CHAPTER 14

THE PYGMY WARS: ESTONIA

The most northerly parts of the tsar’s empire that faced the Baltic Sea, Finland and Estonia, had longstanding ethnic, linguistic and cultural links. Like Latvia to the south, Estonia was home to Estonians, Russians who had settled in the area, and ethnic Germans – in the main, wealthy landowners, some of whom were descendants of settlers who had moved into the region during the time of the Teutonic and Livonian Knights. These German families had historically been staunch supporters of the tsars, in return for which they were granted considerable privileges, but during the 19th century there was a steady increase in Estonian nationalist feeling. Tsar Nicholas’ deliberate policy of Russification caused great resentment, leading to uprisings during the 1905 Revolution, followed by repression when Russian authority was restored.

Following the February Revolution and the fall of the tsar, Estonian leaders demanded greater independence. After some hesitation – due as much to the chaos in Petrograd as to any unwillingness to reduce the degree of control over Estonia – the Russian authorities gave permission in April 1917 for the creation of the Autonomous Governate of Estonia, followed three months later by an elected National Council, or Maapäev, led by Konstantin Päts. The degree of independence that would be granted to this new body remained the subject of disagreement, but just a few days before the October Revolution, the Estonian Bolsheviks under Jaan Anvelt seized power in Tallinn. The Bolshevik movement was not strong in Estonia and Anvelt struggled to establish any authority; in any case, his time in office proved to be short-lived, as German troops advanced almost unopposed into Estonia on the northern flank of Hoffmann’s offensive following the collapse of the Brest-Litovsk talks, and together with other Bolsheviks he fled to Russia. On 24 February, the Maapäev issued a declaration of Estonian independence, assuring full rights to all minorities and ending with a national rallying cry:

ESTONIA!

You stand on the threshold of a future full of hope in which you shall be free and independent in determining and directing your destiny! Begin building a home of your own, ruled by law and order, in order to be a worthy member of the family of civilised nations! Sons and daughters of our homeland, unite as one in the sacred task of building our homeland! The sweat and blood shed by our ancestors for this country demand this from us; our forthcoming generations oblige us to do this.429

For Estonia, it was a unique moment: the nation had never known independence before. On this occasion, it proved to be very short-lived. German troops arrived in Tallinn two days later and refused to recognise the declaration. The Maapäev was forced to go into hiding.

The Estonians had started to organise a national army, but the Germans rapidly declared this illegal and arrested several leading Estonian figures, including Päts, who was imprisoned first in Estonia, and ultimately in Grodno in Poland. Despite this, Estonian independence was recognised by the Entente Powers, and, with the tide turning against Germany on the Western Front, many in Estonia looked forward to the future with real hope. The Germans had their own plans for Estonia and tried to create a new political entity combining Estonia with much of Latvia under the control of the Baltic Germans, who were encouraged to declare the creation of the Baltischer Staat or Baltic State, with its capital in Riga. The first head of this new state was to be Adolf Friedrich, Duke of Mecklenburg, but the Baltic State would be an autonomous part of the German Empire. Until Adolf Friedrich could take up office, a regency council of ten – four Baltic Germans, three Latvians, and three Estonians – ran the government in Riga under the close watch of Ober Ost.

Only Germany recognised the status of the new Baltic administration, and as it became increasingly clear in Berlin that the war would end unfavourably, attempts were made to try to create a government that would be acceptable both to the Estonians and the rest of the world. In October, Prince Max von Bayern sent a telegram to Ober Ost with instructions to set up a civilian administration; the intention was to create a series of such governments in the territories overseen by Ober Ost, starting in the Baltic region, but time ran out before the policy could even begin.430 After the end of hostilities in the west, Konstantin Päts was released from captivity and recognised by the new German government as the head of the Estonian government.

As German authority collapsed, Päts struggled to create the institutions that would be vital for the survival of an independent Estonia. In particular, he needed to create an army that could protect the nation from a variety of forces. Ever since the establishment of the Maapäev, a paramilitary Omakaitse (‘Citizen’s Defence Organisation’) had existed, with Ernst Põdder, a former officer in the Russian Army, as its commander. During the German occupation, the Omakaitse was forced to operate clandestinely, but with political control back in the hands of the Estonians, the force was now organised to deal with the multitude of threats that the fledgling nation faced.

There were several military powers operating within Estonia. By far the largest was the German Army, which was in the process of withdrawing and returning home in keeping with the terms of the Armistice. As morale in the army collapsed, many soldiers didn’t wait for orders and simply drifted away from their formations, attempting to make their way home, but most continued to obey orders. Päts tried in vain to persuade the Germans to hand over weaponry to the Omakaitse, but in the main, the Germans either took their weapons home with them or destroyed them.431 Fortunately for the Estonians, help was at hand. The newly independent Finland to the north, whose people had a long history of links with the Estonians, provided both weapons and ammunition, though in limited amounts.

In addition to the Germans, there were large numbers of anti-Bolshevik Russian troops in Estonia. These formations had largely been raised from released Russian prisoners of war and anti-Bolshevik Russians who first gathered in Pskov where their officers squabbled ineffectively amongst themselves over questions of precedence. From there, they were forced to flee to Estonia, where General Alexander Pavlovich Rodzianko – the nephew of the former chair of the Duma – managed to organise them into something resembling a military formation that now became known as the White Russian Northern Corps. Whilst Rodzianko remained its commander, the corps was subordinated to General Nikolai Nikolaevich Yudenich, who had commanded the Russian Caucasus Army during the First World War. In some respects, his appearance was deceptive; contemporaries described him ‘physically slack and entirely lacking in those inspiring qualities which a political and military leader of his standing should possess’.432 Despite this, he achieved considerable successes against the Turks during the war, but after the fall of the tsar he was dismissed from his post for insubordination and returned to Petrograd. He was involved in the attempt by Kornilov to oust the Kerensky government in August 1918 and fled to Finland when Kornilov and his associates were arrested. In Finland, Yudenich joined the ‘Russian Committee’, an organisation set up to oppose the Bolsheviks, and was appointed commander of all White Russian forces in the northwest. Like many Russian generals of the tsarist era, he was bound by the prejudices with which he had grown up, and he refused to accept the reality of independent Finland. Rather than try to build an alliance with the strongly anti-Bolshevik Finns, he preferred to relocate to Estonia, where he created the Northern Corps. Whilst this force would be prepared to fight against any Bolshevik intervention, the presence of so many foreign soldiers was nonetheless not entirely welcome to the Estonians.

