BREATHING INTO PRACTICE

It had long since come to my attention that people of accomplishment rarely sat back and let things happen to them. They went out and happened to things.

—LEONARDO DA VINCI (source unknown)

What I love about this quote is not the “people of accomplishment” part, but rather the second sentence—“They went out and happened to things.” It’s not only his clever flip of language, but the very idea that we have to go out and happen that I find intriguing. This idea implies a sense of effort and self-initiation, a willingness to stick our necks out and practice, which is the focus of this section.

On the brink of completing my PhD, I spoke to a mentor of mine—a very well-published author—about building a writing career. He told me that every single year he reads at least one book on the art of writing. I have to say I was astonished. Here was a man in his seventies who could conduct workshop upon workshop on writing successfully, and he had the humility and commitment to continue to study writing as a craft. Every year. Continuously. Even after reaching the New York Times bestseller list.

In our pursuit of creativity, there are moments of spontaneous inspiration, moments when we feel possessed, when we know that all we need to do is open up and allow the words (or notes or movements or brushstrokes) to pour through us. But we all know, no matter how much we wish it so, that this is not our constant reality. Our creative endeavors also demand study, attention, and practice.

In deep creativity, practice is not only literal. Of course, if we are a writer, we need to practice writing; if we are a painter, we need to practice painting; if we are a musician, we need to practice music, and so on. This is the way we develop and get to know our art—what works for us and what doesn’t, what is our particular way of writing (or dancing or sculpting or playing or painting or photographing) that makes us unique. One main goal of practicing our art in the literal sense is to come to know ourselves—our strengths, our weaknesses, our idiosyncratic nature—through that practice.

But in deep creativity, breathing into this way of practice can have other meanings beyond the literal. Before we write our collection of poems, for example, we may need to practice noticing or attentiveness. Our practice may not be sitting down and writing a poem every day but taking a walk each morning and paying close attention to what small things grasp our heart and attention. Before we grab our camera and practice framing an image, we may need to practice visualization, meditation, or our inner focus and sense of things. The famous American photographer and environmentalist Ansel Adams once said in a video from the Getty Museum (now easily found on YouTube), “When you visualize a photograph, it is not only a matter of seeing it in the mind’s eye, but it’s also, and primarily, a matter of feeling it.” He adds that “the picture has to be there clearly and decisively, and if you have enough craft in your own work and in your practice, you can then make the photograph you desire.” Adams is not talking about his mastery of aperture or shutter speed but the practice of fine-tuning his mind’s eye, his visualization, his intuitive sensibility.

When we get stuck or go through periods of feeling dry and uninspired, our practice may not be to pick up the guitar and pluck away at the strings endlessly until something within us comes alive again. That may work eventually, but our practice in these moments could also be to pause, grab a journal, and begin to write out a dialogue with Stuckness—asking this visitor why it has come and what it has to say.

A close friend of mine was a professional ballet dancer. She told me that, for one year, her practice was to watch, either in nature or on video, the way different animals move their bodies. Of course, she was still in the studio every day literally practicing her pirouettes and arabesques, but the few minutes she spent every day observing the magnificent beauty of various creatures in their natural habitat inspired her immensely.

As we breathe into this section on practice, you might take a few minutes to reflect on one practice that you can adopt, be it quite literal (such as a writer reading a book on the craft of writing) or slightly tangential (such as a dancer watching animals move their bodies), which may help to spark or inspire your creativity. The power, as with any practice, lies in repetition and dedication, in allowing ourselves to deepen into the experience and know that there are layers upon layers to be discovered in one simple thing, should we give ourselves wholeheartedly to it. It will demand persistence and self-initiation, but perhaps this is exactly how we go out and happen to things.

The Creative Practices: An Imaginal Dialogue with the Voice That Moves (and Blocks) Me

Deborah

We hardly knew one another, but we sat in a circle and spoke about the marginalization of the muse—how or if we had allowed convention to overcome internal creativity. Had the depth of our creativity been stifled? Is this something we allow or are conditions in our modern time set up to ensure this?

A middle-aged gentleman, stick thin with a sunken face and sad eyes, spoke about how he had decided to attend this workshop (“Music and the Internal World,” offered by Dr. Allen Bishop) to find assistance with his “lifelong struggle with music.” He began by speaking of his childhood. For years, he watched, in awe, his father play any instrument that was placed before him with ease and precision. Then he told his own story—how he began playing guitar at a young age, joking that he knew it would be the only way for an awkward, skinny guy to get girls. He hardly laughed at his own joke, just a whimper of a muffled chuckle.

But, finally, a dim light emerged behind his eyes when he spoke of how playing music gave him unmeasured joy and expansion, how he would feel more alive and more himself when he was strumming his guitar than any other experience in his life. For hours, he would leave this world of time and get lost in his art, transported to an entirely new existence. But he hadn’t played in years.

He stammered to admit that two guitars sit next to an empty keyboard in a room in his house that he walks through multiple times every day. He cannot bear to see the instruments there, collecting dust, not producing any sound, but he glances at their haunting presence each time he passes by. He wonders, desperately, why he doesn’t play anymore. Sensing his sullen mood, the instructor asked him gently if perhaps it had something to do with the sorrow or pain that music often opens within an artist. Tears gathered in his swollen eyes and after a long pause, he responded, in a low tone, “I think it has more to do with the joy.”

With these simple words, it was as if someone struck a chord within me. The vibration resonated in some far corner of my heart, filling my entire body with an ache—not of pain but of being stretched, like a ravine being deepened. I thought of my own writing. I often feel transported to a numinous experience where returning both from the moment and to the moment feels like traversing a thousand miles into and away from the world. It is often painful in any attempt at recalibration. For many years, I have felt that writing is both my invitation into this life and my exile from it. I knew that joy that he spoke of. The joy that holds both ecstasy and agony. The joy that cracks me open to a field of emotional experience that is difficult (and painful) to return from.

JOY AND SORROW, PERSONIFIED

I closed my eyes and let his words echo throughout my body: “I think it has more to do with the joy.” Each time, repeated, the words struck a deeper chord. Until suddenly, I had an imaginative vision of Joy as a lavishly beautiful woman, with red hair and olive skin. She held a golden axe in her left palm and the hand of another woman in her right. The other woman was just as alluring and seductive but darker in complexion and color. I knew it was a personification of Sorrow—Joy’s inevitable companion. In her other hand, Sorrow held a cloth—as if Joy breaks us open and Sorrow enters in to wipe us clear. This vision helped me to realize that they always appear together—as a pair of opposites, each holding the potential and space for the other. I felt called to know and understand them more deeply. Not as my emotions but as these beautiful women who appeared to me.

In depth psychology, James Hillman wrote about a phenomenon called “personifying.” In his revolutionary work Re-Visioning Psychology, he defined it as “imagining things in a personal form so that we can find access to them with our hearts.” In other words, we allow an emotion or feeling or experience to become alive and embodied. When we do, a figure (or personification) appears, and we now have someone to relate to. Someone to speak to. Someone to understand and get to know.

A light and contemporary example of this can be found in the animated Pixar movie Inside Out. In this movie, various emotions (Joy, Fear, Anger, Disgust, and Sadness) are embodied characters that live within the psyche of a young girl named Riley. Each has their own personality, their own voice and perspective that influence Riley in different ways. Throughout the movie, we come to know, be amused by, and love them all.

Personifying can become a powerful and enlightening practice in our creative lives. With personifying, we discover the forms or figures within an event or experience. This opens and allows a new way of relating to the world within and around us. In fact, Hillman went so far as to claim that it “offers [us] another avenue of loving.”

To understand personifying more explicitly, it’s useful to explore actual examples. Personifying often happens quite spontaneously to us as artists, but becoming aware of when it happens and spending additional time with the figures that appear can truly enliven our creative spirit and work.

