The democratic government of France is said to have invented a new system of foreign politics, under the names of proselytism and fraternization. My present letter … will show that an internal interference with foreign states, and the annexation of dominion to dominion for purposes of aggrandizement are among the most inveterate and predominant principles of long established governments. These principles, therefore, only appear novel and odious in France because novel and despised persons there openly adopted them.

—Benjamin Vaughan, 1793

It is with an armed doctrine that we are at war. It has, by its essence, a faction of opinion, and of interest, and of enthusiasm, in every country. To us it is a Colossus that bestrides our Channel.

—Edmund Burke, 1796

IN DECEMBER 1848, LOUIS-NAPOLEON, nephew of his infamous namesake, was elected President of France’s infant Second Republic by a wide margin, a few months after France’s third modern revolution had overturned the constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe. Louis-Napoleon was elected by a coalition of conservatives and moderates alarmed at the radicalism of the Republic’s provisional government. Judging from his writings prior to his election, Louis-Napoleon’s primary goal was to restore France to pre-eminence in Europe without resorting to war.1 Upon assuming office, the new President quickly sought a congress of the great powers to renegotiate the Vienna settlement of 1814-15, which had left France weak. Among his goals for this congress, to be held in Brussels, was a reduction of Austrian influence over the Italian peninsula. To Louis-Napoleon’s surprise, the British government refused his invitation to join him in proposing the conference, fearing (probably correctly) that that congress also would seek to overturn the recent revolutions that had sprung up all over the continent.2 Thus far those revolutions had weakened Britain’s rivals Austria and Russia

So the Brussels Conference never occurred. Instead, Louis-Napoleon reluctantly joined a conference of Catholic powers called to address one particular revolution, that in the Papal States. Pope Pius IX, who had begun his papacy in 1846 as a liberal reformer, found that his reforms did not appease radicals in Rome and elsewhere. As the 1848 revolutions cascaded across Europe, republicans in the Papal States rebelled, demanded a lay government, and removed the Pope’s guard. Imprisoned in the Vatican, Pius fled Rome in November 1848 rather than accept a republic. When Giuseppe Mazzini and other revolutionary leaders declared a Roman Republic a few months later, Pius appealed to the governments of Spain, France, Austria, and Naples to restore his temporal authority.3 It is clear from the negotiations at the Catholic conference that two outcomes were unacceptable to the French President: continuation of the new Roman Republic, and an Austrian restoration of the Pope. Louis-Napoleon wanted Italians to restore Pius by themselves, but when it became clear at the conference that the Italians required outside help, the French Assembly in Paris quickly voted to fund a French expedition to pre-empt Austria and restore Pius.4 Louis-Napoleon quickly sent to Rome a force of 9,000. Giuseppe Garibaldi’s republican forces fought back fiercely, but French reinforcements decided the contest easily. Pius ascended his throne again as an absolute monarch.

Why both Louis-Napoleon and mainstream French opinion found Austrian restoration of the Pope unacceptable is no mystery. Virtually all French elites wanted to roll back Austria’s control of Italy. But why then should France restore the Pope rather than provide diplomatic and material support to Mazzini, Garibaldi, and the other Italian republicans? The left wing in the French Assembly pushed for this policy and protested vehemently when France, now a republic again after all, betrayed a fledgling sister republic in favor of a symbol of the ancien régime.5 That Pius himself preferred to be reinstated by Austria, a conservative Catholic power, suggests that France would have had a more loyal client in the Roman republicans. (And in fact, upon his restoration Pius did lean toward Austria, which he correctly believed more strongly supported the status quo in Italy.)6

Louis-Napoleon re-imposed the Pope’s absolute monarchy in Rome out of a concern for his own domestic power. He was facing a domestic and transnational threat from the revolutionary left. As his 1839 book Idées napoléoniennes showed, Louis-Napoleon was, like his uncle, a man of the Enlightenment, but also a man who believed that authoritarianism was required to force Enlightenment principles of rationality and freedom upon society.7 In 1848, as in 1793, the Enlightenment had seemed to spin out of control in France, particularly when a worker’s rebellion in June raised the specter of communism and was met by brutal military suppression. Louis-Napoleon had been elected President because he promised stability and an end to destructive factionalism. The factions included the absolutists or legitimists, who sought a restoration of the Bourbons under the principle of divine right; the Orleanists, who had supported the constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe; the Bonapartists; the moderate republicans; and the radical republicans or “Mountain.” Louis-Napoleon sat atop a coalition of absolutists, Bonapartists, and moderate republicans—groups that had in common only enmity toward the radical left.

Louis-Napoleon never considered supporting the republicans in Rome because they were part of this same transnational radical enemy. Although himself a former revolutionary who would not have come to power in France without the Revolution of 1848, he obviously was now interested in restoring France’s politics to the status quo ante. Soon after his election he suppressed the radical Left by suspending constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech, assembly, and the press. He approved of bills to restore Church control over education and to add a three-year residency requirement for voters, shrinking the rolls from 9.6 million to 6.8 million.8 It was clear to friend and foe alike in 1848-49 that the radicalism still alive in France was linked to revolution everywhere. Radicalism was a transnational movement and revolutions enjoyed demonstration effects. Thus, a victory for the radicals in Rome was a victory for the radicals in France

At the same time, the factions atop which Louis-Napoleon sat uneasily had various reasons to favor papal restoration. For the absolutists, mostly devout Catholics, Pius’s overthrow was a real threat to the Church’s own power in France. The moderate republicans had no particular affinity for Pius, but they shared his transnational enemy, radicalism. Louis-Napoleon thought to satisfy them by arguing that if France restored Pius he would govern as a constitutional monarch; if Austria, he would become an absolutist.9

Louis-Napoleon’s forcible promotion of absolute monarchy makes little sense apart from the high degree of ideological polarization across the societies of Europe in 1848-49. Had populations across the Continent not identified so intensely either for or against revolution, Italian conservatives would not have been so pro-Austrian and there would not have been so many French radicals to intimidate Louis-Napoleon and his supporters.

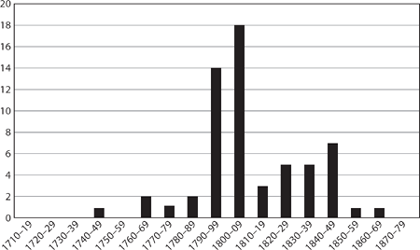

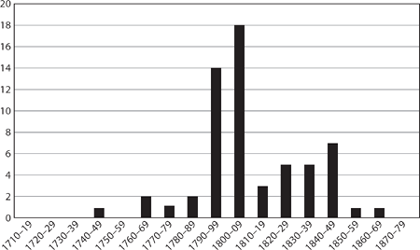

Figure 5.1 Forcible regime promotions, 1710–1879

Between the early eighteenth century and the 1780s, states continued to vie for position, threaten and fight wars, trade, and align and de-align in various patterns. Within and across societies, ideas about the best public order competed for allegiance. Yet, those decades were not roiled by transnational clash of ideas comparable to that which had thrashed Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (chapter 4). No central set of ideas or common political language animated and united the discontented across states; no network of revolutionaries spanned Europe; no ideology of reaction gave governments a strong common interest. On the Continent of Europe, most rulers were bent on centralizing power in the manner of Louis XIV of France. Monarchs centralized power by subduing and co-opting nobles and continuing their traditional roles as alleged defenders of the peasantry against the nobility. With no sustained transnational contest over the right regime, monarchs were freer to act in accordance with state-centric Realpolitik. The eighteenth century, prior to the 1780s, was a period of classical power balancing. Indeed, in 1770, David Hume published his essay on the balance of power as a self-regulating or natural law of international relations. Wars were fought for territory, dynastic succession, and commerce, and only seldom for principles of government.10

From the 1790s through roughly 1850, however, the incidence of foreign imposition of domestic regimes rose sharply in Europe and even spilled over into the Americas (see Figure 5.1).