As the fighting on the Western Front drew to a close, a Bolshevik intervention in the Baltic region grew ever more likely. Lenin had never intended to be bound by the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and the collapse of Germany effectively made the treaty meaningless. The Red Army, successor to the Russian Army of the tsars, was now a far more powerful force than it had been when Hoffmann brushed it aside in early 1918, though it remained very limited in terms of logistic and other support. The disorganised, untrained Red Guards had undergone at least a degree of formal training, and the incorporation of large numbers of soldiers from the Imperial Russian Army further improved the overall level of practical knowledge and ability in the front line. Nevertheless, whilst it could probably fight and win short campaigns, sustained operations still posed huge challenges for the Red Army.

With the dissolution of Ober Ost and the departure of German troops, there was an opportunity for Russia to regain some of its lost territories. From the point of view of the Russians, this was essential. Prior to the First World War, the Russian capital had been safe from foreign invasion, but the loss of Finland and the Baltic States suddenly created a substantial threat. From Narva in northeast Estonia to Petrograd was a mere 81 miles (130km), and the presence of Yudenich’s troops was therefore a significant threat to the Bolsheviks, particularly as the White forces in the Caucasus, Siberia and Ukraine had already drawn the attention of much of the Red Army. Even though the capital was now Moscow, the loss of such a major city would be a huge – possibly irrecoverable – blow to the prestige of any Russian government.

Lenin, Trotsky and other leading Bolsheviks had every reason to feel beleaguered. White Russian forces were threatening from the east and south, while the western fringe of the Russian Empire had been torn away by the Germans. Throughout 1917, British, French and American ships had brought a steady stream of war materiel to Archangelsk in the north, but the growing disruption of the Russian railways after the February Revolution resulted in large stockpiles building up around the port. When Goltz and the Baltic Division were landed in Finland, there were concerns that the Germans might be able to capture the stockpiles in northern Russia; rather more realistically, the Western Powers had no intention of allowing the stockpiles of modern armaments to fall into the hands of the Bolsheviks, who had made no secret of their intention to export their revolution to the rest of the world. There had been widespread agreement that the troops of the Czechoslovak Legion should be enabled to reach Western Europe, but now that they were embroiled in the Russian Civil War, the presence of western troops in Archangelsk might provide an opportunity for concerted action to overthrow the Bolsheviks. To that end, a mixed force of British, Australian, French, American, and even Serbian and Polish troops was dispatched to Archangelsk. Many of the British contingent were marines who had little experience of war; some were very young, and others were former prisoners of war who had recently been released by the Germans. In some cases, they were denied home leave and were dispatched to northern Russia at short notice, resulting in widespread morale problems. Once there, they found themselves slowly drawn into combat against the Bolsheviks. They succeeded in advancing about 100 miles (160km) south along the railway line leading to the Russian interior before a decision was made to pull back to a tighter perimeter and ultimately to evacuate the expedition entirely; after suffering losses in an attack on a Russian village, one British company of marines mutinied and refused to attack again. Several men were court-martialled and condemned to death, but after intervention by British politicians the sentences were not carried out.433

The opportunity to strike a potentially decisive blow against one of these hostile powers encircling Russia was therefore most attractive to the Bolsheviks. Although this has been described as the Soviet Westward Offensive, and according to one source was given the codename ‘Target Vistula’, it seems that there was no central planned offensive.434 Rather, a series of uncoordinated movements occurred in the same region, with little if any overall coordination. However, the animosity of the Soviet leadership towards the Baltic States certainly played a part in the development of events. Lenin told his staff:

Cross the frontier somewhere, even if only to the depth of a kilometre, and hang 100-1000 of their civil servants and rich people.435

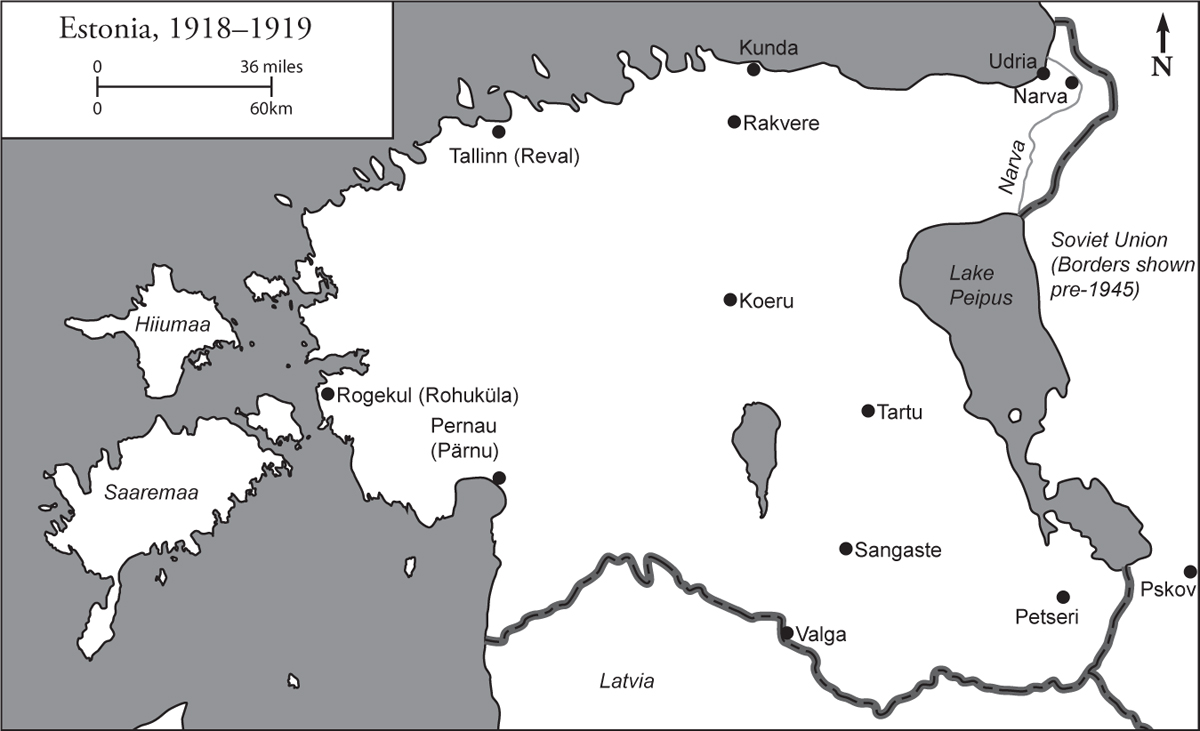

As with so many wars, the geography of the region dictated the course of the campaigns. The border between Estonia and Russia is dominated by Lake Peipus, with the result that land routes for combat operations are either north or south of the lake. To the north, the confrontation would be across the River Narva, with the city of Narva itself forming part of the battlefield. This area offered the most direct route for a Russian advance towards the Estonian capital, Tallinn (previously known to both the Russians and Germans as Reval), but the northern flank of any such operation would be exposed unless the sea was controlled by the Russian Navy. Consequently, naval operations would play a major role in the fighting. To the south of Lake Peipus, any Russian advance to the Baltic coast, roughly along the border between Latvia and Estonia, could conceivably come under pressure from either flank. As a result of these geographic constraints the conflict in the northern part of the Baltic region, which became known as the Estonian War of Independence, saw repeated thrusts by either side north of Lake Peipus, and although the same territory changed hands on several occasions to the south of the lake, the fighting tended to follow the same pattern: a Bolshevik advance, and an Estonian counterattack against its flanks.

