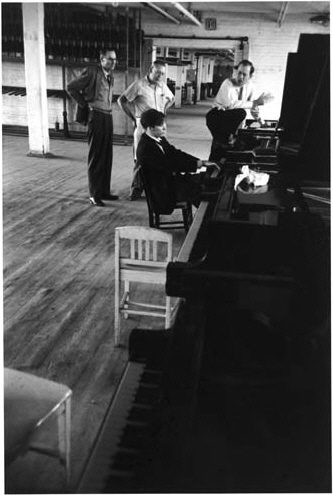

Trying out pianos in the Steinway

Basement in 1958. Gould with Fritz

Steinway (with leg up) and two other

Steinway & Sons employees. Photograph

by Don Hunstein, courtesy of Sony

BMG Music Entertainment.

EDQUIST MAY HAVE BEEN mostly blind, but there was no mistaking the tangled wreckage that CD 318 had become. The piano’s previous dents and battle scars were insignificant compared to the condition it was in now. Merely dinged before, the lid was now completely twisted out of alignment and split apart at the bass end, its hinges horribly bent.

Edquist carefully removed the lid and peered inside, feeling with his fingertips. Then he crawled beneath the piano and, by touching the underside of the soundboard, could tell that it was split at the treble end. This meant that the thirteen-hundred-pound piano hadn’t just slipped an inch or two. To receive such a gaping crack, it must have suffered a huge impact. It must, Edquist concluded, have plummeted at least several feet. Edquist also detected several cracks in the two-inch-thick keybed. It seemed that on impact, the action had shot forward several inches, taking with it the key blocks as well as a number of heavy screws and the dowels that held them in place. In its path, the runaway action had mowed down the key slip—the long, narrow, vertical strip of wood pinned to the front of the keybed—which was now pushed out and twisted.

But what shocked Edquist the most during his inspection was a large crack in the piano’s iron plate, a 350-pound mass that is strong enough to carry twenty tons of string tension. When a piece of metal holding that much tension breaks, it would create an explosive sound that would rival a cannon firing. It was impossible, Edquist knew, that anyone present could fail to hear the combined noise of the piano falling and the plate exploding, so he presumed that the only people present at the loading dock were the crew of movers—three, maybe four men from Maislin or Robertson’s, the local companies Eaton’s hired for piano transport. Clearly they were alone at the dock and, rather than call the accident to anyone’s attention, they had simply hoisted the piano, still in its crate, back to the spot from which it had fallen off the dock, taken it into the freight elevator, uncrated it, rolled it into the auditorium, set it up at the foot of the stage, and gotten the hell out of there. And to Edquist, that was the oddest part: The piano had simply been left as if nothing had happened, propped in place like an inconvenient corpse. The movers must have hoped no one would notice.

This wasn’t the first time Edquist had seen a piano after a disaster. He had been asked to work on instruments that had been left outdoors in freezing temperatures, which causes the metal plate to grow brittle and, on rare occasions, even crack. But he had never seen anything quite like this. The extent of the damage to CD 318 was so extraordinary, Edquist recalled feeling that it was almost as if someone had committed intentional violence on it. Most worrisome of all, though, was the prospect of breaking the news to Gould. Edquist’s first thought was like a child’s reflexive relief at not being at fault. His next thought was that he didn’t want to have to be the one to tell Gould what had happened.

As the evening wore on, others began to filter in for the night’s recording session. Roberts began to unload the equipment, but Edquist told him not to bother because there wasn’t going to be any recording that night. Andrew Kazdin and Lorne Tulk showed up shortly thereafter. Dolefully, the four men clustered around the damaged instrument. As they examined it more closely, they discovered that the cast-iron plate was cracked in not one but four places. It was then that someone raised the question: What to do? Should someone go to Gould’s apartment, ring the bell, and break the news as if CD 318 were a fallen soldier? Should they just wait until he arrived at the auditorium? They agreed that Gould had to see the piano for himself, but that he ought to be forewarned with a telephone call. After some discussion it was decided that Edquist, who knew the piano and its passionate owner best, should be the one to make the call. An hour later, Gould arrived at the auditorium in a state of unexpected calm. He walked up to the piano, took a brief look at the keyboard, and, without so much as touching a key, said, “Can’t play on that.”