The institutions being promoted and opposed had to do not with religion but with monarchical authority or sovereignty. As in the church-state struggle of the preceding centuries, the permutations were many, but in general three types of domestic regime were promoted: absolute monarchy, in which the crown was formally unconstrained by law; constitutional monarchy, in which the crown was accountable to law as interpreted by some independent body (typically comprising the nobility); and republicanism, in which there was no monarch.

Struggles over the locus of sovereignty—crown, nobility, and people—were perpetuated by networks of elites across societies. TINs during this period were seldom as coherent or centralized as were Catholicism or Calvinism in the earlier period, and they had conflicts of interest that often derived from national rivalries. Nonetheless, each showed a similar tendency to see itself, and to be seen, as continuous across time and space. Each also coalesced and swelled during polarizing events, particularly a regime crisis somewhere in the region or a great-power war. Transnational ideological polarization would present rulers with threats and opportunities. Rulers would often respond by using force to try to promote their own regime or at least block a rival regime.

The American Revolution of 1776-83 detonated the contest, and in the 1790s, the First French Republic became republicanism’s great-power exemplar and carrier; after Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup d’état in 1799, republicanism lacked a clear champion except for the distant and isolated United States. The paladin of constitutional monarchy throughout the period was Great Britain. Absolutism was exemplified and propelled by the three eastern monarchies of Austria, Prussia, and Russia. The 1780-1850 period was complicated by the sixteen-year rule of Napoleon (1799-1814), whose regime was a hybrid of absolutism and republicanism that itself split and polarized actors in other countries.

The threefold ideological struggle emerged in the 1770s and 1780s as a result of the manifest failures of absolute monarchy to satisfy the promises it made to nobles and commoners. At first the resistance came from constitutional monarchists; then a new and potent republicanism took the stage. The grand struggle endured as long as states that exemplified each model continued to be credible. The contest finally faded in the 1870s with new bargains across Europe between absolutists, constitutionalists, and some republicans, in the form of reforming conservative regimes. It was the radicalism of the 1848 wave of revolutions that drove elites to this new bargain which ended forcible regime promotion for a number of decades.

In a deep sense, later illumined by Alexis de Tocqueville, the old regime whose legitimacy crisis ushered in the long wave of ideological promotion was the feudal system in which three estates—monarchy, clergy, and aristocracy—shared power.11 But that old regime was itself a battleground for various struggles—not only that between clergy and the secular princes (chapter 4), but one between monarchs and nobles. For most of the eighteenth century on the Continent of Europe, monarchs were winning. The predominant regime type had become absolute monarchy, a set of institutions predicated on the total authority of the monarch over society owing to his legitimate (lawful) claim to the throne. When absolute monarchy began to confront serious anomalies in the 1760s and 1770s, it entered a sustained crisis throughout Europe (and the Americas) in which it contended with two competitors, constitutional monarchy and republicanism.

Absolute monarchs were unaccountable to any noble assemblies or constitutions or laws; they answered only to God. The divine accountability of absolute monarchy may obscure the regime’s debt to the Enlightenment, the philosophical, scientific, and cultural movement that developed from Renaissance humanism. The Enlightenment is a term used to cover a turn in philosophy and science away from teleology to mechanism—away from the ancient and medieval emphasis on metaphysics, or learning the nature of things, and toward the modern emphasis on purposeless cause and effect. As Francis Bacon put it, natural science must abandon the “vain pursuit” of metaphysics and turn to “history mechanical,” which “is of all others the most radical and fundamental towards natural philosophy; such natural philosophy shall not vanish in the fume of subtle, sublime, or delectable speculation, but such as shall be operative to the endowment and benefit of man’s life.”12 The shift from Aristotelian to Newtonian physics is exemplary: Isaac Newton showed that an apple fell to earth not because it was in the apple’s nature to do so, but because of the mechanical force of gravity. Newton and other new scientists relied on direct observation of matter in motion rather than on traditional authority; hence the Enlightenment stressed the overthrowing of tradition, particularly as borne by the Church.

The Enlightenment’s sociopolitical project followed: if institutions were liberated from the dead hand of tradition, mankind would benefit from the true understanding of how the world works. For most Enlightenment thinkers that understanding would be mechanistic: in the social as well as the physical world, efficient causes operated and talk of final causes or the soul was mere speculation.13 The point of knowledge was practical, “the relief of man’s estate,” as Bacon had put it in 1605. And man’s estate would be relieved if men, in Immanuel Kant’s words, would “Sapere aude!” or “Dare to know!”14

To many leading minds of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Enlightenment implied not democracy but the centralization of power under the rational administration of an enlightened monarch. For Thomas Hobbes, the use of right (secular) reason yielded a theory of absolutism, in which the sovereign has few meaningful limits to his power.15 It is true that constitutionalists and republicans could also appeal to the Enlightenment. For John Locke, right reason produced a more limited sovereign in which the subjects may decide when the monarch has violated the social contract and overthrow him.16 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, writing nearly a century after Locke, argued in favor of popular sovereignty. But historians ever since have been unsure whether to count Rousseau as an Enlightenment thinker at all.17 And in any case, for most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Enlightenment emphasis on the new mechanistic science over against that taught by the Church sat most comfortably with monarchs desiring to seize power from Church and nobility.

The privileges of the nobility rested upon tradition, not abstract reason. Kings took it upon themselves to apply scientific principles to society by rationalizing public administration and making nobles and bishops into instruments of monarchical power. As most Europeans remained devout Christians, monarchical aggrandizement was also supported with the doctrine of the divine right of kings, which eventually was to conflict with the Enlightenment. But even divine-right theory came to be grounded not in the traditional authority of the Church, but in scripture as interpreted by the individual. Bishop Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet’s robust defense of Louis XIV’s absolute power, Politics Drawn from the Very Words of Holy Scripture (1709), invited the reader to consider the biblical data for himself, as a Protestant would, rather than to rely on clergy and bishops.18 Religious skeptics also embraced absolutism. Voltaire, a leading anti-cleric and author of The Age of Louis XIV (1752), regarded Louis (r. 1643-1715) as being “responsible for the rebirth of civilization” after the “gothic and barbarous” Middle Ages.19

Louis, France’s “Sun King,” was the exemplar of enlightened absolutism. Louis owed his subjects justice tempered with mercy, but it was God’s, not theirs, to judge whether he fulfilled his obligations. In concrete terms, Louis took many steps during his reign to amass power. He was to continue the practice set by his father Louis XIII (r. 1610-43) of never calling the States General, a centuries-old assembly of nobles that advised the Crown and authorized the levying of taxes. Louis XIV built a standing army and hence did not need to rely on his nobles to raise troops. He sold offices to nobles and ennobled wealthy men, appointing them to positions in his state bureaucracy. He asserted his authority over the clergy and religious orders, based upon a doctrine known as Gallicanism. By building roads and bridges and a national police force, Louis’s regime created conditions for commerce to flourish as never before. Louis’s power was certainly limited, and critics claimed that it was his bureaucracy, not he, that ruled France. Noble privileges remained; the parlements, or regional assemblies of nobles, continued to act as law courts, for example. But in Louis’s France the nobility’s status was far below what it had been in the Middle Ages. The influence in Europe of Louis’s enlightened absolutism was enormous. In Prussia, Austria, England, Russia, Sweden, and elsewhere, monarchs imitated France’s armies, administration, and arts and architecture.20

Enlightened absolutism, then, was a new idea in service of an old quest by monarchs to gather power. But it was not simply the eternal lust for absolute power cloaked in new words. The Enlightenment shaped absolutism by channeling it to the benefit of huge numbers of subjects. Louis XIV, Frederick the Great of Prussia, Maria Theresa of Austria, Catherine II the Great of Russia, and others used their enhanced power to advance science and technology so as to make their states and subjects prosperous.