Personifying may happen when we sit down to write a poem about the beautiful new trees budding after winter, and Spring appears to us as a figure, with particular attributes, to be related to. Personifying may happen when we light a fire and see the flames as dancing angels of light, then allow ourselves to follow their movement in physical expression. Personifying may happen when we take up a paintbrush after meditating on a goddess and allow her to guide our hand in the creation of what comes before us on the canvas. Personifying happens when on a walk in the park, we are suddenly struck by the wonder and beauty of an old tree, hear its voice, pause, and listen to what it has to say. While lying on the grass, we may hear a heartbeat and spontaneously imagine ourselves within the arms of a great, warm, all-embracing Mother. Personifying happens when we close our eyes and look at a fear looming inside of us, and we see the fear come toward us as a lion. In all of these examples, there is an independent form within an event, phenomenon, or object that opens a new potential for relatedness, imaginal understanding, and love. As artists, we can explore and get to know these figures and forms more intimately as a creative practice.

When I closed my eyes after the initial vision of Joy and Sorrow, I found myself focusing on the cloth in the hand of Sorrow. It was oddly beautiful. It reminded me that there was something healing, something connective, something inspiring, something inexplicably alluring about pain. I knew these two (Sorrow and Joy) were the companions along the artist’s path, both unquestionable and equal in their seduction.

This vision continued to live within me for days, even weeks, after the seminar. There was such sorrow in that man’s eyes when he spoke about the joy he experienced when playing his music, the strange dichotomy embodied in his sullen expression of ecstasy.

I couldn’t help but wonder how, as creatives and artists, we can become possessed by a complex force, one that both drives us forward (providing accelerating surges of inspiration) and holds us back (drying in an instant any moisture within our creative lives). It was as if a third figure appeared in my imagination that held both Joy and Sorrow within her grasp, and I longed to know more about her. She introduced herself as the Creative Impulse.

THE CREATIVE IMPULSE

Art stretches us beyond our normal or comfortable human capacity. After an intense period of creative inspiration, it can feel impossible to stuff the expanse of what we experience back into our bodies and go about living our conventional lives. We become stretched, yoked, pushed, and pulled by our impulse to create. This can feel like a possession, greatly awakening and yet demanding of the artist. In a lecture he delivered in 1922 on the relation of analytical psychology to poetry, C. G. Jung declared,

Analysis of artists consistently shows not only the strength of the creative impulse arising from the unconscious, but also its capricious and willful character. The biographies of great artists make it abundantly clear that the creative urge is often so imperious that it battens on their humanity and yokes everything to the service of the work….The creative urge lives and grows in him like a tree in the earth from which its draws it nourishment. We would do well, therefore, to think of the creative impulse as a living thing implanted in the human psyche.

As artists, what is this creative impulse that seizes us? What is this living thing implanted in the psyche? After a myriad of explanations flooded my conscious mind with concepts such as the muse, the daemon, the spirits, etc., I decided to let the creative impulse speak to me in an imaginal way.

Deep creativity is mysterious.

After all, our conceptions and interpretations fall miserably short of capturing what it is that moves us, and so, perhaps the way to approach the creative impulse is to allow her to speak for herself. (For me, it appeared as a female figure. For you it may be different.) It was Einstein who stated that “imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

I sat down, waited in silence for many minutes, and then asked the creative impulse to speak to me. The response came very quickly and in a poetic form:

Don’t bring me your lists.

I know nothing of convention,

of the shoulds and should nots

of conscious contemplation.

I come to you as the faintest whisper

riding on the swollen breeze

to kiss your ear

with intolerable intrigue.

Or as the hurricane

that appears instantly

to demolish the square structures

you have come to reside,

adequately, within.

I hold the seduction of sorrow

that dwells in the mortal experience

and I know of your longing.

I inhabit your senses

and transport you to a world

where you are both

fully divine

and fully human.

I overtake your body

so you will finally pay attention

to the wondrous wisdom

that resides there.

I seize your emotions

and turn them into marvelous companions

that only your heart can bear.

I am the boat

that carries you away from dry, parched shores

along sparkling waters

to a realm of imaginal knowing

that only recognizes you

as a representative

of the many wise and crazy ones you carry inside.

Yes, you may avoid me

but at some point

your creative survival

will depend upon following my lead

and giving yourself entirely

to my striking

and possessive impulse.

I dropped my pen. And read that poem over and over and over again. As a creative practice, I believe we are called, as artists, to forge a relationship to the creative impulse within us—the living thing implanted in our psyche. It’s not always an easy process, but personifying allows us to do this more easily. When we allow the creative impulse a voice, an essential form, we have someone to understand, get to know, and relate to.

As we form an ongoing relationship with this impulse, we begin to develop a deeper understanding of our own creative process—how she appears, how she moves, what she wants, how to work with her. This relationship is an essential and sacred one. When we observe her patterns, we are gaining the keys to unlocking our creative potential. And since we inhabit a different psyche, the creative impulse within me appears, grasps, inspires, and demands something distinct from the creative impulse within you. The essential point is beginning the relationship—coming to know and understand her, so that we can work more consciously with her brilliance, stubbornness, fickleness, trickiness, and shifting tides of inspiration.

Deep creativity is receptive.

I felt compelled (as a creative practice) to engage with the voice of each verse in the poem I shared above. This allowed for a deeper revelation and dialogue, which I think is a useful example for this essay on creative practices, demonstrating a personified and enlightening dialogue, which you can also emulate in your own unique way.

In the dialogue to follow, I represents my voice, and CI represents the voice of the Creative Impulse:

Don’t bring me your lists

I know nothing of convention,

of the shoulds and should nots

of conscious contemplation.

I: What then do you know?

CI: I only know of the moon and her tides and what moves below the surface of things. I know what stirs in the depths and in the worlds invisible. The surface is of no interest to me.

The problem is there is too much “sense” in this world and not enough nonsense. Don’t you know that it is the combination of these two that leads to the supreme meaning?

If you are to be an artist, you must live among the madness of the masses and not give into it. You must defend and protect nonsense—run among the marketplaces and shout that you have found a great and rare treasure. When you believe it, people will believe you.

I come to you as the faintest whisper

riding on the swollen breeze

to kiss your ear

with intolerable intrigue.

I: I know this all too well. I have come to crave silence and solitude for I know they are pregnant with your voice. I listen for you. I know when you are calling. I am often frustrated with the loud and invading noises of distraction. I feel pulled away from what is real, from what I yearn for.

CI: Yes, the need for solitude is a peril of the artist. You know it well. If the winds within and around you are howling, you will not hear my whisper.

Or as the hurricane

that appears instantly

to demolish the square structures

you have come to reside,

adequately, within.

I: Why, if with a whisper you can produce a sound within me louder than a thousand horns, do you need to come as a hurricane? Are you not being reckless and destructive?

CI: Do you not know the thickness of the fibers inside your own ear? Do you not see the ropes around your ankles that still attach you to external approval? Convention and the spirit of the times can be sneaky. They will have you building white boxes before you know it, placing your inner belongings away neatly. There is a constant threat that I may lose you. That is why I must demolish what traps you. Have you ever tried working in a cluttered space? How am I to breathe and come to life and awaken your sleeping soul when I have to tiptoe around your inner clutter and trip over boxes? Sometimes, there must be a clearing out.

I: A painful one.

CI: Indeed, and pain is not something, as an artist, to run away from. It exists, like the stem of a flower. Without the stem, no petals are possible. Without the stem, the colorful flowers that the world enjoys would have no nourishment for growth.

I: Is there a trick to enduring this?

