Chapter 12. Applying Psychological Principles in Design

The wealth of knowledge afforded to designers by behavioral and cognitive psychology research provides an invaluable foundation for creating human-centered user experiences. Much like an architect with an intimate knowledge of how people experience space will create better buildings, designers with an understanding of how humans behave will create better designs. The challenge becomes how to build that intimate knowledge and make it part of the design process. In this chapter, we’ll explore some ways designers can internalize and apply the psychological principles we’ve looked at in this book and then articulate them through design principles that relate back to the goals and priorities of their teams.

Building Awareness

Building awareness is perhaps the most obvious but effective way for designers to internalize and apply the psychological concepts covered in this book. The following are a few strategies I’ve seen implemented within teams to do this.

Visibility

The first and easiest way to internalize the principles discussed in this book is to make them visible in your working space. Since launching my Laws of UX project, I’ve received countless photos from teams that have printed out each of the posters available on the website and put them up on the walls for everyone to see (Figure 12-1). It makes me incredibly proud to see my work on office walls all around the world, but I also realize it serves a functional purpose: building awareness. By being constantly visible to the teams, these posters help to remind them of the various psychological principles that can help guide decisions during the design process. In addition to this, the posters serve as a reminder of the way humans perceive and process information. The result is a shared collective knowledge and vocabulary around these principles that’s cultivated within the organization. Ultimately, this leads to team members capable of articulating the principles and how they can be applied to the design work being produced.

Figure 12-1. Laws of UX posters helping to build awareness (credit: Xtian Miller of Vectorform [left], and Virginia Virduzzo of Rankia [right])

Show-and-Tell

Another method for building awareness within teams on any topic is the classic show-and-tell: the practice of showing something to an audience and telling them about it. Like many of you, I was first exposed to this activity in my early years through school, and it’s always been something I’ve enjoyed. Grade school teachers often use this activity as a way to teach students about public speaking, but it’s also a great format for team members to share knowledge and learnings amongst themselves.

The design teams I’ve been part of that have established a regular dedicated time for knowledge sharing have benefited from this practice in a number of ways. First, it’s an effective way to share information that could be useful to other team members. It’s a low-cost means of distributing information in a format that’s likely to be remembered. Everything from design techniques and new tools to usability test findings and project recaps—and yes, psychology principles—will be valuable to someone on the team. Additionally, show-and-tells are great for building speaking confidence in team members and giving people an opportunity to establish themselves as subject matter experts, and they indicate an overall dedication to and investment in continual learning on the part of the organization. It’s about creating a culture of dialogue and knowledge building within the team, which I’ve found means a lot to team members, myself included.

While simply building awareness might not firmly embed these principles into the design process of an entire team, it definitely can help influence design decisions. Next up, we’ll take a look at how these principles can be made instrumental to the design process within a team, and how to further embed them into decision making.

Design Principles

As design teams grow, the number of design decisions that must be made on a daily basis will increase proportionally. More often than not, this responsibility will land on design leadership, who must shoulder it alongside their numerous other responsibilities. Once the team reaches a certain threshold and the volume of design decisions to be made exceeds what it’s possible for leadership to manage, the output of the team will slow down and become blocked. Another scenario could be that design decisions are made by individual team members without approval, and therefore without the assurance that they meet the standard of quality, objectives, or overall design vision of the team. In other words, design gatekeepers can become an obstacle to consistency and scalability. To add to this problem, the priorities and values of the team can become less clear, resulting in individual team members defining what good design looks like to them, not necessarily to the overall team. I’ve seen this happen firsthand, and as you might imagine, it’s problematic, because the definition of “good design” within the team becomes a moving target. The result is less consistent output from the team overall. The output of the team will inevitably suffer as a result of inconsistency and lack of a clear vision.

One of the most effective ways we can ensure consistent decision making within the design process is by establishing design principles: a set of guidelines that represent the priorities and goals of a design team and serve as a foundation for reasoning for decision making. They help to frame how a team approaches problems and what it values. As a team grows and the amount of decisions to be made increases proportionally, design principles can serve as a North Star: guiding values that embody what good design looks like for the team. Gatekeepers are no longer a bottleneck, as the team has a shared understanding of what a successful design solution looks like in the context of these shared values and goals. Design decisions become quicker and more consistent, and the team has a common mindset and overall design vision. When done correctly, the ultimate impact this has on a team is profound and has the potential to influence the entire organization.

Next, we’ll take a look at how you can begin to define your team’s guiding values and resulting design principles in order to ultimately connect these to foundational psychological principles.