Prior to the 1770s, the chief normative competitor to enlightened absolutism was constitutionalism, the theory that the monarch must be constrained by law as interpreted by ancient assemblies of nobles. In eighteenth-century Europe the nobility was understood not as an aggregation of individual aristocrats, but as a corporation, a body. Constitutionalism asserted that the old warrior caste had certain rights and privileges against the Crown and a crucial role as balancer between monarch and people. Constitutional polities could be quasi-republican, as in the United Provinces of the Netherlands, or monarchical, as in the case of England. Although Enlightenment thinkers such as David Hume and the Baron de Montesquieu were congenial to aristocracy, constitutionalism’s main appeal was not to the new learning but to medieval practice. Indeed, the nobles’ chief claim was that they had a right to their special status—as magistrates in their regions, as inheritors of government office and seats in provincial assemblies, as being exempt from taxes—because their ancestors had had those rights. To apply today’s political terms anachronistically, absolute monarchy was progressive, constitutionalism conservative.

For most of the eighteenth century the contest between absolutism and constitutionalism was more domestic than transnational, and had little effect on international politics. It was mingled with transnational Catholic-Protestant struggles in northwestern Europe in the seventeenth century—Catholics tended to be absolutists, Protestants, constitutionalists (chapter 4)—and as such contributed to the dynamics among France, the Netherlands, and the British Isles that issued England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the Wars of the League of Augsburg (1688-97). But there are few cases of one ruler forcibly intervening in another country on behalf of absolutism or constitutionalism, and little evidence of international alignments according to ideology. It seems that during these decades, absolutism and constitutionalism were not very competitive within countries, once the English and Dutch regimes were safe from France. Constitutionalist rulers faced little internal threat from absolutism; absolutist rulers faced little internal threat from constitutionalism.

Thus, in striking contrast to the French Revolution a century later, England’s 1688 revolution replacing a would-be absolutist with a constitutional regime did little to polarize European societies; it sparked no Continental uprising of nobles against monarchs. “Whatever its merit and shortcomings may have been,” writes one historian, “there was nothing in the distinctively British social order which could tempt foreigners to imitation.”21 Why was this? Historians make clear that on the Continent at the time, absolutism was succeeding on its own terms, terms set by the Enlightenment, terms themselves accepted for many decades by sufficient numbers of nobles and commoners. The France of Louis XIV was a spectacular success; its predictions for itself—prosperity, technological advancement, victory in war, cultural superiority—usually came true. As C. B. Behrens writes, enlightened absolutism “remained unchallenged … as long as the absolute monarchs seemed to provide more successful government than was to be had by other means.” It seemed superior to alternative forms of governments “by virtue of its ability to keep the peace at home and to mobilize men and money for national defence and aggrandizement.”22 England, in rejecting absolutism for constitutionalism, was simply peculiar.

As the eighteenth century progressed, however, absolutism did begin to fail on its own terms, leading to a reconfiguration of ideas, and of identities and interests, in the 1760s and 1770s. The chief difficulty with absolutism was its tendency to impoverish state and society. Already in 1748, Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws cautioned that what distinguished enlightened absolutism from despotism was that the former “permitted the existence of ’intermediate powers’,” namely the nobility as a corporation—something the Bourbons were not doing.23 By 1767 Voltaire, long an apologist for absolute monarchy, was favorably comparing the liberties of constitutionalist Britain to those of absolutist France.24 The English rejection of arbitrary power was gradually more appealing to aristocrats in France, in part owing to England’s manifestly superior ability to generate wealth. While the peasantries of the Continent were increasingly impoverished, that of England was increasingly enriched owing to its application of scientific methods to farming. Constitutional monarchy now appeared more adept at applying the new Enlightenment learning to the benefit of society. François Quesnay, leader of the Physiocrats, presented an idealized picture of England’s economy and argued in effect that “if France adopted the right policies, and became more like England, the French economy would grow and prosper.”25

The Seven Years’ War (1756-63) involved all the major powers of Europe and sharply increased states’ debts. In France, the Paris parlement tried to block extension of the war tax, asserting that the King (by now Louis XV, r. 1715-74) was bound by law, a claim that would have had force in Britain but that contradicted France’s absolutism. The parlement of Brittany tried to block the King from building a road without its permission. Parlements throughout the land began to coordinate, and declared that they constituted a general French parlement that retained the right to veto taxes or legislation. The nod to England’s constitutional regime was unmistakable. In 1766, an offended Louis XV rebutted the parlements, and in 1770 he abolished them and set up his own law-courts in their stead.26

Similar events took place in the absolute monarchies of Sweden and the Austrian Empire. In Sweden the aristocracy attempted to increase its domination of the Riksdag, and in 1772, Gustavus III (r. 1771-92), an admirer of French absolutism and former student of Voltaire, intervened to suppress the nobility.27 In the Habsburg lands of Hungary, Bohemia, Milan, and Belgium, the nobility resisted monarchical taxes; here the Empress Maria Theresa successfully suppressed aristocratic self-assertion.28 Even in England itself, exemplar of constitutionalism, the Whig or country faction had always suspected the rival Tories of being absolutists, and under George III (r. 1760-1820) the Whigs associated with the Marquess of Rockingham began to argue that the royal court was running roughshod over Parliament.29 Weak transnational ties are evident in these episodes. Montesquieu’s arguments about the necessity for an aristocratic check on monarchs were adopted by the Hungarian nobility in its struggle against the Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa (r. 1745-80).30

The aristocratic resurgence of the 1760s and 1770s was constitutionalist, not republican. Republics, upholding the old Roman Republic as a model, had existed in Europe since the Middle Ages—the Venetian Republic was founded in A.D. 727, and the United Provinces of the Netherlands was at least nominally a republic—but the nobles in most European lands wanted to retain a tamed monarchy. It was not until the 1770s that commoners began to turn toward republicanism. In European monarchies, commoners traditionally identified their interests with those of the Crown against those of the nobility. Theorists tended to justify monarchy based in part upon its ability to guard the commoners’ interests against aristocratic exploitation. As the eighteenth century wore on, tensions between commoners and aristocrats were aggravated by a decrease in upward mobility, as the practice of ennobling wealthy commoners (e.g., merchants) began to decrease.31 Gustavus Ill’s suppression of the Swedish nobility in 1771 inspired commoners in other countries to defy the aristocracy.32

But the legitimacy crisis in absolute monarchy was to produce a historical realignment in European and American politics. Starting with British North America, the upper strata of the commoners—merchants and professionals—began to turn against monarchs and to embrace republicanism.33 Like absolutism itself, this historic reconfiguration of identities owes much to the principles and consequences of the Enlightenment. The technology that enlightened monarchs put to use in public works and finance helped create the middle class and gave it more influence and self-consciousness. In addition, notwithstanding the early tendency toward absolutism in Enlightenment thinkers, the principle of holding all things up to the light of reason did not sit well, in the end, with any inherited or traditional authority. Monarchs, after all, inherited their seats just as aristocrats did. If all things are open to question, all institutions, especially those that have failed, are vulnerable. The upper strata of the commoners, and many among the nobility itself, began to question the privileges of monarchs as well as those of Church and nobility. Indeed, democratic and republican tendencies had begun to appear among the lumières in France, notably in the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It was Rousseau who located sovereignty not in the monarch but in the people or nation.34

It was across the Atlantic, in British North America, that commoners first declared themselves independent from their historic monarchical patron and established a new republic, inspiring commoners and nobles in other countries to become republicans and to form transnational networks.35

The insurrection in the thirteen colonies began, ironically, not as a republican movement but as a constitutionalist protest against what the colonial legislatures saw as a move toward absolutism in the Mother Country. Each colonial assembly, elected by the propertied classes, enjoyed “ancient” rights and privileges, including the exclusive right to tax the King’s subjects within the colony.36 A further irony was that it was Parliament, a fellow aristocratic body, that passed the Stamp Act in 1765, taxing the colonists over the heads of the colonial legislatures to pay off the Seven Years’ War. Seen plainly, the dispute was among constitutionalists over which aristocratic body—a colonial one or the Parliament at Westminster—had the power to tax the Americans

Thus, the discontented Americans met with some sympathy in England. The emerging Radical faction agreed with them that Parliament was an aristocratic despotism. The Rockingham Whigs asserted that Parliament did have the right to tax the colonists but favored rescinding the tax for practical reasons. But the Tories and the other Whigs in Parliament thought the American colonists must be taught a lesson. George III, needing revenue and concerned with principles of authority, agreed; King and Parliament closed ranks.37 The Crown-nobility coalition in Britain led to a predictable response in North America: by July 1776 the American Patriots, as they now called themselves, were blaming George himself for the injustices under which they claimed to suffer. From blaming the monarch it was a short step to blaming the institution of monarchy itself. In the hands of republicans such as Thomas Jefferson, the American Revolution pitted people against aristocracy and monarchy, democratizing Locke in a way that may not have pleased Locke himself.38 The Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776, declared the colonies “free and independent states,” that is, a republic.

