Chapter 13

COSGRAVE BREWERY, 1844–1960S

The West Toronto Brewery was located on the southwest of Queen and Niagara Streets, directly across the ravine from John Farr’s Brewery and across the street from Trinity College. It was built in 1844 and was originally a business venture on the part of Thomas Baines. Baines was not formally trained as a brewer but may have picked it up from a colleague in his early professional life. He worked with Peter Robinson as a land and immigrant agent on the settlement of the Irish in Peterborough. Robinson was a relatively well-known brewer in Newmarket in the 1820s and ’30s.

Baines came to Canada in 1821, and brewing was not his first career. Even while he owned the brewery, he had other employment. He was deputy auditor general for Upper Canada before being put in charge of the sale of the Clergy Reserves. He would eventually find himself the Crown’s land agent for the Home District, which stretched from Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe. It is unlikely that Baines was personally involved with the running of the brewery, leaving that to his partner, Isaac Thompson.

Baines resigned his commission as land agent in 1855 following the realization that he had created the single largest default in Upper Canada’s short history. The ruling in 1859 found that £30,000 of the public’s money had been either embezzled or lost through misadventure. The verdict handed down was that all Baines’s property was to be seized. Fortunately, Baines had parted ways with Isaac Thompson in 1857 through a dissolution of their partnership.

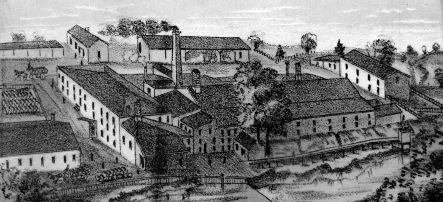

This is an image of the Cosgrave West Toronto Brewery as seen from approximately the roof of the Farr Brewery across the ravine. Note the impressive width of Garrison Creek in the foreground, dating the sketch to the 1870s. From Timperlake’s Illustrated Toronto.

Thompson would have been the brewer on a day-to-day basis anyway. Even in the dissolution notice, there were hints that he was the one running the sales side of the business. He was selling beer in partnership with his brother, Charles, through a series of grocery stores and the East India House. Thompson spent most of the time that he owned the brewery, between 1857 and 1863, making upgrades that he felt were needed.

In 1863, the West Toronto Brewery was taken over by the partnership of Charles Sproatt and Patrick Cosgrave. Of all the brewers in Toronto, Patrick Cosgrave had the longest road to independence. His first brewery had been located on the Credit River in Etobicoke and had existed as a partnership with John Moss. The brewery had plenty of access to water and barley, but the majority of the beer-drinking population lived in Toronto. For an ambitious brewer, the location was a nonstarter. Moss must have felt the same way, as he ended up a scant hundred meters away running John Farr’s brewery in the 1860s.

Ambition was a key factor in Patrick Cosgrave’s early years in Toronto. He had, at least according to his obituary, arrived in Toronto with scarcely a dollar in his pocket. He had eventually found himself as a salesman for the Aldwell-leased Victoria Brewery before partnering with Eugene O’Keefe to lease the property and commence brewing for himself. The partnership, beginning in 1861, lasted only two years but resulted in a threefold return of the initial investment, allowing Cosgrave some freedom to find his own venture. His partnership with Sproatt would last about four years, until Sproatt moved to the Spadina Brewery.

Cosgrave, throughout its existence, experienced some real problems with branding. It developed in several different directions, but one of the longest lived was the elk and horseshoe combination. Molson Archive.

The combination of the diamond shape and corkscrew is an early development for the Cosgrave branding. The Pale XXX Ale name would be abandoned by the time India pale ale became the more popular designation in the 1890s. Molson Archive.