Defining Your Principles

There are a variety of methods you can use to define a set of design principles that reflect your team’s goals and priorities. While a comprehensive look at the various ways to enable team collaboration and orchestrate workshops is outside the scope of this book, it’s worth giving some context. The following is a common process for defining a team’s guiding design principles:

- 1. Identify the team

- Defining design principles is commonly done during a workshop or series of workshop activities, so the first step is to identify the team members who will participate. A common approach is to keep things open to anyone who wishes to contribute—especially those whose work will be directly affected by the principles. It may also be a good idea to open the process to design leadership and stakeholders outside of the immediate team, as they will bring a different perspective that’s also valuable. The more people you can get involved, the easier it will be to ensure widespread adoption.

- 2. Align and define

- Once the team is identified, it’s time to carve out some time and kick things off by first aligning on success criteria. This means not only creating a shared understanding of design principles and the purpose they serve, but also defining the goals of the exercise—for example, defining what criteria each design principle must meet to be valuable for the team.

- 3. Diverge

- The next step is commonly centered around idea generation. Each team member is asked to brainstorm as many design principles as they can for a defined amount of time (say, 10–15 minutes), writing each idea on a separate sticky note. By the end of this exercise, each participant should have a stack of ideas.

- 4. Converge

- After divergence comes convergence, so the next step is to bring all those ideas together and identify themes. Participants are usually asked during this phase to share their ideas with the group and to organize those ideas according to themes that surface during the exercise, with the help of a facilitator. After all the participants have shared their ideas, they are asked to vote on the themes they feel are the most appropriate for the team and the organization. A common exercise for this is “dot voting,” where each person receives a finite number of adhesive dots (usually 5–10) that they use to vote. The themes they choose to vote on are entirely up to them, and they can even use multiple dots on a single theme if they feel particularly strongly about it.

- 5. Refine and apply

- The next step will vary per team, but it’s common to first undergo a refinement stage and then identify how the principles can be applied. Themes should be consolidated where possible and then articulated clearly. Next, it’s a good idea to identify where and how these principles can be applied within the team and the organization as a whole.

- 6. Circulate and advocate

- The final step is to share the principles and advocate for their adoption. Circulation can come in many forms: posters, desktop wallpapers, notebooks, and shared team documentation are all common mediums. The goal here is to make them readily accessible and visible to all members of the design team. Additionally, it’s critical that team members who participated in the workshop advocate for these principles both within and outside the team.

Best Practices

Design principles are valuable only when they can effectively provide guidance and frame decision making. The following are a few best practices to help ensure the design principles your team adopts are useful:

- Good design principles aren’t truisms

- Good design principles are direct, clear, and actionable, not bland and obvious. Truisms can’t help with decision making because they are too vague and lack a clear stance (for example, “design should be intuitive”).

- Good design principles solve real questions

- You’ll want to make sure the principles you define can clearly resolve real questions and drive design decisions. Be careful, though—you don’t want them to become too scenario-specific.

- Good design principles are opinionated

- The principles you define should have a focus and a sense of prioritization, which will push the team in the right direction when needed and drive them to say no when necessary.

- Good design principles are memorable

- Design principles that are hard to remember are less likely to be used. They should feel relevant to the needs and ambitions of the team and the organization as a whole.

Connecting Principles to Laws

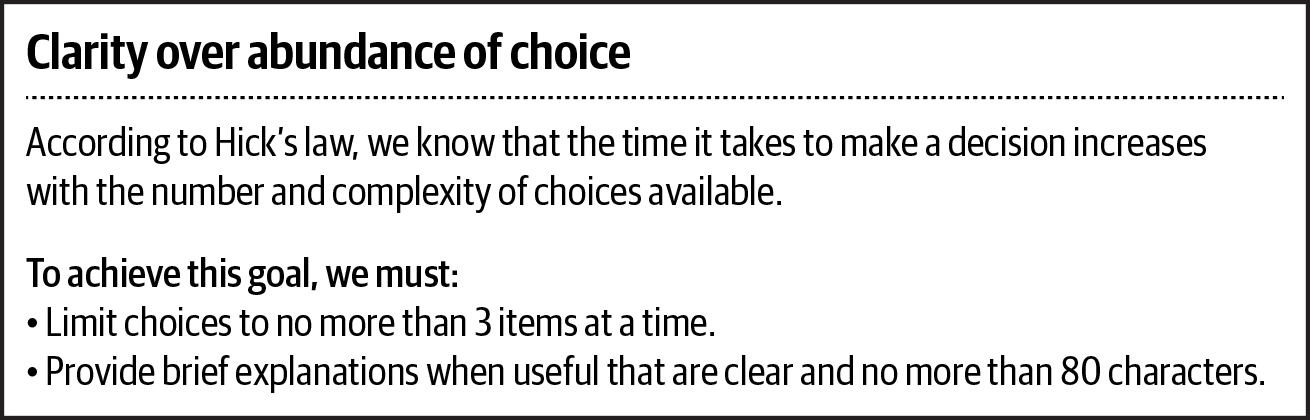

Once your team has established a set of design principles, consider each of them in light of the psychological principles discussed in this book. By doing this, you can make the connection between what the design principle is seeking to accomplish and the psychological reasoning behind it. Suppose, for example, that your design principle is “clarity over abundance of choice.” This principle is quite useful because it not only prioritizes clarity but also establishes the trade-off (loss of abundant choice). To align this principle with a law, we must identify the one that most relates to this goal of providing clarity. Hick’s law (Chapter 3), which states that “the time it takes to make a decision increases with the number and complexity of choices available,” seems to be a good match in this case.

