HOLLYWOOD AND the writer: so the first thing that happened was I had this successful book of short stories called In the Land of Dreamy Dreams. That same year the twenty-five-year-old daughter of a friend in Jackson, Mississippi, won a Pulitzer Prize for a play. She was out in Hollywood turning down offers as fast as she could answer the phone, so she told one of the producers at Twentieth Century Fox to call and offer one of the deals to me. Deals, that’s what they call them out there. It reminds me of my brother and me matching nickels with our lunch money in the sixth grade.

I was in my kitchen in Fayetteville, Arkansas, one afternoon in 1980 and the phone rang. It was a businesslike voice calling from Hollywood and offering to give me sixty-five thousand dollars to rewrite the Italian film Wife-mistress and set it in New Orleans. You’ve got to be kidding, I said. Why on earth would you want to do something like that?

That was before I knew you are supposed to say, Oh, yes, what a marvelous idea. How did you ever think up something so wonderful? That is the proper response to a Hollywood producer. Oh, my, what a wonderful brilliant idea. Gee, I’m honored you called me in on that. Besides, I didn’t know anything about publishing or movies at the time and I thought sixty-five thousand dollars must be some magic number of dollars they gave away right and left. I had just been offered almost exactly that amount of money for something else someone thought up for me to do. I didn’t know yet that all you got to begin with — up front, they call it — was a very small amount of money and you had to work for months or years even and then it was highly unlikely that they would ever give you the rest of the money. Also they make you feel like it’s you who has failed, never that it was they that couldn’t pull the deal off — Hollywood is really as sleazy as it’s reported to be. It chews up writers and spits them out. It wastes their time and their dreams.

I didn’t know any of this yet. “Well, listen,” I told this producer, trying to make her feel better about coming up with such a dumb idea, “I’ve got a lot better ideas than that for making movies.” Oh, she said, tell me. So I told her the entire plots of about three movies and even called her back on my own money to finish one I had to interrupt to go to the door. So she wrote that all down and I never heard from her again.

I found all of that very interesting. Later I had some more offers of about the same kind — I just kept turning them down. I am saving myself for something I can believe in — that’s how crazy I am.

UNIVERSITIES are always after me to give them my papers (by which they mean my letters and notes and worksheets). Whenever that happens I go out to the shed and get a sack of them and burn them up in the wood stove. I hate the idea of some poor graduate student down in a marble basement somewhere going through my notes and letters and wild imaginings. These pieces of paper are meaningful to me because any time I look at one of them it reminds me of what I was doing when I wrote it. But why should some stranger waste his time on my worksheets?

A poet told me a good one the other day. She said academics have a new name for a writer’s worksheets. They call them repressed papers. Here are some of my repressed papers. I found this notebook on the floor by the piano this morning. It’s been there for months.

To comprehend the major blueprints. An event occurs in three dimensions of space and one of time, or motion?

A four dimensional space time continuum. Is time motion? Yes, it seems so.

The simpler the premises the wider the area of applicability.

The heuristic view that light can be both wave and particle.

The questioning of causality. Always we have taken for granted the idea that every event could be explained by its antecedent conditions.

What is random?

DO THE LAWS OF CAUSE AND EFFECT GIVE WAY TO THE LAWS OF CHANCE AT THE ATOMIC LEVEL?

The equivalence of all inertial systems in regard to light.

Inertia. The tendency of a body to resist acceleration. Light is composed of discrete packets or quanta which move without subdividing and which are absorbed and emitted only as units.

Light is composed of quanta.

The study of the very small is quantum physics and the study of the vast realms of space is relativity.

I will name the new book Light Can Be Both Wave and Particle. In memory of Everything That Rises Must Converge. Remember how that title haunted me and how hard I tried to know what it meant? Yes, Light Can Be Both Wave and Particle.

“Wave and particle?” my editor said and shook his head. “Why not, it suits me if it suits you.”

MORE REPRESSED PAPERS:

I would still be a writer whether or not I had ever been

in psychoanalysis but I would be a different writer,

more driven, frightened, wild and unsure, a poet hiding

behind the mask of poetry, talking in riddles,

obsessed for days with words like riddles,

caught in traps of language,

unable to understand the sources of language or my own

subconscious motivations and drives.

I would not know as much, maybe.

Maybe I found out as much writing as I did talking.

Psychoanalysis is the impossible profession. The terrible paradox is that the knowledge gained by psychoanalysis is not of much use in the real world. No, that’s not true. It’s of use to a writer. The terrible problem is that the knowledge is not transferable.

My Freudian said I was not in analysis. I would never lie down on the couch. I sat cross-legged on the floor looking at his shoes. He would never let me touch his shoes. Anyway, I think I am funnier and wiser and more balanced because of it. I like myself more and trust myself more. Of course, I might have been that way because I got older. Or maybe it’s just because I’ve gotten up every day for eight years and done my work and am still doing it. Maybe my work healed me of the small amount of civilizing I was exposed to. Guilt is too high a price to pay for civilization. There’s got to be a better way.

I was sitting on a bed in a New York apartment arguing with my cousin about God.

“Who made you?” she demanded.

“I don’t know.”

“You think you’re so powerful you made yourself?”

“I didn’t say that, Baby Gwen, you said that, don’t put words in my mouth.”

“Then what do you believe? Even you have to believe in something.”

“I believe that man takes his own goodness and sets that intelligence outside of himself and calls it God and worships it. And then he takes his natural ability to transmit thoughts and he calls that the power of prayer. It’s all semantics. It’s all words.”

“You have to make the leap of faith. Someday you’ll do it.”

“I will not.”

“It’s all faith. It’s faith and grace.”

“It’s twelve o’clock, Baby Gwen, and we’ve been arguing this for thirty-seven years. I’m going home.”

We get up from our mutual great-great-grandfather’s bed which my cousin keeps in an apartment in New York. We hug and kiss and go our separate ways.

I walk out into the streets of New York City at night. Lights that man invented and made out of his greatness are all over the place on the streets and above. Through a crack in the skyscrapers are other lights, wildly, crazily dependable somehow or other in case it is true that the earth is round and moving on its axis among the stars.

I KNOW a lot of two-year-olds that have genius. They are terribly observant, absolutely curious, willing to take risks. They will pay endless attention to detail, will return over and over again to a problem until it’s solved. Suddenly, they make the final move, the cap is off the bottle, the cabinet is open, the door is unlatched. My children were escape artists. They ran away to have adventures. I have chased them through the streets a million times, in my nightgown or in the rain. The oldest one was the best at it. When I found him he would be sitting in some stranger’s house eating cookies. He knew how to pick his victims. They would usually be people about the age I am now. Do you remember how marvelous a stranger’s house smelled when you were small? That’s another mark of genius, the senses are keen and finely tuned.

How to hold on to that native genius and also learn the things we need to know to survive. How to hold on to the breadth of genius and still narrow it down enough to concentrate on one piece of work. How not to allow the narrowing to become more important than the whole. These are big problems. I’m thinking about them all the time. How not to let the world de-genius us, our children and our grandchildren and our friends.

Here’s one thing I know for sure — you have to stay flexible. You have to have a lot of possible moves so no one can get you in a position where you think there’s only one way to live or only one way to solve a problem. A Jungian I know used to make me so mad telling me a story over and over about a friend of his who refuses to eat in the same restaurant twice or drive the same route to work in the morning. Oh, I know, I would say when he told me that story. You’ve already told me that, don’t tell me that again. No, he would answer, hear me, you aren’t listening. Then he would tell it to me again. It was a long time before I began to see the wisdom of that story. Every time I would do something like take a different path when I walked downtown, I would say, Oh, my God, this is so silly.

It is silly. That’s the point. It’s divine and silly. It’s the stuff that genius lives on. To constantly sample the riches and variety of life. Watch a child move from one activity to the other, moving around a house, never exhausting the possibilities of any one thing before moving on to the next one. We say of children, they are into everything. We should be into everything. We should get up one morning and take all our books and put them in a pile in the middle of the floor and start playing with them. Euripides and Aeschylus and Hemingway and Thornton Wilder and Margaret Mead. Faulkner and Edna Millay, and oh, yes, The Conquest of Mexico and The Conquest of Peru which I borrowed years ago from my ex-husband. Maybe I’ll mail them back to him for his birthday.