He told everyone they could leave; there was no work to do. Feeling an extra measure of responsibility, Edquist stayed behind with the pianist and his broken instrument. Once he was alone with Edquist, Gould grew more agitated. Together they went over what might have happened. “He grilled me like a lawyer,” Edquist recalled. After a few minutes it was clear that there were too many questions, and neither man had answers.

The first thing Edquist did the next morning was go to the Eaton’s loading dock to examine the packing crate the piano had been shipped in. He found a deep gouge on the left-hand side near the top, and discovered that the wood block inside the case, which was used as a brace, had been torn loose by the force of the crash. Edquist then went upstairs to see Muriel Mussen, who coordinated the comings and goings of Eaton’s concert grands. It came as no surprise to Edquist when she told him she knew nothing of the accident. Yes, she said, it was Robertson’s that had delivered the piano, but no, they had reported nothing to her. When Edquist described to Mussen the extent of the damage, she expressed shock and sympathy. She knew how Gould had plucked the old, rejected, homely CD 318, Cinderella-like, from backstage in the auditorium, how he had come to love it, and how he and Edquist had spent years modifying it to perfection. She could only imagine the anguish Gould must have been feeling.

Yet Gould, for his part, maintained an almost eerie calm. If he was devastated, he did not show it. Almost immediately he seemed resigned to the irreparable state of the piano. Soon after the accident, in a letter to David Rubin at Steinway, he was referring to the piano as if speaking of a beloved family member whose resuscitation no one had bothered to attempt.

The letter to Rubin laid out the damage in clinical detail:

The piano was apparently dropped with great force and the point of impact would appear to be the front right (treble) corner.

The plate is fractured in four critical places.

The lid is split at the bass and there is also considerable damage to it toward the treble end as well.

The sounding board is split at the treble end.

Key slip pins are bent out of line and the force of the impact was great enough to bend No. 10 type screws as well.

The force was also great enough to put the key frame and action completely out of alignment, i.e., forward at the treble end.

Gould wrote, “I am sure that these details will be substantially borne out by your technical people when they have a chance to assess the damage.”

Yet for all his attempts at pragmatism, inwardly Gould was bereft. He was determined to find out who was responsible for destroying the piano, and he decided to sleuth the episode out for himself.

Robertson’s, the moving firm, had a good reputation. Like Muriel Mussen before him, Gould could find no accident report in relation to any portion of the piano’s journey back from Cleveland. It seemed to be the piano-moving equivalent of a hit and run. “While it was possible that whoever dropped the piano failed to appreciate the degree of internal damage which such a fall would cause,” he wrote to Rubin, “I think the external damage alone to the case would be more than sufficient to have warranted a report of some kind.”

He consulted with Mussen to gather details about the time and means of the piano’s transport. According to her records, CD 318 had been crated on September 17, 1971, picked up by Maislin Transport, and trucked to Cleveland. More than a month later, when the piano was en route back to Toronto, Robertson’s picked it up from “the Dump,” the nickname for the customs shed on the outskirts of the city.

It was the return trip that most interested Gould. He pieced together a timeline, and discovered that the piano had undergone a trip so slow, it might have arrived in Toronto from the Canadian border more quickly had someone rolled it down the street. According to Mussen’s records, the piano reached the border on October 13, three weeks after leaving Cleveland, via a trucking company called Intercity Transport. It arrived at the Dump the following day. That made some sense. What didn’t, at least to Gould, was that it took three days for CD 318 to clear customs—where it was presumably uncrated and inspected—and then another two days for Robertson’s to take it the few miles from the customs shed to the delivery ramp at Eaton’s. It was not installed in the auditorium until October 26, nearly a week after arriving at Eaton’s.