Once the connection is made between a design principle and the appropriate psychological law, the next step is to establish a rule for team members to follow in the context of the product or service. Rules help to provide constraints that guide design decisions in a more prescriptive way. Continuing with the previous example, we’ve identified Hick’s law as the appropriate law to connect to our design principle of “clarity over abundance of choice,” and we can now deduce rules that are appropriate for that design principle. For example, one rule that aligns with this law would be to “limit choices to no more than 3 items at a time.” Another rule that could be appropriate is to “provide brief explanations when useful that are clear and no more than 80 characters.” These are simple examples that are meant to illustrate the point—the ones you’d define would be appropriate for your project or organization.

We now have a clear framework (Figure 12-2) that consists of a goal (design principle) and an observation (law) and establishes guidelines (rules) that designers can follow to meet this goal. You can repeat this process for each of the design principles that your team has agreed upon to create a comprehensive design framework.

Figure 12-2. An example design principle, observation, and rules

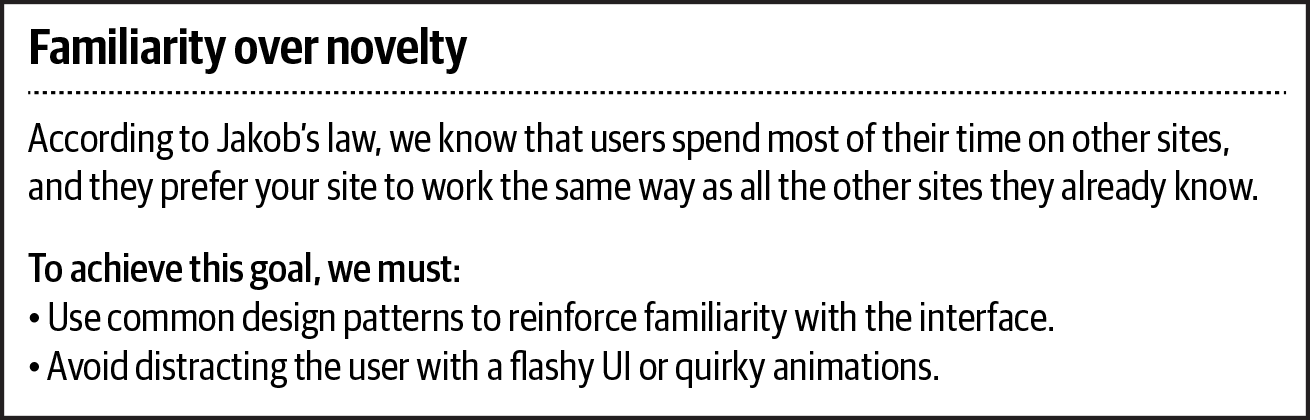

Let’s take a look at another example: “familiarity over novelty.” This passes the criteria we’ve set for what a good design principle should be, so it’s time to identify the law that most relates to this goal of providing familiarity. Jakob’s law (Chapter 1), which states that “users spend most of their time on other sites, and they prefer your site to work the same way as all the other sites they already know,” is a pretty good match. The next step is to establish rules for team members to follow in order to provide further guidance and ensure the principle is actionable. Familiarity is supported by the use of common design patterns, so we’ll start by establishing that we should “use common design patterns to reinforce familiarity with the interface.” Next, we can further recommend that designers “avoid distracting the user with a flashy UI or quirky animations.” Once again, we now have a clear framework (Figure 12-3) that consists of a goal and an observation and establishes rules that designers can follow to meet this goal.

Figure 12-3. Another example design principle, observation, and rules

Conclusion

The most effective way to leverage psychology in the design process is to embed it into everyday decision making. In this chapter, we explored a few ways designers can internalize and apply the psychological principles we’ve looked at in this book and then articulate them through design principles that relate back to their team’s goals and priorities. We started by looking at how you can build awareness through making these principles visible in your working space. Next, we looked at a simple method for cultivating a culture of dialogue and knowledge building within the team through the classic show-and-tell format. Last, we explored the value and benefits of design principles, how to establish design principles, and how to make the connection between what each principle is seeking to accomplish and the psychological reasoning behind it. You can do this by establishing the goal, the psychological observation that supports this goal, and finally the means by which it will be applied through design. Once this process is complete, your team will have a clear road map that not only lays out its shared values through a set of clear design guidelines but also provides both the psychological validation to support these guidelines and an agreed-upon set of rules that help ensure the team can consistently meet them.