Chapter 8

JOHN SEVERN BREWERIES, 1832–1886

John Severn was born in Wessington, Derbyshire, in 1807 and was a later arrival to York. He would immigrate to Upper Canada from England in 1830 at the age of twenty-three. At the time of his arrival, he was not a brewer by trade but rather set himself up as a blacksmith at Richmond Street. The brewery property that he would occupy was owned by a man named John Baxter, and it was a fairly bare-bones red brick structure when Severn took it over in 1832.

By that time, a great deal of the property around Yorkville was already owned by Joseph Bloore and William Botsford Jarvis. As such, John Severn would have to content himself with a nine-acre parcel of land just northeast of the tollgate at the foot of Davenport road, just up Castle Frank Brook from Joseph Bloore’s brewery. Severn’s brewery would become his livelihood, and he’d spend much of the next twenty years expanding it into a going concern.

By the 1850s, taking into account the destruction of several of the local breweries by fire, it would have been the largest in the environs of Toronto. It specialized in ale, Porter and Half and Half as a mixture. Charles Pelham Mulvany wrote in 1885 of the height of the brewery’s production that “[t]he buildings occupy, brewery 80x225, five storeys; malt house 35x115, containing three storeys. Cellar room the whole extent of the brewery. Employ five hands in the bottling department, five in brewery, three in malt department, two travelling salesmen and one clerk.”

Severn’s brewery was capable of producing six to seven thousand gallons of beer per week in 1867 with the help of a fifteen-horsepower steam engine driving the mill. Assuming a thirsty public and year-round production aided by the icehouses built nearby on Castle Frank Brook, that would have translated to nearly 10,000 barrels of beer per year. While it’s very difficult to say when production would have peaked, we do know that by 1885 it had declined to about 6,500 barrels, likely due to the mammoth breweries that had sprung up in downtown Toronto. It would appear that the bottling room was only added in 1882, meaning that the brewery had limited plans for exporting its product to other large markets, where bottling would make sales through licensed establishments possible.

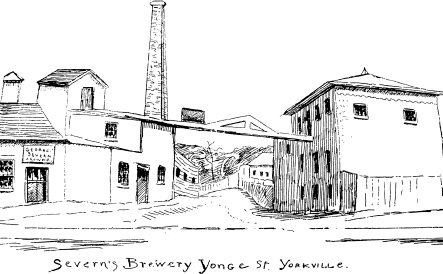

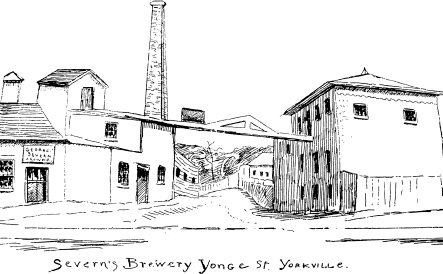

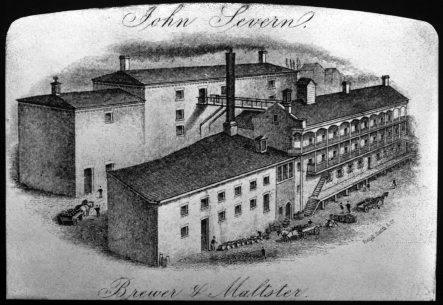

Severn’s Brewery as portrayed in John Ross Robertson’s Landmarks of Toronto. This view would have been from just across Yonge Street, north of where the Masonic Temple stands. From John Ross Robertson’s Landmarks of Toronto.

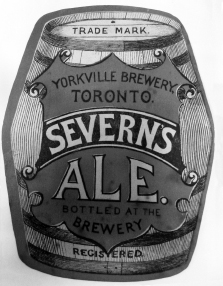

Aside from being a brewer and philanthropist, Severn’s other role within the community was as a local politician. Upon the incorporation of Yorkville in 1852, he was one of the first five members of the elected council for Yorkville. The village’s crest, which can be seen above the door of the fire hall at 34 Yorkville Avenue, represents his trade with a beer barrel. By that time, Yorkville had become Toronto’s first suburb, and an omnibus line, the city’s first public transportation, ran from the Red Lion Inn to the St. Lawrence Market.

This label for Severn’s Ale from the brewery in Yorkville makes a conscious effort to replicate the crest of the town of Yorkville. The scrolling at the edges of the crest on the barrel match up perfectly. The barrel is actually Severn’s symbol on the town’s crest. Molson Archive.

John Severn was unlucky in marriage. Throughout his lifetime, he had at least three wives: Jane, Aureta and Jane Wilson. His numerous children would require a not insignificant fortune in order to make their way in the world. From the first marriage, he had three sons: George, Henry and John. His second marriage added William to the fold. Severn’s brewery was clearly profitable, and with his knowledge of the brewing trade, he set out to provide each of his children with a brewery of his own.