I AM GEARING UP to go to New York for two weeks to oversee a professional reading of my play. It is a play that I began in New York in February of 1984. I began writing it during the first act of Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love. I wrote all over my program and my agent’s program. Then I went home through a blinding New York rainstorm and wrote all night in a hotel room. The next day I had lunch with my agent and told him I’d been up all night writing a play.

I told him the story, then I put the play away for three months. In June I had to go to Lincoln, Nebraska, to teach for a few weeks so I took the notes with me and there, in a basement apartment near the campus, I hammered out three full acts in less than a week and sent it to a typist.

Since that time the play has undergone four major revisions, elaborating and extending what is there, taking stuff out of the stage directions, which at one time contained a lot of the best material, and putting it back into the play. I am, after all, a fiction writer not a playwright and had to transpose the work from one form to the other.

Now, the American Place Theatre is going to have a professional reading of the play with a fine actress playing the lead. I’m excited and scared, but the day I no longer do anything that frightens me and makes me shy I will know I am finished as a writer. And of course I’m hoping that around eleven o’clock one night they will say, “Oh, Ellen, you have to rewrite the second act,” and I’ll say, “Don’t worry, I’ll do it tonight,” and so forth. I’ll emerge from a hotel room the next morning holding a brilliant revision and everyone will cheer. I keep thinking about a passage from a book by Georges Simenon.

“Why do we read?” he asks, “why do we go to a show? Imagine an entomologist, an observer of insect life, suddenly witnessing the exodus of a quarter of the inhabitants of an anthill, at a time of day when they normally would be sleeping. They are going off to a mysterious appointment. He sees them jostling each other and converging towards a clearing where the soil rises in tiers. In order to enter that enclosure each ant must surrender part of his winter provisions to a sharp-eyed official.

“Why have they left the shelter of the anthill and undertaken this long march? What are they waiting for, motionless and quivering with their gazes turned to a small circle of earth?

“Imagine the shock to our entomologist if he saw five or ten ants, no different in any way from the others, move forward into the light and amidst an almost religious silence, begin to mime a scene from the life of the ants.”

A FRIEND of mine had dinner with the president of a large makeup company the other day. It’s all fear, the president told him. That’s our key word. Keep them afraid that no one will love them and you can sell them anything.

I have pondered this little story. Several years ago I became angry at a friend for questioning a column I wrote for Southern Living magazine. “Puss,” he said, “what’s going on? What’s happened to you?” “Nothing,” I replied, getting really mad at him. “It’s just a magazine article, that’s all.”

The article was about how I’d gone down to Jackson, Mississippi, to visit my mother and as soon as I got off the airplane she told me I looked like Daisy Mae. I was wearing a short denim skirt and leather sandals and a cotton shirt tied around my waist. Actually, I looked just fine. My hair was long and loose, my skin was clear and the color it turns all by itself in the sun. I looked about as good as I can look.

By week’s end I was a different person. Jackson, Mississippi, had done a number on me. I had reverted to type, turned myself back into a frightened sorority girl. I had bought a lot of useless clothes and spent two hundred dollars on makeup and ruined my hair with a permanent.

The magazine article I wrote about all that left the reader with the impression that I thought it was very funny. A lipstick costs eight dollars this year. You have to do a lot of work that someone else thinks up for you to afford that kind of fear.

SUMMER IS THE TIME to deal with paradoxes, with questions that have no answers, problems that can only be surrounded, laid siege to. The Castle of Fat is such a problem. The Castle of Fat is surrounded by a moat of self-deception and absurdities. High walls of fantasy surround it. Evil guards of self-hate man the towers. In the square is an everlasting spring of Diet Coke from which the inhabitants draw sustenance.

Some of my friends and I have set out to besiege the castle. First of all we have to decide whether we are fat or not. I was in conference one afternoon recently with a philosopher and a retired United Airlines pilot. We had been for a long walk around the mountain. Afterwards, we were in the philosopher’s kitchen and we were talking about fat.

“I don’t know if I’m fat or not,” I said. “That’s what plagues me. I might not even be fat. I might just think I’m fat.”

“The brain has to have glucose,” the pilot said. “That’s a fact.”

“The part I hate,” the philosopher said, “the part I cannot deal with, is that a grown man would take off his underpants to weigh himself.”

“Correct,” the pilot agreed. We sank our chins deep into our hands to think it over.

“Why do you think you’re fat?” the pilot asked.

“Because I can’t button my skirts,” I replied.

“That sounds fat,” the philosopher said.

“You could get another skirt,” the pilot suggested.

“Stay for dinner,” the philosopher’s wife put in. “We’re having meatloaf and mashed potatoes.”

This issue has reached crisis stage in the United States. I know the way I’m thinking about this problem has been imposed on me from without. I can’t stand to be dumb and brainwashed about the structure and size of my own body. We will be having further meetings about this matter and I will be giving you reports. One of my characters once said, “I think maybe it is my destiny to start a fad for getting fat.”

Then a good-looking carpenter goes by and she decides to wait a few more years before putting her plan into operation.

I’VE BEEN DRIVING along the Natchez Trace, “that old buffalo trail that stretches far into the past.” I‘m in Chickasaw County, Mississippi, near Cane Creek, moving turtles off the road and thinking about where I‘m going and where I‘ve been.

I‘ve been visiting my son Garth, the one that went off to Alaska when he was eighteen. Now he’s twenty-eight and he lives on a farm with his wife, Jeannie, and two dogs and three cats and twenty-six cows and five gray horses and two brand-new colts and one lonely guinea hen. There were six guinea hens but foxes killed them so Jeannie and Garth are down to one.

I drove all day yesterday to watch Garth with his animals and hide out from a lot of sad confused statements being made about me by Arkansas politicians.

I drove to Mississippi to watch Garth with his animals. All his life he has had a way with animals. He can hold out his hand and anything will come to him.

I needed Garth, to touch him and sleep under his roof. He lives in a trailer underneath six enormous oak trees. From his yard all you can see in four directions are fields and trees and skies. Last night the skies were so wonderful — no man-made lights for miles to dim the stars.

The seventeen-year cicadas hatched here last month. Jeannie says it was so loud no one could sleep at night. The guinea hen and the dogs went wild running around gobbling up cicadas like popcorn.

Back in Arkansas the newspapers are full of simplistic versions of a speech I made to the Arkansas governor’s school for the gifted and talented. The professional breast-beaters are coming out of the trees like locusts. All I did was tell four hundred fifty students that you had to be able to think for yourself to do creative work. I told them that to achieve that they might have to ignore authorities like their parents and teachers. I was in an especially generous mood that morning and I was trying to show them the full force of my creative self, the part of me that writes the books.

The next thing I knew I was headline news. Thank God for a free press. The stories are calming down and the reporters are printing my side, or as much as I can bring myself to say to defend myself against this tempest in a teapot.

For now, as I stop to write this, I am driving along the Natchez Trace saving turtles in honor of my son Garth’s childhood ambition to be the man who builds fences along country roads to save animals from getting run over. I’ve saved five turtles so far. I stopped one time to save a clump of dirt. A good-looking young man in a red sports car stopped to help me save the fifth turtle. If this was a movie I was making and the heroine was twenty years younger, I could have made something out of that.

I WAS TEN YEARS OLD the night the Japanese surrendered. It was night in Seymour, Indiana, although it was morning on board the ship where the emissaries of the emperor were signing the papers.

General MacArthur was there, wearing, I was sure, his soft cap and smoking his pipe. And General Skinny Wainwright, who surrendered on Corregidor and spent the war as a Japanese prisoner. If he was skinny before, now he was emaciated. Admiral Halsey was there, and Percival, the Briton who surrendered Singapore. Also, Englishmen, Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Russians, Chinese, and row upon row of American sailors in whites. The talks began. The speeches and translations. It meant my uncle would be coming home. He had flown bombers over Germany. Later, he flew with General Claire Chennault and the Flying Tigers. How strange that the youngest and gentlest of my father’s brothers should have been the one to drop the bombs.

