Chapter 4

THE HELLIWELL BREWERY, 1820–1847

If the Doel and Farr breweries had in common their support for the reform of the political system in York and the direct actions that they took in order to support that reform, then the Helliwell brewery was the polar opposite. There are many reasons for this, but the most important has to do with a small difference in lead time. There was not a great difference in the fortunes of these families in England, but the rapid development of Upper Canada in the early days of the nineteenth century meant that political allegiance could be determined simply by the year that you arrived.

The Helliwells had come from Todmorden in Yorkshire, which was not famed for the quality of its brewing at the time. If anything, Todmorden’s production was a mixture of agriculture and weaving, with mills devoted to both industries. By the turn of the nineteenth century, agriculture had become less prominent, and the production of woolen cloth was being supported by the advent of toll roads and a newly completed system of canals. Before the mechanization of the textile industry in Yorkshire, there was a living to be made even if you were not the owner of the mill. With the adoption of that machinery, wages fell so ruinously low that West Yorkshire became a significant site of Luddite revolt, with workers smashing and burning their equipment.

The Helliwells were mill owners, but that status within a rapidly changing society was no guarantor of future success in a country with a booming population. Thomas Helliwell himself had six children by the time the Luddite revolts broke out in 1812. The previous year, his youngest daughter, Elizabeth, had married a local tinsmith named John Eastwood. Subsequently, they decided to move to Upper Canada. John Eastwood settled in Lundy’s Lane and engaged in trade across the river with Buffalo. The letters home must have painted a picture of a land with possibilities that did not exist for even a well-to-do milling family. The Helliwells came to Upper Canada in 1818.

At the time, the area around Lundy’s Lane and Niagara had a greater population than the town of York and was a better seat of business for those with a trade. Relations with the United States were once again peaceful, the question of territorial boundaries having been settled. Thomas Helliwell would become a shopkeeper and eventually a distiller in Niagara, realizing that the sale of whiskey was more profitable than the sale of general goods. In those days, whiskey went for one shilling per gallon at York. Helliwell must have been restless with the lack of consuming work. Now fifty years old, he had spent his entire adult life as a miller, and while distilling was certainly a profitable trade, it wasn’t likely to provide for his family.

Seeing the possibility of the town of York, the Helliwells and the Eastwoods settled on the Don River to the northeast of the city. John Eastwood named the settlement after their home for the striking resemblance the Don Valley bore to that part of Yorkshire. At the time the Helliwells had a homestead constructed in 1820, they owned a significant tract of land encompassing nearly a quarter of what we think of as East York—almost everything northwest of the intersection of Donlands and the Danforth. At the time, the Don Valley was home to all manner of wild creatures. The sheep the Helliwells kept were dispatched by wolves on their doorstep.

The majority of the picture we have of the Helliwell brewery is due to the fact that the second-youngest son, William, was a dedicated diarist. Taking up pen in 1830 at the age of nineteen, William had been in Upper Canada since the age of seven. He would have been just barely old enough to remember his native Yorkshire, and as a result, he grew up knowing only the society of Upper Canada. His diary provides us with huge amounts of detail societal, professional and personal. It is a unique insight into brewing in the early nineteenth century in North America and into Toronto’s development.

By the time William began to keep a diary in November 1830, the Helliwell brewery had become a successful concern. While William was the brewer, the organization of the family interest lay with his older brother Thomas, who had been a successful businessman even prior to leaving Yorkshire. Thomas Helliwell Sr. had passed away in 1823. From the earliest days of the brewery, the Helliwells were exporting beer to the head of the lake at Niagara, the relationships they had formed there during their brief sojourn proving invaluable to their interests.

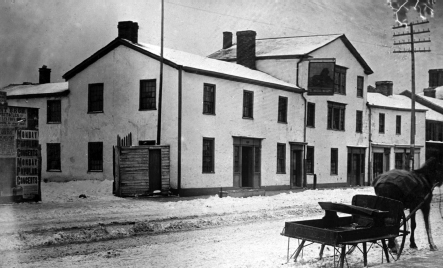

The Todmorden Mill still occupies the property owned by the Helliwell family, although the mill itself was built by the Taylor family. The majority of the families in the Don Valley were eventually related by marriage. It was an insular world. Toronto Public Library.