But the British had to be driven from the United States before the latter could secure independence. The American armies met with mixed success in 1776-77. Louis XVI of France and his foreign minister the Comte de Vergennes badly wanted to avenge France’s loss to Britain in 1763 and to weaken the British Empire so that Louis could take his rightful place as, in the words of Orville Murphy, “the arbiter of Europe.” French and Spanish money subsidized the Patriots; then in 1778 a Franco-American alliance was signed and large French naval and land forces joined the struggle.39 The first forcible regime promotion of the second long wave was by an absolute monarch on behalf of republicanism. Louis and his ministers were acting out of concern for external security—to move the balance of international power in their favor—and in 1778 were not worried about any possible republican contagion into France.

Although the American Revolution was in a sense a conservative affair, intended to restore the constitutional order in the colonies, the establishment of a new republic was radical. Hence it attracted keen attention in northwestern and Central Europe and would contribute to the downfall of the French monarchy several years later. News from America was spread by returning soldiers, in Masonic lodges, and by various writers. The new U.S. state constitutions were translated and published in several European countries. Periodicals and reading groups already proliferating in the 1770s and 1780s became preoccupied with American events and tended to favor the revolution. Individuals mattered as well: Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson stimulated French enthusiasm for the Patriots, while John Adams did the same in the Netherlands; Adams even suggested that the Dutch burghers (commoners) ought to do as the Americans by reducing the power of the Stadtholder and the nobility. In effect, transnational ideological networks began to form over the republican revolution across the Atlantic. The American Revolution created an impression in many European societies, documented exhaustively by R. R. Palmer, that mankind had entered a new era of undefined liberation. A few monarchists and aristocrats began to fear that American events would inspire popular revolutions in Europe.40

Over the next few years, commoners in other lands began to follow the North Americans by distancing themselves from their longtime royal patrons and taking on the “patriot” label. In Spanish America creoles, or native-born elites, had become alienated from a new wave of émigré peninsulares or elites born in Spain; visitors and circulated documents from the young United States helped define an inchoate discontent with the Spanish monarchy.41 Jacques Pierre Brissot, a Frenchman who later was to lead the radical Gironde faction in 1792-93 (see below), visited America in 1788 and published an account in France extolling the virtues of popular sovereignty and in particular of a new constitution created by a popular assembly.42 Indeed, the various American state constitutions—all drafted and ratified by citizens’ assemblies, not aristocratic corporations—were published at least five times in France between 1776 and 1786.43

Demonstration effects from the American Revolution were strongest in the United Provinces of the Netherlands, a nominal republic with a Stadtholder as de facto head of state. The American constitutions also were published there and in 1787, the burghers and regents (nobility) coalesced against the Stadtholder William V, whom they accused of amassing excessive power. The progress of the Dutch revolution was strikingly parallel to that of the American: when the commoners began to demand too many concessions from the nobility, William saw his opportunity and sided with the latter. This historical realignment of (quasi-) monarch with nobility against commoners thrust the Dutch into a republican revolution. The Dutch Revolution of 1787 provoked another case of foreign regime promotion. Frederick William II, the King of Prussia (r. 1786-97) and an “enlightened” absolutist, sent 20,000 troops to help the Stadtholder (his brother-in-law) defeat the commoners.44 Although Frederick William desired influence in northwestern Europe, this invasion would have made little sense apart from the Dutch Revolution, itself a spillover from the American.

Far more famous and consequential was the French Revolution that erupted in July 1789. Like the Dutch, the French Revolution was not generated entirely by domestic events. French societal contacts with Americans and others had already been extensive,45 and the American and Dutch revolutions excited close attention in Paris. Palmer argues that Europe and the Americas during these decades were shaken by a general transnational democratic revolution that was manifest in various forms across countries. The great transnational movement cannot be reduced to class interests or material conditions. The northern British American colonies were commercial and smallholding; the southern, gentrified; France was an absolute monarchy with a subdued nobility; Poland (see below), a constitutional monarchy with an unusually strong upper nobility. Even so, revolutions in all these lands used similar language and symbols, appealed to similar sources, and were seen by friend and foe as being of a piece. The ideology itself was strong enough to obscure these differences and create common transnational bonds among very different types of elites

Like the American and Dutch revolutions, the French began as a constitutionalist revolt against absolutism. Louis XVI levied taxes to pay for a war—this time, ironically, French aid to the American patriots in the early 1780s. The parlements (regional noble assemblies) refused, and Louis’s May Edicts of 1788 reduced the parlements to judicial entities. At first nobility and bourgeoisie made common cause, openly demanding a constitutional monarchy of the sort advocated by Montesquieu. Louis backed down and the Paris parlement announced that the States General, comprising representatives of all three estates from throughout France, would meet for the first time in 174 years. A now familiar historic realignment took place: the French commoners (Third Estate) now began to assert themselves against both King and nobility; the latter two in turn began to make common cause against the “mob.” Advocates of popular rule, influenced by the writings of Rousseau, insisted that delegates to the States General not be segregated according to estate or rank; the nation must be one. Louis XVI rebuffed these egalitarians.46 The commoners, led by the Abbé de Sieyès, retaliated by announcing that they constituted a National Assembly with the authority to tax. On June 20, having been expelled by Louis, they gathered on a tennis court to pledge that they would write a new constitution for France. Louis proposed a compromise, but the Assembly refused; Louis responded by mobilizing troops around Versailles and Paris. Word reached the countryside and peasants began seizing nobles’ property. Commoners seized the city government in Paris on July 14 and organized a national guard.47

All during these weeks, and throughout the French Revolution, French elites interacted with keenly interested foreigners. Émigrés—aristocrats and clergy—fled to neighboring lands, told (often exaggerated) tales of depredations by mobs, and urged foreign intervention to halt the spread of the democratic cancer that threatened thrones and nobility alike. At the same time, thousands discontented with the status quo in their homelands flocked to France to participate in the stirring events, much as Protestants converged on Calvin’s Geneva in the mid-sixteenth century (chapter 4). They founded their own societies and publications and plotted revolutions for their countries. As with the American Revolution, printing presses spread the word rapidly. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of August 1789, itself influenced by the U.S. Declaration of 1776, was translated into a dozen languages and disseminated throughout Europe.48

In Poland, which had already been in the midst of a parallel movement to weaken its powerful nobility, reformers were electrified by news from Paris. As Palmer writes:

Conscious of a revolution in their own midst, learning excitedly of the one in Paris, and remembering the one in America at the opposite extremity of Western Civilization, where Kosciusko and Pulaski and a dozen others had fought, the Poles formed an impression of revolution on a worldwide scale.49

In November the burghers (upper stratum of commoners) in 141 Polish towns petitioned the diet that they be allowed political representation. The diet, entirely aristocratic, was alarmed: even the reformers had not wanted the commoners to have direct power. Still, within a year it had passed reforms; the Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791, strengthened the burghers and was taken by people of all ideological stripes as an extension of the French Revolution.50

Even in constitutionalist England some Whigs, convinced that George III was amassing power, declared that their country needed to imitate France. The Unitarian pastor Richard Price declared his hope that Britain’s parliament would follow the French example and become a national assembly:

Be encouraged, all ye friends of freedom, and writers in its defense! The times are auspicious…. Behold kingdoms, admonished by you, starting from sleep, breaking their fetters, and claiming justice from their oppressors! Behold, the light you have struck out, after setting AMERICA free, reflected to FRANCE, and there kindled into a blaze that lays despotism in ashes, and warms and illuminates EUROPE!51

Thomas Paine wrote his fellow Whig Edmund Burke that, “The revolution in France is certainly a Forerunner to other Revolutions in Europe. —Politically considered it is a new Mode of forming Alliances affirmatively with Countries and negatively with Courts.” But Burke, longtime defender of constitutional monarchy, saw incipient republicanism in these assertions of popular sovereignty, and responded with his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), a polemic and prophecy against the revolution.52 So began a Herculean effort by Burke and his followers to unite Britain’s constitutional monarchy to the absolute monarchies of Europe in an anti-revolutionary front.