The most northerly Soviet formation involved in the offensive was the Seventh Red Army under the command of the Latvian Jukums Vācietis, who attacked towards Narva with 6th Red Rifle Division. The experienced core of the old Russian Army was gone; many of its troops, sick of the war, had returned to their homes and had no desire to take part in further fighting, and few officers of the old army were regarded as acceptable by the Bolsheviks. The division was made up of volunteers, many of them from the Narva region, with just a sprinkling of veterans. Opposing them were elements of the Estonian Defence League and the German Infantry Regiment 405, originally part of 203rd Infantry Division and the only organised German formation left in northeast Estonia. After a brief battle on 28 November 1918, in which the Soviet armoured cruiser Oleg and two destroyers supported the main attack, the Germans and Estonians retreated from Narva, leaving the city in Russian hands. A few days later, the 6th Red Rifle Division pushed on towards Tallinn, and though the newly created units of the Estonian Army, ill-equipped and poorly trained, were dispatched to the front as they became available, the Russians seized Rakvere on 15 December and Koeru ten days later, finally reaching a point only 21 miles (34km) from the Estonian capital by the end of the year.

At the same time, a second Soviet advance developed from south of Lake Peipus. The Soviet 2nd Novgorod Division began to attack westward on 25 November, and made good progress in the face of weak resistance by the White Russian Northern Corps. The 49th Red Latvian Rifle Regiment, part of the 2nd Novgorod Division, took Tartu on 24 December, leaving more than half of Estonia in Russian hands by 1919, but this success was to mark the high-water mark of the Russian advance. Heavy snow, poor roads, and a chaotic supply situation made the prospect of further gains very unlikely without major reinforcements.

In the areas occupied by the Bolsheviks, there was widespread repression of anyone suspected as being a nationalist. In addition, the Bolshevik policy of targeting the ‘bourgeois classes’ resulted in a variety of individuals, from clergy to teachers, being arrested and shot. It has been estimated that over 500 people lost their lives as a result; not a huge number in the context of the deaths in the First World War, but sufficient to encourage a growth in partisan activity, which further disrupted Russian supply lines.436

The reduction of territory controlled by the Estonian nationalists worked in favour of the defenders, who now contended with much shorter supply lines. Colonel Johan Laidoner, who like most Baltic officers of his generation had served in the tsar’s armies, had commanded the Estonian Army’s first formations, hastily grouped together into an infantry division, and on 23 December was appointed commander of the entire army. He used the lull in fighting to good effect, creating a second infantry division and the staff of a third. In addition, the country’s German community raised a Baltic Battalion of volunteers, a welcome boost both in military and symbolic terms: Estonia’s Baltic Germans were explicitly supporting the Estonian government, rather than seeking to secure control themselves, as the Germans had originally intended. Almost immediately, the Baltic Battalion was deployed in the front facing towards Narva. The dockyards and railway works of Tallinn improvised a variety of armoured cars for the Estonian Army, which despite their limited mobility – they were badly underpowered and became bogged down in even slightly soft ground – proved to be effective weapons, not least because of the fear with which they were regarded by many in the Red Army.437 Whilst the old Russian Army had possessed large numbers of armoured cars – mainly supplied by Britain and France – and Bolshevik units elsewhere, even in Latvia, still operated many of these vehicles, they were conspicuously absent from Red Army units in the far north.

Help for Estonia also arrived from the west. Even as the war in the west came to an end, British officials were discussing how to further the cause of anti-Bolshevik forces. Lord Balfour, the British foreign secretary, wrote a memorandum in November, concluding:

For us no alternative is open at present than to use such troops as we possess to the best advantage; where we have no troops, to supply arms and money; and in the case of the Baltic provinces, to protect, as far as we can, the nascent nationalities with our fleet.438

As the Red Army pressed into Estonia, a delegation arrived in London to seek support. British diplomats responded that it would not be possible to send troops, but warships and armaments might be available, leading immediately to objections from the navy; the Baltic area was heavily mined and it was unwise to dispatch warships before the mines had been cleared. Nevertheless, the political necessity to intervene in the Baltic overruled purely naval concerns and on 22 November, after escorting the German High Seas Fleet into British waters where it was to be interned, the light cruiser HMS Cardiff and four other cruisers of the 6th Light Cruiser Squadron set off for the Baltic, accompanied by nine destroyers and seven minesweepers, under the collective command of Rear-Admiral Edwyn Alexander-Sinclair. The orders issued to him were a masterpiece of vagueness: he was to proceed to Libau (now Liepāja) and thence to Tallinn, ‘to show the British flag and support British policy as circumstances dictate’. He took with him a substantial store of weapons and ammunition and was to advise the governments of both Estonia and Latvia that they had to be responsible for their own defence. In the event of interference by Bolshevik warships, he would be able to call on the support of British battleships, which would soon deploy to Copenhagen.439

Problems in obtaining sufficient fuel supplies – the minesweepers of Alexander-Sinclair’s force were coal-fired – led to the warships proceeding beyond Denmark without the minesweeper force. Late at night on 5 December, as they sailed past the Estonian island archipelago that had been the scene of fighting in 1917, the warships found themselves in a previously unsuspected German minefield. HMS Cassandra struck a mine and rapidly sank; all but 11 of her crew were rescued. Two accompanying sloops were also lost to mines. A second cruiser, HMS Calypso, had been damaged after striking a submerged wreck, and two destroyers sustained light damage when they collided with each other; the rescued crew of Cassandra was placed aboard these three ships, which returned to Britain.

