Chapter 15

TORONTO BREWING AND MALTING COMPANY, 1859–1967

The William Street Brewery is difficult to picture because both the brewery and the street it was named after no longer exist. While the location of the brewery never changed (breweries don’t just get up and walk away), the street names in the area changed with alarming regularity. Before 1860, Simcoe Street above Queen was called William Street. The brewery was on the block at the northwest corner of William and Anderson. Eventually, William Street became Simcoe Street, and Anderson was folded into Dundas Street. In point of fact, the William Street Brewery was so large that it causes the short jogs on Dundas Street in either direction.

It’s not surprising that it was built to a high standard. It was the product of profound dissatisfaction with an older brewery. John Armstrong Aldwell and his brother, Thomas, had become the proprietors of the Victoria Brewery at the corner of Victoria and Gould at some point in the early 1850s. While other brewers would own it eventually, the problems that the Aldwell brothers experienced with it suggest that the original brewers, Charles Hannath and George Hart, were right to sell out when they did. In the 1850s, the city infrastructure north of Queen Street was not up to much. There might not have been running water, and sewers were certainly not widely available. When you consider that Victoria and Gould is just a block from the main thoroughfare of Yonge Street, it becomes obvious that growth had outstripped public infrastructure.

John Aldwell was an ambitious man, and it’s likely that he was attempting to produce just as much beer as was possible out of the Victoria Brewery. Large production in a brewery means that there will be an even larger amount of waste liquid produced. In this case, there was no adequate drainage for the facility, and the wastewater simply flowed into the ravine on the next property over. The difficulty was that everyone in the neighbourhood was using that ravine for their drainage. It was a risk to the public health and a real eyesore.

Called in front of the court to settle the matter, it became clear that there was no plan for improvements in the neighbourhood. The box drain that Aldwell had installed to solve the problem had been removed by the board of health, which insisted that he pay double the going rate for the privilege of using the city’s sewers. The brewery’s business was being held hostage by poor infrastructure. Aldwell would either have to pay an exorbitant amount for the use of the city sewers or continue to pay increasingly large fines. Either way, it must have been frustration enough for him to decide to offload the property in 1859.

The solution to the problem was comparatively brilliant. In 1859, there were not state-of-the-art brewing facilities in Toronto. The majority of the operations that existed had been hand built by first generation settlers, and while they were of a size, they made do with brewing techniques and technology that existed in the 1820s. While the initial buildings were being constructed on William Street, Aldwell toured England to view the large industrial breweries that began to fill the landscape of the Victorian period. According to the Globe on July 29, 1859: “It is to be erected a little west of the College Avenue, facing William Street, and will be three storeys in height, 118 feet long by 93 feet broad, with a cellar 15 feet deep. The front will be of white brick, the remainder of the building red…steam elevators will be erected, and that provision for brewing from eighty to one hundred thousand gallons of ale and porter per month will be made. Probable cost $36,000.”

The brewery would have been massive. At maximum capacity, it would be able to produce the equivalent of just under a barrel of ale for every citizen of Toronto. It’s unsurprising that flooding the market in this way caused some controversy.

Temperance advocates had begun to take notice of the expansion of the brewing and distilling industries in Toronto. J.J.E. Linton made note of the expanded trade in the supporting notes to his proposed bill to Malcolm Cameron, MPP, in 1860. He quotes first the Globe from the year the brewery was completed as saying, “A very extensive brewery has been erected during the year by Mr. Aldwell…which will be one of the most complete establishments of the kind in the province. He has spared no money in introducing all the latest improvements, and his enterprise entitles him to success.”

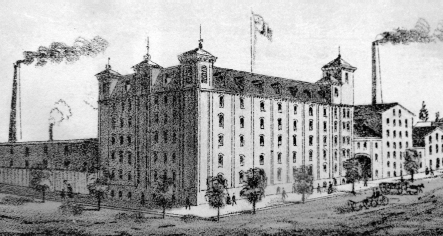

The Toronto Brewing and Malting Company, constructed by John Aldwell, was certainly the most attractive of Toronto’s Victorian breweries. The sense of symmetry and attention to design is immediately apparent. It kept the bear out back. From Timperlake’s Illustrated Toronto.