At first most European monarchists were not as alarmed as Burke by events in France. Through the middle of 1791 it was not clear to all that the revolution threatened Europe’s entire sociopolitical order, including monarchy itself. Both Joseph II (r. 1765-90) of Austria and his successor Leopold II (r. 1790-92) were enlightened absolutists, accustomed to thinking of the commoners as their allies. They blamed the hapless Louis XVI for being insufficiently enlightened.53 The only monarch who seemed particularly frightened was Gustavus III of Sweden, who as noted above had put down his own aristocratic revolt in the previous decade. In June 1791 Gustavus, alarmed at the confinement of Louis and Marie Antoinette, helped arrange their escape from France. The royal Flight to Varennes failed and the King and Queen were returned to Paris. With the humiliation of King and Queen, monarchists—absolute and constitutional—throughout Europe began to see a broader danger and a need for cooperation.54 In August, Leopold of Austria and Frederick William of Prussia issued the Pillnitz Declaration, calling for concerted action in France by the other great powers.55 In Paris, the suspicion spread that an international conspiracy of nobles and monarchs was planning to overturn the revolution.

In September 1791 Louis submitted to France’s new constitution. The country now joined Britain as a constitutional monarchy. Transnational ideological polarization continued between revolutionaries and absolute monarchists within and without France. Brissot, publicist of the American state constitutions, argued in the National Assembly in Paris that an international monarchical conspiracy was trying to overturn the revolution, and that France should attack Austria because patriots in Habsburg-ruled lands would rise up and help the French. In response, Leopold and Frederick William formed an offensive alliance in February 1792. In March, Gustavus of Sweden was assassinated, stoking monarchists’ fears of a transnational republican conspiracy. On April 12, Vienna moved 50,000 troops to the frontier. On April 20, the Legislative Assembly in Paris declared war on Austria.56

A second regime change took place in France in September 1792: the National Assembly abolished the constitutional monarchy and declared France a republic. The British government of William Pitt concluded that the French could not be negotiated with and might try to “liberate” the crucial United Provinces, now a constitutional monarchy whose republicans had already asked for French intervention. The French foreign minister accused the British of stirring up counter-revolution in France, and on February 1, 1793, the Convention unanimously declared war on Britain and the United Provinces.57

The War of the First Coalition (1792-97) exacerbated transnational ideological polarization by making patriots more patriotic and by causing constitutional and absolute monarchists to coalesce. In Poland, England, Scotland, Ireland, Belgium, the United Provinces, Switzerland, and parts of Italy and Germany, patriots declared common cause with their counterparts in France. Jacobin and other pro-French societies appeared in England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and the United States. “The Masonic lodges,” writes Palmer, “also provided a kind of international network of like-minded people. Their existence facilitated the circulation of ideas.” In some of these lands patriots rose up and attempted revolutions of their own.58

The 1791 Polish Constitution, inspired by events in France, was not republican. It was rather a more democratic constitutional monarchy, in which the landholding nobility lost power to the burghers and peasantry. The Polish nobility quickly revolted and asked Catherine of Russia to send troops to overturn the new regime. Catherine had two powerful reasons to intervene: the new constitution promised to strengthen Poland against foreign (Russian) influence by binding monarch and burghers; and it seemed evidence that French “démocratisme” was a spreading virus. As an Austrian minister wrote three years later:

One sees in [Poland] strictly the pattern of the French Revolution, and that it is from the hearth of Paris that the spark has come which had enflamed Poland and which will incinerate all of Europe … [I]t is war to the death between sovereignty and anarchy, between legitimate government and the destruction of all order.59

Upon hearing that France had declared war on Austria in 1792, Catherine did indeed order an invasion of Poland to “restore the original constitution.” The Polish King asked Frederick William to counter-intervene to protect Polish independence from Russia. Notwithstanding his enduring interest in containing Russian power, on June 8, Frederick William refused. Then in January 1793, he sent an army to Poland to join the Russians, declaring that Polish patriots were spreading the revolution to his domains. Within a week, Catherine and Frederick William had agreed to a second partition of Poland.60

The restoration of the old regime was met with a resistance movement among burghers in Warsaw; even some nobles, angry at Russo-Prussian intervention, joined. Poems and songs from the time make clear their Jacobin and Patriot inspiration. The leaders chose Kosciuszko, military leader of the 1792 resistance (and veteran of the American Revolution), then in France, as their leader. In 1794, Kosciusko returned to Poland, declared the serfs free, and led a force against the Russian and Prussian occupiers. Polish rebels composed a Catechism of Man:

France is our example,

France will be our help;

Let cries of Liberty and Equality

Resound everywhere.

Let us follow in her footsteps…

Let the nobles and lords disappear

Who would deny Fraternity to the people?61

Catherine and Frederick William were also genuinely alarmed at a Jacobin-style contagion from Poland. The King of Prussia wrote to his ambassador in Vienna, “I feel keenly how essential it is to crush in its germ this new and dangerous revolution, which touches so closely on my own states, and which is also the work of that diabolical sect against which a majority of the powers have combined their efforts.” Wrote Catherine to her leading general, “for the good of Russia and the entire North she had to take arms against the wanton Warsaw horde established by French tyrants.”62 The Russians and Prussians prevailed in October 1794, and Kosciuszko was taken prisoner. Austria joined Prussia and Russia in yet another partition of hapless Poland.

Acquiring Polish territory was of course a traditional interest of Russia and Prussia; it is not necessarily the case that Tsarina and King were acting chiefly out of ideological motives.63 But the Russian and Prussian actions make little sense without the existence of transnational republican networks. Those anti-monarchical networks gave Catherine and Frederick William, normally rivals, a common interest in overturning popular sovereignty in Poland. Had these networks not existed and been swollen by the events in France, it is likely that no foreign intervention would have happened.

