Chapter 16

THOMAS DAVIES AND THE DON BREWERY, 1846–1907

The Davies family emigrated from Ashton Upon Mersey, Cheshire, in about 1832. They were not initially brewers, but rather farmers. They settled three miles to the north of the town of York in the third Concession. Initially, the location where they settled did not have a name and acquired one only when John Davies became the area’s first postmaster in 1840. (Throughout the official records of the time, the name is given as both Davies and Davis.) Davisville was never as populous a village as Yorkville or Eglinton and consisted of only a few hundred people.

The three Davies brothers—John, Thomas and Nathaniel—had a farm on the east side of Yonge Street that stretched east as far as John and William Lea’s land. Rather than growing significant quantities of grain, the brothers specialized in breeding livestock. It was not until 1846 that Thomas and Nathaniel Davies opened their brewery on Yonge Street near what is now Balliol and named it, creatively, the Yonge Street Brewery. Very shortly after its founding, they added the Yonge Street Brewery Hotel.

The Yonge Street Brewery would have done a comparatively small trade, and it’s probably for this reason that Thomas and Nathaniel Davies dissolved their partnership in 1849. In 1853, Nathaniel sold off the majority of the livestock that had lived on the farm in order to focus his complete attention on brewing. The Davies farm was a popular spot for agricultural contests. The York Township Agricultural Society’s annual plowing match was held there in 1860. As a brewer, it was a brilliant method of letting potential customers work up a thirst. Nathaniel Davies would continue to run the Yonge Street Brewery until 1862, at which point the property was sold. At that time, it was capable of producing one hundred barrels per week, although it likely did not have the ability to produce ale year round.

Thomas Davies would focus his attention on a brewery that he was able to purchase at the intersection of Queen and River Streets, popularly known as the Don Bridge Brewery. It had been built by William and Robert Parks in 1844 but was more ably administrated by Davies, who had five separate pubs distributed through downtown Toronto acting as his agents within months of taking over in 1849.

The brewery continued in the thoroughly unremarkable way that some breweries do. It sat on the banks of the Don River and continued to produce ale through the 1850s and 1860s. Thomas Davies was engrossed in the creation of housing on lots that he had improved, and the brewery, while profitable, was more of a means to create additional wealth than anything else. It was not until Davies enlisted his eldest son, Thomas Jr., in 1868 and changed the name of the firm to Thomas Davies & Son that change began to take place. The bill of fare at the time consisted of cream ale, pale ale and Porter. Cream ale was something a novelty in Toronto at the time and would have been aimed at competing with the influx of lagers newly available from the United States. The capacity of the brewery was two thousand gallons per day, or about twenty-eight thousand barrels annually.

This version of Davies Cream Ale was likely a product of the first decade of the twentieth century. The inclusion of the maple leaf on the design tends to suggest that the cream ale is more representative of Canada than the Blue Ribbon Beer from the same period. Molson Archive.

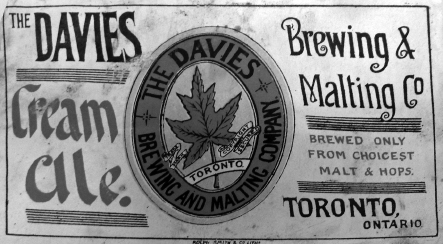

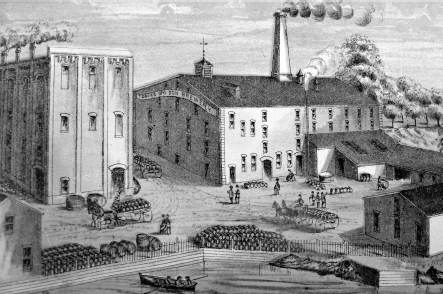

This image of the T. Davies and Bros. brewery captures a moment in history from the year before Robert T. Davies left to open the Dominion Brewery. By 1881, Thomas Davies was hard at work replacing this facility with a much larger one. The basic structure here dated from 1848. From Timperlake’s Illustrated Toronto.

Thomas Davies Jr. found himself, at the age of twenty-four, in charge of a brewery of not inconsiderable size. His uncle, Nathaniel, had passed away in 1866, and his father, Thomas Sr., passed away very shortly after making him a partner in the firm. The farm at Davisville had long since been sold off. It must have been a difficult transition, as having no choice in your livelihood but to operate a brewery might be daunting for a young man. There’s not a great deal to suggest that Thomas Davies was much of a brewer, even though he was highly educated. The relative inexperience showed through in the fact that the brewery was very nearly seized for excise discrepancies in 1871.