The somewhat diminished British force arrived in Tallinn on 7 December, where it received an enthusiastic welcome. With Russian forces close to his capital, the increasingly desperate Päts suggested that Estonia should become a British protectorate and that Britain should immediately deploy troops in the Baltic region. This was clearly contrary to the intentions of the British, who nevertheless reassured Päts that guns and ammunition were en route (they were being carried by the minesweepers, which were still awaiting coal in Copenhagen). Unwilling to allow the Bolsheviks a free hand, Alexander-Sinclair decided to interpret his instructions as loosely as possible and on 13 December dispatched two cruisers and five destroyers east along the coastline to a point near Narva, where they brought the coastal road under shellfire and destroyed a vital bridge, further disrupting the supply lines of the Seventh Red Army. A few days later, the British ships helped land a force of Estonians on the coast to operate in the rear of the Bolshevik troops. At about the same time, as if to confirm the upswing in the fortunes of Estonia, the first of 2,000 Finnish volunteers began to disembark from ships in Tallinn.440

The Russian naval authorities suspected the presence of British warships from interception of wireless traffic but were uncertain of their strength. The fleet in Kronstadt was in poor shape following the October Revolution, and attempts to carry out a reconnaissance of Tallinn by submarine were unsuccessful, with repeated mechanical problems; as will be seen, this was a recurrent issue. Many ships had been poorly maintained during the First World War, and spare parts for the vessels – most of which had been built outside Russia – were hard to obtain. Even when they were available, the Bolsheviks often lacked skilled engineers to carry out repairs.

After the British bombardment that disrupted supply lines between Narva and the front line, Vācietis asked for naval support for his Seventh Army. On 24 December, a task force consisting of the battleship Andrei Pervozvanni, the cruiser Oleg and three destroyers was assembled under the command of Fyodor Fyodorovich Raskolnikov, the commissar of the Baltic Fleet, with orders to carry out an armed reconnaissance and to destroy the British warships – but only if the balance of power was strongly in favour of the Russian force. It is likely that this group of vessels represented a very large proportion of all the warships in Kronstadt that were seaworthy. A plan was drawn up for the destroyers Spartak and Avtroil to penetrate into Tallinn harbour, where, in addition to looking for British warships, they would shell two small islands to determine whether any defensive batteries had been positioned there. Should they encounter British forces, they were to withdraw towards the island of Gogland, where Oleg would be waiting; if a further withdrawal were required, the three ships would pull back towards Kronstadt, in order to bring the pursuing British ships within range of Andrei Pervozvanni and her 12-inch guns.

Raskolnikov had played an important part in the Kronstadt Mutiny of 1917, and had held a variety of posts since the October Revolution. He arrived in Kronstadt on 25 December to discover that the destroyer Avtroil had developed mechanical problems. Rather than delay the operation, he decided to proceed with only Spartak. As Spartak set off, Raskolnikov received a signal that the destroyer Azard, which had been patrolling the area and therefore might have been available to him as a replacement for the Avtroil, was unable to accompany the mission due to a shortage of coal. Towards dusk, Spartak encountered the Russian submarine Pantera, which was returning from a reconnaissance of Tallinn. The submarine reported no sign of any smoke rising from ships in the Estonian port, but a later account suggested that, like other Soviet submarines, the Pantera probably didn’t enter the port at all due to major mechanical problems and was forced to make its observations from some distance. Spartak and Oleg dropped anchor and spent the night near Gogland. The following morning, they waited in vain for Avtroil to join them, and when they received a signal informing Raskolnikov that the destroyer’s mechanical problems showed no sign of resolution, the commissar decided to press on with just Spartak; Oleg would wait near Gogland to provide support should the destroyer make a hasty withdrawal.

Alexander-Sinclair’s force had undergone further changes. As will be described later, the situation in Latvia required urgent intervention and he dispatched two of his cruisers and half his destroyers to Liepāja; the return of Calypso and the much-delayed arrival of the minesweepers was therefore greatly welcomed, not least by the Estonians who took possession of the 5,000 rifles and other weapons that had been brought to equip their army. The crews of the British warships had been invited to a civic reception on 26 December and the enthusiasm of the sailors was probably considerably enhanced by the promise of a dance after the dinner, for which women would be ‘hired’. While preparations for the event were under way, there was the sound of distant naval gunfire. Reports arrived swiftly that a Russian vessel had been spotted in Tallinn Bay, attempting to bombard coastal positions. The British personnel hastily returned to their ships and began to prepare for action. As smoke began to rise from the funnels of the two British cruisers and four destroyers, Raskolnikov ordered Spartak to reverse its course in order to draw the British onto the guns of Oleg.

Raskolnikov’s plan had always been ambitious: his destroyer was nearly 90 miles (145km) from Gogland, and even at maximum speed it would take nearly three hours to reach the Oleg. Although the British cruisers had a similar maximum speed to the Spartak, the accompanying destroyers were faster, and any mishap aboard the Soviet destroyer – mechanical problems, or damage from British shellfire – might prove fatal. Like Avtroil, Spartak was not in perfect condition and almost inevitably developed engine problems as she attempted a sustained period of maximum speed. As the British destroyers closed in, Spartak’s bow gun tried to fire on the pursuing vessels. To do this, the turret had to be traversed until it was pointing back past the bridge, and when the gun was fired, its blast demolished Spartak’s charthouse and damaged both her bridge and helm.441 Shortly after, the destroyer ran aground on the Kuradimuna sandbank. Attempts to scuttle the destroyer failed when the seacocks jammed, and British sailors from the destroyer HMS Wakeful came aboard to seize the ship. Raskolnikov attempted to hide in the hold under several sacks of potatoes, but was taken prisoner together with the rest of the crew.

One of the officers aboard HMS Caradoc later wrote an account describing the state of Spartak and her crew:

The crew themselves, very dirty and in a dreadfully dirty ship, appeared pleased at being captured. Many of them had articles of various sorts, such as cameras and furs, obviously looted from shops and houses, which they sold to our crew at ridiculous prices, some even offering the things gratis, possibly fearing to be caught by Russians with them in their possession. Much valuable information was found in the ship; also an amusing signal which had been dispatched: ‘All is lost. I am chased by English’.442

Raskolnikov’s despairing signal was not the only piece of intelligence gained with the capture of Spartak. There was also a message from Trotsky instructing Raskolnikov that the British warships must be destroyed and confirming the plan to lure them onto the guns of Oleg. The two British cruisers promptly set sail in order to locate and destroy the Russian cruiser. To their disappointment, they found the coast of Gogland deserted and returned to Tallinn. On their outward voyage, they had spotted a ship, presumed to be another Russian destroyer, cautiously sailing west, and had decided not to engage it, but now they signalled the British destroyers in Tallinn to put to sea with the intention of trying to capture the Russian ship. Raskolnikov, who was still being held aboard Wakeful, described what transpired:

