Chapter 14

O’KEEFE BREWERY, 1840–1960S

There’s very little known about the early days of the Victoria Brewery. It was located at the southwest corner of Victoria and Gould, a scant block north of what is now Dundas Square. It is claimed that the brewery was established in 1840 at 30 Richmond Street, but if it was, it made such little impact that there is no record of it in the city directories of the time. It was probably moved to the Victoria and Gould location by Charles Hannath and George Hart in 1849. While Hannath was a brewer by trade, he did not retain control of the business for very long. In the early 1850s, the Aldwell brothers had the lease on the property.

The brewery was not particularly large or well appointed. There were drainage problems significant enough that the Aldwell brothers moved to a new facility of their own design at the first possibility. They had been leasing from Hannath and Hart, who now needed to find new tenants. It’s possible that the brewery would have languished, but the partnership of George Hawke, Patrick Cosgrave and Eugene O’Keefe was waiting in the wings. It was a unique partnership in largely Protestant Toronto for the reason that all of the members were Irish Roman Catholics. They took over the Victoria Brewery in 1861.

It can’t be claimed that they took over the brewery in working order. The first advertisements in the newspaper were not for the sale of beer but rather tenders for basic equipment: a boiler, an engine and stabling large enough for three horses. With all of these problems, the brewery was producing something like eight thousand barrels of beer per year. Things went so badly that Cosgrave left the partnership in April 1863, and it was renamed O’Keefe and Company. It’s hard to blame him. At the time, it must not have seemed worth the bother.

This label for O’Keefe’s India Pale dates from before 1891 and gives some indication that the product was bottle conditioned for carbonation. The instructions suggest that you let the bottle stand and then pour without shaking. Good advice. Molson Archive.

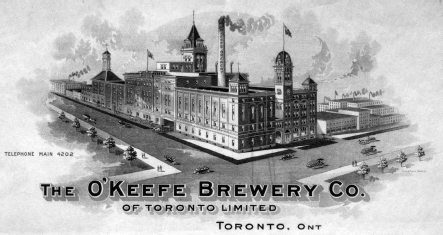

The O’Keefe Brewery Company’s letterhead gives a sense of the scale of the O’Keefe Brewery. The view here is from the northeast corner of Victoria and Gould Streets. It is now the Ryerson University Campus Store. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

In early 1864, it became apparent that the brewery’s water supply was going to be cut off. The water supply depended in part on the Yorkville Reservoir, which was losing the city one thousand pounds per year and whose contract was unlikely to be renewed. Faced with calamity, O’Keefe was pragmatic, a trait that would persist throughout his career. While clearly engaging in self-preservation (breweries require staggering amounts of water), his letter to the Globe took a public-spirited approach:

It is a matter that calls for the immediate action of the public. As no intimation has before been given, we beg to remark that a large portion of the city will soon be deprived of one of the greatest necessities of life, and subject to great inconvenience and peril—first, by the deprivation of water, and the consequent great increase in the rates of insurance; and secondly, by the great chances of fires that will inevitably occur, should such a contingency as we have noted take place.

While this could easily have been seen as a cynical manipulation, O’Keefe’s character over the length of his career makes it clear that this is not the case. While Eugene O’Keefe did not compromise the success of his business or his personal success, he realized that he was a part of a larger society. Whether it had to do with his deeply held religious beliefs, a sense of civic-mindedness or even basic give-and-take pragmatism, he would typically attempt to do his best for the society around him. He was both well meaning and calculating, an admirable combination.

As a case in point, take the donation on June 6, 1866, of two hundred gallons of ale to the garrison at Fort Erie. Four days prior, Fort Erie had found itself briefly occupied during the Fenian Raids. The majority of the Fenians had surrendered to the Americans in New York State. The gesture accomplished a number of things. At its most basic level, it was a gallant show of patriotism. It additionally separated in the minds of the public O’Keefe (himself a moderate Irish nationalist) from the extremist Fenians. Further, it promoted the brewery. It was beneficial for all parties involved.

Under O’Keefe and Hawke, the brewery expanded rapidly. By 1868, they had been kitted out with an entirely new set of machinery, obviously a necessity given the state of the brewery in 1863. Not only had they purchased a twenty-five-horsepower engine and boiler, but they were also contemplating an expansion for increased fermentation, cellarage and cooling. The expansion would allow them two thousand gallons of production per day, or about twenty-three thousand barrels per year. Most impressive is the variety of hops being used. In addition to locally sourced hops from Ontario, O’Keefe and Company were using Bavarian, Belgian, Mid Kent, Worcester and Wisconda hops.