We had worried about him night and day. Now the worrying was over. I was in bed with my mother and my father and the magic eye of the radio was glowing in the dark and we were listening to the Japanese surrender.

There was no dancing in the streets at 504 Calvin Boulevard in Seymour, Indiana. My parents were very quiet and serious. When I said, “Goody, goody, goody, we beat them,” my father said, “Be quiet, war is bad, beginning, middle, and end.”

I remember snuggling down into the covers, keeping my elation to myself. Goody, goody, goody, I was thinking. Now they can’t come over here and stick bamboo splinters up my fingernails and make me tell everything I know. I had worried myself sick during the war about whether I could stand up under torture. I was afraid they would give me truth serum or the pain would become too great and I would break.

The speeches and translations went on. It was dark in the room but there were stars outside the windows. No more air-raid practices with drawn blinds. Seymour, Indiana, was safe and I could cash in my war bonds. There would never be another war. We had the biggest bomb ever made and no one in the world would ever dare make war on us again. We would divide up the world with Russia and they would run half of it and we would run the other half. Truman and Stalin and Winston Churchill and Ike and General MacArthur would run things and everybody would be happy and have a good time.

The ceremonies ended. “These proceedings are over,” General MacArthur said. My father heaved a sigh. We turned off the radio and the magic eye dimmed and went out.

It was some weeks later that Jody Myerson’s father came home from the Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. He weighed about a hundred pounds. He looked so terrible I could hardly stand to walk by the house where he was recuperating. “He’ll be better,” my mother said. “In time he’ll be a whole man again.” But I had no faith in it. His eyes stared at me through the walls of the house.

I am marked by that war. To this day when I see a group of Japanese businessmen getting on an elevator in New York City I think of Jody’s father. I wonder what they think of when they see me stare. It is in spite of such knowledge that I dream of peace.

A LOT OF PEOPLE have gotten the idea that what I do for a living is sit around on a mountain writing a journal. I will answer that, although it is not my nature to explain myself or justify my actions. I do what I think is right and let people think what they please about it. I am not in the business of trying to make people understand my complicated and individual life-style.

What I do is write prose fiction, I write it six or seven hours a day, seven days a week, except for the times when I force myself to stop writing in order not to completely lose touch with the real world. It is easy for me to isolate myself and write books — the hard thing is to live in a real world with other people’s needs and desires and dreams. I’m a good receiver — I hear it all.

Anyway, I write for a living. It is an exciting and jealous obsession. One of the ways I fight the obsessive part is by making these journals — they are immediate — out of my immediate experience. Another thing I sometimes reluctantly do is give readings and lectures and very occasionally teach a few days at a college.

But none of this answers the real question. The real question is, How do I have time to write books when other people who wish to be writers don’t have time?

I tell students when I talk to them that the first thing a writer has to do is find another source of income. Then, after you have begged, borrowed, stolen, or saved up the money to give you time to write and you spend all of it staying alive while you write, and you write your heart out, after all of that, maybe no one will publish it, and, if they publish it, maybe no one will read it. That is the hard truth. This is what it means to be a writer. I wanted to earn the name of writer for myself and I went to work and did it. I am often awestruck at that fortunate occurrence.

WHEN LAST I wrote about fat, my friends and I were in the philosopher’s kitchen trying to decide whether it was wise and/or sane to be so irritated at the body’s natural desire to grow larger and to carry stores of food around on top of its muscles and bones. Stores that might come in handy if we lived in a less fortunate country, or if we were survivors of an airplane crash in the Andes or in case the weather should change and no longer favor the great farmlands of the United States of America.

My friends and I have spent many hours this past summer talking very seriously about losing weight. If it is intelligent to give in to the prevailing winds of fashion about how large our bodies should be or become.

How much of our so-called body image is fashion? we asked ourselves. Is it healthy to divest ourselves of pounds? If so, how many? How will we know when to stop?

I am the ringleader of the faction that says, Yes, we must diet. We must to go bed hungry and fit back into our clothes and never give in to inertia and complacence.

So I dieted all summer and in three months I had gained three pounds. Needless to say I do not think this is funny. I think it is very very cruel and unfair.

I was cheered up last night by being taken to hear a young sports nutritionist. She talked to us about food and how we use it and told us about the new studies in nutrition. Telling us a lot of very sensible things about how to become healthy and beautiful without starving ourselves. She kept stressing the importance of complex carbohydrates and exercise and laying off of sugar. The thing she said that cheered me up was that nutritionists are very leery nowadays of people weighing themselves all the time.

We are diverse and wonderful creatures made of starlight and comet dust. What shape and size our individual bodies take cannot be measured by steel scales and weight charts. We are breathing oxygen created by plants on a planet hurtling through space. We are not a flat image in a mirror or the reflection of a starving model in a fashion magazine. Life is soft and round and generous.

Some of us may be underexercised and over-guilt-ridden but we are not fat. We are wonderful and mysterious and can swim in water.

I WAS TALKING to a reporter the other day and she asked me if I thought my studies in philosophy had affected my writing, shaped the forms I chose to write in. I told her that I didn’t separate knowledge into genres or categories because it seemed to me that all of us were probing the same mystery, coming at it from different angles, calling it different things, but all asking the same questions endlessly. Who am I? Why am I here? What are we doing? Is there free will and, if so, how much, and who has it? The scientist and philosopher René Dubos explores these questions with great intelligence and humor. On free will he quotes Samuel Johnson, who said, “All scientific knowledge is against free will, all common sense for it.”

I do not understand why I write fiction when the main things I read are books about science and philosophy. Perhaps I think that by exploring character and event I can create actors to act out the questions I am always asking. I have a character named Nora Jane Whittington who lives in Berkeley, California, and who has so much free will that I can’t even find out from her whether the twin baby girls she is carrying belong to her old boyfriend, Sandy, or her new boyfriend, Freddy Harwood. I can’t finish my new book of stories until Nora Jane agrees to an amniocentesis. She is afraid the needle will penetrate the placenta and frighten the babies.

I created Nora Jane but I have to wait on her to make up her mind before I can finish the title story of my new book. This is a fiction writer’s life. Fortunately, I am going to be in California soon and I will drive up to Berkeley and walk around some of Nora Jane’s old hangouts. By the time I get home maybe I’ll know what to write.

Now I know the answer to the reporter’s question. The effect that studying philosophy has had on my fiction writing is that I know that someday I will get to sit down and write a book about Free Will Versus Determinism and the only character will be me.

IN ORDER to be a writer you must experience and learn to recognize and cope with periods of what Freeman Dyson calls stuckness. In order to do creative work in any of the arts or sciences you must go through long or short spells of not knowing what is going on, of being irritated, and not being able to find the cause, of being willing to work as hard as you can and what happens isn’t valuable enough, isn’t good enough, isn’t what you meant to do, what you meant to say. Then you just have to keep on working. Then, if you can bear it, if you don’t quit and move to Canada or call up Joe and go hiking for two weeks or quit your job or get a divorce or do anything else to relieve the pain, and it is pain, it’s really irritating, it puts you in a bad mood, you are irritable to children and can’t focus on anything and keep changing your mind, if you can put up with it and just go right on sitting down at that desk every day no matter how much it seems to be an absurd and useless and boring thing to do, the good stuff will suddenly happen. It may be twelve o’clock at night when you’re doing something else or are in the bathtub. It will be when you have given up and least expect it. There it will be, the radium, the formula, the good short story, the real poem.

I have the wonderful feeling that I understand this right now, because last night at ten o’clock a two-month stuckness broke and gave me the best new story for my new collection. I had been reading a book called The Sphinx and the Rainbow. A wonderful book about the right and left halves of the brain and the frontal lobes. Very clear stuff about how the mind creates the future. How it marshals its forces and then goes to work at its own speed and in ways we cannot always comprehend until the thing is finished. Very rich stuff. I recommend it for anyone, but especially for anyone who is currently stuck.

MY EDITOR has been here and we put together a book of stories. There are thirteen of them. A very slim volume. Thirteen out of twenty were good enough to keep. There is a story that didn’t make it called “The Green Tent” about a little boy and his grandmother who travel all over the universe in a tent. I’m sorry I had to give that one up. I really liked that story.

