Chapter 17

ROBERT DAVIES AND THE DOMINION BREWERY, 1878–1936

Key to understanding Robert Davies and the Dominion Brewery is the fact that Davies was intensely competitive. It probably resulted from his involvement in horse racing at an early age. In 1865, at sixteen years old, Robert Davies jockeyed a horse called Nora Criena in the Queen’s Plate. Due to a bizarre series of disqualifications on the basis of nationality and handicapping in the first and second heats, he actually won the third heat by a length and by all rights should have taken the Queen’s Plate. For reasons that are lost to history, the award that year went to the fourth-place finisher. For a competitive young man, coming second would simply not do. As an operating principle, Robert Davies was interested in being the best in the world.

Robert Davies was fuelled by this sense of competition even when it came to the family business. As the younger brother of Thomas Davies, Robert was an integral part of the firm at the Don Brewery under the name of Thomas Davies and Bro. He cannot have enjoyed playing second fiddle to his brother. Thomas was, by the time Robert joined the brewery, very accomplished politically. It was a vastly different sphere than the equestrian circles in which Robert spent his time.

In 1877, Robert Davies struck out on his own. Given all of the potential locations where he could have set up a brewery in Toronto, he chose a site less than two blocks from his elder brother’s operation, suggesting even there a friendly rivalry. The Dominion Brewery stands to this day on the north side of Queen Street at the corner of Sumach, largely unaltered from the way it was at its advent in 1878. Davies did nothing in half measures. The frontage on Queen Street took up half a city block at three hundred feet, and the handsome mansard roof lent the three-storey building a touch of class and a pleasing symmetry. Davies was completely aware of his own abilities as a brewer. Having come from the family brewery, he was well versed in brewing both ale and Porter, but he must have felt that lager was beyond him. He was not too proud to bring in German specialists for that part of the business. Additionally, the bottling was done at a separate location on Church Street through Davies’s agent, Thomas Defries.

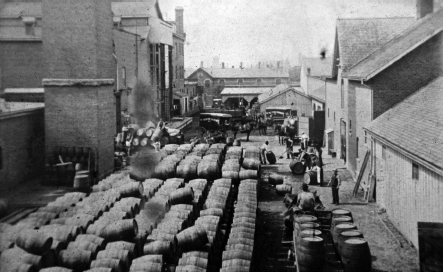

This image of the northern courtyard of the Dominion Brewery raises a good point about how breweries employed so many men in Toronto. In the days before forklifts, manpower would have been the only way to get the barrel on the dray. Hard, thirsty work. Sean Duranovich.

The brewery sprung up more or less fully formed, and the 1881 advertisements are different than those of other Toronto breweries of the day. In the majority of cases, the name of the brewery’s owner was used simply for the purposes of identification. It might appear once in a print advertisement. Robert Davies’s named appeared in the ad no fewer than five times in very large print. He wanted you to know that it was his beer.

The name of the brewery itself was an indication of his intention. The brewery would supply the entire Dominion of Canada. He made this known in the advertisement by running down the list of cities where it is available. This was so important to Robert Davies that he updated the same advertisement the next year to add Winnipeg. He had no doubt in the quality of his product. His attitude is summed up in the final sentence: “One trial is all that is necessary to enroll you amongst my numerous customers.”

This label for Robert Davies XXX Porter likely hails from before 1885, or else it would boast of its award from the New Orleans Exposition. Many brewers from the time used a beaver in their advertising, but the Dominion Brewery always used it in conjunction with a shield. Molson Archive.

The growth of the brewery was meteoric. Much of the early success that the Dominion Brewery experienced was due to the Scott Act, which passed in 1878 and allowed local option prohibition. It became impossible for Dominion to export full puncheons or hogsheads of beers to towns outside Toronto because it would be immediately obvious to inspectors what the contents might be. Instead, the beer was bottled and then shipped inside unmarked flour barrels at nearly five dozen bottles to the barrel. The Dominion Brewery, because it had adapted its business model to the circumstances that existed at its opening, would continue its rapid expansion.

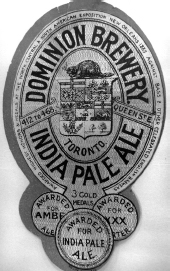

The brewery excelled in international competition. In 1885, the Dominion Brewery’s India pale ale, amber ale and XXX Porter would all be awarded medals at the North Central and South American Exposition in New Orleans. Winning awards for brewing beer was of approximately the same importance in 1885 as it is today—past performance is not an indicator of present quality. Robert Davies did not see it that way. As with the Queen’s Plate, which he had finally been awarded as an owner in 1871, Davies viewed the award as sacrosanct—absolute proof that he was the best in the world.