The great-power war between France and the monarchical coalition of great powers fed back into transnational networks, further polarizing European and even American elites along ideological lines. In Latin America, creoles who had been impressed with Enlightenment writings and the formation of the United States were split by the violence and anti-clericalism of the French Revolution. A particular fear of creole slaveholders was that the Haitian revolution of 1791, which was propelled by a slave revolt and resulted in the abolition of slavery, would infect their lands.64 In the United States, events in France aided in the polarization that eventually resulted in the formation of the two political parties, the Federalists and Republicans. The former were hostile toward the French Republic, the latter sympathetic or enthusiastic.65

In Europe this polarization gave the warring governments powerful incentives to carry out ex post promotions during the war. Rulers may not have invaded countries simply in order to alter their domestic regimes, but they did find in case after case that regime promotion was an efficient way to make the target into allies. Regime promotion made sense precisely because of transnational ideological polarization: elites across Europe were either intensely republican and pro-French, or intensely monarchical and anti-French. In late 1794 the British, having occupied the island of Corsica, found a sympathetic leader in Pasquale Paoli. Corsica had been annexed by France in 1770 and Paoli had fled out of hatred of the absolutist Bourbons. But the Reign of Terror of 1793 turned him against the Jacobins as well, and he sought British help in establishing the constitutional Kingdom of Corsica, a constitutional monarchy aligned with Britain.66

On the Continent itself the French armies did likewise, establishing republics in the lands they conquered. In 1795, they invaded the United Provinces of the Netherlands and, cheered by the Dutch patriots, ousted the Stadtholder and set up the Batavian Republic.67 The following year in Bologna and the surrounding region, the French set up the Cispadane Republic.68 In 1797, they established the Ligurian Republic in Genoa and the Cisalpine Republic in northern Italy.69 The next year they made Switzerland into the Helvetic Republic and set up a Roman Republic.70 In 1799, the French remade Naples into the Parthenopæan Republic.71 In each of these, the revolutionary French armies were welcomed as liberators by the patriots they had inspired. But as Blanning writes, they were not simply examples of French revolutionary zeal. “One of the most inspired inventions of revolutionary politics …turned out to be the satellite state, a device for maximizing international control with a minimum of metropolitan effort. Puppet monarchs were nothing new in European history of course, but the satellite republic, which combined the appearance of altruism with the reality of control, was an invention with a glittering future, destined to reach its climax in post-1945 Eastern Europe.”72

Although the conquest of these smaller countries was instrumental to the war, the imposition of constitutional monarchy by Britain or republicanism by France was no mere afterthought. These powers could have left the existing regimes in place and coerced or bribed leaders to do their bidding. Faced with such intense transnational ideological polarization, they could not afford to do so.

The revolutions, wars, and regime promotions of the 1790s failed to resolve the transnational struggle among absolute monarchy, constitutional monarchy, and republicanism. Each ideology retained strong advocates across several countries at once in Europe, and each retained at least one great-power exemplar. In France itself, however, republicanism was metamorphosing. It had turned from Left to Right in 1795 with the Constitution of the Year III and assumption of power by the five-man Directory. In November 1799 Napoleon Bonaparte, the country’s most successful general, carried out a coup d’état and made himself First Consul. Napoleon had saved the revolution with his military victories, but he feared the revolution all the same. So began the French Republic’s slide into the hybrid regime—rationalist, absolutist, imperialist—whose ambiguity complicated the ongoing transnational ideological struggle.

During his years as First Consul, Napoleon continued to enjoy the good opinion of most “enlightened” elites in Europe and the Americas. He rationalized public administration and law in France and in the lands he conquered. It was his self-coronation as Emperor of the French in 1804 that changed the opinion of many. Bonaparte deliberately designed the coronation to appeal to symbols of the ancien régime; it took place at Paris’s Cathedral of Notre Dame, with the Pope present. Ludwig van Beethoven had so admired Napoleon that he had dedicated his pathbreaking Third Symphony to him; upon hearing the news of Bonaparte’s self-coronation, so goes the story, Beethoven was so infuriated that he tore up the dedication. In South America, Simón Bolívar, who had once idolized Napoleon as “the bright star of glory, the genius of liberty,” turned against him.73 Bonaparte was to go further. In 1808, he created his own nobility by endowing his generals with titles and land, just as the Bourbon monarchs had ennobled favored wealthy subjects.74 The designation of the French state, “French Republic, Emperor Napoleon,” captures the incoherence of the Bonapartist regime.75

Thus, Napoleon split both monarchists and republicans within France and across Europe. For some monarchists, absolutist or constitutional, his complete lack of any blood title to any throne made him forever an illegitimate ruler. These monarchists began to adopt the label legitimist to distinguish ancient dynasties from Bonaparte’s upstart Corsican family. For other monarchists, Napoleon was acceptable: he had restored many elements of the old order in France and was doing so in the lands he conquered. Republicans, too, were divided. Some continued to insist that, for all of his flaws and betrayals, Napoleon remained preferable to his enemies, the advocates of absolutism, who sought to re-impose their regime in France and indeed in Britain.76 In the United States, Thomas Jefferson called Napoleon a “republican emperor” and considered France a more natural friend than Britain of the American Republic.77 In general, however, Napoleon’s gradual self-aggrandizement from 1799 disillusioned and becalmed many who had identified with the French Republic.78

Confusion and ambiguity aside, that the First Empire was Europe’s leading power for so many years, and an aggressive one at that, meant that Bonapartism was a contender in the grand ideological struggle. France’s unexampled power and glory gave Bonapartism a degree of transnational appeal. Once he conquered and occupied a foreign power, Napoleon faced the usual choice as to how the target was to be governed: leave the current regime in place, let matters take their course, or install a new regime. In most cases, Napoleon did as rulers typically do in a time of transnational ideological polarization: he imposed his own institutions, in what I call ex post promotions. As Michael Broers writes, “Napoleonic rule usually entailed the introduction, in whole or in great part, of the uniform, highly centralized system of administration and justice that had evolved in France since the Revolution of 1789.”79 In 1800 in Bavaria;80 in 1801 in Tuscany;81 in 1803 in the Cisalpine Republic (renamed the Italian Republic, then the Kingdom of Italy in 1804) and the Helvetic Republic (renamed the Helvetic Confederation);82 in 1804 in northwestern Germany, renamed the Duchy of Berg;83 in 1805 in Naples, Lucca, and the Batavian Republic (renamed the Kingdom of Holland);84 in 1806 in Neuchâtel, Baden, Württemberg, Nassau, and Spain;85 in 1807 in more parts of Germany (renamed the Kingdom of Westphalia) and in Poland (renamed the Grand Duchy of Warsaw);86 in 1810 in Frankfurt:87 Napoleon imposed various of his institutions. (Ironically, under the Franco-Austrian Treaty of Lunéville of 1801, Vienna agreed not to alter the regime of any of France’s satellite states.)88 French troops would typically divide a country into prefectures, establish modern salaried bureaucracies with responsible chiefs (rather than nobles), and rationalize the tax system. The new governments would seize lands belonging to the Catholic Church and remove all religious discrimination.89 The Napoleonic Code and gendarmeries to safeguard travel in the countryside increased the well-being of the average European. They also made the French war machine more efficient, since Napoleon used the human and material resources from these lands to conquer or retain more territory.90

It was in many of these conquered lands that liberals felt most betrayed by Bonaparte. In Spain, where Napoleon placed his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the throne in 1808, liberals were perhaps the most difficult. Some, labeled afrancesados, worked with Joseph at first to craft a new constitution that reduced the power of the Church and recognized some civil liberties. Other liberals worked against the Bonapartists, and in 1812, when they dominated the Cortes or national legislature, ratified (under British protection) a liberal constitution.91 The Constitution of 1812 became a touchstone for southern European and Latin American constitutional monarchists for decades to come.92

Indeed, the war on the Iberian Peninsula inspired powerful independence movements in Latin America that looked to the American and French revolutions for inspiration. The French invasion of Portugal in 1807 led the Prince Regent, later to become King John VI, to flee to Rio de Janeiro. By 1815, John had declared Brazil a kingdom co-equal with Portugal. Spain’s colonies were set aflame by news that Napoleon had captured Ferdinand VII. Much like the upper strata of the commoners in Europe and the landowning and professional elites in British America, creoles had long chafed under the domination of peninsulares, émigrés born in Spain. Across Spanish America, creoles, usually in cabildos or city councils, declared self-government. Over the next two decades Spain was to fight to keep or recapture its colonies. The two outstanding military leaders of the independence movements were José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar, both of whom had spent part of the first decade of the century in Europe absorbing the new ideas.93

In the meantime, the British were not immune to the lure of their own fellow constitutionalists in foreign lands. Sicily was ruled by Ferdinand, a Bourbon absolutist. Sicilian barons had always resented absolutism, and as the war continued they came to admire the British constitutional model. Some began to call for a British invasion, and in 1811 the British obliged. The following year the British overthrew Ferdinand and replaced him with his son Francis, who ruled under a constitution modeled on the British.94