Hemingway said one of the great problems for a writer is deciding who his audience will be. Do you write for the reviewers, terrified they will call something cute or sentimental? If they manage to scare you enough you will get to the point where you are afraid to write about anything really human, like passion or love. People are endlessly fascinated by love. They talk about it and laugh about it and desire and hate it. Whenever one of us falls in love our friends watch it as they would the progress of a disease.

So I have written a book of stories called Drunk With Love in which I set out to explore what I know about the subject. I have failed. Not failed as a writer. But I have learned nothing about love and added nothing to our store of understanding.

“All is clouded by desire, like a mirror by smoke.” I thought I was going to penetrate that mystery through my characters. Wrong. All I did was wade deeper and deeper into the mystery. In the end I let the last words of the book be spoken by Nora Jane Whittington’s unborn babies.

“Let’s be quiet,” Tammili said. “Okay,” Lydia replied.

God bless my editor. He let me keep that in.

“What are you going to do now?” he asked, when we had finished our work.

“I think I’ll go fall in love,” I answered.

“Why don’t you just go home and stick your finger in an electric wall socket instead,” he suggested. “It would save you the trouble of getting dressed up.”

He’s right. I’ve changed my mind about going to stick my finger in the electric wall socket of love. I’m going down to New Orleans instead and get my grandchildren and go riding around in my little blue car pretending we are space cadets. I’ll let someone younger and braver than I am sit around the house waiting for the phone to ring.

I RECENTLY SAW a wonderful sight. I was driving back from New Orleans and stopped in Pass Manchac, Louisiana, to see how things looked now that the flood waters had receded. Pass Manchac is a famous place on the Bonnet Carre Spillway across from New Orleans. It is a small fishing village that was several feet underwater in the October floods. I saw it then with water all over the floors of the houses and men walking along the railroad tracks carrying sandbags, still trying to save what could be saved.

Anyway, the flood was several weeks ago and I stopped by to see how things were going and went into Sykes’ grocery store and talked to the proprietor and had some doughnuts and bought a tablet and a pencil. The tablet was slightly mildewed on the edges. The proprietor told me about filling the sandbags, who all was there and who came to help and we discussed how resilient men and women are. Then she turned around. “Oh, look at this,” she said. A great mountain of a man was coming in the door. A beautiful tanned man with white hair leading or being led by two small children. The proprietor told me that the smallest one had been abused so badly he had to be in a full body cast for six months. “That’s their foster father,” she said. “He’s got them now and they’re okay.”

They were beautiful children. They came into the store and got some candy and went to the back to find life preservers as they were going out on a boat for a Sunday outing.

“Hold me,” the small child said, as soon as he saw me looking at him. I picked him up in my arms and held him there. “We’re getting to adopt them in February,” the big fisherman said. “It’s all set.”

“Oh, that’s great,” the proprietor said, and for a moment I had a sense of sharing the community of Pass Manchac, a fishing village where people know each other and are involved in each other’s lives and stories.

I am haunted by these events. For many miles down the road, I was filled with a sense of elation. The story of mankind is not written in the occasional crazy parent who will harm his own child. The story of mankind is the big fisherman who comes along and sets things right … the physicians and surgeons and nurses in some emergency room who are working the night shift and are there when the broken child arrives and put him back together and the fisherman who gathers the child into his life and goes to work to love him and the proprietor who cleans up the store after the flood and sells me a slightly mildewed tablet at half price to write this on.

I AM COMPELLED to write about this even though it embarrasses me to keep talking about my grandchildren. Still, this is supposed to be a writer’s journal and if there is one thing I’ve learned about writing it is to follow your compulsions.

Here is what I am compelled to write about today.

I have been alone for thirty-eight hours with two small children and no car. I have been locked up in an apartment with a four-year-old boy and a one-and-a-half-year-old girl and I am here to report that taking care of small children is the single most exciting, complicated, difficult, creative, and maddening job on the green earth.

Finally, I called for help. That famous seventy-seven-year-old child-worshipper I have told you about, my mother, is only ten blocks away, so I called and invited her to come pick us up and go with us to the mall to buy some winter clothes for the children. She’s always up for a good time so she came right over and got us and we went to the store. I had it in my mind to buy them some socks and jackets and something nice to wear in case we got invited to a party.

Ellen on sleeping porch, Hopedale Plantation

Ellen on Dixie, friends

Ellen and Dooley, 1939

Hopedale Plantation, built around 1905

Ellen and mother, 1939 or 1940

Friend, Dooley, Ellen, Aunt Roberta Alford (Indiana during war)

Ellen and Dooley

Ellen visiting in New Orleans, taken in booth in French Quarter, summer of 1948

Cynthia Jane Hancock (Ellen’s best friend) and Ellen outside Horace Mann School in sixth grade. Early spring, Harrisburg, Illinois

Mother, Ellen, Father, Dooley, 1939

Ellen, 1950

Ellen, seventh grade

Ellen at Columbia Military Academy dance, Columbia, Tennessee, 1951

Ellen at Chi Omega house dance at Vanderbilt or University of Alabama or Southern Seminary

Purple Clarion staff, Hartisbutg High School, 1950. Ellen as feature editor

Mack Harness, Ellen, 1984

Ellen at Mardi Gras, 1976

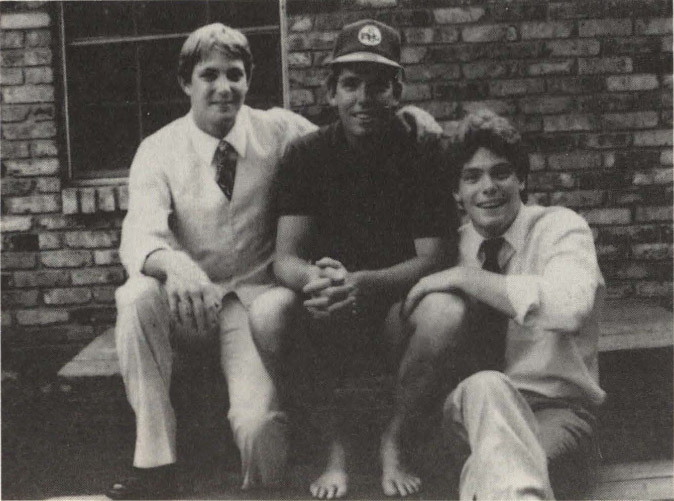

Ellen’s sons at her fourth wedding

Ellen’s sons: Marshall Walker, Garth Walker, Pierre Walker

Rosalie Davis, to whom In the Land of Dreamy Dreams is dedicated

Two and a half hours later the four of us emerged from the mall and began to search for the car. “I’m too old for this,” the child-worshipper said. “This is one generation too many.”

We had purchased a pair of Superman pajamas with a Velcro cape and a package of T-shirts that might someday fit someone and we had left a children’s department in tatters. Only the unbelievable patience of a saleslady named Laverne had made it possible for us to purchase anything.

The child-worshipper took us home and declined my invitation to come in. Later, I allowed the four-year-old to watch a Care Bears movie four times in a row — and that after all my tirades against children watching television. It was a movie called The Care Bears in the Land without Feelings. By bedtime he had mastered all the parts and had chosen for himself the role of Professor Coldheart. “THAT’S WHAT YOU GET FOR BEING SO TENDERHEARTED,” he kept telling me. “SO MUCH FOR LOVE AND TENDERNESS AND LITTLE FUZZY WUZZIES.”

The sun fell below the horizon. We had some cereal and milk. We dressed for bed. The child-worshipper called to see how we were getting along.

“How’s it going?” she said.

“How did I do this?” I said. “How did I do this day after day?”

“You weren’t very good at it,” she answered. “It never was your long suit.”

HERE IS my Christmas carol.

The best thing that has happened to me so far this holiday season was a discussion I had at the drugstore with two women who work there. The three of us decided that there was no way we were going into debt for Christmas. No way we were going to wake up on January first with a lot of bills to pay. God bless you, Merry Gentlemen, sell this plastic junk to someone else. You won’t sell it to Libby and Darlene and me.

“What do you want for Christmas?” I asked Libby as I was leaving. “I want grocery stores and drugstores to stop putting candy by the checkout counter,” she said. “So children scream for it while their mothers wait to pay. What do you all want?”