CI: When the hurricane comes, don’t push the wind. Lie down. Let the clearing happen. Trust that I am the place from where all creation comes. If I destroy, it is only for the sake of further creation. This you must not forget. Breathe this knowing into every morsel of your being.

I hold the seduction of sorrow

that dwells in the mortal experience

and I know of your longing.

I: The seduction of sorrow…can you explain this to me?

CI: Sorrow is the thread that weaves your single life into the collective life of humanity, that ties you to the ancient ones and will pull you forward, long after the disintegration of your body, into the experiences of humanity in the future.

Feelings do not come alone. You can never possess just one. Intense feeling in one sense means loss of that feeling in another. Joy contains sorrow and sorrow contains joy. You know this—you have seen them traveling hand in hand with a golden axe and a cloth, to create and soothe the wounds that all mortals share.

I know of your longing for holy connection, to be woven in to a larger scheme, to see what is not always visible but is always there, to write of the mysteries in a desperate attempt to touch upon them. Sorrow is the cup that holds the joy of oneness.

Secretly, we all long for this. Artists know this and don’t shy away. Great pieces of art, some of the best in history, emerge from an immersion in sorrow.

I inhabit your senses

and transport you to a world

where you are both

fully divine

and fully human.

I: I am beginning to feel tired, what do you mean?

CI: Have you not felt, when you give in to me that you come alive—that sounds, tastes, and sights are inexplicably sweeter and you understand, more intimately than ever before, what it means to create and be created? In these moments, you touch the hands of the gods and they touch you. You are not so distant—you and they—the creator and the created. You move out of and yet into your human beingness.

If you allow them, these moments will awaken an entirely new sensitivity—the most mundane of stimulus can inspire epics of creative work. Yes, you will be so utterly lost in the drunkenness of it all and simultaneously found—as if you had been searching for this your whole life and never really knew what you were looking for. But you will know. In these moments, you will know.

Deep creativity is participatory.

I overtake your body

so you will finally pay attention

to the wondrous wisdom

that resides there.

I: The body can be deceiving—is wisdom not a faculty of the mind?

CI: For too long you have cut yourself off from a great well of insight. Your body holds a pathway to revelation. It is a sacred container that holds and stores energy, experience, and impression. An artist, disconnected from her body, will find herself producing forms ungrounded, lacking the power and weight of embodied experience. An impulse or feeling in your body is the key to unleashing storms of psychic and creative energy. Don’t pass these by.

I: And if I do?

CI: I will ensure you do not.

I seize your emotions

and turn them into marvelous companions

that only your heart can bear.

I: Emotions as marvelous companions…? I see this but, sometimes, I wish to leave them sleeping on the side of the road while I hitchhike with less volatile company.

CI: What is it in you that searches for stability so incessantly? Would you wish to sleep each night without the company of dreams? Emotions, like characters in your dreams, exist to lead you into and away from yourself. The trick is not to bury them within the graveyard of your heart but also not to let the ghosts run free and possess you. You must harness them for their creative energy. If you look closely, I am within each one.

Your creativity, without emotions, is like a vein with no blood. If you kill your emotions, you kill me. I will contain them, as your veins contain your blood. You must know this so you don’t spend your life draining yourself of blood and then desperately seeking infusions from the thrill and rage of this world.

Deep creativity is emotional.

I am the boat

that carries you away from dry, parched shores

along sparkling waters

to a realm of imaginal knowing

that only recognizes you

as a representative

of the many wise and crazy ones you carry inside.

CI: When I come to meet you, I do not come to meet the “you” that meets the world. I come to meet the many voices, parts, and pieces of you, and I demand your entirety. Are you willing to give this to me? This means you must listen to each one and no longer pick and choose who you recognize within yourself and who you recognize within others. It demands courage and a plunge into dark and unknown waters.

I: This feels consuming. Why is so much being demanded of me?

CI: Do you not see what is riding on this? I am speaking of your creative life.

I: I do not have to listen to you.

Yes, you may avoid me

but at some point

your very survival

will depend upon following my lead

and giving yourself entirely

to my striking

and possessive impulse.

TENDING THE RELATIONSHIP

I had nothing else to say. I felt speechless. And yet, I had begun to relate to a great mystery that had been ruling my creative life for many years. This was the voice that moves and blocks me, and I felt an essential pull to know her more intimately.

Why had I not had this conversation before?

Perhaps, because I had never been introduced to the practice of personifying before. I had no form or figure to relate to. Once I did, however, a deep level of intimacy and understanding opened up for me.

After this exercise, I began to pay a lot more attention to when she showed up. And, often, it was not in the moments I wanted her to. I would sit down, light a candle, have a large chunk of time set aside for us to collaborate, and she would vanish. Nowhere to be found. Only to appear in moments when it was incomprehensibly inconvenient. Let’s just say we have a complex relationship. But what became immensely awakening for me, as a writer and creative, was the practice of honoring the creative impulse whenever and wherever she showed up. No matter what. I felt like she was testing me, figuring out how much I was willing to commit to the creative life, which I claimed to crave.

Deep creativity is receptive.

Through this practice, I began to realize that when the creative impulse appeared and I did not listen (or I intentionally ignored her), she would appear less and less…and less. Imagine if you kept visiting your friend, and she never let you in. Eventually, you would simply stop visiting.

When I did notice her, however, and made the conscious choice to let her in—no matter what obstacle was present at the time of her arrival—she kept appearing. I began to carry a tape recorder and small notebook to jot down inspirational ideas when they came at inconvenient times. The “notes” feature on my iPhone is full of her poetic fragments and creative musings.

I believe it is essential to our development as an artist to forge a relationship with our own creative impulse—to allow her (or him) a voice and to get to know her, as a personified figure implanted in our psyche.

This often demands a lot of care, time, and flexibility, but we can treat it as an ongoing practice, essential to our creative emergence. We are coming into an intimate relationship with a very sacred part of ourselves as artists. And like all great relationships, this one needs tending, care, attentiveness, and love to thrive and grow.

I wonder what your own creative impulse has been waiting to reveal to you. You will only know if you begin the dialogue and remember it is a holy conversation—ongoing, revelatory, and deeply mysterious—and perhaps, one that provides the map to unravel the complexity of your own creative life.

EXERCISES

Deborah invites you to these reflections.

Think of a time when you completely ignored your urge to create. What happened? How did you feel? What was the consequence? And also, what was the gift (what did you learn?) that showed up after your neglect?

Think of a time when you completely ignored your urge to create. What happened? How did you feel? What was the consequence? And also, what was the gift (what did you learn?) that showed up after your neglect?

Are you familiar with the practice of personifying? Have you ever tried it before? Are you moved to learn more about it or try it now?

Are you familiar with the practice of personifying? Have you ever tried it before? Are you moved to learn more about it or try it now?

In my dialogue with my creative impulse, I was told, “An impulse or feeling in your body is the key to unleashing storms of psychic and creative energy.” How does your creative impulse show up in your body? What emotions attend its arrival and its departure?

In my dialogue with my creative impulse, I was told, “An impulse or feeling in your body is the key to unleashing storms of psychic and creative energy.” How does your creative impulse show up in your body? What emotions attend its arrival and its departure?

Can you create something from these reflections?

Deborah invites you to this practice.

FORGING A RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR CREATIVE IMPULSE

I’m sure all artists feel like they have a relationship with their own creative impulse. I certainly thought I did. But what I came to discover is how much a practice like personifying can deepen the relationship, make it more conscious and more reciprocal. In my essay, I stated, “I believe it is essential to our development as an artist to forge a relationship with our own creative impulse—to allow her (or him) a voice and to get to know her, as a personified figure implanted in our psyche.” So whether or not you’ve tried personifying before, I invite you to try it now, with your own relationship to your creative impulse.