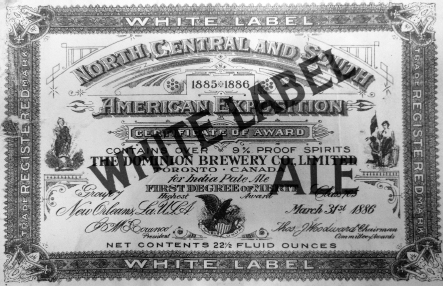

Some men would be content with a small amount of text around the edge of the label on the bottle. Some would choose, as Labatt’s had chosen, to simply display the medals tastefully on the label. Robert Davies was satisfied with that for a time. Eventually, he replaced the entirety of the label of his India pale ale with the certificate awarded to the beer in 1885. This was how his White Label Ale was created. Moreover, Davies would subsequently enter his beers in as many competitions as possible. Although it’s reasonable to hold some skepticism, there’s a real possibility that it might have been as good as the accolades suggest. White Label Ale would have been a 6.5 percent India pale ale made with Kent hops and likely in the style of Bass, although somewhat lighter.

This label for the Dominion Brewery’s India pale ale tells us something of Robert Davies’s character as a sportsman. Not only is he representing Canada with the beaver and symbols on the shield, but the text around the outside also reminds us that his beer beat Bass and other English brewers in competition in 1885. Molson Archive.

The Dominion Brewery’s India pale ale was renamed White Label Ale at some point after its triumph in the North Central and South American Exposition in New Orleans in 1885. Rather than simply mentioning the award, as in previous iterations of the label, Davies simply replaced the label with the award in what may be rightfully considered blatant showboating. Molson Archive.

The neck label from the Dominion Brewery’s White Label Ale clearly displays that the public would have had enough knowledge of the processes and ingredients in beer to understand that Kent hops were a significant selling point. Molson Archive.

Under Davies’s energetic management, production at the brewery grew annually. When he had started the brewery in 1878, he was not yet thirty, and he had the ambition of a young man. The year-over-year figures ought to be astonishing to a modern audience. He was adding the equivalent of a small modern craft brewery every year.

TABLE III. DOMINION BREWERY PRODUCTION 1886–1890

| Year | Imperial Gallons | Barrels |

| 1886 | 686,039 | 26,155 |

| 1887 | 837,674 | 31,936 |

| 1888 | 1,001,424 | 38,179 |

| 1889 | 1,078,239 | 41,108 |

| 1890 | 1,150,162 | 43,850 |

The spike in 1888 was the result of a plant expansion that was necessitated by his inability to keep up with demand for the product. The brewery’s frontage on Queen Street was expanded by two hundred feet. The activity prompted rumours that the Dominion Brewery was about to be sold. With typical humility, Davies announced that he was “putting in large new cellars and making other improvements which will make this by far the largest brewery in Canada, and which will enable me to supply all customers with Ales unequalled in fine quality in this and other markets.” It was to be the largest brewery with the best beer in the world.

Whether or not that was strictly truthful was immaterial, as people certainly believed the reputation. The following year, the brewery was purchased by a British consortium led by Sir Thomas Boord of Boord Distillers in London. English investors were looking for safe bets in Canada, having run out of profitable ventures to invest in at home. They ended up capitalizing the business for $1.2 million (nearly $45 million in today’s money) and retained Robert Davies as the managing director. A contemporary account from 1893 explains:

According to the Dominion Brewery’s letterhead, barrels were expected to be returned within six months. The scale of the operation is evident here: How many more barrels did Dominion have floating around the city? Sean Duranovich.

No higher praise could be accorded to Mr. Davies business skill and energy than the flattering encomiums pronounced at the company’s meeting in London by the English experts who were sent out to Canada to thoroughly inspect the establishment. Hard-headed men of established business reputations, they pronounced their opinions only after the most rigid personal inspection of every detail, and the result of their exhaustive examination was a plain admission that they had been greatly surprised at finding in Canada such a perfect establishment; in fact their whole report frankly admits that the inspection revealed to them a model brewery that would stand comparison with the best in any land.

The Dominion Brewery represented Canada in 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair. Its display was a twenty-five-foot-tall pyramid that was twenty feet wide at its base. It was constructed in the main of casks and barrels held in place by brass rails and adorned on every surface with pint bottles of different varieties of beer. Awards, certificates and gold medals served as eye-catching highlights. The larger trophies that the brewery had won were showcased in a specially constructed glass case at the rear of the exhibit. Robert Davies had little use for subtlety.