Within Toronto, Thomas Helliwell was the force behind a number of businesses, including tinsmithing, a trade in which his father had entered with John Eastwood and which his younger brother, John Helliwell, now operated. While it was certainly the case that brewing made up a decent part of the family’s trade, they were also related by marriage to the Eastwoods and the Skinners in the Don Valley and would, as a result, have commanded a large portion of the production capacity of east Toronto. There were paper mills and gristmills upstream from the brewery.

Taken all together, it seems a natural extension to acquire a wharf for shipping, which the Helliwells did. A successful businessman with a deep understanding of trade in Upper Canada, Thomas Helliwell would become a director of the Bank of Upper Canada in 1834—a greatly desired position for a businessman in a society where a lack of currency in circulation could make doing business difficult. At this point, Thomas would have been living downtown in a house that had originally been built for Dr. Thomas Stoyell. He was clearly regarded as the head of the family.

The Union Hotel was also known as Stoyell’s Tavern earlier in its existence. It was not purpose built as a tavern, acting as the residence of Dr. Thomas Stoyell and, subsequently, Thomas Helliwell during his tenure with the Bank of Upper Canada. Toronto Public Library.

William Helliwell’s home still stands near the Todmorden Mill. It is a rare example of adobe brick construction in Toronto, having been constructed long before the Don Valley Brick Works had become an established property. Toronto Public Library.

By the time William began keeping records of his involvement, the brewery had been in operation for a decade. His elder brother Joseph was primarily interested in farming but would watch the homestead while William was away. His younger brother Charles would have been thirteen years old and learning the trade. William, having been brought up as a brewer, was endlessly interested in the specifics of running the brewery, frequently making notes in his diary about the amount of extract in a batch of wort or about the scheduling that took place from day to day.

The brewery would operate from about early November to late May. During the season, William would mash in slightly before dawn, expressing consternation when he would miss his mark. The brewery had its own maltings, and loads of barley had to be brought in so that beer could be made, a task frequently made difficult by the nature of the river valley. It is not for nothing that the most frequent observation in the diary is “roads very muddy.” The maltings were carried on separately from the brewery, overseen by other employees.

The brewery would have used six-row malt, the main variety that was grown in Ontario before the twentieth century. The hops would have been either a native variant like Cluster or Goldings, depending on whether English hops were available. In later years, the Helliwells would plant a significant hop yard. While we have little idea of the yield that the hops might have provided in the Don Valley, we can estimate the size of the yard itself from the number of poles used for trellises. In 1834, it would have been nearly 450 poles, meaning that the footprint of the hop yard would be nearly ten acres at a conservative estimate.

We know from his mention of a visit to the manufacturer while he was in London, England, that William Helliwell was using a particular scale of measurement for his wort. It was a Dring and Fage saccharometer of the kind that was widely used in England. Rather than specific gravity, the saccharometer measured pounds of extract per barrel of liquid.

The measurement, referred to as beer gravity, tells us that he was producing finished wort at about thirty-three pounds of extract per barrel. In modern terms, that is an original gravity of approximately 1.090. Assuming a yeast strain capable of the output, William Helliwell’s beer could have been between 8.5 and 10.0 percent alcohol. This was not very much stronger than average at the time. For the Loyalists who were used to the wheat wines of upstate New York, it would have been ideal.

By the brewing season of 1830, the Helliwell brewery would have been producing about ninety barrels of beer per week, or about three thousand barrels of beer per year. For context, the Helliwell’s operation would have been larger than many small breweries in Ontario today. The ale would have been fermented in a number of tuns, with conditioning taking place in individual barrels or puncheons.

What was not ideal was the location of the brewery. The Don River may not look very impressive in terms of its flow, but during a particularly hard thaw, the risen waterway could prove destructive. March 1831 was just such a season. Not only had the drainage for the maltings backed up into the malting floor, but it also swept one hundred bushels of malt away. The entry for the next morning reads, “All the forenoon we spent all hands in getting the mud and malt off the floor and putting it into the mash tub and washing it. The river continued to raise all day and presented a spectacle truley sublime to see. The trunks of trees and flaiks of ice passing down the rappid corrant it took the mill dam away and most of the fence that borderd on the river.”

The power of the mills along the river to drive industry was severely compromised. The stillions that held the fermenters in the cellar were waterlogged. The yeast (or what remained of it) would not survive the summer, and replacement would have to be sought from John Farr at the other end of York. Transporting barrels downstream for sale was no longer realistically possible. At the age of twenty, William Helliwell found himself in charge of a brewery that required significant improvements due to the sudden violence of the river.