John Severn and his son John left Yorkville in 1850, leaving the brewery on Castle Frank Brook to George and Henry Severn, the two eldest sons. John took his skill as a brewer to where it was in the most demand: the thirsty gold rush town of San Francisco. This was a time prior to the culmination of the transcontinental railroad, and the voyage would have been made by sea. John and his son entered into a partnership with Jonathan Peel, a recent transplant from England and nephew of the late Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel. The name of the brewery in which they invested is lost (it is tempting to think that it may have been the Empire Brewery, given the pedigrees involved), but it is clear that John Severn lost interest upon the death of his son.

After a brief sojourn in England, Severn returned to North America, stopping briefly at his home in Yorkville before making his way to Davenport, Iowa, in 1858. Davenport may seem an odd choice, but it was at the top of the steamboat routes for the Mississippi River, and the trip to Davenport was not particularly arduous due to lake boats and eventual rail connections from Chicago. John Severn purchased an existing brewery that was situated next to the Mississippi and renamed it the Severn Ale Brewery. Throughout these expansions to the family business, there was not much change in the product that the breweries churned out. These would play to the strength of the family’s experience with ale and Porter. The Davenport brewery would go through the hands of all of Severn’s remaining sons, and it was where George and Henry found themselves when John returned to Yorkville in 1864 to reclaim from them the brewery that he built.

John’s youngest son, William, would find himself with a brewery of his own after a brief period as an apprentice in Davenport. It was opened in Belleville, Ontario, in 1874 and would last until 1888—two years longer than the original brewery in Yorkville. For a brief period in the 1870s, John Severn actually managed to fulfill his dream of seeing all of his sons operating breweries of their own. Perhaps as a result of the expertise that he displayed, he was made the first president of the Canada Brewers and Maltsters Association in 1878.

For all of the effort that went into creating regionalized breweries for his family, including brief periods as a hop factor in the early 1850s and tavern owner in the 1860s, John Severn managed one achievement that influences the lives of Torontonians to this day. In 1875, acting as reeve of Yorkville, Severn was the guiding hand in obtaining drinking water for the town.

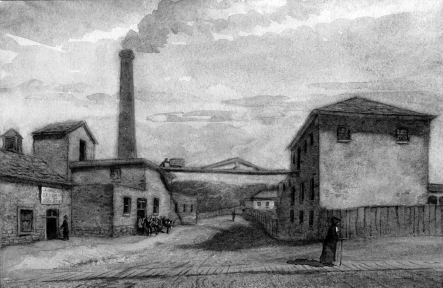

This view of the Severn Brewery is from Yonge Street. The inclusion of a third-storey platform, complete with railcar to transport goods between the malt house and brewery, would have meant a real savings on time, although quite slippery in winter. Toronto Public Library.

Although many options were considered, the creation of the Yorkville Waterworks was so clearly his responsibility that a banquet was thrown in his honour. It cannot be said to have been a purely selfless act of public service, as it allowed the creation of a fire brigade and made it possible for the brewery to stop using spring water piped in from Summerhill. However, the infrastructure that Severn created to service Yorkville still makes up the bones of today’s system thanks to improvements carried out in 1910.

In Severn’s final years, there is an episode that highlights a reason that the brewery may have ceased to operate. Yorkville, having had significant Methodist influence in its foundation and growth, was faced with a decision on the Dunkin Act in 1876. A petition of local ratepayers was deemed insufficiently signed to effect the restriction of liquor to four locations within the town. Local option temperance failed, and it is difficult to see how there could have been any other result with one of Toronto’s most prominent brewers chairing the committee.

George Severn would inherit the brewery in a rapidly changing Yorkville that could no longer tolerate breweries, slaughterhouses or brickworks amongst its residences. It was this mood in a growing population (five thousand in 1881) that viewed the neighbourhood as a residential suburb rather than an independent village that led to drawn-out legal battles over the sewage the brewery created in the 1880s. Its eventual closure happened within three years of the annexation of Yorkville. The Globe had forecast this eventuality in 1852 at the incorporation of the village: “It will soon come to be a subject of discussion whether Yorkville ought not to be annexed to Toronto. It is not to be expected that the city will remain ‘cabin’d, cribb’d, confined’ within its present narrow limits for any great length of time; it will soon grow too large for its garments and a good slice of the township of York will be necessary that it may have ample room and verge enough for its gambols.”

This lithograph of Severn’s Brewery seems to be a view from the northeast of the facility. Note the residential portion of the building in the right foreground with its gallery-style balconies, almost reminiscent of an English coaching inn. Toronto Public Library.

The brewery property on Severn Street is occupied now by the Studio Building, which housed many of the Group of Seven painters during the early portions of their careers. Tom Thomson painted in a shack on the property, and it was in that shack that his masterpiece The West Wind was found upon his death in 1917. The building was favoured by artists for its north-facing windows and for its view of the valley receding north across Yonge Street and the foliage on the opposite slope of the ravine. Severn appreciated as much when he built the brewery. As Henry Scadding related, “There is a picturesque irregularity about the outlines of Mr. Severn’s brewery. The projecting galleries round the domestic portion of the building pleasantly indicate that the adjacent scenery is not unappreciated: nay, possibly enjoyed on many a tranquil autumn evening.”