From the beginning, the Cosgrave Brewery had been a family affair. Patrick Cosgrave employed both of his sons, John and Lawrence, in the running of the brewery and his nephew, James, in the management and bookkeeping side of the enterprise. Between 1867 and 1879, the brewery was built up considerably, developing the capacity to malt seventy thousand bushels per year and brew sixty thousand barrels, split between two separate facilities. Cosgrave had won medals for its pale ale in the 1870s at two consecutive world’s fairs in Philadelphia and Paris and twenty-five thousand barrels was set aside for its deservedly popular ale. Thirty-five thousand barrels of capacity was designated for lager, and by 1879, Cosgrave had taken to producing a Vienna lager.

The same year, a fire raged through the original brewery building, completely destroying it. All that was left were the lager brewery and the malt house. There had been plans in place to replace the ale brewery with a more modern structure in any event, but this development ensured that the new building to be constructed would be fireproof. The choice had to be made whether in the short term to continue to produce ale or lager in the remaining building. It was a difficult choice for the reason that the Toronto market was suddenly flooded with lager thanks to Lothar Reinhardt at the Walz brewery and Eugene O’Keefe’s new facility. A meeting of the victuallers association established a maximum price that members would be willing to pay for lager at wholesale; this price would have constituted a loss in revenue at a time when the brewery was attempting to expand. Cosgrave’s would abandon lager for the time being, settling on the decision to become the sole licensed importers of Valentin Blatz’s lager from Milwaukee in 1889.

Patrick Cosgrave passed away in 1881 at the age of sixty-four. His sons, John and Lawrence, would form a new corporation under the name the Cosgrave Brewing and Malting Company. John Cosgrave was mostly interested in commercial expansion into the Northwest Territories and sat on the Toronto Board of Trade. Lawrence was more suited to the business of brewing, and the 1882 decision to focus on the extra stout and India pale ale was his. His rationale was that “[n]ecessity will no longer exist for importing foreign Ales and Porter, as our patrons CAN DEPEND upon us furnishing an article equal to Bass or Guinness at a much less cost. Warranted PURE and healthful. FREE FROM ALL DELETERIOUS SUBSTANCES.”

The trademark employed on this badge-shaped label for Cosgrave’s Extra Stout is a bisected triangle, perhaps emulating the legendary Bass mark. Molson Archive.

Lawrence Cosgrave was a formidable athlete (for a time the Royal Canadian Yacht Club had a Cosgrave Cup), and unlike many of the brewers, who used the recommendation of doctors on their product labelling, he had actually made a personal study of nutrition and believed in the power of beer to promote health in moderation. From the Daily Mail and Empire in 1898:

I have always looked upon malt liquors as a food product, and those who object to their use have not a proper understanding of this article. These individuals undoubtedly daily use milk, but consider malt liquors injurious. Malt liquors, brewed in a right manner, and of proper material, are a far more healthy and tissue-making drink than milk…I am endorsed by some of the greatest physicians in the world in my opinion that the ladies would enjoy much better health in this country if they used good beer in the same way as they use milk.

Under his vigorous management, the size of the brewery that had burnt in 1878 was quadrupled, and by the turn of the century, the overall capacity had been expanded to 100,000 barrels. Lawrence Cosgrave had an important managerial skill: the ability to hire good people and get out of their way. The brewer was Charles Hodgson, who had worked his way up from a role as an apprentice in 1882. The maltster was Charles Thomas, who had acquired some thirty-five years of experience in malt houses around Toronto, including Copland’s. James Cosgrave, Lawrence’s cousin, acted as secretary and treasurer and began quietly purchasing interests in Toronto’s licensed hotels as the Scott Act came into play in the 1890s.

The brewery’s other great strength was its bottling facility. While many breweries in the Toronto area focused on licensee sales, the Cosgrave Brewery had a world-class bottling facility and exported its beer to destinations as remote as Australia, South Africa and the West Indies. Accounts from the period agree on the sheer volume being sold in this method, the brewery keeping 120,000 bottles on hand at any given time. The bottling room was separate from the racking cellar by three hundred feet and was supplied by means of a specialized pump that John and Lawrence Cosgrave had invented in 1879. The bottle filler could manage 10 bottles simultaneously. The brewery could package 7,200 bottles per day. The supply of beer came from the capacious 150,000-gallon cellars.