Gould found parts of this chronicle intriguing—and suspicious. In a letter to Steinway a few weeks after the accident he wrote: “The most obvious query would relate to the fact that it took them six days (admittedly counting a weekend) to move the piano from the ground floor to the seventh-floor auditorium; I also find it odd that it would require two days after customs clearance to go from the suburbs to the downtown store. I would ask that you handle these latter bits of information, or more accurately my paranoid suspicions in regard to them, with your customary discretion, but I’m sure you will agree that both questions could stand some elucidation.”

It could be that Gould had just never paid much attention to the logistics of moving pianos from one city to another. And why should he have? His interest in piano moving heretofore began and ended with seeing the instrument properly situated on a stage or in the studio. Still, when he went over the timeline with Muriel Mussen, she agreed that CD 318’s journey home from Cleveland had been tortuously slow.

Piano moving is an inherently tricky business. In cities filled with multistory apartment buildings with impossibly small elevators or narrow stairwells, pianos are often hoisted in the air, attached by reinforced steel cables, and moved by crane through a living room window. Nine-foot grand pianos have been moved in hotel elevators not inside the elevator car but on top of it, tied to the cable. The task of moving a piano, especially one as large, heavy, and oddly shaped as a concert grand, involves such challenging geometry that it has inspired its own mathematical puzzle, known as the Piano Mover’s Problem. Robotics researchers in particular were intrigued by what they called a “motionplanning” problem that arises regularly in robotics, where the goal is to find an algorithm for moving a solid polyhedron (piano) from a given starting point to a given end point without colliding with a region bounded by impenetrable and immovable solid objects (walls, doorways, stairwells). In real life the apprenticeship of a piano mover is lengthy, and the level of confidence in an apprentice needs to be very high before he is allowed to move a piano, especially a grand, unsupervised. The crew from Robertson’s was acknowledged to be among the best, and several of the movers at the company had moved nothing but pianos for years. The Robertson’s crew had transported thousands of pianos under circumstances far more difficult than these.

Trying to make sense of what had happened, Gould focused on forensics. From the way the piano was damaged, it was obvious that it had tumbled headfirst. The specific loading dock that the piano arrived at was about five feet high, which would account for the force of the impact. It was also clear from the damage to the crate that the piano had been dropped before it was taken out of the crate. The accident could have happened as it was coming off the truck if the length of the crate exceeded the length of the truck lift. If the skid was longer than the lift gate, at some point it would protrude over the edge. With formidable weight come problems of balance and inertia. Moving a grand piano requires not just strength but constant communication. Good piano movers are always talking to each other in short, gruff bursts: “I’m there,” and “One, two, go!” and “You take the top side,” and “To you!” and “Watch the balance.” Toronto’s best movers—the crews sent out by Maislin and Robertson’s—were so experienced, so accustomed to the demands of these tasks, that they became second nature. But inexperienced movers can easily forget that two thirds of a grand piano’s weight is concentrated at the front of the instrument, producing a center of gravity so biased toward one end that perfect balance is essential—so much so that a moment’s inattention can result in disaster.

Gould believed it was unlikely that professional piano movers had dropped CD 318. It was far more likely, he concluded, that the culprits had instead been Eaton’s employees who worked with shipments leaving and arriving at the loading dock but who had no particular expertise in moving concert grands on and off the large vans. Typically, the movers delivered a piano as far as the loading dock, then left it for the Eaton’s crew to take it to its final destination, which for CD 318 was the auditorium. And in the end, this was Robertson’s claim: The moving company delivered the piano to the loading dock and after that, somehow, it fell, or was dropped or knocked off the edge.

Not long afterward, a story circulated that someone who was inside Eaton’s at the time saw the stage manager rushing out of his office and, when asked what was wrong, heard him reply, “We just dropped a piano!” Later this individual denied having uttered those words. “It was a third-party story at best,” Ray Roberts said many years later. “You’re not going to go to court with that.”

Eventually, no doubt frustrated by the dead ends he kept encountering, Gould dropped his investigation. Over the years, when telling interviewers about the accident, he pointed no fingers, saying only that it happened at a loading dock, and that for him it was a tragic incident. He was right to let it go. Even if he had managed to figure out who was responsible, there would have been no way to prove it. And in the end, did it really matter? The damage had been done. The question for Gould became, Where to go from here?