You might do just what I did. Sit in silence, quiet your mind, and invite Creative Impulse to speak to you (capitalizing it like that gives agency, as it becomes a “person” in its own right). She may speak to you in the form of a poem, like she did to me. Or he may ask that you draw an image or sculpt him into clay. She may ask to move through your body so you can feel what Creative Impulse feels when given physical expression. He may sing to you his story.

Sometimes in personifying, nothing comes. We don’t hear anything but our own mind’s chatter. We often know we are really personifying the other when we are surprised by what comes out of the practice, as I was rendered speechless after my dialogue with Creative Impulse. So if nothing comes to you in the silence, it’s okay to be more active. You may wish to take out paper and pen, or open your laptop, and after a period of silence, ask Creative Impulse a question. Write or type the question, and then “take dictation” of the answer you hear. Sometimes it’s easier to “hear” with our eyes closed (though it may be harder to read what we’ve written!). This is known as automatic writing, and if we stay with it without censoring what comes out through our hand or our fingertips, we may find we’ve accessed a wisdom we did not know we possessed—or rather, that is possessed by that personified figure implanted in our psyche.

Having these dialogues with Creative Impulse can be part of an ongoing practice of getting to know him or her. In fact, you may want to try this: every time you sit down to create, first invite Creative Impulse to speak to you and through you. This invitation for dialogue, this intention to forge a relationship, may really deepen what you then create together.

Strategies to Survive the Flood, Land the Plane, and Get the Kernel to Pop without Mortifying Oneself at 4:00 in the Morning

Jennifer

I’m staring at the blinking curser on the screen. Staring is not writing. My fingers are hovering over the keyboard. Hovering is not writing. I can’t write a word, except for writing about how I can’t write a word. Thirty-nine words so far. If I remove the contractions, forty-one.

Why has this been the only essay I haven’t looked forward to writing? Why have I put off writing it until the very last minute? Deborah’s and Dennis’s essays rest comfortably in my in-box, while I wrestle uncomfortably with mine. With even beginning mine.

Open with a confession, then. Write one true thing.

I feel like a fraud.

We’re supposed to be writing on our creative practices. I have none. I have no creative practices. I don’t even have a creative practice, singular, in the same way I have no meditation practice, though I would like both. I would love to wake up in the morning and say to myself, “Good morning! First, let’s practice meditation, and next, let’s practice creativity, and then go on the day’s merry way.”

I tried once. Dennis is my creative hero, so I thought I’d emulate him. It sounded so simple. Wake up early, enter my study, light a candle, and practice. I bought candles. I set my alarm. I slept through my alarm. I set my alarm again the next night. I woke up when it went off, but it was still dark, and it seemed ill-conceived to go to bed in the dark and wake up to the dark. I went back to sleep. The next night, I checked the time for sunrise, and set my alarm for then. When it went off, I squinted my eyes, saw the nascent sun between the slats of the blinds, and got up, only to realize I had no study to enter, only an office I shared with my partner. I crawled back in bed, put my arms around her, and silently blamed her for my lack of creative practice.

When we broke up and the office was mine again, I still didn’t get up to practice. I couldn’t blame her, and I wouldn’t blame myself, so I blamed Dennis for putting such an impossible practice in my head as some Platonic ideal. He’s not the only one—there’s a host of creative types who extol the ideal of discipline to one’s craft. Let Bernard Malamud represent them all with his words: “Discipline in an ideal for the self. If you have to discipline yourself to achieve art, you discipline yourself” (in Conversations with Bernard Malamud).

I am undisciplined and without a practice. And I still have those candles—unburned.

I joke about Dennis, but the serious truth is, the necessity for a creative practice has been clear to me for some time as a way of dealing with a phenomenon I often suffer from: creative flooding.

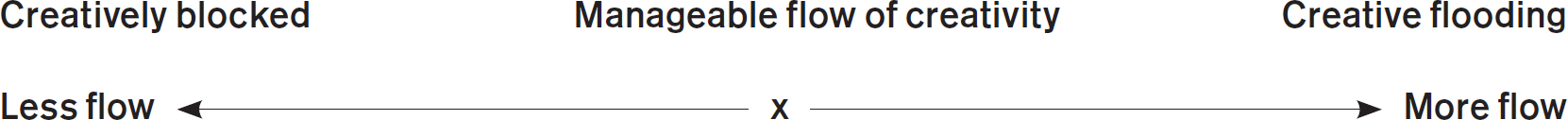

I borrow this term from a dissertation by the same name written by Emily Ann Meek. She describes creative flooding in this way: “Creative flooding can be defined when considered in relation to two already well-known terms that we use when discussing a person’s flow of creativity. These are ‘to be creatively blocked’ and ‘to have a manageable creative flow.’ When we say that an individual is ‘creatively blocked,’ we understand this to mean that his or her flow of creativity is, for some reason, inaccessible or cut off. No new creative ideas are coming into consciousness for this individual. On the other hand, another person might be experiencing a manageable, workable flow of creative ideas….Creative flooding refers to a further increase in the creative flow beyond the point where it is considered manageable. When this happens, the individual may experience this increased creative flow as excessive and overwhelming….At issue is the overwhelming too-muchness of what the individual has to deal with.”

She provides an illustration of this dynamic.

Meek notes that there are many books written on creative blocks, offering suggestions and techniques for getting the creative waters flowing again. It’s one of the questions frequently asked of creative people, writers especially. How do you deal with writer’s block? Ernest Hemingway, in a 1959 interview with the Paris Review, answered the question this way: “A writer can be compared to a well. There are as many kinds of wells as there are writers. The important thing is to have good water in the well, and it is better to take a regular amount out than to pump the well dry and wait for it to refill.” Great advice, right? Never let the well run dry. But what happens on the other end of the spectrum? What happens when there’s good water in the well, but it’s flowing faster than you can catch it—what then? Where are all the books about this phenomenon?

The closest Meek can find is writing that connects creative flooding to mental illness, to those manic episodes of creativity that may occur to those with bipolar disorder. Though I have never had an episode of creative flooding that comes anywhere near a manic episode, I have found the idea of creative flooding useful as a way of understanding my always flowing and sometimes excessive and overwhelming creativity. Though I am never completely underwater, I do experience a rather constant low-level feeling of anxiety, like I am walking around in a swamp that refuses to dry out, even as the sun shines. While I am attending to one project, another two ideas will come into my mind. When I type up those two ideas and put them in my “Creative Projects” folder on my desktop, I run across two old ideas neglected inside the folder, and I hear their cries for attention again, and suddenly, instead of feeling great about working on the first project, I feel anxious about the four more clamoring for completion. I am like a pregnant woman who instead of anticipating the birth of one child, finds out she is actually pregnant with quintuplets. Excessive. Overwhelming. Too much.

I suppose this can count as a creative practice of the simplest kind, this collecting creative ideas in a folder on my desktop as they come to me. I developed the practice when I realized that ideas were coming to me that didn’t feel like my ideas; they were coming unbidden—sometimes fully formed, other times as hints—but often as something that felt like more than me, from someone other than me. I deigned this my muse and decided that the only way to repay her generosity was to make something of her offering. She would provide the ingredients for the meal, and I would cook it, and the finished meal would be an homage to her, a propitiation, a way of staying in her favor, ensuring another flavorful idea would come and we would feast again.

Deep creativity is autonomous.

What I hadn’t counted on was just how hungry my muse was. She was voracious. Her eyes were bigger than my appetite. I would barely begin cracking the eggs for breakfast when she would toss out ideas for lunch and suggestions for dinner. The folder grew and grew, became full of more and more bytes, so to speak. The ratio of completed projects to ideas multiplied from 4:1 to 10:1. One year during a three-month sabbatical from teaching, I decided to tackle the folder. It took me two weeks to find the strength and courage to even look inside of it. I filled that time by reading fiction—something I thought would be safe because I don’t write fiction—only to discover that my muse does read fiction and sometimes plants ideas for me inside of those pages. Before the folder swelled too much more, I knew I had to begin.