Linton’s take on the matter differed substantially from the paper of record: “We ask this question: What good morally, religiously and socially, to Toronto, does the above ‘Liquor Manufacture,’ in its city, accomplish?”

Two decades earlier, some of the most accomplished proponents of temperance in Toronto had been brewers. They had understood that it was possible to divert the proceeds of vice to assist in the betterment of their society—that there could be harmony. It was, perhaps, a sign of the changing times in a city whose population was expanding rapidly that Linton could not see the potential value of the industry. The early settlers had been able to exert their will on an untamed landscape and create a society. Creation and maintenance require different approaches.

Aldwell might have fit more easily into the previous generation of settlers, according to his son Thomas Theobald Aldwell’s memoirs: “My father had started making beer in a tub and when he died he had what at that time was the largest brewing and malting company in Canada. It comprised half a block on Simcoe Street. As I recall there were four stories in this concrete building. Father never took a drink. He would put the beer in his mouth to get the taste and then spit it out without swallowing any of it.”

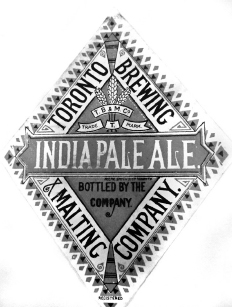

This label for the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company’s XX Porter illustrates both the reach of the brewery, having been bottled in Montreal, and the system of gradation used ales and porters in the Victorian period. The additional X means it’s a stronger beverage. Molson Archive.

While he may not have swallowed any beer, he certainly made more of it than anyone else in Toronto—nearly twice as much as the next leading brewery. That was not the limit of the plan for Aldwell’s William Street Brewery. The brewery was renovated in 1863. In 1866, it was vastly expanded. The main building was raised two and half storeys, which would likely have made it the tallest building north of Queen Street. An elevator was installed for moving grain through the building. The wort cooler could manage fifty barrels per hour. The malt kilns and the offices were all gas lit. It was a thoroughly modern concern covering an acre of ground.

In 1868, it became the second-largest malt house in North America. While the stock quotes in the Globe for the time reference breweries dealing in bushels of malt purchased at market, it refers to Aldwell’s purchases for his brewery by railcar. The gargantuan malt house was described in the newspaper thusly:

The frontage of this new addition, on William Street, is 125 feet and the frontage on Anderson Street nearly 86 feet. The height from the ground to the top of the roof is about 60 feet, divided into six stories with an underground cellar way under about one half of the structure. At each corner of the new building are towers projecting up to a height of about 10 feet further, and capped with handsomely finished gilt vanes. In the architectural design, the modern French style predominates, and has been made to combine beauty with utility, as closely as they can be allied with permanency and strength…In every sense, the building is of the most substantial character, the supports on the different floors being of iron, while the steep roofs are slated.

Aldwell had significantly expanded his business, and he had done it with style. Not only that, but he had also worked in impressive technical detail. Rather than direct-fired kilns, the malting system had furnaces in the basement with chimneys used to direct heat to kilns on different floors of the building. Between the old and new buildings, Aldwell’s brewery had the capacity to malt 220,000 bushels per year. So massive was the enterprise that they constructed two grain elevators on the wharves downtown for incoming barley and outgoing malt. He was known to charter entire ships to sell his product in Chicago. His brewery remanded one-tenth of all the duty paid by the hundred plus breweries in Ontario.

This label from the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company suggests that there may have been a playing card motif in the 1890s rebrand. Note the spades running along the border of this ovular label. Molson Archive.

It’s unsurprising that Aldwell and his brewer, William Scott, were chosen as the scientific experts on new agricultural products. In later life, when George Brown had taken up farming at Bow Park, he experimented with a strain of barley called Chevallier, which he likely acquired during one of his trips to England. In Upper Canada, the majority of the barley in use was six-row, which is slightly higher in protein and slightly lower in starch. In December 1869, the two varieties were malted side by side. The Chevallier took slightly longer to germinate but resulted in improved yield and greater extract when compared to the varieties in current use. Had circumstances been slightly different, Ontario might well have switched to two-row barley in the 1870s.

