IHAVE mentioned John Varley as one in the new circle to which Mr. Linnell introduced Blake. Under Varley’s roof, Linnell had lived for a year as pupil; with William Hunt, a since famous name, as a comrade.

John Varley, one of the founders of the New School of Water-Colour Painting, a landscape designer of much delicacy and grace, was otherwise a remarkable man, of very pronounced character and eccentricities; a professional Astrologer in the nineteenth century, among other things, and a sincere one; earnestly practising judicial Astrology as an Art, and taking his regular fees of those who consulted him. He was the author of more than one memorable nativity and prediction; memorable, that is, for having come true in the sequel. And strange stories are told on this head; such as that of Collins the artist, whose death came, to the day, as the stars had appointed. One man, to avoid his fate, lay in bed the whole day on which an accident had been foretold by Varley. Thinking himself safe by the evening, he came downstairs, stumbled over a coal-scuttle, sprained his ankle, and fulfilled the prediction. Scriven, the engraver, was wont to declare, that certain facts of a personal nature, which could be only known to himself, were nevertheless confided to his ear by Varley with every particular. Varley cast the nativities of James Ward, the famous animal-painter’s children. So many of his predictions came true, their father, a man of strong though peculiar religious opinions,—for he, too, was “a character,”—began to think the whole affair a sinful forestalling of God’s will, and destroyed the nativities. Varley was a genial, kind-hearted man; a disposition the grand dimensions of his person—which, when in a stooping posture, suggested to beholders the rear view of an elephant—well accorded with. Superstitious and credulous, he cultivated his own credulity, cherished a passion for the marvellous, and loved to have the evidence of his senses contradicted. Take an instance.—Strange, ghostly noises had been heard at a friend’s, to Varley’s huge satisfaction. But interest and delight were exchanged for utter chagrin and disappointment, when on calling one day, eager to learn how the mystery progressed, he was met by the unwelcome tidings: “Oh, we have discovered the cause—the cowl of the chimney!“

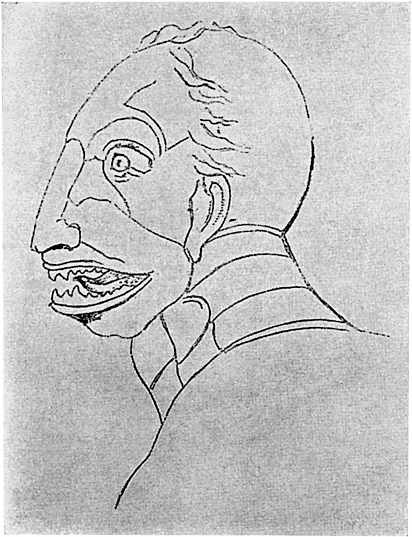

EDWARD I

WILLIAM WALLACE

EDWARD IIII, WHO NOW EXISTS IN THE OTHER WORLD

THE MAN WHO BUILT THE PYRAMIDS

To such a man, Blake’s habitual intercourse with the visionary world had special attractions. In his friend’s stories of spiritual appearances, sight of which Varley could never share, however wishful, he placed implicit and literal credence. A particularly close intimacy arose between the two; and, during the last nine years of Blake’s life, they became constant companions.

At Varley’s house, and under his own eye, were drawn those Visionary Heads, or Spiritual Portraits of remarkable characters, whereof all who have heard of Blake have heard something. Varley it was who encouraged Blake to take authentic sketches of certain among his most frequent spiritual visitants. The Visionary faculty was so much under control, that, at the wish of a friend, he could summon before his abstracted gaze any of the familiar forms and faces he was asked for. This was during the favourable and befitting hours of night; from nine or ten in the evening, until one or two, or perhaps three and four o’clock, in the morning; Varley sitting by, “sometimes slumbering, and sometimes waking.” Varley would say, “Draw me Moses,” or David; or would call for a likeness of Julius Caesar, or Cassibellaunus, or Edward the Third, or some other great historical personage. Blake would answer, “There he is!” and paper and pencil being at hand, he would begin drawing with the utmost alacrity and composure, looking up from time to time as though he had a real sitter before him; ingenuous Varley, meanwhile, straining wistful eyes into vacancy and seeing nothing, though he tried hard, and at first expected his faith and patience to be rewarded by a genuine apparition. A “vision “had a very different signification with Blake to that it had in literal Varley’s mind.

Sometimes Blake had to wait for the Vision’s appearance; sometimes it would come at call. At others, in the midst of his portrait, he would suddenly leave off, and, in his ordinary quiet tones and with the same matter-of-fact air another might say “It rains,” would remark, “I can’t go on,—it is gone! I must wait till it returns “; or “It has moved. The mouth is gone”; or, “he frowns; he is displeased with my portrait of him”: which seemed as if the Vision were looking over the artist’s shoulder as well as sitting vis-à-vis for his likeness. The devil himself would politely sit in a chair to Blake, and innocently disappear; which obliging conduct one would hardly have anticipated from the spirit of evil, with his well-known character for love of wanton mischief.

In sober daylight, criticisms were hazarded by the profane on the character or drawing of these or any of his visions. “Oh, it’s all right! “Blake would calmly reply; “it must be right: I saw it so.” It did not signify what you said; nothing could put him out: so assured was he that he, or rather his imagination, was right, and that what the latter revealed was implicitly to be relied on,—and this without any appearance of conceit or intrusiveness on his part. Yet critical friends would trace in all these heads the Blake mind and hand, his receipt for a face: every artist has his own, his favourite idea, from which he may depart in the proportions, but seldom substantially. John Varley, however, could not be persuaded to look at them from this merely rationalistic point of view.