“I want folks to stop selling dope to kids,” Darlene said. “My doctor at the clinic, he’s got his only son locked up with his brain dead from taking dope. My doctor was crying when he was seeing me. Imagine that.”

The three of us hung our heads over the idea of anyone selling dope to children. We Three Kings of Orient Are. Three wise women at the Katz & Bestoff Drug Store.

Well, this is the saddest time of year and everyone knows it. Adeste Fideles. O come, all ye faithful. Everyone suffers the winter equinox, the death of the year. Everyone knows the sadness of Christmas afternoon after the presents are opened and the dinner eaten and there’s nothing left to do but pretend you had a good time.

One Christmas, I stayed all alone on a mountain and didn’t eat anything all day while Christmas went on below me. I was the Grinch of Christmas and it was one of the best days of my life. I wrote the last chapter of a novel and wouldn’t even answer the phone.

You’ll lose all your fans if you start knocking Christmas, the voice of bah humbug cautions me. Not my readers, I answer. My readers are literate people who can think for themselves. They are people who write me letters I like to read and tell me things I want to know.

So here is a Merry Christmas to all my friends and all the people who have helped me make these essays by doing the things I wrote about, and to all the little children screaming and crying for candy at the checkout stands and to all the parents who give in and to all those who say no.

I WENT TO the inauguration of the Radio Reading Service for the Blind and Print Handicapped Citizens of the state of Mississippi. There was a party at ten o’clock in the morning in the Mississippi Public Broadcasting studios and most of the writers in the state were there to start things off by reading from their books. This is a service that will go out day after day to all those who cannot see or are unable to hold a book or turn a page.

It was a bright January morning and everyone looked grand in winter suits and dress-up dresses. The director and manager of the service were there, looking properly nervous and excited. There was an opening ceremony with members of the legislature and doctors and lawyers and actresses and other volunteer readers. There was fierce competition for those spots. Mississippi is not a state where a chance to be on stage is taken lightly.

After the ceremony we all trooped over to the studios and the recording sessions began. Eudora Welty led off with her haunting and beautiful story “A Worn Path.” The rest of us were in the anteroom listening on a scratchy desk radio. The minute Miss Welty’s soft enchanting voice came on the air things changed in the room and the magic of storytelling was upon us.

“It was December,” she read, “— a bright frozen day in the early morning. Far out in the country there was an old Negro woman with her head tied in a red rag, coming along a path through the pinewoods. Her name was Phoenix Jackson. She was very old and small and she walked slowly in the dark pine shadows, moving a little from side to side in her steps, with the balanced heaviness and lightness of a pendulum in a grandfather clock.”

Miss Welty was followed by Willie Morris and Ellen Douglas and Gloria Norris and Richard Ford and Luke Wallin and Charlotte Capers and Carroll Case and Felder Rushing and Patrick Smith, some on tape and some in person. In the midst of this excitement a troop of sighted sixth-graders passed through the room with a string of blind and print-handicapped fifth-graders in tow. They were being led by a wonderful-looking little redhead in a plaid dress. She weaved her way in between Eudora Welty and Ellen Douglas and a pair of senators. “Excuse me,” she said. “Excuse me, please,” and led her charges back to tour the studios which would produce the books they would be hearing.

In a world of television watchers it is nice for a writer to know there is an audience who still needs words unaccompanied by pictures other than the ones they make up in their own minds.

SOME TIME AGO I decided to leave the secluded life where I wrote my books and go out into the world and see what was going on.

I spent two weeks on a reading tour. First I went to Boulder, Colorado, and read a story to the students and had a wonderful time walking around in the snow. Then I flew to Minneapolis-Saint Paul to read a story in the beautiful Walker Art Center. Outside, only a few blocks away, seven hundred volunteer workers were putting the finishing touches on the Ice Palace. In the dead of winter, in one of the coldest cities in the world, seven hundred grown men and women have cut blocks of ice out of a frozen lake and built a palace one hundred and twenty-eight feet high.

Minneapolis is always full of wonders for me. The Walker Art Center was showing the fifteen-and-a-half-hour film, Heimat, by the German director Edgar Reitz. It is one of the most beautiful movies I have seen in years. The story of a small German village and its inhabitants from the end of World War One to the present.

On Sunday, I flew home to Jackson, Mississippi, and changed suitcases and drove to Shreveport, Louisiana, to read a story to the officers’ wives at the Barksdale Air Force Base. Headquarters of the Eighth Air Force of the Strategic Air Command. I was taken on a tour of the base by two of the pilots’ wives. We went to see the sheds where uniformed men were standing on ladders working on the engines of the twenty-five-year-old B-52s and I marveled at the design of the KC-135s that fuel them in the air. I spent the day with the wives of the men who are keeping America safe. Their business is peace, they told me, and I believed them and thanked them for it.

There are many wonders outside the egocentric little cave where books are written. I have found out that the Federal Reserve system isn’t part of the federal government and now I’ve been to visit a SAC base. There’s no telling what will happen next.

WRITERS HATE to be questioned. It’s an almost superstitious feeling that it’s wrong to probe or analyze the muse. And yet, sometimes things come to light from questions.

In a question-and-answer session at the University of Colorado I found myself articulating something I have been suspecting for a long time.

How do you create characters? a student asked. How do you keep thinking up new people to tell your stories? I may not be able to anymore, I answered. I’ve been writing for about ten years now and I have created a cast of characters that are like a Fellini troupe. They are always trying to steal the spotlight away from each other.

It’s gotten to the point where it’s impossible for me to create new characters because the old ones keep grabbing up all the roles. The minute I think up a new dramatic situation, one of my old characters grabs it up and runs with it. Minor characters get up off the page and take the pen out of my hand and start expanding their roles. Scenes that have no business in the stories sprout like mushrooms as Freddy Harwood or Nieman interrupt stories to give themselves daring adventures or heroic moments.

In a way my characters are right. I can see their point. I have a responsibility to Freddy Harwood to let him tell his side of the story and not just leave him sitting in a hot tub with a broken heart.

Also, I am beginning to suspect there may be a limited number of characters any one writer can create and perhaps a limited number of stories any writer can tell. Perhaps that’s how we know when to quit and find something else to do for a living. I live in horror that I won’t know when to quit. I don’t want to be one of those writers who run out of things to write and then go around the rest of their lives talking about writing but not really producing anything anyone wants to read. When I’ve told all my stories and created all my characters I want to get off the stage as quickly as I can and with as much grace as possible.

SOME TIME AGO I had just finished a draft of a novel and left it in my typist’s tennis racket cover and then gone barreling down the highway leading south out of the Ozark Mountains.

I was driving down the highway eating powdered doughnuts and stopping every now and then to write things down. At the end of that journal entry I realized it was an illusion that the novel was finished and I knew very well it would take several more years and two or three more drafts to finish it.

Now I am working on it again. The Anabainein, I call this strange creation. A going up, a journey to the interior. It is a novel set in Greece during the Peloponnesian Wars. My pet book, based on a story I made up when I was a child. My mother loved the classics and filled my head with stories of the Greek pantheon and the glories of fifth-century Athens, and I made up a story about a slave girl who is raised by a philosopher and allowed to learn to read and write.

All these characters, all this research, all these pages and pages and pages. Perhaps it will be the best thing I have ever written. Perhaps the worst. Still, I have to finish it. A poet once told me that the worst thing a writer can do is fail to finish the things he starts. It was a long time before I knew what that meant or why it was true. The mind is trying very hard to tell us things when we write books. The first impulse is as good as the second or the third — any thread if followed long enough will lead out of the labyrinth and into the light. So I believe or choose to believe.

The work of a writer is to create order out of chaos. Always, the chaos keeps slipping back in. Underneath the created order the fantastic diversity and madness of life goes on, expanding and changing and insisting upon itself. Still, each piece contains the whole. Tell one story truly and with clarity and you have done all anyone is required to do.

I AM SPENDING the winter thinking about money. About money as a concept, an act of faith, a means of conveyance. Also, I am thinking about plain old money, the kind we are greedy for and think will solve our problems. Maybe it will solve our problems. It gives us the illusion of security. Money in the bank, a nest egg, something to fall back upon. Yes, I am going to ask money to forgive me for all the nasty things I’ve said about it.

