Overview of Chinese Painting

Traditional Chinese painting, which originated in the Han Dynasty (206 BC–AD 220), is completely different from western painting in terms of style and concept. This long-established art form mainly comprises ink or color applied with a brush to a piece of silk or xuan paper, which is then mounted on a hanging scroll.

Chinese painting has a long history. Silk paintings can be traced back to the Warring States Period (475–221 BC), before paper had even been invented. The most famous of these is A Man Riding a Dragon (fig. 7). The line arrangement on the silk cloth has become one of the most common techniques and characteristics in Chinese painting nowadays.

Chinese painting falls into three categories: figure (fig. 8), landscape and bird-and-flower. The objects in figure and landscape paintings are comparatively straightforward, whereas those of bird-and-flower painting are much varied and include flowers, birds, fishes, insects, animals and still lifes.

The history of Chinese figure painting is very long. The earliest unearthed colored pottery from the New Stone Age already demonstrated figure painting, and prehistoric period rock art also showed many figure images. The earliest stage of figure painting simply presented two-dimensional lines. Until the period of Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern dynasties (220–589), the quality of figure painting had been pronouncedly advanced. In the Sui Dynasty (581–618), Tang Dynasty (618–907) and the Five Dynasties (907–960), figure paintings featuring fine brushwork and heavy color continued to progress in complexity. In the Song Dynasty (960–1279), line drawing was introduced. In the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), figure painting began to transform. The evolution continued in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) and Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), fusing with western realism and expressionism, and generating many new ideas and techniques.

Fig. 7 A Man Riding a Dragon

Warring States Period

Silk painting

Height 37.5 by width 28 centimeters

Hunan Provincial Museum

Unearthed from the Chu Tomb of Danziku, Changsha, Hunan Province, China in 1973. In this painting, a man in a robe holds a sword and stands sideways atop a dragon’s body beneath a canopy. The dragon’s head is tilted upward and its tail is curled, its body forming a boat. The fluttering robe and canopy tassels indicate the direction of the breeze, showing the dragon boat moving forward along with the breeze. The man is drawn vividly with a detailed face. The presentation of his robe is smooth, depicting its soft texture and elegance. This is a representative figure painting from ancient China.

Fig. 8 Copy of Gu Hongzhong’s Night Revels of Han Xizai (detail)

Song Dynasty (960–1279)

Anonymous

Ink and color on silk

Height 28.7 by length 335.5 centimeters

Palace Museum, Beijing

This painting captures the activities at a dinner banquet of Han Xizai, an official of the Southern Tang Dynasty (937–975). The entire painting is divided into five scenes and the one on the left is the fourth scene. Han unties his robe and sits cross-legged on a chair to listen to an instrumental ensemble of five women. All the figures, whether main or supporting characters, are vividly and accurately depicted. The painting is colorful and neat with sophisticated line work. Different objects are portrayed in different techniques to illustrate the variations. This is one of the most precious paintings from ancient China.

Landscape painting (fig. 9) is the most representative form of Chinese painting. It first sprouted in the period of Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern dynasties and officially became a branch of Chinese painting in the Sui Dynasty. With unceasing development, it reached its first peak in the Five Dynasties and Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127). The unique skills, methods and styles it encompassed made it the most dominant form of Chinese painting in later ages. The second peak appeared in the Yuan Dynasty. Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322), a famous scholar, was the first person to advocate literati painting, which originated in the period of Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern dynasties. Literati painting focused on the unity of poetry, literature and painting, as well as sentiment. This vital new branch greatly enriched the creativity and presentation of Chinese painting. It has not been surpassed by others, even though the artists of the Ming and Qing dynasties explored various techniques and concepts.