By this time, lager had been phased out of production at the brewery. According to Davies, “It was more troublesome, and I found that we had quite enough business without that.” The brands that were still in production were Export Ale, White Label India Pale Ale, Special Pale Ale, Jubilee Pale Ale and XXX Porter.

It was the fashion for breweries to have drawings of their facility on their stationery, but in the case of the Dominion Brewery, the size and scale is somewhat exaggerated. While there certainly were stables, they did not stretch all the way to Sumach Street on the right. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

In 1894, Davies found himself giving testimony in front of a commission on liquor traffic in Ontario. His answers reveal that even for a supremely confident manager, the concerns that brewers have from day to day have not changed in the last 120 years. The supply chain was a major concern. In a decade, the brewery went through 700,000 bushels of malt. Since the tax in those days was not on beer being sold, they paid approximately $550,000 in malt duty between 1882 and 1892. Another serious concern was making sure that there were enough kegs to ship product. Dominion employed its own cooperage on a back lot that was purchased when the English investors took over in 1890. The total value of the barrels the beer was shipped in came to somewhere between $100,000 and $125,000, or about one-tenth of the capitalization of the brewery. Sales were dependent on external factors. In 1885, sales were noticeably lower because people were drinking whiskey due to a particularly nasty epidemic of grippe.

It has been reported by a number of sources that Robert Davies owned 144 pubs within the city of Toronto. This is apocryphal. For one thing, he only became wealthy enough to do that in 1889, after the English investors capitalized the firm. This was at a time when the number of licenses in the city was quickly dwindling due to new regulations. Additionally, that number constitutes just over half of the licenses in the city. The figure is likely a conflation of the total number of taverns owned over a period of about two decades by Robert T. Davies and his son, Robert W. Davies, who worked for the Davies Brewery and the Copland Brewery. It would not have been a sound investment strategy at any rate.

This is the stable yard of the Dominion Brewery, a large courtyard at the northern end of the property. Note the several kinds of wagons employed by the brewery for the purposes of delivery. The brewer’s drays seem to have specialized in transporting barrels, with special closed vehicles for bottle delivery. Sean Duranovich.

Davies had been independently wealthy since 1890 and found himself retiring from the brewing industry in 1900 at the age of fifty-one. He had married Margaret Anne Taylor in 1871, daughter of John Taylor, whose family had owned 144 acres in the Don Valley. Three important landmarks resulted from the marriage. For one, Davies’s home, Chestnut Park, was located just off Broadview Avenue and had a commanding view of the Don Valley. Just across the valley was Davies’s stable, which composed the entirety of the Thorncliffe neighbourhood, a fiefdom large enough to earn him the nickname “King Bob” in the racing world. Finally, there was the Don Valley Brick Works, which Davies acquired in 1901 and subsequently built into the largest enterprise of its kind in the world.

The southern courtyard of the Dominion Brewery was used for returns rather than outgoing product. In the background of the shot, the returned barrels wait to be cleaned for reuse, while the bottling section is in the foreground on the right. Sean Duranovich.

The Dominion Hotel, which was attached to the Dominion Brewery, stands to this day and is one of the city’s few remaining Victorian hotels. What Robert Davies would think of the weekly Ukulele Jam, we can only speculate. Toronto Beer Week.

Robert Davies passed away in 1916 and left a legacy as a world beater. In all things, he strove to be the best. He was the only man in history to have jockeyed, trained, owned and raced horses in the Queen’s Plate. All of the businesses in which he was involved found themselves the largest in the country, at least for a time. His White Label Ale was entered in more international competitions and won more medals than any other beer in Ontario. However, his drive to succeed left a state of affairs at the end of his life where he was being sued by his extended family for having taken advantage of them in business related to the brickworks. He owned the deeds to nearly $1 million in real estate but provided for less than $4,000 in philanthropic donation. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Robert Davies was not especially interested in the betterment of society. Robert Davies was only interested in winning.

The Dominion Brewery was less successful without Davies’s monomaniacal drive. In 1926, it was purchased by the Hamilton Brewing Association. In 1930, the properties of the Hamilton Brewing Association were purchased by E.P. Taylor and formed part of the original basis of his empire. By 1936, the Dominion Brewery was considered redundant, and production was shifted to the Cosgrave Brewery. The Dominion Hotel, which was located adjacent to the brewery, has been rebranded the Dominion on Queen and continues to serve beer produced locally.