Then, from above our heads, there was a sudden, deafening sound of gunfire, and after it that soft noise made by the compression of the recoil-absorber which always follows the firing of a gun. There could be no doubt about it: the shot had been fired from the destroyer in which we were held captive. We eagerly rushed to the portholes, but we were so far down in the hold that the field of vision from any of these portholes was small. We could not see anything except the other British destroyers which were sailing near us. The firing ceased as suddenly as it had started. The engine also suddenly stopped. There was a strange silence. The destroyer Wakeful had come to a halt. We were taken up to the top deck for exercise. A sad spectacle met our eyes. Right next to us lay the destroyer Avtroil, with her topmast awry. She had just been taken by the British, but the red flag still flew over her. The British squadron had come round her from behind and, cutting her off from Kronstadt, had driven her westward, into the open sea. The British commander had ordered us to be let out for exercise at the very moment when Avtroil surrendered, so as to wound our revolutionary self-esteem and mock this defeat suffered by the Red Navy.443

The two captured destroyers were handed over to the Estonians, who renamed them and put them to use in their new navy. With the exception of Raskolnikov and Avtroil’s commissar, the crews were also handed over; despite British protests, about 40 were later executed.

Raskolnikov and his fellow commissar were eventually exchanged for 18 British personnel being held prisoner by the Bolsheviks. Unfortunately for Raskolnikov, a grim fate awaited him. He served as Soviet ambassador to Estonia, Denmark and Bulgaria, but in 1937 was recalled to Moscow. He delayed his return until the following year, but then learned that he had been dismissed. Fearing that he would be a victim of Stalin’s purges, he published an open letter to Stalin in which he acknowledged that he had been a friend of Trotsky, and went on to denounce the purges. Shortly after, he died in Nice, either as the result of an unexplained fall from a window, or possibly from poisoning.

With some 13,000 men ready for action, the Estonian Army began a counteroffensive in January 1919. British ships were now in firm control of the sea, and on 4 January the two light cruisers, accompanied by the destroyer Wakeful, subjected several Russian positions near Narva to a heavy bombardment. A detachment of Finnish and Estonian troops was landed in the rear of the 6th Red Rifle Division at Kunda late on 10 January; the following day, Rakvere was retaken, and the Estonians advanced steadily towards Narva. A further seaborne operation was carried out on 18 January at Udria, and this contingent moved swiftly into the northern part of Narva. The rest of the city was liberated the following day.444 Leon Trotsky, who was personally directing the defence of the city, narrowly escaped being captured.445

With the northern part of the country free of Soviet forces, attention turned south. Several armoured trains had been created to provide the Estonian Army with much-needed fire support. Mounting a variety of weapons, ranging from machine-guns to 6-inch artillery, the trains were a potent asset, though of course their deployment was dictated by the rail network. Another of the new formations raised during the winter was the Tartumaa Partisan Battalion, created by Lieutenant Julius Kuperjanov; the battalion’s young, energetic personnel rapidly gained a reputation for aggression and daring, and the unit liberated the town of Tartu on 14 January, attacking from aboard armoured trains that broke through the Bolshevik lines and entered the town before Estonian infantry disembarked. From here, it was possible to plan an attack to retake Valga, which was astride the only rail link to Riga and the south. The main approach to Valga from the north ran past Paju Manor, and this now became the focus of fierce fighting. Estonian partisans seized the manor on 30 January, but were swiftly driven back by a battalion of Red Latvian Rifles.

The Estonians found themselves at a disadvantage. Retreating Russian units had destroyed the railway bridge at Sangaste, a little to the north, preventing the Estonians from deploying their armoured train. By contrast, the Latvian Rifles had fire support from their own armoured train, in addition to several armoured cars. Undaunted, Kuperjanov led his battalion in an attack on the manor on 31 January across open ground. Along with many of his men, he was cut down by the withering fire of the defenders, but towards the end of the day a body of Finnish volunteers, in a battalion named the ‘Sons of the North’, arrived as reinforcements. The combined body of Finns and Estonians penetrated into the grounds of the manor, clearing it of Bolshevik defenders in bitter fighting. The following day, the Latvian Rifles withdrew from the area, allowing the Estonians to take Valga without further fighting.446

With the railway line from Latvia now in Estonian hands, it became increasingly difficult for the Soviet forces in central Estonia to coordinate their movements, and they were forced to withdraw east. By the end of February 1919, all Estonian territory had been liberated by the nationalist forces. In addition, the Estonians captured 35 field guns, several dismounted naval guns, and thousands of small arms, together with copious stocks of ammunition. The need to rebuild Bolshevik positions in the north forced the Russians to divert troops from Latvia, where they had been enjoying considerable success. The Estonians now drew up a mutual defence agreement with the Latvian government, and began to prepare for an attack against Bolshevik forces in northeast Latvia.

Meanwhile, in the north the battered Seventh Red Army had received substantial reinforcements, and launched a major assault on Narva on 18 February. The Estonian 1st Division, reinforced by the White Russian Northern Corps, successfully beat off the attacks that continued until late April, though the city suffered considerable damage from artillery fire. To the south, a renewed Soviet attack overran southeast Estonia in the first half of March and a gap began to open between the Estonian 1st and 2nd Divisions. To counter this, the Estonian Army deployed its new 3rd Division in the gap and launched a counterattack, recapturing Petseri at the end of the month. Confused fighting in the marshy area continued for several weeks before the Estonians were able to secure their positions, with support from more new military formations: Latvians who had fled to Estonia were formed into a new brigade, and a further 7,000 anti-Bolshevik Russians and Ingrians (from Ingermanland, the region of Russia immediately to the east of Estonia) served alongside the existing Estonian and Finnish units.447 Throughout this phase of the fighting, the Estonians were able to make efficient use of their limited forces as a consequence of well-organised logistical support. By contrast, the Red Army’s supply system was chaotic, and its medical services almost non-existent.448

The Estonians had fought off two invasions, and it appeared that the Bolsheviks were interested in peace negotiations. The Hungarian Communists offered themselves as mediators, but Estonia came under pressure from its western supporters, particularly the British, who threatened to withdraw their support; there was still hope that Estonia might be used as a base for an attempt to overthrow the Bolsheviks, and this would clearly be impossible if Estonia and Russia were to agree terms for peace. After a period of preparation, the Estonians and their allies decided to launch an attack of their own. Estonian accounts describe the operation that followed as an attempt to push the Bolsheviks as far as possible from Estonian territory, but the major role played by White Russian forces suggests that there was at least a hope that such an attack towards Petrograd might destabilise the Soviet regime and perhaps give a non-Bolshevik party a chance of seizing power.449