Yet William Helliwell was up to it. Having come from the professional classes in England, he was possessed of a work ethic, and even at nineteen years old, he was something of an autodidact. There was a duality to his nature. In many ways, he was the consummate professional; one of his first journal entries has to do with borrowing a treatise on the methods of gauging and measurement. He attended the Mechanic’s Institute in York for physics lectures on fulcrums and levers and spent much of his spare time in the study of trigonometry and algebra. The notes that he kept are detailed enough that nearly two hundred years later, we’re able to reconstruct details about his brew house efficiencies.

At the same time, William Helliwell was something of a Romantic. When not improving his ability in mathematics, he was a great one for poetry, leafing through the works of Byron. He was caught up not only in poetry but also in the cult of hero worship on which English nationalism built its empire. He read Robert Southey’s Life of Nelson and would put off work to cheer John Colborne’s arrival in York. Colborne had, after all, become one of the heroes of the Battle of Waterloo by flanking and routing the chasseurs of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard.

This combination of life as a privileged child and a nostalgia for a world that he had never really known led to a kind of sweet naïveté about matters political. William Helliwell was directly involved in two of the most important events in political life in Toronto in the 1830s. On January 2, 1832, William was present at the Red Lion Inn for a local election but was apparently unaware that it was also to be the by-election that would return William Lyon Mackenzie to power: “[W]hen I got there I found a great assemblage of People and Ensigns flying and Bag pipes playing I was very soon surprised with the People shouting with caps off and completely at a loss to account for it but I was not kept long in suspense for presently a large slay drawn by four Horses and having a frame fixed on it to support a second floor crowded with people made its appearance amid roars that would deafen a person. MacKenzie here began his harangue but my attention was called off to the town meeting.”

The Red Lion Inn was situated on Yonge Street and acted as the centre of Yorkville, being the site for dances, elections and banquets. It stood through the greater part of the nineteenth century, eventually being torn down to make way for Britnell Books. It is now a Starbucks. Toronto Public Library.

William Helliwell was voted path master of the road that ran near his brewery at the town’s election, but the real excitement of the evening was Mackenzie, of whom Helliwell did not think highly:

I left the meeting and went out to hear McKenzie hold forth. He was reading a pamphlet containing all the grievances or imaginary grievances that he could cull from all the acts of the assembly for the last five years. He made very severe remarks on his Excellency Jude Robinson, Arch Deacon Strachan and others. He likewise gave us an account of his being expelled the Bank the Agriculture Society and the House of Assembly with an account of the ship wreck of the waterloo steamer on the Saint Lawrence where he was very near being expelled from the World altogether.

Mackenzie won reelection that night at a margin of 119 to 1 by casting himself as the martyr of Upper Canada’s liberty, although William Helliwell was almost certainly right to doubt the veracity of all his statements. He also summed up the tone of the evening: “Young Street from the Red Lion to York was full of people and slays and every slay was full and all roaring out hurrah for MacKenzie.” While Mackenzie would find himself expelled from the assembly again five days later, his popularity was established.

The Red Lion Inn in winter illustrates an important point about the manner in which people travelled in Victorian Toronto. Sleighing was not only an important means of transportation but also a favored recreational activity in the city’s valleys and along its shorelines. Toronto Public Library.

William Helliwell did not pay much attention to the politics transpiring under his nose because the road he had been named path master of ran by the Bright family’s home. Their daughter, Elisabeth (Betsey, informally), was the object of his affection and was the subject of a lengthy courtship. Unfortunately, she was to be married to an older gentleman named John Elliot. William behaved in the manner that can only be affected by a provincial lovesick twenty-year-old who has made a point of reading Byron. His attentions, from the point of view of a modern audience, were upsettingly obsessive. The persistent declarations of affection are available to read in the diaries, as all of the notes that passed between William and Betsey were copied by hand into his journal. The less said about the poetry the better.

Betsey Bright finally acceded to marriage with William Helliwell just prior to a scheduled trip to England. There were no breweries much larger than the Helliwell Brewery in York, and in order to learn more about his trade, William Helliwell would have to travel. He did this with some regularity anyway, having visited Peter Robinson in Newmarket when opportunity presented itself and Joseph Bloore almost daily on his way to York on foot.

The journey would take him through New York State and on to London, England, to his family’s home of Todmorden. At nearly every stop, he would engage his observational skills on inspecting the local breweries. There was Nathan Lyman’s on Water Street in Rochester and Fiddler and Taylor’s in Albany. William was skeptical of the twenty-thousand-barrels-per-year production claim. At Boyd’s brewery, he noted that three kilns was almost certainly too many for the amount of malt the floors could produce. When not occupied in that pursuit, he would read Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad.