LAIS OF CORINTH (CIRCA 1870)

Pencil

CORINNA THE THEBAN

Pencil

John Varley thus introduced Allan Cunningham to these drawings:—” This lovely creature is Corinna, who conquered in poetry in the same place (Olympia). That lady is Lais, the courtesan, with the impudence which is part of her profession, she stept in between Blake and Corinna, and he was obliged to paint her to get her away.”—”Lives of the British Painters,” by Allan Cunningham.

At these singular nocturnal sittings, Blake thus executed for Varley, in the latter’s presence, some forty or fifty slight pencil sketches, of small size, of historical, nay, fabulous and even typical personages, summoned from the vasty deep of time, and “seen in vision by Mr. Blake.” Varley, who accepted all Blake said of them, added in writing the names, and in a few instances the day and hour they were seen. Thus: “Wat Tyler, by Blake, from his spectre, as in the act of striking the tax-gatherer, drawn Oct. 30, 1819, I h. P.M.” On another we read: “The Man who built the Pyramids, Oct. 18, 1819, fifteen degrees of I, Cancer ascending!” Another sketch is indorsed as “Richard Cœur de Lion, drawn from his spectre. W. Blake fecit, Oct. 14, 1819, at quarter-past twelve, midnight” In fact, two are inscribed “Richard Cœur de Lion,” and each is different. Which looks as if Varley misconstrued the seer at times, or as if the spirits were lying spirits, assuming different forms at will. Such would doubtless have been De Foe’s reading, had he been gravely recording the fact.

Most of the other Visionary Heads bear date August, 1820. Nearly all subsequently fell into Mr. Linnell’s hands, and have remained there. Remarkable performances these slight pencil drawings are, intrinsically, as well as for the circumstances of their production: truly original and often sublime. All are marked by a decisive, portrait-like character, and are in fact evidently literal portraits of what Blake’s imaginative eye beheld. They are not seldom strikingly in unison with one’s notions of the characters of the men they purport to represent. Some are very fine, as the Bathsheba and the David. Of these two beauty is, of course, the special attribute. William Wallace and King Edward the First have much force, and even grandeur. A remarkable one is that of “King Edward the Third as he now exists in the other world, according to his appearance to Mr. Blake “; his skull enlarged in the semblance of a crown,—swelling into a crown in fact,—for type and punishment of earthly tyranny, I suppose. Remarkable too, are “The Assassin lying dead at the feet of Edward the First in the Holy Land” and the “Portrait of a Man who instructed Mr. Blake in Painting, in his Dreams.”

Among the heads which Blake drew was one of King Saul, who, as the artist related, appeared to him in armour, and wearing a helmet of peculiar form and construction, which he could not, owing to the position of the spectre, see to delineate satisfactorily. The portrait was therefore left unfinished, till some months after, when King Saul vouchsafed a second sitting, and enabled Blake to complete his helmet; which, with the armour, was pronounced, by those to whom the drawing was shown, sufficiently extraordinary.

The ideal embodiment of supernatural things (even things so wild and mystic as some of these) by such a man —a man of mind and sense as well as of mere fancy— could not but be worth attention. And truly they have a strange coherence and meaning of their own. This is especially exemplified in one which is the most curious of all these Visionary Heads, and which has also been the most talked of, viz. the Ghost of a Flea, or Personified Flea. Of it, John Varley, in that singular and now very scarce book, A Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy, published in 1828, gave the first and best account; one which Southey, connoisseur in singularities and scarce books, thought worth quoting in The Doctor:—

THE GHOST OF A FLEA

Fresco. (Tempera on panel)

PAINTED FOR JOHN VAKLEY, WHO, WHEN SHOWING HIS COLLECTION TO ALLAN CUNNINGHAM, DESCRIBED IT AS “THE GREATEST CURIOSITY OF ALL”

GHOST OF A FLEA

This spirit visited his (Blake’s) imagination in such a figure as he never anticipated in an insect. As I was anxious to make the most correct investigation in my power of the truth of these visions, on hearing of this spiritual apparition of a Flea, I asked him if he could draw for me the resemblance of what he saw. He instantly said, “I see him now before me.” I therefore gave him paper and a pencil, with which he drew the portrait of which a fac-simile is given in this number. I felt convinced, by his mode of proceeding, that he had a real image before him; for he left off, and began on another part of the paper to make a separate drawing of the mouth of the Flea, which the spirit having opened, he was prevented from proceeding with the first sketch till he had closed it. During the time occupied in completing the drawing, the Flea told him that all fleas were inhabited by the souls of such men as were by nature bloodthirsty to excess, and were therefore providentially confined to the size and form of insects; otherwise, were he himself, for instance, the size of a horse, he would depopulate a great portion of the country.

An engraved outline of the Ghost of a Flea was given in the Zodiacal Physiognomy, and also of one other Visionary Head—that of the Constellation Cancer. The engraving of The Flea has been repeated in the Art Journal for August, 1858, among the illustrations to a brief notice of Blake. The original pencil drawing is in Mr. Linnell’s possession. Coloured copies of three of the Visionary Heads— Wallace, Edward the First, and the Ghost of a Flea—were made for Varley, by Mr. Linnell.