On 13 May, Yudenich ordered Rodzianko to commence an operation named ‘White Sword’. His 3,000-strong corps attacked at Narva, surprising and overwhelming the 6th Red Rifle Division. Supported by naval units off the coast, the White Russians advanced swiftly and, in anticipation of their arrival, the garrison of the Krasnaya Gorka fortress mutinied. This was a devastating development for the Bolsheviks, as the presence of White Russian forces in this fortress – on the Baltic coast, perhaps two thirds of the way from the Estonian frontier to Petrograd – would effectively make it impossible to defend Petrograd. Despite being aware of the mutiny, the Estonian authorities took several days to pass the information to Rodzianko and Yudenich; instead, they encouraged the Ingrian detachment within their forces to try to reach the area, perhaps preferring that the lands to their east should come under the control of the friendly Ingrians rather than the White Russians. The Ingrian force proved too weak to reach the mutineers, and eventually the Estonians informed Rodzianko, nearly two days after the mutiny had commenced.

Before either the White Russians or the Royal Navy warships operating in the Gulf of Finland could come to the aid of the mutineers, Josef Stalin – who had been given the task of defending the Russian capital – intervened. Born Josef Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in his native Georgia, he was educated at first for the priesthood but became an atheist and was involved in revoutionary groups before he had finished his studies. He was an early adherent of Lenin and proved adept at organising Bolshevik groups in the early years of the 20th century, resorting to criminal means to secure funds and showing the first signs of the ruthlessness that was to become his hallmark. Like Trotsky, he was arrested and exiled to Siberia, but travelled to Petrograd after the February Revolution, supporting Kerensky at first but then playing a leading role in the work of the Bolshevik Central Committee during the October Revolution. He was appointed People’s Commissar for Nationalities’ Affairs but like many leading Bolsheviks was required to take command of the formations of the fledgling Red Army against White Russian forces; he soon became known for his uncompromising policies towards White Russian officers, ordering the execution of many, as well as taking draconian measures against Bolshevik deserters and peasants who showed any reluctance to support the Bolsheviks.

Outside Petrograd, Stalin acted with characteristic resolution and force. Two of the large warships in Kronstadt were ordered to commence a bombardment of the fortress, while a force of naval volunteers assembled as an infantry formation to storm the position. After two days of rebellion, even as Rodzianko, finally aware of developments, was ordering his troops to try to reach the mutineers, the ruins of Krasnaya Gorka were back in Bolshevik hands. In another characteristic act, Stalin ordered the execution of nearly 70 Russian naval officers from the Kronstadt base, on the basis that they had been planning a similar revolt. Although Stalin claimed to have documentary evidence of this, including proof that the British had financed the planned mutiny, no such document was ever produced.450

A second Estonian offensive took place south of Lake Peipus, and a combined Estonian and White Russian force known as the Petseri Battle Group crossed into Russia and seized Pskov on 25 May. Almost immediately, the White Russians appeared to lose interest in fighting against the Red Army, turning their attention against those that they regarded as Bolshevik sympathisers and supporters. Given the prejudices of the region at that time, it was almost inevitable that all Jews were automatically regarded as being in this group, and there was widespread looting, murder and imprisonment.451 From Pskov, the Estonians pushed on to the Velikaya River, but it became increasingly clear to the Estonians that their advance was unsustainable, not least due to the growing resentment of the local population towards the behaviour of Rodzianko’s troops. The Estonians removed the White Russians from their own line of command, and the Northern Corps reorganised itself into the Northwestern Army. The Bolsheviks counterattacked on 19 June with the reorganised 6th Division, reinforced by the 2nd Division, and rapidly eliminated most of the gains made by the Northern Corps.

Meanwhile, Alexander-Sinclair had been relieved by Admiral Sir Walter Cowan and the British 1st Light Cruiser Squadron. Whilst Cowan’s warships were able to control the Estonian coastline, the presence of Russian warships in Kronstadt continued to pose at least a theoretical threat. Fortunately for Cowan, he found himself working alongside a British naval officer, Augustus Agar, who was operating coastal motor boats on behalf of the British Foreign Office, attempting to maintain links with British spies inside Russia. One of them, codenamed ST-25, was the last important agent still on Bolshevik soil, but arranging a rendezvous to collect him seemed almost impossible. Frustrated in his attempts, Agar contacted Cowan and offered to use his motor boats to attack the Russian battleships that had been used to bombard Krasnaya Gorka. There was an exchange of signals with London, as a result of which Cowan was advised that the motor boats were to be used for intelligence purposes only, unless specially directed by an officer of flag rank. Cowan was determined to get his ships into action, and decided to stretch his orders to the limit; he advised Agar that he could not specifically order the motor boats to attack the Russian battleships, but if they did Agar could count on Cowan’s support.

On 17 June, Agar set off with two boats. One turned back after developing mechanical problems and news arrived that the Russian battleships had withdrawn and been replaced by the cruiser Oleg, which had been part of Raskolnikov’s disastrous foray against Tallinn, but Agar pressed on undaunted and made his approach to Kronstadt during the short hours of the summer night. After a fierce exchange of fire with Soviet destroyers, he approached the Tolbukin lighthouse where he was forced to run his boat aground on a breakwater to make repairs. Still under constant fire, he and his men patched up the boat, and then launched a torpedo at Oleg before turning and running for the Finnish coast. The 7,000-ton cruiser, which had fought in the Russian Navy’s battle with the Japanese fleet at Tsushima in 1905, was struck by the torpedo and sank. Agar and his crew made good their escape in the resultant confusion, still under fire. For this mission, he was awarded the Victoria Cross and promoted to lieutenant commander.452

Agar wasn’t finished. Cowan wished to eliminate any further threat from the battleships of the Russian Baltic Fleet and planned a new raid on Kronstadt. This operation was codenamed ‘RK’ in honour of Cowan’s friend Admiral Roger Keyes, who led the raid on Zeebrugge in April 1918. On 18 August, Agar led a group of seven small boats towards Kronstadt. On this occasion, he stayed outside the port while the other six boats, led by Commander Claude Dobson, made an attack at night, while British aircraft carried out an air raid to distract the defenders. Cowan’s destroyers and cruisers waited a short distance away, ready to intervene if the Russian warships attempted to pursue Agar’s force.