The Congress of Vienna (October 1, 1814-June 9, 1815) was in many senses a “founding moment” for the international system, inasmuch as it created institutions for preserving order among the great powers.95 Those institutions also involved domestic regimes. After defeating Napoleon, the rulers of the victorious powers had the usual problem of how to reconstruct order in the liberated lands. They might have left intact the Bonapartist regimes. They might have done what Alexander of Russia preferred in the case of France itself, namely to oust the rulers and let the people (however defined) decide what sort of regime they would have.96 Or they might have imposed regimes. In the crucial French case they chose the third option, restoring the House of Bourbon and using the leverage from the occupation to set up a new regime. The powers were divided as to whether France’s monarchy was to be absolute (favored by Metternich of Austria) or constitutional (favored by Castlereagh of Britain). In the end, they settled on an ambiguous compromise.97 In 1814, the French Senate and provisional government made clear that they were inviting Louis to become King, imitating the English Parliament’s invitation to William of Orange in 1688. Louis made equally clear that he was King by divine right. The Constitutional Charter of June 4 reflects the ambiguity: the King was bound to follow it, and it allowed the usual Enlightenment list of civil liberties; but he retained broad powers, including the initiation of legislation, supreme command of the armed forces, and the right to dismiss both national Chambers. French elites were divided accordingly, and for the next several decades power oscillated between the absolutists and the constitutionalists, with Bonapartists and republicans also having a presence in the legislature.98

In Switzerland, too, the governments of the powers imposed a constitution, essentially restoring the old regime of cantonal confederation. The Swiss constitution was included in the Final Act of Vienna and the cantons were coerced into accepting it.99 In all other liberated states, however, the victors chose the second option, allowing the polities—meaning the elites—to set up regimes of their choosing. As Paul Schroeder writes, for the allied governments, “[m]onarchy was the unchallenged basis of constitutional doctrine and the foundation of political community.”100 Indeed, delegates to the Congress of Vienna were far from indifferent concerning domestic regimes. The consensus was that the destructive quarter century of great-power war that had just ended was caused by the revolution in France that had inevitably evolved into Napoleon’s aggressive imperialism. The solution thus must include the restoration of “legitimate” monarchies, dynasties that held power owing to ancestral rights, throughout Europe. The world, so thought the delegates at Vienna, could resume its normal stable order, free of metastasizing revolutionary regimes.101

But the victors knew that, to their good fortune, elites in the lands the French had conquered wanted to restore monarchy. Beyond that, they left those elites to work out their institutions. In some states, such as those of southern Germany, elites chose constitutional monarchy. In others, such as Spain and most Italian states, they chose absolute monarchy. Within the latter category elites varied according to how far they retained the various institutional reforms brought by the French armies. On the whole, however, it is remarkable how tolerant the great-power governments were concerning post-Napoleonic regimes.102 (It is also important to note that in Germany the status quo ante bellum concerning political territorial boundaries could not have been restored without great coercion. In 1806, Bonaparte had replaced the old Holy Roman Empire with the Confederation of the Rhine, reducing Germany’s states from more than 300 to approximately forty; the rulers of the forty naturally preferred to keep the new arrangements.)103

Beneath the restorations, however, the transnational crisis over political legitimacy remained. What C. W. Crawley writes about Frenchmen was true throughout the Western world: “the ’Great Schism’. created by the events of the 1790s was not easily healed.”104 The Revolution was not merely a memory or symbol around which to rally conservatives. It was still present as potential energy running through the societies of an exhausted Europe. Discontent with the restorations was wide, deep, and diverse. Some of the discontented were constitutionalists, others republicans of various degrees of radicalism; and in France, Bonapartism remained a force. Revolutionaries remained quietly mobilized in secret societies and Masonic lodges and worked to bring about another cataclysm. They were motivated by a strong notion of historical progress. The years 1789-94 had shown what was possible even against powerful monarchs and armies; what Geoffrey Best calls the “insurgent underground” in Europe was convinced that it could happen again, with permanent results.105 What is sometimes broadly called the Left was divided—republicans against constitutionalists, for example—but as seen below, the Left could unite when a revolution somewhere in the system sparked demonstration effects across societies.

In similar fashion, the post-Napoleonic political Right was divided but could coalesce when faced with revolution. Conservatives favored gradual reform of traditional institutions, while reactionaries insisted on restoring what they imagined to be the old regime. What these had in common was the conviction that, having expended vast amounts of blood and treasure to defeat Bonaparte, they must not allow more revolutions. Indeed, monarchists began to turn away from the Enlightenment, now blamed for the catastrophes of the preceding decades, and toward more traditional Christian foundations for monarchy. From now on, the Enlightenment was identified not with absolutism, as in the eighteenth century, but with constitutionalism and republicanism.

Some ruling elites were perpetually terrified of revolution. The most prominent was Metternich. Knowing that the Habsburg Empire he defended was, in the words of Frederick Artz, “merely a governmental machine without any genuine national basis,” Austria’s Minister of State saw that “the mere introduction of democratic or nationalist ideas anywhere in Europe could easily stir up disruptive movements in [Austria]. Hence, revolutionary ideas in speeches, books, or newspapers frightened Metternich, even if they appeared as far away as Spain, Sweden, or Sicily.”106 That dynamic implicated international stability or the balance of power.107 For example, the power of Austria, an absolute monarchy, depended in part on Habsburg influence in Italy. Should one or more states in Italy switch to a republican or constitutionalist regime, it would almost certainly become anti-Austrian, inasmuch as, in the current highly polarized atmosphere, constitutionalists and republicans abhorred Austria as an exemplar of absolutism. Revolutions in Italy would weaken Austria from within and without and would upset the delicate balance of power. Consequently, all the powers had an incentive to preserve absolute monarchy in Italy.108 As seen below, when revolutions erupted and the Right rallied against them, the Left across states would coalesce into what Eric Hobsbawm calls “a single movement—or perhaps it would be better to say current—of subversion.”109

The restorations accomplished, the rulers of the great powers—with the exception of Tsar Alexander—began to settle into what they thought would be normal times. In 1818, representatives of the four allies plus France conferred at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) to normalize relations with France. Alexander, attending in person, had by now become even more fearful than Metternich of transnational revolution, and proposed a permanent alliance that would overturn revolutions wherever they might arise in Europe. The Prussian and Austrian delegations were sympathetic, but Castlereagh of Britain was adamantly opposed. In the end, Alexander’s proposal was defeated, as Metternich was concerned about the extension of Russia’s reach into Central and Western Europe. Instead, the governments invited France to join a Quintuple Alliance and pressed its government to suppress republicanism within its own borders.110

An eruption of rebellion and revolution across Europe in 1820 provoked transnational ideological repolarization, and triggered a short wave of forcible promotion. First in Spain, then in Portugal, Naples, Piedmont, and Greece, subjects attempted to force kings to submit to liberal constitutions. When news of the Spanish rebellion reached Spanish America, the fledgling states of Gran Colómbia, Venezuela, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, and Mexico all adopted constitutions patterned after the Spanish Constitution of 1812.111 In France, the King’s nephew was assassinated. Even in Britain, where the government had lately suppressed Radical dissent, attempts were made on the lives of cabinet members. The seemingly premeditated and coordinated nature of these outbreaks gave new life to Alexander’s anti-revolutionary proposal from two years previous. The Troppau declaration of November included the following:

States which have undergone a change of government, due to revolution, the results of which threaten other states, ipso facto cease to be members of the European Alliance, and remain excluded from it until their situation gives guarantees for legal order and stability. If, owing to such alteration, immediate danger threatens other states, the powers bind themselves, by peaceful means, or if need be by arms, to bring back the guilty state into the bosom of the Great Alliance.