Aldwell’s ambitions didn’t stop with the malt house. He had a plan to open a sugar refinery in addition to it. The minutes of city council’s discussion of the proposal reveal the staggering scale of the project. He had asked for twenty-five years’ worth of local tax exemption for a refinery that would require an outlay of $175,000 and employ 175 men—slightly more than 1 percent of the working population of the city at the time. It would have been the largest operation of its kind in Canada.

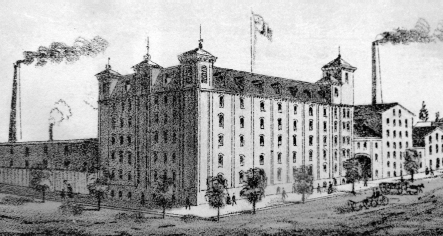

Not only did the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company have the second-largest malt house in North America (pictured in the foreground of its stationery), but its sales reach had also extended into Northern Ontario by 1876, giving it one of the country’s largest distribution networks. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

Unfortunately, Aldwell died at forty-seven in Ogdensburg, New York. It’s likely that he was returning from England or negotiating sales of his malt at the time, Ogdensburg being a prime rail connection. It was an unfortunate time for his passing, as the brewery’s ownership was in the middle of being restructured. Brooks Wright Gossage had been a partner in the business and had decided to part ways with the company. Thomas Aldwell, John’s brother, took the opportunity to get out of the business upon John’s death. Louisa Aldwell was left attempting to run one of the largest breweries in Ontario without any financial expertise or firsthand knowledge of the industry.

John Aldwell may have been a visionary, but without a plan in place for the eventuality of his death, the business would pass into the hands of others who lacked his ambition and entrepreneurial drive. The next year, the brewery was restructured as the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company. It would go through several changes of management, all of them somewhat less inclined to the task of running the brewery than its founder. While the day-to-day running of the business would remain in the hands of the brewers and maltsters, the management was fraught with petulant intrigue.

In 1881, J.N. Blake, the president of the company and primary shareholder, went on vacation to England. During his absence, the members of the board of directors made a number of shocking decisions. For one thing, they donated the brewery’s mascot, a black bear named Bruin, to the newly opened zoological gardens. For another, they decided to usurp Blake’s role as president of the company. The annual meeting was delayed without notice, causing Blake to miss it. The board, led by H.L. Hime, voted Hime in as president of the company.

Under Hime, the board’s position was that since the majority of the stock owned by Blake was held by banks as collateral for advances on the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company, he did not really own the stock. He merely represented it. Blake’s position was that since the annual meeting had been delayed, the decision to replace him was made at a special meeting and that the whole issue was highly irregular. The matter was eventually brought to the courts when Blake entered the brewery with ten specially deputized bailiffs and seized control of the management offices, bolting the doors. The act of locking the maltsters and brewers out of the offices was as literal as it was symbolic.

The presiding judge on the case refused to find in favour of any of the parties involved, suggesting that it was not a matter for the courts. The upshot of the dispute was that several of the board members and many of the employees of the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company left in order to take over Copland’s East Toronto Brewery. The management of the company had not merely failed to grow the business but had actually created additional competition.

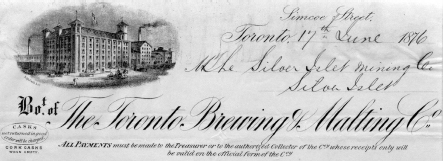

The diamond-shaped label of the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company came about through the launch of an individual brand called Diamond Ale in the late 1890s. While Diamond Ale did not survive as a brand, it changed the branding for the rest of the beers on offer. Molson Archive.

There is some evidence that the lack of a clear direction for the company persisted throughout the 1890s. The president of the company, Alexander Manning, was more interested in political life and his other business ventures. In 1885, Manning campaigned for a return to the mayoral office on his record as “the best mayor Toronto had ever had” but was ultimately defeated by William Howland because of Manning’s involvement with the brewery. In fact, a petition for a reduction in the number of licenses available within the city of Toronto was brought before him in December 1885. The results were entirely predictable considering the mayor’s business interests. The brewmaster would have been John S.G. Cornnell, who had closed both the Farr and Spadina breweries; Cornnell haunted Toronto’s late Victorian breweries like the grim spectre of death.