The attack achieved complete surprise; the small flotilla passed the silent Russian guardship at the entrance to the harbour and made their attack, and the first that the Russians knew of the presence of the British was an explosion as a torpedo struck the submarine depot ship Pamiat Azova, which swiftly sank. Lieutenant Gordon Steele was aboard a boat commanded by Lieutenant Archibald Dayrell-Reed, with orders to attack the battleship Andrei Pervozvanni:

As Dayrell-Reed’s boat entered the harbour, fire was opened on us, first from the direction of the dry dock and afterwards from both sides. We headed for the corner where our objectives, the battleships, were berthed. Almost simultaneously we received bursts of fire from the batteries and splashes appeared on both sides. Instinctively I ducked as the bullets whistled past. I turned round and was about to remark to Dayrell-Reed, ‘Where are you heading?’ as we were making straight for a hospital ship, when I noticed that his head was resting on the wooden conning tower top in front of him. He had been shot through the head. Despite his considerable weight, I was able to lower him into the cockpit. At the same time I put the wheel hard over and righted the boat on her proper course. We were now quite close to Andrei Pervozvanni. Throttling back as far as possible, I fired both torpedoes at her, after which I stopped one engine to help the boat turn quickly. As I did this we saw two columns of water rise up from the side of Petropavlovsk [the second Russian battleship] and heard two crashes. I knew they must be Dobson’s torpedoes which had found their target. Then there was another terrific explosion nearby. We received a great shock and a douche of water. I realised that the cause of it was one of our torpedoes exploding on the side of the battleship [Andrei Pervozvanni]. We were so close to her that a shower of picric acid from the warhead of our torpedo was thrown over the stern of the boat, staining us a yellow colour which we had some difficulty in removing afterwards. [Missing] a lighter by a few feet [we] followed Dobson out of the basin. I had just time to take another look back and see the result of our second torpedo. A high column of flame from the battleship lit up the whole basin. We passed the guardship at anchor again. Morley [the mechanic aboard the boat] gave her a burst of machine-gun fire as a parting present and afterwards went to see what he could do for Reed.453

Three of the British boats were sunk by Russian gunfire, with the loss of 15 crew killed, including Dayrell-Reed, and nine captured from the sinking boats; the Russian account states that the guardship actually spotted the boats as they penetrated the harbour, but chose not to fire for fear of hitting friendly vessels beyond the boats. This does not of course explain why the guardship failed to raise the alarm.454 For their part in this action, both Dobson and Steele were awarded the Victoria Cross.

Agar had intended to use the attack as cover for another attempt to reach agent ST-25, but was unable to do so. The agent’s real name was Paul Dukes, and he had worked for many years as a concert pianist in the Petrograd Conservatoire, gathering intelligence and helping White Russians to escape to Finland. It was a remarkable achievement for a man without any training before he was sent to Russia – he was merely told to establish contact with the agents of his predecessor, the naval officer Francis Crombie, who had been killed by the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. Without knowing even the names of these agents, he succeeded in re-establishing and even building on the network. He wore many disguises and adopted a variety of aliases, infiltrating the Russian communist party, the Comintern (the international organisation dedicated to worldwide revolution) and even the Cheka – he had a forged document that stated that he was a member of the Cheka, allowing him to pass most checkpoints without question. For a while, he adopted the role of a poor Russian, growing his beard and hair, but when he heard that the Cheka were seeking him he shaved and smartened his appearance, taking pride that many of his acquaintances no longer recognised him. Not long after, he was aboard a tram, disguised as a Russian soldier, when he saw a known Cheka and realised he had been spotted by a known informer:

I did not wait to make sure … Passing the Tsarskoselsky station I jumped off the car while it was still in motion, stooped beneath its side till it passed, and boarded another in the opposite direction. At the station I jumped off, entered the building and sat amongst the massed herds … till dusk.455

Under his guise as an ordinary Russian, he was conscripted into the Red Army. His observations of the causes of the failure of the various White forces are interesting:

The complete absence of an acceptable programme alternative to Bolshevism, the audibly whispered threats of landlords that in the event of a White victory the land seized by the peasants would be restored to its former rulers, and the lamentable failure to understand that in the anti-Bolshevist war politics and not military strategy must play the dominant role, were the chief causes of the White defeats. This theory is borne out by all the various White adventures … the course of each being, broadly speaking, the same. First the Whites advanced triumphantly, and until the character of their regime was realised they were hailed as deliverers from the Red yoke. The Red soldiers deserted to them in hordes and the Red command was thrown into consternation … Then came a halt, due to incipient disaffection amongst the civil population in the rear. Requisitioning, mobilisation, internecine strife, and corruption amongst officials, differing but little from the regime of the Reds, rapidly alienated the sympathies of the peasantry, who revolted against the Whites as they had against the Reds, and the position of the White armies was made untenable. The first sign of yielding at the front was the signal for a complete reversal of fortune.456

Taking advantage of his army unit being dispatched to the front line in September, Duke managed to persuade his commanding officer – who was a tsarist – to allow him to travel to Russian-occupied Latvia with two other soldiers rather than the rest of the regiment. When they reached Latvia, they jumped from their train and disappeared into the forest, joining thousands of other ‘Greens’ – soldiers who chose to be neither Red nor White, but avoided both factions by hiding in the forests. With secret documents concealed about his person, copied onto sheets of toilet paper, Duke finally reached safety.457

Meanwhile, the Russians were making progress against the White Russian and Estonian forces in and around Pskov, and on 10 August the Bolsheviks tentatively offered to recognise Estonian independence in return for a voluntary evacuation of Russian territory by the Estonian forces. This was, of course a welcome development for Estonia, but both the White Russians and the British opposed such a development. The British military attaché in Tallinn, Brigadier Frank Marsh, summoned both Estonian and White Russian officials to the British Embassy in an attempt to push through an agreement that would satisfy British support of both an independent Estonia and the White Russians. He informed the Russians that it was imperative that they formed a Northwest Russian government; this would then have to recognise Estonian independence – unless they did so, the Western Powers would no longer support them.458 Yudenich had little choice but to agree. However, it appeared that Marsh – and his superior, General Sir Hubert Gough, head of the Western Powers’ military mission to the Baltic – had greatly exceeded their authority in forcing such a recognition of Estonia; Kolchak was still refusing any such recognition, and many officials in London were furious about the developments in Tallinn. Meanwhile, Russian troops recaptured Pskov on 8 September.