I began my study of money by watching “Wall Street Week.” I started watching it for a joke. It amused me to see how happy and cheerful the people on “Wall Street Week” always are. No underweight actors and actresses begging the audience for love. Not this bunch. These are well-dressed, normal-sized, very confident people. All will be well, “Wall Street Week” assures me. The market goes up and the market comes back down, but after all, it’s only a game. The great broker in the sky smiles benignly down on his happy children.

Why not? I began to say to myself. Who am I to sneer at all this good clean fun? So I bought some stocks and now I really have a reason to watch “Wall Street Week.” Figures appear on the screen, bulls and bears made their predictions. Bulls and bears. Now I know what that means. Bulls are good things that mean I’m making money. Bears are bad things that mean I’ve made a bad mistake.

To paraphrase a poet, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rises and falls and thy name, O God, is kept before the public.

What a wonderful new obsession. At last I understand capitalism. At last my father and I have something to talk about. Once, years ago, my father begged me with tears in his eyes to take a course in the stock market. I agreed and signed up for a class. Alas, at the very first class meeting I fell in love with a redheaded engineer from Kansas and we went off into the night and never found time to come back to the class. Each age has its rewards. Once I had love and romance. Now I have the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the “Wall Street Week in Review.”

I HAVE BEEN OFF at a writers’ conference in Grand Forks, in the beautiful farmland of northeastern North Dakota. Where a fellow Mississippian named Johnny Little has just staged the seventeenth annual University of North Dakota Writers’ Conference.

Johnny is an old colleague of mine from a class Eudora Welty taught at Millsaps College in 1967. He was born in Raleigh, Mississippi, where he was the smartest boy in town. Then Johnny went to Millsaps and got even smarter. Then he went up to Fayetteville, Arkansas, to make a writer, as he calls it. Then off to North Dakota to teach. The winters were long and cold and he got so lonesome he started a southern writers’ conference, which turned into a national, then an international, affair. For seventeen years Johnny has been luring writers from all over the world up to Grand Forks to lend a hand in celebrating the spring thaw.

Edward Albee, James Dickey, Gregory Corso, Truman Capote, Susan Sontag, Jim Whitehead, Tom Wolfe, Joseph Brodsky, the list is long and illustrious. The University of North Dakota Annual Spring Thaw Southern and International Writers’ Conference. Not to be confused with the Raleigh, Mississippi, Tobacco Spit and Logrolling Contest, another of Johnny’s pet projects.

I had a good time being there but I never worked so hard at being a writer. It seemed to me I was being interviewed or questioned every waking moment by some bright young man or woman. I can’t even remember all the advice I gave.

To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee,

One clover, and a bee,

And revery.

The revery alone will do,

If bees are few.

That poem by Emily Dickinson was supposed to be the theme of the conference but the only time I heard anyone say anything about a prairie was a joke someone told about the flatness of the land around Grand Forks. Nothing to see, and nothing to get in the way of seeing it. I flew home down the course of the Mississippi River and then over to Shreveport, Louisiana, to address the Louisiana Library Association. If you are wondering how I am getting any serious writing done under these circumstances you are not alone. The dour old Scot who rules the roost in my subconscious is very suspicious when I tell him that seeing the world is part of a writer’s work.

HERE IS a writing lesson. I’m not much good as a regular writing teacher. I only know things as they happen, at the time they happen. If I knew them all the time I could get up every morning and write a masterpiece. The Greeks got up every morning and wrote masterpieces. Euripides wrote eighty-eight plays, of which nineteen survive. His fellow Greeks liked his plays so much that prisoners could gain their freedom by learning to recite them.

But this is supposed to be a writing lesson. Here is how I write a book. First I get a wonderful idea and I drop everything I’m doing and go and write it down and expand it as much as I can. Then I get very excited and go off and eat some ice cream or something I usually deny myself. Four or five days later I go back and read what I wrote and I decide it’s pretty good, but not as good as I dreamed it would be. A few days later the story or characters I began to create will begin to haunt me; they want another chance to show they are as wonderful as I originally thought they were and I go back into the story and begin to work on it. Work means exactly that. Hard thinking and hard attention and walking around the house with the telephone off the hook and the bed unmade. Trying to remember what happens next. It is more like memory than imagination. The imagination part only happens in bursts of excitement — it happens when it gets ready to happen. Days go by while I work and work and work, and, for some reason, which I have never been able to understand, I am able to put up with this very hard, boring part of writing. Meanwhile I take good care of myself. I sleep at regular hours and eat as intelligently as I can and maybe even clean up the house and buy some flowers for the table. The book is writing itself while these things go on. Then one morning, it was this morning for me for this book, it breaks open, like a flower opening or a storm cloud, and it all makes perfect sense and I know how to write down what I have dreamed or imagined. I know what happens next and what the characters are thinking and how they dance with each other on the page. If it is a short story or a poem two or three of these episodes will do to complete the piece. If it is a novel only Athena knows how long it will take or how many spells of hard, boring, seemingly useless work followed by bursts of illumination must go on before the plot is woven and the book finished.

A piece of writing is the product of a series of explosions in the mind. It is not the first burst of excitement and its aftermath. It is helpful to me to pretend that writing is like building a house. I like to go out and watch real building projects and study the faces of the carpenters and masons as they add board after board and brick after brick. It reminds me of how hard it is to do anything really worth doing.

I’M NOT A bad person. If I see a turtle on the road, I stop and pick it up and return it to the grass. I know the universe is one. I know it’s all one reality. So why does it make me so furious, why do I want to kill and kill and kill when the turtles on the pond kill the baby ducks? They killed seven in April and five more in May and they are at it again.

Edmund Wilson once wrote a great short story on this subject, called “The Man Who Hated Snapping Turtles.” I could have written that story. I wouldn’t have had to invent a character. I could have used myself. One morning I wake up and there are five brand-new beautiful soft fluffy baby ducks following their mother out from behind a grass nest and walking side by side to the water. They enter the water without sound. They glide like angels. The mother looks like my beautiful daughter-in-law Rita. The baby ducks are my grandchildren. A turtle rears its head. Kill, I’m screaming. The neighbors are on their porches. They know what’s going on. We have all been sharing the tragedy of the ducks.

Kill, I’m screaming. Doesn’t anybody have a gun? I grab an empty Coke bottle and run out onto the pier and throw it at the turtle. Success. It scares him off for the moment. Get those babies back on the land, I’m screaming at the large ducks. Don’t you know what’s good for you? Can’t you protect your young?

I can’t stand it. Here we are in the sovereign state of Mississippi and we are helpless to prevent those ducks from getting killed. How am I going to travel and see the world? What’s going to happen when I get to Mexico or India? Get back in the bushes, I’m yelling at the ducks. We’ll drain the pond. We’ll kill all the turtles in the world. What am I supposed to do? I can’t stay in the house and never go out on the porch. I can’t keep the drapes closed so I’ll forget the pond is there. It’s there. The baby ducks are on the pond and the turtles are coming to get them.

STUCK IN THE very heart of summer in the middle of a heat wave and I’m sitting here trying to write this book. Why did I ever start this book? What on earth possessed me to think I could write an historical novel? I remember when I started it. I woke up one beautiful fall morning in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and decided I had missed my calling. I should have been a scholar, I said to myself. I should have kept on learning Greek.

I will write a novel set in ancient Greece, I told myself. Anyone can do anything, and I am going down the hill and go to the library and take out every book ever written about ancient Greece and read them and then I’m going over to Daniel Levine’s office and borrow all his books and then I’ll sign up for Greek classes and I will spend as many years as it takes. I want to be a great and honored writer, a scholar, a serious and noble person.

So I put on my hiking shoes and walked down the mountain and on down to Dickson Street and marched into the library and began. That first month was wonderful. No more the unstructured life of a fiction writer. No more ego. No more taking real life and twisting it into character and scenes and devising plots and opening lines. All I had to do now was sit all day in a little cubby at the university library and read and take notes. I was wearing an old tweed skirt and an oxford cloth shirt and brown brogans and knee socks. My horn-rimmed glasses. At exactly eleven o’clock every morning I would walk over to the student union and eat doughnuts and drink coffee. Who cared if I got fat? I was a scholar now. Lost in the stacks.