Fortunately, Thomas was not completely alone. His brother Joseph would become the managing director of the brewery and stay in that position indefinitely. By 1872, they were able to bring their younger brother, Robert, twenty-three years old at the time, into the fold and change the name of the brewery to Thomas Davies & Bro. Robert would have added a great deal of energy and focus to the arrangement.

By 1873, Thomas Davies found himself with enough free time to consider the widespread request that he run as a candidate for alderman in St. David’s Ward. He had finally found in political life an arena in which he excelled. In his first year as an alderman, he successfully led a movement to acquire John George Howard’s High Park for the city of Toronto, creating a large green space that exists to this day. It’s not without some irony that it is one of the few places in Toronto that remains free from sales of alcohol, in accordance with Howard’s wishes.

This early label from Thomas Davies’s brewery illustrates the development of branding in Toronto brewing. While it is almost certainly a stout or porter, Sable Ale is a far more persuasive name for those who are picking amongst a number of products. Molson Archive.

Davies was also instrumental in three other important pieces of business, none of which can be said to be entirely selfless for a brewer. He led the way in securing Riverdale Park for the city, a move that greatly benefited the citizens and at the same time managed to ensure that no breweries could be opened up on a large section of the Don River. In 1877, just before his temporary retirement from the position as alderman, Davies advocated as a member of the board of works for the takeover of the Furness Waterworks by the City of Toronto. This was generally beneficial to the city, as Furness’s infrastructure had proved inadequate on any number of occasions when buildings caught fire or even in simple day-to-day use. The waterworks were improved significantly. If you were a brewer, and you had foreknowledge of such a takeover by the city, you would be able to plan for it. The description of the new lager beer plant built by Davies & Bro. in 1877 reads as follows:

Great ingenuity has been displayed by the Messrs. Davies in fitting up and arranging the various departments that more business is done in proportion to the number of hands employed than in any other establishment of the kind in the Dominion. By using the city waterworks the water is forced to the highest level in the brewery, and thus they are enabled to do away with the time honoured pump. This is the first, or one of the first, breweries in Canada fitted up without a pump, and the arrangement of the tubs has been found to be so perfect that other brewers adopted the same style.

Davies & Bro. was one of the early adopters of lager brewing in Toronto, beating O’Keefe and Cosgrave by just under two years. The 1877 plant expansion came with the construction of Thomas Davies home at the northeast corner of Queen and River Streets. Called Rivervilla, it was a massive structure of a fanciful Italianate design. It would not be the last expansion for the brewery. An expansion of the original malt house and ale brewery structure increased brewing volume from 2,000 to 7,500 gallons per day. The malt house was capable of producing 250,000 bushels of malt per year.

This label for an export lager beer comes from the period during which the Davies Brewing and Malting Company was owned by a British consortium. Where exactly it was being exported to is a mystery, but it was warranted to keep in normal climates. Molson Archive.

It was not coincidence that Davies emerged from retirement as an alderman in 1881 and led a project to straighten, widen and deepen the Don River. The straightening of the river provide increased navigability for small steamboats, and the embankment that had run next to the Davies brewery was widened enough to create a rail line on it. For a brewery that had nearly quadrupled its capacity, this was a well-timed development.

In 1878, when Robert Davies left to found the Dominion Brewery just down the street, the brewery was renamed T. Davies & Company. In 1883, it became a joint stock company, and the name changed once again to the Davies Brewing and Malting Company. The prime difficulty in this era was the fact that there was very little consistent branding to be found amongst Davies’s products. By 1885, it had the sole use of the Blue Ribbon trademark in Canada but little in the way of promotion for it in periodicals of the day. It had replaced the promotion of its Pioneer Lager. The Gilt Edged Pale Ale was a longer lasting brand, making it all the way to the 1900. The cream ale may have been the longest lasting of all judging both by advertising mentions and current availability of labels to collectors. It also made a range of odd products in the 1880s like quinine ale and Porter, odd for a brewery that tended to focus on lighter-strength beers.

There was also some question as to the ongoing quality of the product. In the magazine Grip in 1885, this paragraph appears in a pro-temperance article:

The Davies Brewing Company was clearly connoting the production of a lager with a reference to the Pabst Brewing Company from Milwaukee. This simple label is likely from the first decade of the twentieth century, a vast decluttering of earlier designs. Molson Archive.