Under Lawrence Cosgrave, the brewery performed so well that when the malt house was struck by a fire begun in the malt kiln in 1904, wiping out the cooling equipment, fermenters and mill, he simply purchased the languishing Toronto Brewing and Malting Company. The Cosgraves would own the facility until the 1920s, operating it during prohibition as the Toronto Vinegar Company.

Cosgrave’s extra stout was, like many stouts of the day, endorsed by medical specialists. The combination in branding in use at the time is a bull moose and horseshoe. It is a better pub name than a trademark. Molson Archive.

By the time it became the Cosgrave Export Brewery Company Limited, the mascot for the Cosgrave concern had switched to a rather stunned-looking tiger. The brewery produced a pale ale, a Porter and a blend of those two products creatively called Half and Half. Molson Archive.

The third generation of the family running the brewery shared their father’s sporting outlook on life. James F. Cosgrave would be the face of the business, joining the company in 1906 and becoming president and general manager in 1910. James was considered at one time to be the finest sculler in his weight class in Canada. His brother, Lawrence Moore Cosgrave, worked briefly at the brewery as teenager but did not enter the family business significantly, embarking on a military career instead. He was a graduate of the Royal Military College in Kingston and won the Distinguished Service Order twice during the First World War. He was much publicized for that and for successfully proposing marriage to his childhood sweetheart from his position in the trenches. He was the Canadian representative for the signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender at the end of the Second World War.

The Cosgrave Export Brewery was incorporated in 1922 and did a modest trade in the 2.5 percent and 4.4 percent proof spirit beer that was allowed to the public prior to 1927, but that’s not to suggest that they were not also doing a solid business in regular-strength beers. Shipments of 150 cases were known to wash up from time to time on the public beach outside Rochester, New York. People were frequently fined for driving away from the brewery with cases of over-strength beer. Many hotels around Toronto were shocked to learn that instead of the low-alcohol temperance beer, they were stocking regular-strength beer. Despite their protestations of non-complicity, they seemed to serve the stronger stuff to people requesting “good beer.”

The Cosgrave Export Brewery was frequently fined for its transgressions, but realistically there was no punitive amount that would dissuade it. In April 1927, it came out that James F. Cosgrave had been using a very basic bureaucratic loophole to supply Toronto hotels with strong beer for just over four years. Toronto hotels were disallowed from ordering any product over 4.4 percent proof spirits. Orders for export were a different story.

Orders received from the United States were technically legal, although under the Volstead Act it would have been quite difficult to get any beer across the border. The solution was that Toronto hotels would phone a proxy in the United States who would place the order. A truck would arrive at the brewery and take the beer away. Because Cosgrave did not own the trucks, he pleaded ignorance as to their destinations. Payment was also accepted through a proxy. When asked if he was surprised that the B-13 customs forms were never returned to the brewery, he stated, “We presumed they would come back in time.” Since they had paid the taxes, no significant punishment was rendered despite their reputation as the “most flagrant violators of the Ontario Temperance Act.”

Cosgrave was the only brewer in Toronto to produce a Scotch ale after prohibition. The taste had switched dramatically from ale to lager as a result of American influence and several decades of temperance movements. Molson Archive.

In 1934, E.P. Taylor’s Canadian Breweries bought out the Cosgrave-owned West Toronto Brewery and kept James F. Cosgrave on board as his vice-president, leaving him in charge of the plant. There may have been a grudging respect for the hard-nosed approach that James had used in the latter days of the Ontario Temperance Act. It may have been his keen interest in horse racing, which Taylor shared. Cosgrave retired in 1939 to start up his own very successful racing team. The Cosgrave Brewery would survive until the 1960s under E.P. Taylor’s watchful eye before being demolished as redundant to his empire. It was briefly replaced by a location of Brewer’s Retail in the 1970s.