The O’Keefe Brewery relabeled all of its beers using the term “Imperial” at some point after the brewery was expanded in the late 1870s. There’s no indication that they were a great deal stronger than they had been previously. Molson Archive.

After the renovation, the brewery contained five fermenting vats of 4,000 gallons each and “an immense copper refrigerator for summer use,” which was the first of its kind in the province. The dual three-floor malt houses were each thirty feet wide. One was one hundred feet long and the other sixty. The larger of the malt houses had a kiln that was eight hundred feet square. It was able to malt forty thousand bushels a year for its own purposes and sold the excess only when it was convenient. The icehouse had a capacity of 250 tons, which was enough to keep the 180,000-gallon vault beneath the brewery at a reasonable storage temperature during the summer. By this point in 1871, it was already exporting its stock ale to New York and Chicago, despite a nearly 80 percent duty on imports. This may have been the result of its policy of sending free samples of the product to hoteliers and bottlers throughout the Dominion and the United States. It had tripled its business in eight years.

It may seem miraculous that a small brewery with severe problems should have been able to accomplish that amount. John Aldwell, the previous tenant of the brewery, did not lack for ambition either. What he did not have was a close association with the Toronto Savings Bank. O’Keefe had been a clerk at the bank prior to becoming a brewer and remained affiliated at the highest levels throughout his career. He would continue to expand the brewery indefinitely for the reason that he had unfettered access to the capital to do so.

In 1879, O’Keefe became the second brewer in Toronto to produce lager. The introduction was as much about moving the product as it was about improving the society. The following somewhat contradictory paragraphs from the same full-page advertisement heralding the product launch display O’Keefe’s combined motivations:

The Lager and “Pilsener” brewed by Messrs. O’Keefe and Co. are pronounced equal to the best on the continent of Europe. The hops used in those beers are from Nuremburg, Bavaria, and are imported directly by the firm. The malt is prepared specially at their malt houses by a process different from that of any other in this country, and the article produced my justly be styled the “CHAMPAGNE OF MALT!”

Messrs. O’Keefe and Co. contend that the benefits accruing to the country by the introduction of first class malt beverages cannot be over-estimated and will tend more to the interests of TEMPERANCE than all the legal enactments and repressive measures that any Government may introduce…Coming nearer to home, we find in the United States of America a PEACEFUL REVOLUTION going on in the drinking habits of the people. This is particularly noticeable in the large centres, such as New York, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Milwaukee, Chicago and Buffalo. In the latter city the change in the last ten years is truly marvellous, a High Church dignitary of that place stating “that the next greatest blessing there after the advent of religion was the introduction of Lager Beer, as it completely weaned the people, particularly the working classes, from the use of stronger beverages.”

O’Keefe was not a believer in the prohibition of alcohol, but he was a proponent of temperance in his way. It may seem ludicrous, but his position is highly congruent. While he was certainly very wealthy, an Irish Roman Catholic in Toronto was very much a minority. The working classes mentioned were O’Keefe’s people: first-and second-generation Irish immigrants who were ruining themselves on cheap whiskey. O’Keefe knew that prohibition would only create illicit markets and additional suffering. If people were going to drink, then lessening the sin of doing so was a noble calling.

Some people naturally assumed that this was an act, and Eugene O’Keefe had a sense of humour about it. While being cross-examined on the issue of prohibition in 1893, he was asked whether it would have any impact on the value of his property. O’Keefe replied, “Why bless your soul, it would be ruinous.” Asked whether it could be used for a different purpose, he replied, “I suppose it might be used for a shoe factory or Salvation Army barracks.” Later in the inquiry, he testified that he thought that “the solution of the temperance question was to be found in the consumption of lager beer and light non-intoxicating liquors. If you could see a million people without the colour of liquor upon them it would be a pleasant state of affairs, and that is what I saw in Chicago where Lager Beer is the great drink.” He admitted, however, that he was “not in the brewing business for the sake of temperance.”