Everything was going fine. My time schedule called for me to read and study for five years before I began to write.

I was covering yellow legal pads with knowledge of the past. Plants and herbs, ancient weapons, walled cities, how to mix mortar, how to make cloth, the clothes people wore, their music and sculpture and plays.

Then one morning I stayed home and sat at a sunlit table in a dining room overlooking the mountains and began to read the notes. I was in the dining room. I wasn’t in my crowded messy workroom where I am a writer. I was in a sunlit dining room being a scholar. Suddenly an old story I had made up when I was a child began to appear on the page. A story about a young Greek girl who saves an abandoned infant. Suddenly that old unconscious story, about saving, of course, who else, myself, came rising up and I was writing and writing and writing all day.

I wrote for three or four days. That writing is still the best part of the novel. I may never again write pages as good as those. And here I am, four years later, on the fourth or fifth or sixth or seventh draft of the cursed thing and still writing and still studying and it isn’t finished yet.

This is what a writer’s life is really like. Calling up my editor and my agent nearly every day to get stroked and reassured. Walking around my house blaming the book on everyone I know and scared to death I can’t finish it and scared to death it isn’t any good. “I would never encourage anyone to be a writer,” Eudora Welty once said to me. “It’s too hard. It’s just too hard to do.”

THE INGRATE, part one, or, I have had too much of the rich harvest I myself desired. I am sick of being a writer. Not of writing. Not of the wonderful mystical thing I do all alone in a messy little room I call an office. Not the inspiration, the conception, the writing down of poems and essays and stories. Black ink onto yellow paper, magic. But I am sick of answering questions and signing my name and being loved by strangers. “But I am tired of applepicking now, I have had too much of the great harvest I myself desired.”

Maybe it was that one really nasty irresponsible review. Maybe it is being misunderstood and misinterpreted that drives writers crazy and makes them go off to the hills to brood and pout and stop talking to people. Sixth-grade politics. Fourth-grade emotions. Second-grade sensitivity.

So now I am holed up back in Jackson, Mississippi, with the phone off the hook and the television turned to the wall and I am thinking. I have contracts for three books. I have a wonderful assignment from Southern Magazine to go up to the White River and freeze to death camping out with my boyfriend at Thanksgiving. I have three children and three grandchildren, all in perfect health. My new book is selling well despite the New York Times. I work for the best radio program in the United States of America. I live in the greatest silliest wildest country that ever raised a flag on a flagpole. And I’ll be all right as soon as I get some rest.

Yesterday I was talking on the phone to a writer, and she asked, “Are you writing anything?” And I said, “Of course not.” And she said, “Well, that’s publication.”

IT IS IMPOSSIBLE to be stupid while listening to Bach. There is something about the art of fugue that soothes the brain. I used to make a joke about this and tell my friends they could stop suffering love if they would stop listening to love songs and listen to Bach instead.

Recently, in the middle of a rainy Sunday afternoon while I was lounging around on the sofa in the middle of a pile of books, worrying about my children and getting my mind in a tangle with this or that imagined catastrophe, I came upon a chapter in a book of Lewis Thomas’s essays in which he explores the proposition that he could go to the scientists of the world and ask them for the answers to three questions.

The first would concern the strange mind-reading abilities of honeybees.

The second question would be about music. “Surely music,” Doctor Thomas says, “along with ordinary language, is as profound a problem for human biology as can be thought of, and I would like to see something done about it. What music is, why it is indispensable for human existence, what music really means. Hard questions like that.”

“Why is the art of fugue so important and what does this single piece of music do to the human mind?”

As soon as I read that I put down the book, went to the closet where I store my records, found a Bach recording, put it on the stereo, and by the third musical phrase the tangles in my mind were unwound and I knew what to do next. The piece I was listening to was Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in C Major, perhaps the most beautiful piece of music in the world.

I never did find out what the third question would be.

I WOKE THIS MORNING dreaming of the woods. An opening in a line of trees seemed to lead deeper and deeper into the woods, perhaps to a pasture, perhaps to a river. Tall pine and oak and sycamore trees arching above me and a small road of pine straw and fallen leaves to walk upon, a golden mattress of a road. It was very still, the very heart of the woods, and I was alone there and perfectly quiet and perfectly happy. Some weeks ago Southern Magazine asked me where I would like to go in the South, what I would like to investigate and learn about and praise. “The rivers,” I answered without thinking, without having to pause to think. Wherever there are rivers and trees I am happy there. I have lived too long to trust the places man has spoiled and changed and bought and sold. They have failed me every one. I cannot even remember the names of the resorts I have gone to with my rich husbands, the sadness and drunkenness and disorder of those places. But the woods. I remember every river I have ever set out upon, every pond and lake and swimming hole, every forbidden borrow pit, every tree I ever climbed or leaned into or loved. “I will go to a river,” I told the editor of the magazine. “It won’t cost much to send me where I’m going. If only I can find my tent.”

“Which river?” he asked.

“Somewhere in Arkansas,” I answered. “In the Ozarks. Let me call my guide and get out maps and I’ll get back to you.”

Of all the people I have ever gone camping and river-hunting with the one who suits me best is a young man from Fayetteville, Arkansas, named Mack Harness. I call him the Trout Fisherman. He calls me the Famous Writer. We get along in the woods. I trust him not to let me get killed and he trusts me to get sullen when he smokes. It’s a nice arrangement and we have been camping out and hunting rivers and admiring trees and rocks and waterfalls together for about seven years. So I called up the Trout Fisherman and asked him to come down to Jackson and help me. He flew down and we spent a weekend looking at maps and eating roast beef sandwiches and Oreo cookies and vanilla ice cream. About ten o’clock on Sunday morning, while listening to The Well-Tempered Clavier, we came up with something we liked.

“Let’s go up here,” I said, pointing a finger to a place on a map southeast of Fayetteville and somewhat west of Memphis. “Let’s go find the source of the White River.”

“Looking for the White,” he said. “That’s great.”

“Where is this?” I asked. “Here, take the magnifying glass. Goddamnit, we’ve got to get some better maps. We need some geological survey maps. Here is where it should be. Right here.”

“That’s up by Venus Mountain. We can find that.”

“We’ve got to go to wherever it rises. Even if it ends up being in Missouri.”

“When are we going?”

“The week before Thanksgiving. I can’t get away till then.”

“It’s going to be cold.”

“I know. Well, you’re tough.”

“That I am,” he said, and walked out on the balcony to smoke a cigarette.

November 16, 1986.

I can’t wait. The woods are there and the Ozark Mountains and the rivers so cold and clear and moving so fast. Calm down, I tell myself. They have been there a long time. They’ll be there when you get there. And you can make a fire and sleep in your tent. If I can find my tent. When last seen it was in my son’s apartment in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It had better be there when I get there with no holes in it if he ever wants to borrow it again. What else do we need for a river trip? Some health food. Fritos and Nacho Cheese Flavored Doritos, Vienna sausage and rat cheese and soda crackers and chocolate chip cookies and chewing gum (in case anybody decides to stop smoking).

November 16.

The Trout Fisherman will fly down to Jackson on November 20 and on the twenty-first we will drive up through the Mississippi Delta, through the deltas of the Yazoo, then the Sunflower, then the Mississippi (where I was born) and across the Mississippi to the Arkansas Delta (where the Trout Fisherman was born).

We will cross the river at Vicksburg and ride up the Arkansas side to Lake Village, the most beautiful town in the world, and on up to Pine Bluff, which has been ruined by paper mills and an arsenal for binary nerve gas, then on to Little Rock where we will tip our hat to the editor of Southern Magazine who put us up to this and is paying for the Oreos and Fritos and Nacho Cheese Flavored Doritos and Vienna sausage and soda crackers and gasoline and camera film and, God forbid, the Camel cigarettes.

November 21.

Bad news and a change of plans. The Trout Fisherman has had a death in his family and now will meet me in Fayetteville the Monday before Thanksgiving. So much for our drive up through the deltas, but we’ve done that before and will do it again in a happier season.

