THE INSECTICIDE DDT WAS CONSIDERED A WONDER CHEMical when first introduced to the world, and as well it should have been, given the early successes associated with its use.

It was effective, inexpensive, and had many applications.

These very properties led to its widespread use, and, it could be argued, its demise. When it was employed in the effort to save America’s elm trees, it came face-to-face with a public that might not have otherwise given it much thought. A generation of city dwellers got to see some of DDT’s darker sides.

A member of the chlorinated hydrocarbon family, DDT was first synthesized in 1874. It wasn’t until 1939, though, that a team of investigators working for Geigy Chemical Company of Switzerland would identify its powerful pesticide punch. The team’s leader, Paul Muller, won the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery.

Little wonder. DDT was credited with saving tens of thousands of human lives. It was first put to use in World War II and helped protect thousands of US military personnel who would otherwise have been exposed to malaria, typhus, and other insect-borne diseases. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, wisely shortened to DDT, quickly earned its stripes.

Muller was saluted in the Nobel presentation speech by Professor G. Fischer, member of the Staff of Professors of the Royal Caroline Institute:

“The story of DDT illustrates the often wondrous ways of science when a major discovery has been made. A scientist, working with flies and Colorado beetles discovers a substance that proves itself effective in the battle against the most serious diseases in the world. Many there are who will say he was lucky, and so he was. Without a reasonable slice of luck hardly any discoveries whatever would be made. But the results are not simply based on luck. The discovery of DDT was made in the course of industrious and certainly sometimes monotonous labour; the real scientist is he who possesses the capacity to understand, interpret and evaluate the meaning of what at first sight may seem to be an unimportant discovery.”1

Communities seeking to control Dutch elm disease sometimes resorted to spraying DDT by helicopter. Citizens in many communities were alarmed when the insecticide led to songbird deaths due to acute exposure. WHi Image ID 72978

A familiar sight on many American streets in the 1960s: the spraying of elm trees with DDT in an effort to halt the spread of Dutch elm disease. Spraying often took place at night, and citizens were warned to go inside as trucks pulled misting machines that launched an emulsion containing DDT to the tops of trees. WHi Image ID 73014

The same might be said of the ecological scientists who years later uncovered the mystery of how DDT was seriously impacting wildlife.

Fischer’s reference to the flies failed to mention another fact that would ultimately affect DDT’s future: at least one species of house fly had already become resistant to the compound. Other insect species would develop similar resistance, including, DDT foes later argued, the mosquitoes that spread malaria.

But any negatives were far outweighed by positives as humans rushed into the second half of the twentieth century. DDT and other related compounds—chlorodane, toxaphene, aldrin, and dieldrin—were the dominant family of insecticides used after World War II.2 DDT quickly earned favor as a preferred and effective agent for chemical control of pests on agricultural, forest, and city landscapes in the United States, Europe, and other developed regions.

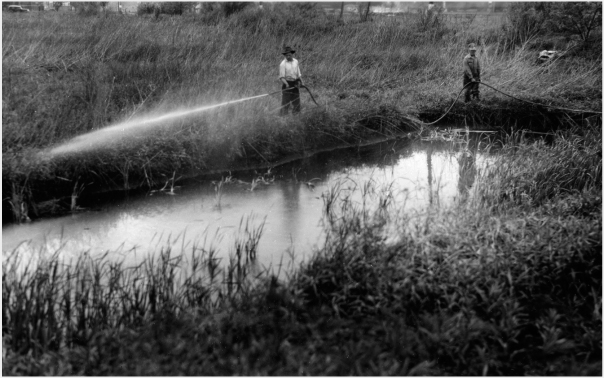

To combat mosquitoes, DDT was often sprayed in places where water gathered. The persistent pesticide is toxic to a wide range of living organisms, including many species of fish. DDT, through its metabolite, DDE, causes eggshell thinning in a number of birds of prey and certain other bird species. Some species, such as the bald eagle and peregrine falcon, experienced drastic population declines during years of heavy DDT use. WHi Image ID 60301

Children of the 1960s in eastern US cities—where DDT was aimed at the Dutch elm beetle—recall riding their bikes through the mist behind DDT foggers. They did not die, although countless songbirds around them did. The apparently negligible impact on humans served as one of the major arguments for widespread use of the pesticide: direct human exposure at high levels did not seem to produce serious symptoms. Even Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring failed to make a strong case that DDT and other chemicals were harmful to humans.

Thomas Dunlap, author of DDT, Scientists, Citizens and Public Policy, captured the cultural and scientific realities that helped usher in the era of DDT and other chemicals when he wrote, “The failure of other methods to meet public demands for ways to stop insects without long, expensive research, changes in farming practice or long-term planning paved the way for chemicals. The triumph of chemical insecticides was due not just to the visible results they gave, but to their acceptance by a public and a farming community that valued, above all else, convenience, simplicity and immediate applicability.”3

DDT was introduced in 1942, and it drew raves from those looking for better insecticides. Dunlap’s book notes that one economic entomologist who tested DDT on potatoes described the results years later, saying DDT was “a miraculous pesticide.”4

With the rise of DDT came the corresponding rise of a new breed of scientist: the economic entomologist, whose job it was to save humankind and wrestle control of the earth—including the elm-lined streets of the eastern United States—from insects. The entomology department in the College of Agriculture at the University of Wisconsin in Madison flourished in this post–World War II environment.

Public debates about the use of chemicals in food production took place not long after DDT was introduced. Some scientists had warned of DDT’s chronic impacts almost immediately, but these discussions eluded average Americans.

Then came Carson’s seminal book, which paralleled the growing use of DDT in populated settings. Soon, another new breed of experts, ecological scientists, were talking about widespread impacts of insecticides on the environment. They established with growing scientific certainty that, in addition to acute toxicity to many species—notably songbirds—DDT packed a heavier punch in other bird species higher on the food chain through chronic exposure. DDT was mobile and persistent, and it accumulated in nontarget species. Ecological scientists began to establish that in sufficient levels of accumulation, DDT’s metabolites caused reproductive problems in a number of species. This led to a quiet but deadly decline in scores of species, a heretofore unheard of phenomenon and one that escaped the immediate attention of wildlife biologists because such species, including raptors, are long-lived, and their population declines were not initially obvious because live birds were still seen.

The chemical industry, backed by its own stable of respected and knowledgeable scientists, fought back with vigor. They had the financial resources to do so, and they used them.

But science is only part of the DDT story. Among the earliest to see that something was off-kilter were bird-watchers and gardeners in cities and genteel suburbs who took note of population declines in songbirds. If they had a hard time connecting with scientists on the issue of DDT use, they had less luck with municipal officials who were following USDA and state agricultural agency advice about how to handle insect pests and struggling to save the monoculture urban elm forests. Saving elm trees was also important to local governmental budgets: removing and properly disposing of dead trees was costly and time-consuming. Urban foresters were pressed into using DDT as a cost-effective if not entirely successful means to control the spread of Dutch elm disease.

But backyard naturalists persisted. Aldo Leopold had reminded the world that “to keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”5 Bird-watchers and gardeners like Lorrie Otto were among the first to notice that we were losing some of the parts. They would lead efforts to literally put DDT on trial in the public arena. It can be said that it all started with the robin.