His testimony was important to the issue. By 1893, he had one of the largest breweries in Toronto in the wake of yet another expansion, producing nearly forty-five thousand barrels of beer annually. A series of illustrated double-page features in the Globe in 1895 exposed the interior workings of the brewery to citizens in the wake of yet further expansion. Rather than a single brew house, the O’Keefe brewery featured two of identical size capable of two 3,500-gallon brews daily or approximately five hundred barrels of beer daily. The stock cellars were expanded to include a second location—an entire block of Dalhousie Street, which also housed stables. The main facility was cooled by a fifty-ton De La Vergne refrigeration machine, which was “only permitted to run at their minimum speed. If they were run to their full capacity the whole block would be frozen solid.” The article concludes with the open invitation to the public to tour the brewery and see how its ale and lager are made. It was a policy of real transparency and comparatively unusual at the time.

By 1911, the entire structure had been replaced by a new facility capable of producing 500,000 barrels per year or, to put it in perspective, approximately thirty-five gallons for every citizen of Toronto. The same year, he began to withdraw from the brewing business on the occasion of the untimely death of his son, Eugene Bailey O’Keefe. A slowdown on O’Keefe’s part was inevitable. He was over eighty. He remained to the end of his brewing career a proponent of temperance rather than prohibition and was quoted as saying in 1912, “The prohibition of the bar is a preposterous and infamous policy. You can’t make men sober by act of Parliament.” History would prove him correct.

O’Keefe would use the wealth that he had generated from his involvement with the brewery and the Home Bank to improve the society around him. He would not only build churches to serve the community but also purchase and donate existing churches to new immigrant communities in the city. He had significant influence with the St. Vincent de Paul Society and helped establish Toronto’s first low-income housing. For his consistent dedication to the betterment of society, he was made a Papal Chamberlain in 1909.

O’Keefe’s death in 1913 was marked by a funeral procession of the cadets from De La Salle College and two hundred brewery employees. Three thousand people made up the congregation at his Requiem at St. Michael’s Cathedral. Pope Pius X had sent him a blessing on his deathbed. Archbishop McNeil summed up the spirit of Eugene O’Keefe’s attitude thusly:

O’Keefe’s Special Extra Hop Ale was released after prohibition. The Latin motto translates to “To the brave and faithful, nothing is impossible.” By this time, the brewery had already been purchased by E.P. Taylor, rendering that motto slightly less relevant. Molson Archive.

There was a good deal of benevolence practised in the world today, but in what spirit was it done? Was there not a sharp dividing line between those things that were done for men alone and those who had God in view? He need not ask on what side their dead friend was placed. He commended the example of the departed man to other well-to-do men and said that if wealthy men would remember they had a social as well as an individual function, the labour problems of the world would soon be solved.

O’Keefe’s Extra Old Stock Ale purports to contain more than 2.5 percent proof spirits. That would be slightly less than 1.5 percent alcohol by volume. It’s easy to see why breweries suffered in the wake of prohibition. Molson Archive.

O’Keefe’s Old York Ale preys on the feeling of nostalgia generated for ales in a post-prohibition period, where lager was already becoming king. People fudged dates in marketing even in the 1930s. The O’Keefe Brewery wasn’t established until 1863. Molson Archive.

His greatest philanthropic act would be completed posthumously. The construction of St. Augustine’s Seminary in Scarborough cost $500,000. O’Keefe was typically modest about it even in the planning stages, declining to be interviewed about his donation or the construction.

The brewery passed into the hands of a group of Toronto businessmen, none of whom could match O’Keefe’s business acumen. In comparison to O’Keefe, some of the behaviour they exhibited was downright inadvisable. Sir Henry Mill Pellatt built Casa Loma, which proved to be incredibly expensive to build (totalling seven times the amount O’Keefe’s seminary cost) and nearly impossible to maintain. Charles Millar was famous for his will in which he bequeathed one share of the O’Keefe company to every Protestant minister in Toronto, essentially using the hard work of a man who had struggled to better society to make a perverse point about human nature.

The O’Keefe Brewery, because of the sheer volume that it produced, was one of the cornerstones of E.P. Taylor’s Canadian Breweries. The brewery had survived prohibition by making various flavours of soda. While it was not one of the initial purchases made in 1930, the production volume allowed Taylor to streamline his empire, shutting down redundant breweries around the province. By the 1960s, the production had increased to 750,000 barrels. Production was eventually transferred to a new facility near Pearson Airport, which is still in operation under Molson Coors. The O’Keefe Brewery was demolished and the land sold to Ryerson University. O’Keefe’s house still stands one block east of Victoria and Gould and has been converted to student housing.