For now I will fly up alone on Monday and we’ll find our tent and head out on Wednesday morning. The tent will only be an icon now. The Ark of the Tent. The Tent of All Tents will spend the week rolled up in the back of the Isuzu and we will go find the source of the river and return to spend the night in the Designated Driver’s geodesic dome near Goshen, Arkansas, which looks down four hundred feet onto a beautiful S-curve of the river and the fields it feeds and guards. We will sleep near water in this house the Trout Fisherman helped the Designated Driver build. “We are getting soft,” I told the Trout Fisherman. “I know,” he answered. “Well, that’s how it falls for now.”

Since we were ruined anyway we decided to get really decadent and spent the evening seeing a double feature. We saw Peggy Sue Got Married. Took a Coke break and went back in for Star Trek IV.

November 24. Jackson, Mississippi, Airport, 9:00 A.M. waiting.

Leaving Jackson in a hard gray rain. Cold, straight rain with flash flood warnings. I hate to fly in weather like this. Also, I hate to leave my work as I was writing well, working on The Anna Papers.

But a writer has to make a living. Also, a writer has to have some fun or the work gets cold. This may be too much fun. Since September I’ve been on twenty-eight airplanes. Well, two more takeoffs and landings and I’ll be in Fayetteville, pick up a four-wheel-drive Isuzu, meet the Trout Fisherman and the Designated Driver, and I’ll be on my way.

10:53. Takeoff.

Always a holy moment. We are flying a Northwest Airlines Saab Fairchild 253, made in Sweden, land of the gorgeous Socialists.

Notes on plane: Good title for book, Principles of Flight. The Pearl River below me shrouded in mist, wreathed in clouds. So beautiful. Tall pines and orange-leaved oaks along its banks, cold gray water. Eudora’s river. She made it famous in the lovely short story “The Wide Net.” Also, her character King McClain left his hat on the banks of the Big Black and some say he died and others say he ran away. Rivers. So wonderful to know and love the rivers of your state.

Flying over Mississippi at ten thousand feet in bad bumpy weather I think about my ancestors who came here on boats down the Monongahela and the Allegheny to the Ohio and on down the Mississippi to Natchez and Mayersville. What would they think if they could see me now, daring to complain about anything?

We are approaching the Sunflower River. I can see it below me through the rain. I am wearing a soccer shirt, khaki skirt, boots, and an old raincoat one of my teenagers outgrew and left behind.

Above Greenwood things got so beautiful I could hardly bear it. Small scattered featherlike clouds above a winding chocolate-brown river. The multicolored trees of Mississippi, cold and shrouded with mist, water oak, sycamore, maple, pine, dogwood, and persimmon.

We landed in Memphis in a downpour and let some folks off and took some more on and took off again for Fayetteville. I am getting excited now. Going home, I have promised John Dacus at Hayes and Sanders Bookstore to be there at four for a book signing. It looks like I am going to make it after all.

5:00: The Trout Fisherman shows up at the bookstore wearing a coat and tie. “I’m ready,” he says. “Sign my book.” “So am I,” I answer, and write my initials on his wrist. [Some people never grow up.]

November 25.

Fayetteville. Tuesday: Cold wet misty weather. One more day and we will leave to find the river. Perhaps the weather will clear by then and we will have a good day for the expedition. The Trout Fisherman and I are camped at the Mountain Inn where the big news is that there has been an accident at the Fayetteville water plant and no one can drink the water. Strange and prophetic that even in this remote mountain town the water is not safe. Too many people in one place. Any Indian could tell you that. The Trout Fisherman is part Cherokee, he becomes diminished when he stays too long in cities, as I do.

When we checked into the hotel the desk clerk handed us each a gallon of bottled water and we carried them to our rooms.

Later: It is raining cats and dogs. The Trout Fisherman left in a deluge to retrieve the four-wheel-drive Isuzu from the repair shop. He returned two and a half hours later with bad news. He had stopped off to shoot pool at Roger’s Pool Hall. It was dark when he came out and the lights wouldn’t work on the Isuzu. We decided to try to get them fixed in the morning even though it might give us a later start. Perhaps I will get to unroll the green tent after all. I went to sleep dreaming of what we would find. A spring trickling out of the ground, disturbing the leaves somewhere halfway up a hill. Would there be a marker? There was none noted on the map. People in Arkansas are good about leaving things alone. Perhaps there would be nothing there but water. I went to sleep with water beating on the panes outside the windows of my room, falling down gullies and ravines in my dreams.

November 27: Making Our Own Fun, Or, Why Are We Always So Crazy?

5:30: Woke up. Argued about the lights on the Isuzu.

5:45: Trout Fisherman goes out to work on lights on the Isuzu. No luck.

6:10: Called Trout Fisherman’s brother. Tried to borrow a truck. No luck. He was driving it to Shreveport.

6:30: Packed Isuzu. Ate breakfast (bacon, eggs, toast, pancakes, hash browns, coffee, syrup). Got in a remarkably good creative mood.

7:00: Drove Isuzu to Jim Ray Pontiac where a masterful service manager understood our problem, mobilized a team of mechanics, and had us on our way with a new light switch in fifteen minutes. I love Fayetteville. Where else will people take writing a story that seriously? Where else will people try to save you money while they sell you something? Salespeople in Fayetteville were always doing that for me when I lived there, pointing out bargains, telling me to wait for the sale, helping me curb my extravagant Delta ways.

November 27.

We are on our way. So much water. Rain and mist and clouds, a cold wet misty freezing thoroughly gray day. Perfect morning to go searching for a place where four rivers rise.

We drive out past Goshen to pick up the Designated Driver who lives in a dome overlooking the White River just below Beaver Lake. The Designated Driver is Dave Tucker, an old friend who makes his living as a commercial artist and illustrator. He is also, not incidentally, one of the best jazz and fusion drummers in the Ozarks and played rock and roll with the Trout Fisherman’s band in their high school days. It’s a good crew. It’s going to be a good trip. We can feel it in our bones.

We inspect the river from Dave’s balcony. Then we go down the long gravel road and out onto Highway 45, backtrack past Goshen and find Highway 16 to Elkins. It is still misty, gray from horizon to horizon. The only leaves left are on the oaks. We can see the lay of the land, the architecture of the trees, uncovered fences, cows in pastures, red and green and brown fields, barns and silos. We pass the Victory Free Will Baptist Church, Guernseys and Herefords, a field of Appaloosas, their black spots showing on their wet hides.

Near here the West Fork of the White meets the middle fork at the bottom of Lake Sequoyah. “The first dam on the lake is at Sequoyah,” the Trout Fisherman says. Later we will learn that isn’t so.

We go from 71 to 265 to 68 east, past Sonora, and onto Highway 16 toward Elkins. Between Tuttle and Elkins we get our first glimpse of the river before the dams.

Beautiful country. We drive past apple and peach orchards and vineyards with their black configurations set like Chinese characters against the tilled soil.

Near here, in Madison County, up around Red Star, a hundred little gaps and rises and valleys are the last hideouts of the hippies, the ones that went back to the land to stay.

Everything in the Ozarks is very simple still. Even pollution doesn’t seem to have made great inroads into the beauty. Still, I remember when I first moved here, in 1979, and the scientist Anderson Nettleship, now deceased, would proclaim to me about acid rain falling on our forests from smokestacks thousands of miles away. I felt helpless in the face of that but Dr. Nettleship did not. He protested it loudly all his life, in person and in many letters to the Powers That Be.

Another thing he used to lecture me about was the sheer idiocy of romantic love. “Childbirth, of course,” he would begin, “is the true manifestation of the creative urge. But that is another matter.” The Trout Fisherman and I knew Dr. Nettleship and loved to talk with him. If he had still been manifest he would have made a wonderful companion on this trip.

9:50: At Tuttle we get our first view of the river above the dams. Here the river is at its widest, sixty to a hundred feet. This is the river before it starts being fucked up. Wide green flood plains, bottomland as it’s called in the hills, the watershed, what the river drains. Near Brashears we pass a house with white ceramic chickens and a red wagon beside a well. Perfect and right.

Near Combs there are white cattle against green and red fields. In the background a stand of white birch trees against a gray sky. A patch of sunlight beginning to show in the east.