Politicians from all three Baltic States met in Tallinn on 14 September, where they agreed that they would negotiate for a collective peace with Russia. Formal talks with the Estonian government began on 16 September in Pskov, but were broken off after two days.459 Part of the reason for this was that the Baltic States had attended a conference in Riga on 26 August, where they met representatives of the Entente Powers. Here, they were urged to support a planned attack by General Yudenich; clearly, supporting such an attack would not be possible if they were actively negotiating a peace settlement.460 But, given what had been agreed in Riga, it seems odd that there was any point in meeting the Bolsheviks in Pskov. Perhaps it was intended to mislead the Russians; perhaps it was an indication of different factions within the Baltic States pursuing different agendas.

On 10 October, Yudenich launched his Northwestern Army in an attack towards Petrograd. He had spent the months since his previous attack increasing the size of his force; it now numbered over 18,000, with artillery support and two armoured trains. His force even included six British tanks, crewed by British volunteers. The forces opposing him were numerically greater, but were severely handicapped by poor supplies and chaotic organisation.461 He had tried to secure Finnish support for the attack, but although Mannerheim was in favour, the Finnish president, Kaarlo Ståhlberg, refused permission. Admiral Kolchak, who was nominally the leader of the White Russian cause, had previously refused to recognise Finnish independence from Russia, and Yudenich’s somewhat belated assurances that he would ensure recognition of Finland were in vain.

At first, the attack of the Northwestern Army enjoyed considerable success. The Bolshevik forces were now under the command of Trotsky, Stalin having returned to Moscow. The contrast between the leadership of the two sides could not be greater; Trotsky, the great orator of the revolution, inspired his fellow citizens to take up arms for the defence of the Russian capital, while Yudenich and Rodzianko squabbled about who should command the army in the field. From the moment they crossed the frontier, White Russian soldiers began to desert, even when they were advancing and winning battles. Some joined the Reds, but most were simply taking advantage of being on Russian territory to try to make their way to their homes. Kingisepp fell on 12 October, and, the following day, 1,600 Estonian troops came ashore near the fortress of Krasnaya Gorka. Despite fire support from Estonian and British warships, the attempt to capture the fortress failed, though fighting continued until the end of the month before the Estonians withdrew. On 20 October, the leading elements of Yudenich’s force reached and captured Pavlovsk and Tsarskoe Selo, on the southern outskirts of Petrograd.

At approximately the same time, the White Russian forces under Denikin in southern Russia were making good progress and it seemed as if the Bolsheviks might be overthrown. Yudenich was aware of the fragility of his army and the numbers of desertions it was suffering and was anxious to reach Petrograd as soon as possible; however, he was also aware that if he were to reach and capture the Russian capital, he would then inherit a huge problem. The city was close to starvation, and whoever controlled it would be responsible for finding sufficient food supplies to prevent a mass uprising. Hoping that the British and others would be able and willing to come to his aid, he ordered his troops to press on as rapidly as they could. Even Lenin began to consider abandoning Petrograd, but Trotsky had no intention of allowing any such thing. He insisted that the cradle of the revolution could be turned into a fortress, in which every house would be a strongpoint and the White forces would be bled to death. Critically, the rush by Yudenich’s troops to reach Petrograd included a division that had actually been ordered to march to the southeast of the city in order to cut the railway line from Moscow. With this vital supply route intact, the Bolsheviks were able to bring up substantial supplies. On 21 October, a Bolshevik counterattack recaptured the southern suburbs of Petrograd. The Fifteenth Red Army drove up from the southeast and attacked towards Volosovo, threatening the supply lines of the Northwest Army. Heavily outnumbered, Yudenich had no option but to withdraw towards Estonia. On 15 November, his troops retreated from Kingisepp, abandoning their last major possession inside Russia. As they fell back, they encountered villages and towns full of White Russian supporters, who had intended to follow them into Petrograd:

Every village, every house and every shelter of any sort were literally overflowing with miserable, hungry, freezing people. There was not a single sheltered corner where the retreating soldiers could warm themselves and rest. The fighting men therefore had to live without shelter during days and nights when the temperature was 10–18 degrees below zero.462

Yudenich intended to withdraw to Estonia and regroup, but the Estonian government had no intention of allowing this. As the White Russians reached the border, most were disarmed. The official reason was that Estonia did not wish to allow such a large well-armed body of demoralised men to wander within Estonia; another explanation is that the Bolsheviks had offered to recognise Estonian independence in return for bringing the war to an end.

For Yudenich, this was the end of his attempts on behalf of the White Russian cause. He was placed under arrest by the Estonians but was released after pressure from Britain and France. He left the region and made his home in France, where he avoided involvement in White Russian circles. He died near Nice, in 1933. He left behind him the disarmed men of the Northwest Army who spent a terrible winter finding whatever shelter they could. Thousands died of starvation and disease; a few of their officers managed to travel to join White forces elsewhere, but for most it was enough to find a way out of their predicament. Many drifted back across the border into Russia and made their peace with the Bolsheviks, returning to the homes they had left many years before. Others made new homes in other parts of the world; few were allowed to settle in Estonia.

The Soviet forces that had pursued Yudenich’s retreating army now attacked towards Narva in an attempt to seize the city as a final bargaining chip in the peace negotiations. The Seventh Red Army made some initial gains, but was forced to halt at the end of November to regroup. Peace talks opened on 5 December in Tartu, and, hoping to exert leverage in these negotiations, the Bolsheviks renewed their attack on 7 December, with the Fifteenth Red Army joining the assault nine days later. After breaking through the Estonian lines, the Russians crossed the frozen River Narva south of the city, but the following day the reinforced Estonian 1st Division counterattacked, slowly driving the Bolsheviks back despite suffering heavy losses. In the peace negotiations, the Bolsheviks suddenly made a surprise demand for a strip on either side of the Narva to be kept free of fortifications; when the Estonians refused, they made a final attack on 28 December. By the end of the year, exhaustion and snow brought all combat operations to an end, and the Bolsheviks dropped their demand.

A ceasefire came into effect on 3 January 1920, and the Treaty of Tartu was signed on 2 February. The treaty specified the border between the two nations, with a strip of land to the east of Narva remaining in Estonian control, and allowed for movement of displaced Russians and Estonians to their homelands. It also included a renunciation of any Russian claim to Estonian territory and a transfer of gold from Russia to Estonia, representing Estonia’s share of the gold reserves of the Tsarist Russian Empire. For both sides, this treaty represented a significant landmark. For Estonia, it amounted to a ‘birth certificate’ for the nation, while for Lenin’s Russia, it was the first treaty agreed with a foreign power. Estonia had gained her independence, but at a substantial cost: military casualties in the war were estimated at over 3,500 dead and nearly 14,000 wounded. In addition, Narva had suffered substantial damage, with many civilians killed or wounded. Nevertheless, the nation could look forward to a new future.463