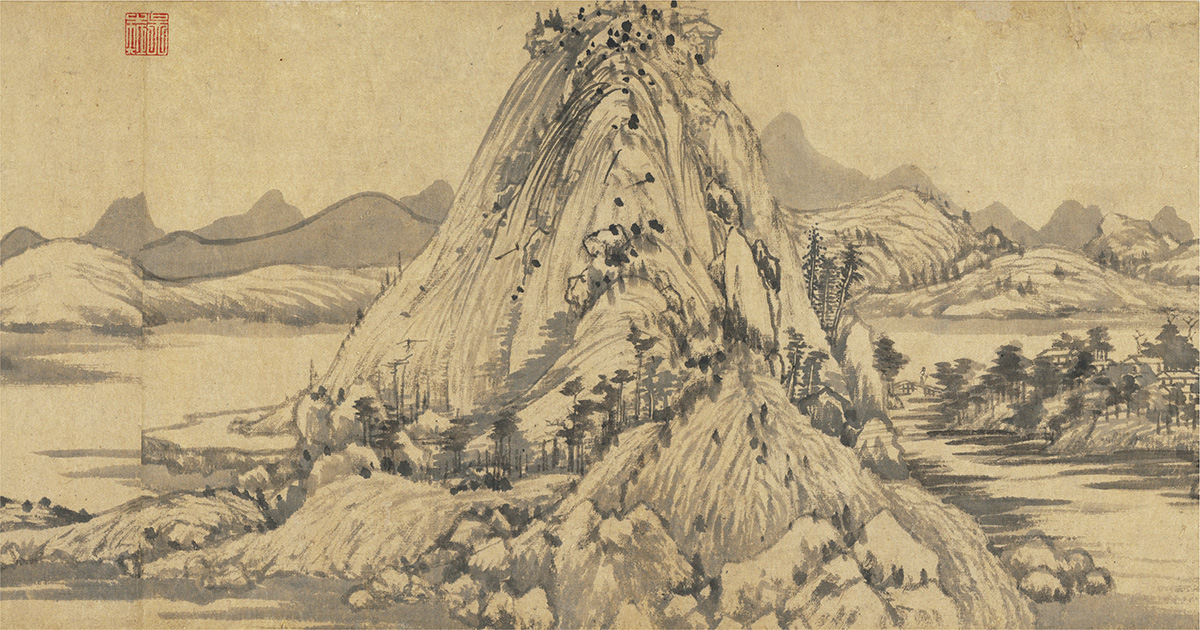

Fig. 9 Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (detail)

Yuan Dynasty

Huang Gongwang (1269–1354)

Ink on paper

Height 33 by length 636.9 centimeters

Palace Museum, Taibei

This painting depicts the landscape around the Fuchun River of Zhejiang Province in China. The mountains are painted intricately with rich variations of brush and ink techniques and the river is properly arranged. It fully illustrates the scenery from the river shore to the mountain peak. The use of ink is elegant with a full range of dark, light, dry and wet brush techniques to allow various expressions. It is one of the top 10 most famous Chinese paintings, as well as the most representative art piece by Huang Gongwang, showing his ideal landscape scene painted after seriously studying nature.

Fig. 10 A Lotus Flower Blossoming from the Water

Song Dynasty

Anonymous

Ink and color on silk

Height 23.8 by width 25 centimeters

Palace Museum, Beijing

A full-bloom pink lotus flower occupies the entire painting. The composition and color arrangement make the lotus flower very eye-catching against the green lotus leaves, fully depicting its noble character: “Growing out of the dirt and yet remaining pure; being cleansed by the water and yet not bewitched.”

No outlines can be found on the lotus petals, and this promotes their soft and smooth nature. The shape, orientation, shade and lighting of each petal are neatly arranged; even the veins on the petals and the pollen on the stamens are illustrated in details. This proves that the artist had a high level of realistic painting skill.

Bird-and-flower painting has also gone through a lengthy evolution. In the period of Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern dynasties, flowers, birds, insects and animals were the most popular objects. Bird-and-flower painting became an independent genre in the Tang Dynasty, and the style reached its peak in the Song Dynasty as artists expanded their topics, advanced their skills and diversified their styles. In the Yuan Dynasty, the influence of literati painting helped make ink bird-and-flower the preeminent art form. Different schools and styles flourished in the Ming Dynasty, and artists developed innovative techniques in the Qing Dynasty.

The styles of Chinese painting can be classified into gongbi (meticulous style) and xieyi (freehand style).