I see that Mr. Davies says the Blue Ribbon Beer that Cooper and Beckett—silly fellows—got drunk on, was brewed last June, was thick, muddy, etc., and not fit to drink. How was it, may I ask, that such stuff was on sale? Is that the way Mr. Davies serves his customers who bring him good money? And what has its bad quality in other respects to do with its alcoholic percentage? Mr. Davies says he can brew a beer entirely free from alcohol. Why, then, does he not do it and make a fortune?

One feels the goalposts shifting very slightly towards the end of the article, but the point is well made. As we have learned in a contemporary understanding in beer sales in Ontario, a product that frequently changes its packaging is not always to be trusted. Additionally, despite the heartfelt wishes of the temperance movement, it’s hard to make friends with de-alcoholized beer.

Thomas Davies’s involvement with the Don Brewery would continue until 1894. In 1891, a consortium of British investors would buy out his brewery, the Ontario Brewing and Malting Company and the Grant Spring Brewery in Hamilton. All told, the investment would be backed by $2,750,000. It was likely too high a price to pay, and in the long term, the properties were almost certain to depreciate without talented managers or the drive to expand.

The last hurrah for the Davies Brewery came in 1903. In 1902, there had been protracted discussions in the newspapers about the potential of using the building as an additional pork packing plant, but that was shouted down by citizens who did not want another such building in their backyards. City officials were quick to point out that the nearest dwelling was well over five hundred feet away, although their assurances proved futile. The English consortium that had purchased the Davies Brewery in 1891 had been attempting to unload the property for some time but had only been able to manage a bid of $15,000 at open auction—a figure that constituted less than half of the reserve bid. Fortunately, a man named John Dick purchased the brewery in 1903, retaining the Davies name.

This overelaborate label and compass rose is from the brief period in the 1890s when the Davies Brewing and Malting Company was owned by a British consortium. The label is topped by a crown and comes with a set of instructions for pouring. Molson Archive.

Another view of the T. Davies and Bros. brewery from 1877. Prior to the straightening of the Don River, it ran right next to the cooperage (foreground right) and stables (foreground left). Of the two large breweries, the one on the right was the ale brewery and malt house. From Timperlake’s Illustrated Toronto.

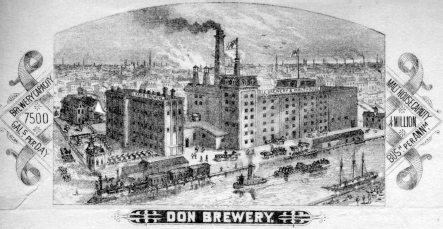

The Don Brewery, seen here on the company’s stationery, went through a prodigious expansion under the ownership of Thomas Davies Jr. It was certainly vast. This view is looking west at the brewery from across the Don River. The building on the left, labeled “Lager Brewery,” still stands today as condominiums. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

The Davies Brewery’s lager beer facility is the last surviving piece of that establishment. It has been turned into a quite attractive set of condominiums called the Malt House, but the building was never used for that purpose. Winston Neutel.

The Davies Brewery became the first in Toronto to unionize, joining the United Brewery Workers. For a period of nearly six weeks in 1904, the Davies Brewery was the only one operating at full capacity. That year, nearly seven hundred brewery workers in Toronto had walked off their jobs after demanding a 25 percent pay increase to $13.50 a week and a reduction from sixty-hour weeks. The brewery workers were so serious about the issue that they briefly allied with the temperance movement, threatening the very existence of their employers’ businesses.

The Davies Brewery was destroyed by a fire in 1907. The cause of the fire was given as spontaneous combustion. John Dick had insured the property for its entire value but was using a large portion of the outbuildings for another concern, the Ontario Storage Company. With no particular expertise in brewing or interest in reconstructing the plant, the Davies Brewery was officially shuttered in 1910. The southern building, which had housed the manufacture of lager, stands to this day as condominiums erroneously named the Malt House.

Thomas Davies passed away in 1916 just months after his brother Robert Davies. Just three years earlier, he had run for mayor against H.C. Hocken. Had he won that election, Thomas Davies would have been the man to approve the Bloor Viaduct. Although his career as a brewer lasted from 1868 to 1894, he spent the majority of his adult life as a public servant. Unlike his brother Robert, Thomas had used his gifts to help guide the city of Toronto through difficult periods of expansion and accomplish things that were difficult, even unpopular, but ultimately necessary and beneficial for the majority of its citizens. That these actions also assisted his business interests was a happy arrangement of circumstances.