Once in, it took another couple of weeks to sort through it all. I created subfolders for book ideas, essay ideas, conference ideas, photography ideas, craft ideas, screenplay ideas, whatever was there. I created “Done” folders, and I created “Draft” folders—most were draft folders. I created lists of those drafts in order of how much progress I had made on each of them—projects near completion were at the top, projects barely begun at the bottom. The list was bottom heavy. There was a file, for example, in the “Short Story Ideas” folder titled “He painted only pears.doc.” When I opened it, it simply read, “‘He painted only pears’—from Mary Oliver’s book Our World. Idea: a woman who is completely consumed with a thousand splendid things meets a man obsessed with only one.” I loved this idea; it was exciting to me. The problem was, I simply had no idea what to do with it. To borrow an earlier analogy, it was like my muse had dropped a lovely calabash in the kitchen and said, “Cook a meal with that.” No other ingredients, no recipe, what the hell is a calabash?—file closed.

In trying to sort through these files upon files, I came to see the creativity folder as a bag of microwave popcorn. Some ideas, like “He painted only pears.doc,” were destined to remain like those kernels in the bag that never pop, no matter how long you leave it in the microwave. I threw no kernels away, but I looked for those ideas that were close to popping, and those that were poppable. I felt the excessive, overwhelming too-muchness of it all, and I tried to come up with a plan for what to do now and what to do next. Meek describes creative flooding as feeling “like an air traffic controller in an airport where fifteen planes are all signaling to land at once.” My job was to figure out the landing order of the hovering planes. And, more important and immediate to my psychological health, to figure out a way to deal with the anxiety of having fourteen other planes hovering while trying to land the first one.

Perhaps this is a form of creative practice as well, what we might call “creative management” or “creative control.” This entails processes of organization, prioritization, time management, and viability assessment (is this idea poppable?). It tries to take too-muchness and make it just-enoughness, as in, “Today it is just enough to work on this project.” It is an offensive move against creative flooding—keeping afloat through good management skills; a way of damming up the excessive water for use during a drier season—as well as a defensive move against drowning in anxiety.

Or having to drown your anxiety. In his Paris Review interview in 1957, Truman Capote shared, “I began writing [at 15] in fearful earnest—my mind zoomed all night every night, and I don’t think I really slept for several years. Not until I discovered that whisky could relax me.” Of course, there’s a well-documented if not anecdotal connection between creative artists and addiction, and the more I’ve experienced creative flooding, the more I’ve understood and empathized with its unhealthy tendencies. Of course, the act of creating itself can be addictive and can turn into an addiction. Stephen King states that, for him, writing is a kind of addiction, an ever-present need. “For me, even when the writing is not going well, if I don’t do it, the fact that I’m not doing it nags at me” (Paris Review, 2006). Many writers in particular feed this addiction with creative practices that are the literary equivalent of a regular drinker sitting at the same seat in the same bar at the same time every day. For example, Alice Munro reports writing for three hours a day, seven days a week, from 8:00–11:00 a.m. She shared, “I am so compulsive that I have a quota of pages” (Paris Review, 1994).

Haruki Murakami has a whole routine down. “When I’m in writing mode for a novel, I get up at four a.m. and work for five to six hours. In the afternoon, I run for ten kilometers or swim for fifteen hundred meters (or do both), then I read a bit and listen to some music. I go to bed at nine p.m. I keep to this routine every day without variation. The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind” (Paris Review, 2004).

Maya Angelou also had her routine: “I have kept a hotel room in every town I’ve ever lived in. I rent a hotel room for a few months, leave my home at six, and try to be at work by six-thirty. To write, I lie across the bed, so that this elbow is absolutely encrusted at the end, just so rough with callouses. I never allow the hotel people to change the bed, because I never sleep there. I stay until twelve-thirty or one-thirty in the afternoon, and then I go home and try to breathe; I look at the work around five; I have an orderly dinner—proper, quiet, lovely dinner; and then I go back to work the next morning” (Paris Review, 1990). There’s a bottle of sherry involved as well. She tells the interviewer, George Plimpton, “I might have it at six-fifteen a.m. just as soon as I get in, but usually it’s about eleven o’clock when I’ll have a glass of sherry.” (Reading the Paris Review interviews with writers is obviously my glass of sherry. We’ll have another sip later in this essay.)

I admire this sort of discipline, compulsive as it may be, whether it’s rising at a certain time every morning, like Dennis does, or writing a certain number of pages or words or hours each day or keeping a strict daily routine. I admire it in the way we often admire exactly what we don’t have but think we need. And in examining why I had such a resistance to writing this essay on creative practices, I came to understand that I’m not a fraud, really. I do have creative practices; what I don’t have is creative discipline.

That intuitively rang true to me, but I wanted to understand the difference between practice and discipline better, so I turned to the Internet. On the WikiDiff website, I read, “As nouns the difference between practice and discipline is that practice is repetition of an activity to improve skill while discipline is a controlled behaviour; self-control.” This also rang true, because while I do repetitively create in order to improve myself at it, I don’t do so in a controlled way.

With one exception. I do exhibit self-control when I’m working under a deadline. Rarely does it work with a self-imposed deadline, but it almost always works with an other-imposed deadline (easier to let myself down than to let someone else down, it turns out). For instance, when I was getting my PhD, I wrote three papers a quarter for twelve nonstop quarters over three years; more than 400 pages during that time. In the two years following, I wrote a 385-page dissertation under a looming tuition deadline (and the bottom line of my bank account). I’ve delivered several books to different publishers in time to meet their deadlines. I’ve written newspaper articles and book reviews and submitted screenplays and photographs to contests, all under other-imposed deadlines.

Of course, the psychological trick I’m playing on myself here is that all of these other-imposed deadlines are actually and ultimately self-imposed. No one forced me to go back to school, to write a dissertation, to publish or submit anything. I imposed a project upon myself, then sent it out into the external world for it, for them, to impose a deadline upon me. Would I have written 785 pages in five years without the imposition of academic deadlines? It’s doubtful; and it seems something in my psyche knew this and knew I would need the structure of school to get that writing done.

I once heard one of my academic mentors, Richard Tarnas, say that if you want to get a significant piece of academic writing done, submit a conference proposal. You write an abstract half a year before the conference date and send it off and forget about it. A few months later, you hear back that you were (hopefully) accepted, and you think, “Well shit, I guess I have to write that presentation.” Then you forget about it again for a few more months, and all the while your unconscious (hopefully) is working away at the ideas. Then, right before the conference, you think, “I can either bow out of the conference (bad career move) or I can quickly write and present something shitty (another bad career move) or I can sit down with a great deal of discipline for the next few weeks and write an awesome (hopefully) presentation that becomes the seed for a longer paper or book chapter or another project.” This completely works for me and has become one of my academic creative practices that only requires fits of discipline a few times a year. Then, I will make the time to write—I will carve out the hours and fulfill my quota of words or pages or minutes of spoken word.

Harold Bloom, the literary critic and writer, was asked if there was a particular time of day that he liked to write. “There isn’t one for me. I write in desperation. I write because the pressures are so great, and I am simply so far past a deadline that I must turn something out” (Paris Review, 1991). This creative practice of mine, this self-imposed other-imposed pressure, does mean I write in desperation at times, or in distress, or under duress. But I also find that those moments of pure focus on the task at hand are some of the most joyous moments of my creative life.

