Tut’s, supported by local hardcore greats The Effigies, went badly awry, thanks to overzealousness on the part of the venue’s bouncers. “A bouncer’s main purposes are to stop fighting, stop people from throwing stuff at the band, stop people from sneaking in,” wrote Chicago ‘zine The Coolest Retard, in their review of the show, “not to put some guy in a headlock for slamdancing - that’s completely stupid. During ‘White Minority’, the bouncers went nuts and started beating on the audience/dancers up front!”

As the show wore on, Chuck clocked one of the bouncers, who was beating up on a girl in the audience, with the tuning pegs of his bass; pouring blood, the bouncer was rushed to a nearby hospital, while the group raced through the rest of the set. Afterwards, as they loaded their gear into the van, they discovered that the venue owner had confiscated a number of Robo’s drums, and when Henry and Mugger went to retrieve them, they were threatened by the club’s bouncers, as the owner lectured them on what losers and fuck-ups Black Flag were.