In January 1821, the great-power conference moved to Laibach (Ljubljana), where the governments of Russia, Prussia, and Austria agreed that Austria would unilaterally overturn the revolutions in Naples and Piedmont. In March 1821, an Austrian army marched toward Naples and, sustaining very few casualties, overthrew the new constitutional monarchy the following month. A similar Austrian action in Piedmont had similar results.112

More domestic regime imposition was to come. In France the absolutist party did well in 1820 elections, and the next year the absolutist government began moving France in its ideological direction, censoring criticism of the government and suspending habeas corpus. In 1822, Spanish absolutists rebelled against their country’s new constitutional regime, which by then had greatly weakened King Ferdinand, and the Russians again began calling for joint intervention to restore absolute monarchy in Spain. The French government posted an army of observation along the Pyrenees. At the Conference of Verona in November, France, Austria, Russia, and Prussia agreed to French intervention in Spain on behalf of the absolutists. In April 1823, a 100,000-man French force marched to Madrid and Cadiz and restored Ferdinand’s absolute rule in a nearly bloodless counter-revolution.113

The one great power to abstain from all of these declarations and actions—Troppau, Laibach, and Verona—was constitutionalist Great Britain. A British delegate attended Troppau as an observer only, and back in London Castlereagh deplored the declaration, “condemn[ing] the claim that the Alliance had the right to put down revolutions anywhere.”114 In a famous Cabinet State Paper of May 5, Castlereagh condemned the very notion of external intervention in any country’s domestic regime. The alliance was “never intended as a union for the government of the world or for the superintendence of the internal affairs of other States.” Calling attention to Britain’s distinctive constitutional nature, the Paper added: “No country having a representative system of Government could act upon [such a general principle].”115

Many historians have taken Castlereagh at his word: Metternich, Alexander, and the others were interventionist, but Britain was not.116 In fact, as had been seen during the Napoleonic wars, the British had no objection to foreign ideological intervention per se; it was intervention on behalf of absolutists to which they objected. In the contest between absolutism and constitutionalism that continued to thread across Europe, Britain stood to lose influence from the spread of the former. Non-interventionism was a British rhetorical strategy against absolutist France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia.

Thus, what happened in 1826 in Portugal, traditionally a British ally, comes as little surprise. The 1820 Portuguese Revolution (which followed that in Spain) had produced a constitutional monarchy under King John VI. In March 1826 John died, and constitutionalists and absolutists in Iberia, Latin America, and much of Europe polarized over the succession. A concord between absolutists in Spain and Portugal led to a Spanish invasion of Portugal and the enthronement of Dom Miguel as absolute monarch. Constitutionalists in Lisbon appealed to London for help. By this time absolutists dominated French politics. Under Charles X since 1824, the French government had restored property to the émigrés of the Revolution, mandated capital punishment for sacrilege, and increased tax revenues to the Church.117 With transnational politics so polarized, an absolutist Portugal would surely align with absolutist France. In December, a small British force easily defeated the Portuguese absolutists and restored the constitutional regime under Pedro IV.118 Portugal was returned to the British sphere of influence.

As regimes stabilized in the 1820s, the incidence of forcible regime promotion decreased sharply. Yet, transnational republicanism and constitutionalism retained their potential to polarize societies and rulers. In 1830 began yet another wave of rebellions and revolutions, this one more serious than that in the early 1820s, in part because this time the first revolution was in France itself. The wave alarmed absolutists and presented opportunities to constitutionalists; both transnational groups stepped up their cooperation and hence polarization.

France’s Charles X (r. 1824-30), successor to Louis XVIII, had begun to move his country further toward absolutism. Liberals began to counter-mobilize, and in July 1830, a coalition of liberals gained a majority in the Chamber of Deputies. The absolutist Prime Minister responded by dissolving the Chamber, reducing the electorate by 75 percent, and outlawing publications not approved by his government. A liberal revolt began in Paris and by July 30, rebels had taken the city. Charles abdicated in favor of his grandson Henry. But Henry never took the throne, and republicans and constitutionalists fought over what form the new regime would take. Republicans wanted the aged Marquis de Lafayette to be President, but constitutional monarchists wanted a new King, Louis-Philippe, the Duke of Orleans. The latter prevailed as Louis-Philippe and Lafayette embraced publicly. Louis-Philippe disavowed the divine right of kings and declared himself a “Citizen-King,” a constitutional monarch on the British model. The July Monarchy abolished censorship, separated state from church, and expanded the franchise.119

The July Monarchy inspired liberals to rise up in Belgium, Switzerland, the German Confederation, Italy, and Poland. On August 25, Belgian nationalists, chafing against Dutch rule under the 1815 settlement and inspired by the late events in France, began demonstrating in Brussels and provincial towns. King William agreed to call the States General; in October that body declared Belgian independence. The governments of Austria, Prussia, and Russia, the three eastern absolutist monarchies, asked the government of France to support an intervention to restore the authority of the Dutch King in Belgium. But Louis-Philippe’s government refused and instead joined the government of fellow-constitutionalist Britain in supporting the Belgian insurrectionists

Rumors of a great-power war spread, leading the British and French to invite the three eastern powers to join them in hammering out a Belgian settlement. The great-power talks were hampered by the very transnational polarization that propelled the crisis: the French were at pains to appease domestic liberals who sympathized with the Belgians, while the Austrians and Prussians feared that Belgian success would exacerbate liberal fervor in the German Confederation. In the autumn of 1832, the Dutch King William invaded Belgium to re-establish control. The British and French governments responded with a joint military-naval intervention. The rulers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia did not counter-intervene, but were increasingly alarmed at this western liberal alliance; in Prussia “semi-liberal pro-Westerners” were ousted from the government for being a sort of Fifth Column.120

Italy was home to several liberal secret societies with contacts in France and Belgium. In February 1831, as a direct consequence of events in the latter, revolutions erupted in Modena, Parma, and the Papal States, all replacing absolute with constitutional monarchies. The liberals knew they risked provoking an Austrian intervention, since Habsburg rule in northern Italy was at stake; but they counted on their hero Louis-Philippe to rescue them. In the following month Austrian troops marched into the states, easily defeated the armies of the new governments, and restored the absolute monarchies. Louis-Philippe responded by mobilizing a force of 80,000. A five-power conference was convened in Rome in April to avert war. It failed, and the following February a French force landed in the Papal States and began to stir up liberals. In the meantime, in Piedmont a new King, Charles Albert, declared for absolutism, entered a treaty with Vienna, suppressed the secret societies, and broke relations with the constitutional regimes in Spain and Portugal.121

Within the German Confederation, liberals in Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, Nassau, Brunswick, Hanover, Electoral Hesse, and Saxony responded to the French Revolution of 1830 with their own uprisings. In May 1832, at least 20,000 liberals gathered at Hambach and called for a united German democratic republic. Discontent in Germany was not simply with absolute monarchy but with the Austrian hegemony that kept it in place. Prussia, which had some reform-minded ministers, might have exploited the uprisings to weaken Austria. In the event, however, the unrest drew the two absolutist governments closer together. King Frederick William of Prussia fired his leading liberal minister and ordered cooperation with Metternich in suppressing the revolutions. Berlin and Vienna worked in concert to pressure the Diet at Frankfurt (the council of the German Confederation) to pass the Six Acts in June and July, censoring the press and handing a measure of power from parliaments to princes in the German states. Britain and France, the constitutional great powers, protested, but the absolutists prevailed.122

Indeed, the Prussians, Austrians, and Russians cooperated in Poland despite their Realpolitik rivalries. Poland was ruled by Russia at the time, and Tsar Nicholas ordered Polish troops in Warsaw to ready themselves to march westward to overturn the revolution in France. Liberal Polish officers rebelled. The Russian viceroy left for Lithuania with his garrison, and in early February 1831 the Polish diet declared Nicholas deposed. Nicholas responded with force. The Polish patriots had thought that Austria, Russia’s rival, would intervene on their behalf. But Metternich, fearing liberal revolutionary contagion, advised the Poles to submit to the Tsar. The Prussians actively aided Russia by disarming Polish rebels who crossed into their territory. The French proposed to Britain a joint offer of mediation.123