In 1922, while writing his first novel, Tropic of Cancer, Henry Miller wrote himself a list of eleven commandments to live by while writing. His first commandment was “Work on one thing at a time until finished.” His tenth commandment was “Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you are writing” (in Henry Miller on Writing). I am forever breaking these two commandments due to my issues with creative flooding, but when I am under a self-imposed other-imposed deadline, I will work on that project until it’s finished, and I will forget everything else I want to write and think only of the project before me. This form of creative concentration is so calming and satisfying that I’ve come not only to trust it but to seek occasions for its occurrence.

I’ve come to adopt this practice in other areas of my creative life. I call it my “Just Say Yes” practice. In the case above, I just say yes to writing an abstract or a conference proposal, that’s all. And that yes, that self-imposed yes, turns into an other-imposed deadline under which I will perform both on time and with a certain degree of quality out of fear of embarrassing myself in front of others or letting them down. I’ve also made it a practice to say yes when other people ask me to do something creative either for them or with them. The director of alumni relations at Pacifica Graduate Institute, Dianne Travis-Teague, calls me and asks me to speak to the alumni at a homecoming weekend, and I say yes, and I choose a topic I’ve been thinking about for a long time but have yet to write about. A former dissertation student of mine, Broderick S. Chabin, asks me to write a foreword for his book Adolescent Males and Homosexuality: The Search for Self, and I say yes, and in writing the piece, I revisit a memory and reclaim a piece of my past. Deborah asks me to write this book with her and Dennis and I say yes, and in the writing of my essays, I deepen into my own creativity. In her memoir When Women Were Birds, Terry Tempest Williams writes, “The world begins with yes,” and that’s certainly been true for much of the world of my creativity.

Much, but not all, because I also believe that our creative world can begin with no. Not no to the muses, for I still hold the superstition that to say no to what they give us would mean they’d stop giving to us and go find someone else who will say yes. No, the no we need is a no to the demands upon our time that take us away from our creativity. We need to say no to the wrong things so we can say yes to the right things.

The challenge with saying no as a creative practice is twofold: discerning what the right wrong things are to say no to and knowing why we don’t say no. In order to do the former, we must understand the latter. Knowing why we don’t say no gives us just enough psychological space to pause for a second and rethink what we are about to say yes to, and then discern the right thing to do on behalf of our creativity. And by “right,” I don’t mean in the moralistic or ethical sense of the word only—though of course that might be part of our decision-making—but I mean another definition of the word right: to be justifiable or acceptable.

The key to whether saying no to something or someone is justifiable or acceptable rests entirely on our personal internal barometer. I can’t tell you whether you should say no to a promotion at work that will keep you from working on your book of poems. Your brother or sister can’t tell you whether you should say no to your favorite charity’s request that you serve on their board of directors, though it will mean you don’t finish that series of photographs in time for submission to the gallery. Your best friend can’t tell you whether you should say no to your wife’s request that you cancel your long-scheduled creative retreat in order to attend her family reunion. Any of those people may find your no neither justifiable nor acceptable. Not everyone values creativity, especially if it’s not rewarded in the marketplace (I’m sure Stephen King doesn’t have to justify saying no when he’s in the middle of a writing project, but if you’re writing a little chapbook of poems that maybe only five people will read if you give them a free copy at Christmas, you may face the “waste of time” argument). Not everyone is compelled to create or finds joy or fulfillment in it, so they may not understand or relate to your creative need for self-expression. Not everyone values creativity in the same way you do, so they may judge you for putting creativity before any number of values they hold nearer and dearer. And there are those who will just be plain envious of you—those without your same talents who are envious of your success; those without your same drive who are envious that you do what they only dream of doing; and those who use their busyness to justify why they don’t have time to create, and who are envious, even resentful, that you know how to say no to protect your time.

So I’ve learned that we all need our own internal barometer, our own “Code of No” that we will honor: “I will say no if I’m just saying yes to people please.” “I will say no if I’m putting someone else’s needs before my own, all things being equal.” “I will say no to any activities that do not make me feel as fulfilled as creating does.” Or, like Henry Miller, we need our own set of commandments, our “No Commandments”: “Thou shalt not make any plans on Tuesday and Thursday evenings so you can draw.” “Thou shalt not indulge your family’s requests for dinners out until after you have saved enough for your new camera.” “Thou shalt not take your cell phone into the workshop when you are working on your projects.”

It turns out that I do have creative practices, after all: writing down all ideas as soon as they come to me, even if they’ll come to naught; systematically sorting through the popcorn kernels of my many ideas and tending first to those most likely to pop; self-imposing other-imposed deadlines; applying Just Say Yes; honoring the Code of No; following the No Commandments. These practices don’t stop the creative flooding. I’ll never paint only pears—my muse is more the farmers market type, and her recyclable bag overfloweth. But I’m not convinced creative discipline would (or could) stop the flooding either. One etymological definition of the word discipline that comes from Middle English is “mortification by scourging oneself.” Though I am sure that getting up at 4:00 a.m. doesn’t mortify Dennis, it mortifies me. Though I would bet writing three thousand words a day didn’t feel like scourging himself to Anthony Trollope, it would to me. So I’ll stop mortifying myself by scourging with an unnatural discipline, which means to say yes to who I am as a creative person and no to being anybody but myself.

Which seems like another good creative practice.

POP!

EXERCISES

Jennifer invites you to these reflections.

If you haven’t already done so in a systematic way, now’s a good time to practice creative management. If it doesn’t sound mortifying to you, take stock of the status of all your creative projects. Organize them like popcorn kernels (never going to pop, poppable, almost ready to pop, already popped), or find another way of sorting them. When you do this, what do you notice? How do you feel? Do you feel creative flooding? Do you feel excitement to finish any projects or bring them into fruition?

If you haven’t already done so in a systematic way, now’s a good time to practice creative management. If it doesn’t sound mortifying to you, take stock of the status of all your creative projects. Organize them like popcorn kernels (never going to pop, poppable, almost ready to pop, already popped), or find another way of sorting them. When you do this, what do you notice? How do you feel? Do you feel creative flooding? Do you feel excitement to finish any projects or bring them into fruition?

What is your relationship with yes, when it comes to your creativity? When do you give yourself permission to say yes? Who supports you in saying yes? Who (besides yourself) challenges you and makes saying yes difficult? When you get in your own way of saying yes, what sorts of psychological justifications do you wrap yourself in?

What is your relationship with yes, when it comes to your creativity? When do you give yourself permission to say yes? Who supports you in saying yes? Who (besides yourself) challenges you and makes saying yes difficult? When you get in your own way of saying yes, what sorts of psychological justifications do you wrap yourself in?

In this essay, I bandy about quite a few terms. What is your relationship to them? Do you experience more creative blocking, or creative flooding? What are your strategies for creative management? Do you have creative control? How does creative discipline manifest in your life? Do you prefer thinking of having a creative practice rather than a creative discipline? Do you work best under self-imposed or other-imposed deadlines, or like me, are you more productive when you self-impose an other-imposed deadline?

In this essay, I bandy about quite a few terms. What is your relationship to them? Do you experience more creative blocking, or creative flooding? What are your strategies for creative management? Do you have creative control? How does creative discipline manifest in your life? Do you prefer thinking of having a creative practice rather than a creative discipline? Do you work best under self-imposed or other-imposed deadlines, or like me, are you more productive when you self-impose an other-imposed deadline?

Can you create something from these reflections?

Jennifer invites you to this practice.

CODE OF NO, OR NO COMMANDMENTS

I believe most of us as creatives want to say yes to our creativity more often, to give ourselves more time and space to follow our creative impulse, as Deborah calls it. Our creative instinct, if it’s strongly held within, is to just say yes. For this reason, I find saying no to be a more psychologically rich practice and also more psychologically challenging. That’s why I want to suggest creating a Code of No, or a set of No Commandments.