There is also a prescient example of marketing being as important to the brewery as the product. While they brewed stout, amber and India pale ales, they also briefly offered a Diamond Ale. It was quickly abandoned, but the labels employed for all of the brands took on a diamante shape as a recognizable trademark. At the turn of the century, all three of those beers would have routinely been between 6.5 percent and 7.0 percent alcohol. The low final gravity on all of the products would have rendered them very dry, although the stout would have been the sweetest.

There is little to report of the brewery through the first decades of the twentieth century. It carried on through Manning’s death and in spite of Cornnell’s track record. It was purchased and managed by the Cosgrave Brewery before prohibition, marking a brief period of stability. By the time of prohibition, it had become a vinegar factory. It was only in 1927 that it began to produce beer again. It had begun to produce a lager brand known as Liberty Beer, which failed to capture the imagination of the public. The rebrand of that beer to Canada Bud was a knowing emulation of the branding of Anheuser-Busch’s Budweiser brand. It proved so successful that it renamed the brewery in 1928 to Canada Bud from the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company.

When you look at the label that Canada Bud was using for its beer, you realize very quickly that Anheuser-Busch ought to have sued the brewery sooner, if anything. The owners must have been completely bereft of ideas. Molson Archive.

The company was sued almost immediately, and rightly so. By 1933, the lawsuit with Anheuser-Busch had forced a label change, causing the brewery to lose its most potent marketing weapon: duplicity. It would almost certainly have paid a larger settlement if prohibition in the United States had not prevented Anheuser-Busch from competing in the Canadian market for the previous decade. As it stood, it was forced to pay the princely sum of five dollars in damages.

The management of the Canada Bud brewery was extremely slippery. While it was profiting from the production of Canada Bud lager, it had reached the production capacity of the brewery. The manager, Charles Kiewel, was of the opinion that rather than expanding the existing facility, it would be more profitable to take over the City Club Brewery. The City Club Brewery occupied the space that had been Kormann’s on Richmond Street at Sherbourne. The president of Canada Bud, Duncan McLaren, set about acquiring the brewery for Canada Bud.

A significant problem with the merger of Canada Bud and City Club Breweries was that they produced beer for each other under the other’s label. Student Prince Lager is seemingly a tribute to Sigmund Romberg’s operetta of the same name, thus catching the lucrative beer-and-opera market. Molson Archive.

Canada Bud’s Special Bitter Ale was brewed and bottled for it by its subsidiary, City Club Breweries. One wonders how much difference there would have been between City Club’s Bristol Ale and this product. I suspect the label may have been the sole difference. Molson Archive.

Canada Bud Stout was produced at the City Club Brewery, which had housed Ignatius Kormann’s lager business. Why one would produce ale in a brewery purpose built for lager is a mystery. Post-prohibition brewers were mostly interested in getting volume out the door. Molson Archive.

The business practices involved were highly irregular. McLaren and Kiewel set about purchasing the brewery themselves, neglecting to use company money or to acquire the approval of Canada Bud’s shareholders. McLaren was attempting to sell the newly acquired City Club brewery to Canada Bud for $325,000. From the perspective of the shareholders, the difficulty was that McLaren stood to personally profit $167,335 on the transaction. After protracted meetings with angered shareholders and allegations of fraud in the courts, McLaren and Kiewel decided to transfer the property to Canada Bud at cost.

The difficulty was that by 1933, with twice the production that it had previously had access to, the brewery had lost its marketing gimmick. The Kormann facility, designed to produce lager, was producing stout and bitter. The Toronto Brewing and Malting facility, designed to produce ale, was producing lager. The management not only was untrustworthy but also had been shown to be actively working against the interest of the company. Canada Bud lasted about four years before being purchased by E.P. Taylor’s Canadian Breweries Limited. In 1944, Canada Bud was rebranded under the O’Keefe name, and the City Club brewery was closed.

Aldwell’s William Street Brewery stood for one hundred years at the northwest corner of Dundas and Simcoe before its closure in 1967. It was the only legacy of one of Toronto’s most determined entrepreneurs. Had John Aldwell lived beyond forty-seven, it is likely that the face of the brewing industry in Canada would be very different today. Sadly, the potential that he created was frittered away over decades by incompetent, disinterested or unscrupulous management. Of all of Toronto’s early brewers, Aldwell’s memory deserves better.