Gongbi-style painting retains the traditional realist style with meticulous technique (fig. 10). Line drawing is the backbone and emphasis of gongbi painting, which requires neat, delicate and rigorous skills, with the artist using the centered-tip stroke while painting. It is commonly painted on ripe silk or mature xuan paper. To make a perfect painting, first sketch, then finalize. Next smear alum solution onto the silk cloth or xuan paper. Use a fine, weasel-hair brush to outline the object and fill it with color. The ink and colors must be applied in several layers to create a unity of form and spirit.

Xieyi-style painting is freehand and emphasizes concepts, portraying a complicated object using a few strokes (fig. 11). It can be further broken down into great xieyi and slight xieyi styles. In this book, we will discuss more the slight xieyi style, which illustrates an object more realistically and with brighter colors.

Whether the theme is figure, landscape or bird-and-flower, Chinese painting is an art form for expressing concepts and ideas. These three objects summarize the three main concerns of the universe: Figure painting portrays the relationships among people in human society; landscape painting presents the relationship between the unity of humans and nature; bird-and-flower painting illustrates various creatures in nature and their harmonized relationships with humans. These three categories demonstrate a philosophical idea derived from art: The complete universe is formed by unifying these three ideas, and they bring out the best of each other. This represents the true meaning of art.

Chinese artists tend to focus on humans and their harmony with nature. When painting nature, they abandon objective perspective and actual form. Instead, they capture the spirit of nature and internal law to express their subjective feelings and traditional Chinese cultural and philosophical ideas. Not limiting yourself to realistic presentation is a way to express freedom in art.

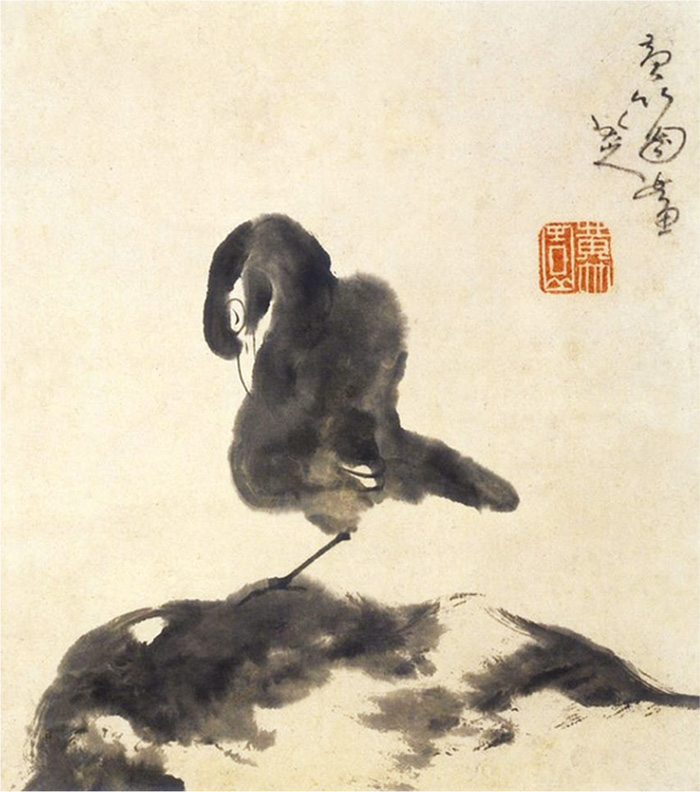

Fig. 11 The Book of An Wan: Bird and Rock

Qing Dynasty

Bada Shanren (Zhu Da) (c.1626–1705)

Ink on paper

Height 31.8 by width 27.9 centimeters

Sen-oku Hakuko Kan of Japan

Bada Shanren is famous for his unrestrained freehand ink wash painting, using simple technique to demonstrate the idea that less is more. The Book of An Wan consists of 22 paintings, his representative work produced in his later years. The main themes are flower, bird, landscape and calligraphy, which are presented with unique objects, in relaxed artistic conception, and with skillful use of ink and water.

This painting is the seventh piece of the book, and portrays a bird resting on a rock. The lowered head, protruded belly and cocked back make the body rich in variation. The bird seems like a secluded hermit, caring nothing about the world.