This practice is easy on the surface. Creating a Code of No simply means writing down your own rules for when you will say no to something that will keep you from saying yes to your creative project/s at hand. In my essay, I list three that are challenges to me: “I will say no if I’m just saying yes to people please.” “I will say no if I’m putting someone else’s needs before my own, all things being equal.” “I will say no to any activities that do not make me feel as fulfilled as creating does.” Or, if you like the conceit of commandments, write yourself up a list of ten or so No Commandments, your own personal “thou shalt nots.” I gave three examples: “Thou shalt not make any plans on Tuesday and Thursday evenings so you can draw.” “Thou shalt not indulge your family’s requests for dinners out until after you have saved enough for your new camera.” “Thou shalt not take your cell phone into the workshop when you are working on your projects.”

Think of these lists as your creative manifesto. Keep them handy, not only in your creative space but in all spaces where you’re likely to be challenged by the requests of others (in your phone, by your computer, on your desk at work, etc.). You may push the practice further by doing a weekly check-in. At the end of each week, look back over any codes or commandments you might have broken and ask yourself why. And when I say above that this practice is easy on the surface, this is where it gets more psychologically challenging, as we try to understand more deeply why we sabotage our own creativity, why we are impelled at times to say yes to others and no to ourselves.

If you don’t like the emphasis on no here, you can do the same practice in the affirmative. Write a Code of Yes, or your Yes Commandments. Or better yet, write both. Really flesh out the reciprocal relationship of yes and no to your own creative fulfillment.

One Writer’s Insistence on Resistance

Dennis

Sometimes I feel that I would like to stop writing, precisely as a gesture of defiance.

—THOMAS MERTON, Echoing Silence

I begin each morning by writing in my journal for fifteen minutes. I write about, for example, what wishes to be remembered from yesterday. Writing serves as a way to revisit what was; it changes my own life events into a formed memory that adds to my sense of my life’s history. I then treat myself to reading a favorite poet’s work. Currently my go-to poets are Jorie Graham, Mark Strand, and Rumi. If a line or an image from their verse provokes a line, a word, or an image in me, I let it run; often a fully birthed but rough poem is the consequence. This daily ritual, along with frequent readings on meditation, dispose me to the day that will more often than not include writing something additional, even if it is only twenty-five emails.

Deep creativity is responsive.

Writing clears a space in me, like the clear space of the blank page, which used to terrify me with its stark emptiness that scowled back, daring me to fill it with words. Now the white space of the computer or the blank space of a writing tablet on which I often write down in longhand ideas or quotes from what I am reading, laced with my own thoughts, reads like an open invitation to inscribe who and what I am, with interest. Anything I write, on whatever subject, always ends by giving my own life a form and a perspective that I did not possess before. I believe we are always writing about ourselves or at minimum giving shape to the personal myth we engage during any writing project—emails and texts included.

I do not write by choice; it is a vocation, a work, a way of living. I have improved as a writer over time, but I learn more about the practice with every piece I write. If I am very lucky, places that I send my writing to respond that they wish to publish it, but not without a handful of edits for me to include first. I study these edits with a magnifying glass to see what editors saw in my prose that needed repair but which I could not discern. Having my writing taken that seriously is a joy and a challenge, a privilege and a pursuit, even though in my ego-stricken early days I found insulting and demeaning: “What do you mean, ‘Not quite good enough!?’”

I used to find the process of writing intimidating, even when I received high marks as an undergraduate and graduate student; it was not unusual for me to inhale a pack of cigarettes down my throat to reach the end of a single term paper. Writing my first academic essay as a PhD candidate at the University of Dallas in the mid-1970s was a threshold I worked hard for years to cross: a smoke-free essay, this one on phenomenologist Edmund Husserl. I felt at that moment that I deserved at least beatification in the Catholic Church. My lungs remained clear until I began teaching at the university level; then the furnace food returned. Running ten-kilometer races for years weaned me from the weed, and when my hips gave out and needed replacement, lap swimming kept the southern leaf at bay.

But anyone who writes will sooner or later bump into what has been called and accepted as “writer’s block.” Its connotation is something negative to be gotten past, over, under, or through. What is blocked is progress in writing and we can add, in thinking or imagining. It may be a failure of imagination, but I think there is more to it and do not believe it is a completely negative moment in the struggle for clear expression. As I do with any writing project, like this current one, I use the occasion to muse, discover, uncover, or recover some of my own behaviors in writing. I spent some time this morning, for instance, walking through the thousands of books that line my home study and our living room—7000 books at last count—gad! I pulled from the shelves books on writing and related topics. I promise to use only a few of them in this essay, but I find reading about other writers’ habits, hang-ups, harangues, and successes in their own writing immensely consoling.

One book that almost escaped my notice as I hunted down titles is The Art of Writing: Teachings of the Chinese Masters; I wanted to read about non-Western writers on their craft. What a lovely little volume, I thought as I paged through it one morning. I found in the preface this question posed by the writer Wang Jiling: “What’s the difference between poetry and prose?” The poet Wu Qiao responded that the writer’s message “is like rice”:

When you write in prose, you cook the rice. When you write in poetry, you turn rice into rice wine. Cooking rice doesn’t change its shape, but making it into rice wine changes both its quality and shape.

What a gem in its elegant simplicity. That was only the beginning. As I thumbed my way through the poetry and prose, I was arrested by a fine little poem called “Writer’s Block” by Lu Ji, author of the volume. We learn in a footnote to the poem that the six emotions referenced in the first line are sorrow, joy, hate, love, pleasure, and anger. Sometimes a seventh, desire, is added. Such elegant complexity so characteristic of Chinese art gathers here. Arrested affect is the beginning of the end for a writer; one is forced inward, away from the page or the screen, because the impediment is within. No flow, no fullness; hollowness is all. I cannot help but imagine the image of the spider spinning the silk out of itself, as the writer must acknowledge this string of silk words spinning from within. Finally, we may not be able to identify with any precision what brings on such a pause, a resistance, or a stampede on the creative process. I really do not think we have to find the secret of the suffocation but rather to learn to integrate it into our whole person.

I avoid the position in creating that somehow I own what I create; I think that disposition is neither correct nor agreeable. What if we assume the disposition of Socrates in Plato’s dialogue the Theaetetus when he tells his student, the young and searching Theaetetus, that he, the great philosopher, is only a midwife to ideas, that his role is one of birthing them, of pushing them into the world, preferably head first, though one takes for granted through the midwife image that some ideas will be breached, perhaps pushed back in, to be turned head up and redelivered. What an image for editing and revising!

Among his almost two-million-word journals, Henry David Thoreau wrote in The Faith in a Seed of the biologist Carl Linnaeus’s binomial system for classifying plants and that such an activity “was itself poetry.” Later he wrote in that same work: “Facts fall from the poetic observer as ripe seeds.” He learned over time that what one writes about is what one’s wonder leads one to. I cannot say if he ever suffered the agony of writer’s block.