In London, he toured the Nine Elms Brewery in Wandsworth (site of the London Beer Flood of 1814) with the brewer. In his tour of Barclay Perkins, he noted the vast cellar and improved method of steam cleaning the casks. His tour of Calvert and Company takes up several pages, but a brief description of the Porter Brewery highlights the difference between brewing in England in 1832 and his own setup in York:

The first place he took me to was the Mash tub which is about 30 feet in diameter and eight feet deep They had just stopped the machine. There was 120 quarters or 960 Bushels of malt in the tub. The underback is about 15 feet square and 6 feet deep cast iron. One of the coppers holds 1200 Barrels and has a machine drove by steam to rouse it and keep the hops from settling to the bottom. The other copper is not quite so large. The Hop back is about 30 feet by 15 & 5 feet deep all cast metal false bottom and all. There is a reservoir for water on the top of the House as large as a quarter acre field all Iron.

The tour was a success, and after visiting his extended family at Todmorden, William Helliwell returned to York by way of Liverpool. He put his observational skills to good use and was brewing Porter in addition to ale in very short order. Brewing in York was physically demanding work, and one needed to be physically brave in order to do it. While injuries were commonplace, some required incredible toughness to endure. Lest you think William Helliwell a dandy for favouring Romantic poetry, it is important to relate that he was no physical coward. This is evinced by his self-treatment during a particularly nasty accident:

Commenced Brewing!!! But alas I was not destined to finish. About one o’clock when I was about to start the worts from the copper and had just put the fire together for the purpose of letting burn out before emptying the copper I had only just turned my back when the bottom of the copper gave way and out rushed the Boiling Wort and struck me on the back of the legs and knocked me down. But fortunately I had the good fortune to fall on some wood which kept me out of the boiling fluid which covered the floor. I retreated as soon as possible into the Granary and pulled off my pantaloons and shoes and hose and with them the skin off my legs and ankles. In this state I came through the window by the Mill and round to the House where as soon as possible was applied Linseed Oil and lime water and continued till about six oclock. I began to be faint and was taken to bed and a doctor sent for who when he came said that they could not have been better taken care of.

Although he lay incapacitated for sixteen days, it would not deter him from following his calling.

The Rebellion of 1837 would make him prove his bravery once again. Unlike today, news in Upper Canada in 1837 travelled as fast as people. It is easy to look back on the 1837 rebellion dismissively now, given that it came to a single volley of gunfire in Yorkville. At the time, no one knew that would be the case. No one knew how many rebels there were. No one knew exactly how they were deployed. The uncertainty was enough to close the majority of businesses in Toronto. The Helliwell Brewery was especially vulnerable, as it possessed one of the only bridges across the Don River and was therefore of strategic importance.

On December 5, 1837, William Helliwell found himself returning from Niagara on a collection tour. He hurried home as quickly as possible. While Betsey had not been left alone entirely, she was nine months pregnant at the time and was unable to travel even the short distance to Toronto. No doctor would make the journey to the brewery. In another circumstance, one might simply have burnt the bridge and retreated to the city. As it stood, the brewery employees kept guard, and William Helliwell would brave the uncertainty of the Don Valley to be sworn in as a special constable.

On December 7, William found himself at the Parliament Building to acquire shot and a musket and ended up being made impromptu quartermaster in charge of powder and shot for the government of Upper Canada. Over the course of the next two days, he cast nearly two thousand rifle balls to arm the loyal citizens of Toronto.

By December 9, two thousand rebels had been captured. By the eleventh, one thousand troops had arrived from Cobourg. By the thirteenth, William Helliwell was finally able to move his wife to her parents’ house at the east side of the Don River Bridge. On the fourteenth, he was once again a father.

The Helliwell Brewery burnt in 1847, and William Helliwell would give up his career as a brewer to become a miller near Highland Creek in Scarborough. It is possible that his heart was no longer in his work. Betsey had passed away in the early 1840s. He would live until the age of eighty-six and keep a diary until the end of his life. Whereas we know comparatively little about the character of some of the other brewers of Toronto’s nineteenth century, I can suggest to you that if brewing in Toronto can be said to have such a thing as a patron saint, it may as well be William Helliwell. He was intelligent and inquisitive. He was focused and observant. He was scholarly and cultured. He was brave and loyal. One could not hope for a better role model.