BLAMING “DEFEET”

Something about the phrase “writer’s block” rings false for me, as I suggested above. It feels like something is in the way and all that is needed is the right liquid clog remover to unblock it, or a plunger that, pumped with enough force, will clear the writing pipes and allow the ink to flow easily once more. It is a negative state that must be overcome by some positive force: attitude, energy, stamina, or perseverance. I want to speak instead of a block as a form of resistance signaling to us something we might best heed, for it is seeking a response from us. I want to imagine that when I am resisting something in the writing, I am being offered a bit of rhetorical feedback to take a pause, rest, reevaluate, renew, or re-vision what I am up to. I believe the subject matter itself has its own consciousness and spots something I am missing, perhaps a direction it wants to move in, expose, reveal, or unveil, and that my current writing strategy is rupturing and so impeding that process. I see this often with my students in dissertation writing; I discern it frequently in myself. So I ask, not what is resisting me but what am I resisting? A few questions and observation here: Are my words failing to materialize because something in the theme is failing me or I am failing it? Am I being invited through the resistance to take a break, assume a pause, so to carry the theme’s residue around for a few days? Is the resistance signaling to me that I am rhetorically tripping over my own feet in a temporary “self-defeet”? As I consider the Buddhist image of how addiction can appear, am I trying, in my forced prose, to keep things moving, actually licking honey from a razor’s edge? Is the resistance feeding or pointing out one of my own addictions that carries over into writing? Is this a necessary part of the pilgrimage of writing that tries to wed the thoughts or images in my head with what the fingers are wishing to transcribe on the page or screen? Is Resistance a character in a screenplay where I feel a checkmate looming on the horizon? Is the drag on the prose a signal that I am out of my depth or not deep enough into it? Am I wriggling like a tadpole in the warm muddy shallows of my theme rather than risking a dive into deeper waters—where darkness and absence of clarity of a clear path await me? Is the stopgap the appearance of contradictions that loom before me like too many cars trying to get by at a busy intersection when the traffic light malfunctions? Lights out, chaos on.

Deep creativity is reciprocal.

Anyone reading this can add their own questions to keep the quest fresh. The above list comprises a handful of mine that I have wrestled with, one by one, over many years of writing.

PROMPTING THE PROSE

To come to some conversational place with the material, I might try a modified form of a process that C. G. Jung developed to personify the object, thing, idea, or image being considered to enter a conversation with it as a living being. He called it “active imagination.” Here, I imagine a dialogue between my frustrated self at an impasse and the material, now personified:

Me: Who or what are you that has me pinned down right now in my prose pilgrimage?

Subject Matter: I am confused about where you are headed and what is motivating this direction. So I put the brakes on the pilgrimage to give you a moment to reassess your intention.

Me: I don’t see where there is a problem, so I am stymied by what has entered center stage to resist me, my antagonist, my nemesis, and my crucifier of deadlines.

SM: You are already caught in the fantasy that this is a waste of time and that you should get on with it. But under the belief that not only is less more, but time out is time saved, I have pulled the plug on your energy as well as your will to continue.

Me: Fine, but how long will this take? I say this because I am wrestling with the insight you have put in my path. I’m not saying you are wrong, but I have to admit I am struggling to accept it.

SM: Fair enough. Do something else for a while; unplug and find something you really enjoy doing that you have been putting off for some time because your schedule allows little room to play, to cavort, to drift, and to engage the world differently as a way of enjoying a respite.

Me: Okay, I can live with that. Let me give it a try and see what happens.

SM: If you do this, you must promise not to engage me for that duration. Let me gather myself into a new form for your evaluation. Then we’ll talk.

This dialogue could continue, but you get the idea. Even making this up as an illustration, I felt something stir in me about my own writing resistances.

I also remember, in rereading and teaching The Divine Comedy, how often Dante addresses the reader regarding the work he is struggling to write—over thirty times throughout the lengthy epic poem—and he includes us in it as a character. He will ask, for example, how we are doing with his poem and whether we are able to make sense of it and, just as often, he asks if we can complete it for him because he cannot find the language to express fully the phenomenon he is confronting at a particular moment. In at least one instance (in “Purgatorio,” canto 33) he ends by saying that he has more to write but the form of the canto—its number of lines and its number of words—forbids him from writing any more. So the form of the poem—its symmetrical limitations—not what Dante has to say, dictates how much he is allowed in any and every canto of the one hundred that comprise his journey. One sees after a few readings that the poem is as much a record or a chronicle of his own writing strengths and limitations as it is about anything else on Dante’s spiritual pilgrimage. Indeed, The Divine Comedy could be used as a major guide in writing courses and creative writing programs.

Returning to Lu Ji, in one of his poems, he writes about how inspiration can come in a flash, then flare out unrestrained. From a flash to fluidity. To be inspired is to be inspirited; writing, painting, composing, crafting all assume their own life force—one needs to hang on, let go of the reins, let it flow, and only later, in retrospect, see what has been created out of oneself as well as from the aid of other forces. Inspiration is like a gush that, if it appears during a fallow time of shallow inclinations, will wash things clean. The poem reveals that this momentous surge is instinctive, unrestrained, wants to follow its own pulse and heartbeat, and can be excessive or abundant, depending on perspective.

The elegant Linda Schierse Leonard’s book The Call to Create: Celebrating Acts of Imagination should be desktop material for anyone who creates. As a longtime Jungian analyst and teacher, Leonard offers another rich image of this mysterious process of creativity. Early on she relates a dream she had before beginning to write her book. In the dream she found herself surrounded by twenty-five wild beasts. There was no exit, no escape hatch; she realized that the only response available to her was to “learn to feed them and discover how to relate to each one.” And then the moment of her revelation: “When I woke up, I realized that the wild beasts symbolized an abundance of instinctual creative energy. If I did not feed these forces and learn to honor and respect them, they would devour me. I need to learn how to live in the wilderness.”

I believe she is speaking of inspiration; a herd of wild beasts, with their unlimited energy, is an apt image for carrying this field of inspiration forward. Such enthused creativity, she goes on to suggest, is at heart “an adventure of the soul in its quest for meaning in this earthly life.” One must, however, be willing to enter the natural order, to follow the rhythms of nature and shed some of culture’s strictures. Recontacting the natural order is a promising way to come to some bargain with resistances that end-stop the creative process. Hiking in a favorite forest, a park, or a landscape that allows one’s feet to touch earth instead of asphalt or concrete is an effective way to free something up that has lost its natural impulse, rhythm, desire, or yearning. I find that it works. My “nature of choice,” however, is often a motorcycle ride on my Harley-Davidson Electra Glide Classic through the ranch roads of the Texas Hill Country that places me in the natural order with a cultural artifact between my legs and in my hands. All I can say is: it really works. I return to my project more balanced and focused as a result of this alternative journey. For if creating is anything, it is a journey inward even as the tools of our crafting point outward.

Leonard’s book is also a balm for those wishing to create, are creating, or have created, but who need further work. Her chapter on doubt, especially as it appears embodied or at least voiced in “the Cynic,” is hugely helpful to read and meditate on in order to integrate these presences and then to counter them with renewed “Courage,” a heroic helper that can inspire a new direction.

Finally, as to other possibilities that might serve the checkmated creative person, I refer to a book I was reading coincident with writing this essay: Myth and Reality by the world-famous mythologist and cultural critic Mircea Eliade. It had hidden on my bookshelf for years and called to me as I rushed to catch a flight to Santa Barbara, California, to teach. I mentioned earlier that when I find myself resisting more than actually writing, I pick up something to read that is not on the subject I am writing about. Doing so almost always opens doors to my subject matter from an oblique angle. Such a process was true in this instance. I want to share a couple of examples before closing out this series of musings. They take a mythic turn toward resistance in creating that I am trying to implement.

Eliade’s writing often develops one of his favorite themes: the power of retrieving origins in the stories of various tribes, peoples, and civilizations; it points to the beneficial effects of reestablishing such contact. He outlines how in many tribes, at the birth of a child, the resident shaman, artist, or priest recites over the newborn, before it has had a chance to imbibe any nourishment, the story “of the origin of the cosmogony and of the tribe’s mythical history.” He has investigated this practice, repeated with uncanny commonality through history, and has discovered that in tribal mythologies, a newborn “cannot ‘begin’ anything unless it knows its ‘origin,’ how it first came into being.” Then, when it takes in its first nourishment, the child “is ritually projected into the time of ‘origin,’ when the food it is to eat now and as it matures, first appeared on earth.”