IT IS NOT MUCH OF AN EXAGGERATION TO ATTACH THE ADVENT of the modern environmental movement to the time when American robins started twitching and dying in citified gardens, yards, and boulevards across the eastern United States.

It is also fitting that some of the earliest modern-day environmental skirmishes should be in Wisconsin, where schoolchildren voted Turdus migratorius—the American robin—the state bird in 1927.1

Acute DDT exposure, which dropped robins and other songbirds on lawns, wasn’t the ultimate reason for the pesticide’s demise, but it served as the first warning of its toxicity as birds began perishing in great numbers.

It was an elderly woman who first told Charles Wurster, who was at the time a biology postgraduate fellow at Dartmouth, in Hanover, New Hampshire, that DDT was killing birds. Like so many other towns across the eastern United States, Hanover was engaged in a determined if futile effort to control Dutch elm disease with DDT.2 “Her name was Betty Sherrard,” Wurster recalled. “She was certainly interested in birds.” In 1960, Sherrard invited Wurster and others to a party at her home, intending to share more than nosh. “She passed around this petition to the town fathers in Hanover, asking them not to spray because it killed birds,” Wurster said. “Well, the petition went to the town managers, and they said they were real careful, and their spray didn’t kill birds, and it was some kind of nerve disease that killed the birds.”3

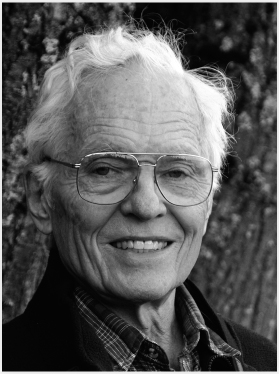

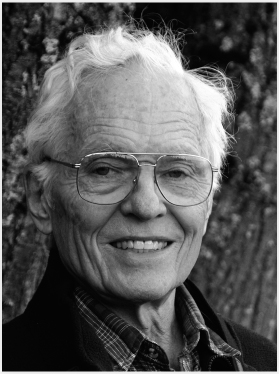

Charles Wurster was a scientist and cofounder of the Environmental Defense Fund. He and EDF played key roles in Wisconsin’s DDT hearing. Courtesy of Stony Brook University

That party would change Wurster’s life. He and some colleagues undertook what he called “a little study and found out what was happening.” Their work eventually led the town to halt the spraying. Betty Sherrard the citizen activist had found her man. In 1967, Wurster, who had moved on to the State University of New York at Stony Brook, helped found the Environmental Defense Fund. It was an organization that wasn’t interested in pussyfooting around on matters that concerned the environment. Early in its existence, the EDF believed the best way to achieve victories for the environment was in legal settings. Similar to many early environmental organizations, the EDF moderated its positions over time.

Wurster had learned something else when he began to poke into the mystery. For years, citizens had been taking note of bird deaths in other populated areas where elm trees were sprayed with DDT, primarily in the East and Midwest. It was especially true in the Midwest, where the connection had been noted much earlier than in Hanover, he discovered.

An early Wisconsin environmental activist, Dixie Larkin of Milwaukee, told the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology at its 1957 meeting in Green Lake that “the D.D.T. used to destroy the Dutch Elm Disease is killing many birds.”4 At the meeting, Walter Scott, who served in the position of “custodian” for the group, said he felt the right way to treat the disease without killing birds would be found. Scott would go on to play a major role in efforts to ban DDT. A longtime staff member of the Wisconsin Conservation Department, which evolved into the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources in 1968, Scott flooded people like Lorrie Otto with new research, insider tips that helped the citizens’ cause, and leads on where to look for more information, all while serving as assistant to the director of the department and in other positions. He was also one of the founders of the Citizens Natural Resources Association.

Indeed, the first alarms were being sounded across the eastern United States and in midwestern cities like Milwaukee and its suburbs, prompting letters to newspaper editors and this 1957 communication from Marie Thompson of Milwaukee, president of the Animal Protective League, to John Beale, chief forester of the Wisconsin Conservation Department: “Dear Mr. Beale: We implore you to stop the use of all DDT spraying—which is a complete violation of all of our laws and treaties re: migratory birds, game birds and wild animals taken out of season. The death toll is shocking & we all have the right to protect our birds and wildlife.”5

Complaint upon complaint piled up in urban areas where DDT was used. The complaints, though, were mostly anecdotal, and some were easily dismissed. But local officials were under pressure: other citizens were imploring them to save the beloved cathedral elms that arched over their streets, cooling summer days and cutting winter winds. In the face of protests about bird deaths, many city dwellers agreed with the village of Bayside official who asked the now infamous question of Lorrie Otto, “What do you want, Mrs. Otto, birds or trees?”6

The question itself was not completely out of line. Even though wildlife researchers including Clarence Cottam and Elmer Higgins with the US Department of the Interior had warned as early as 1946—the year widespread use of DDT began in the country—of the effects DDT had on fish and other wildlife,7 other respected scientists argued that the benefits of DDT outweighed any potential risks. Some predicted dire consequences for US agricultural crops and forests if DDT was banned. The work of Cottam and Higgins anticipated the coming push and pull among agencies such as the Department of the Interior, which had managing wildlife populations as part of its mission, and the Department of Agriculture, which was focused on agricultural production and feeding the public. With such divergent missions, it should be of little wonder the two departments did not see eye to eye. The same tension was obvious in the states—Wisconsin not the least of them—where conservation and agriculture departments often held conflicting views and offered contradictory advice to their stakeholders.

Dutch elm disease struck hard and fast once it arrived. In this photo, trees on one side of a street in Shorewood Hills, Wisconsin, are dead. Those on the other side of the street would suffer a similar fate despite efforts to control the disease with DDT and other compounds. US Forest Service

For his part, Cottam, a long-serving government biologist unafraid of a tussle,8 had warned of looming danger in 1945. Excessive use of DDT, he said, could kill an array of species, from birds and fish to turtles and frogs. DDT “will kill a lot of things we don’t want killed,” Cottam warned. “It kills beneficial insects as well as obnoxious insects. Therefore, it should be used with understanding, intelligence and caution. If used in excess, it will be like scalping to cure dandruff.”9

Cottam’s choice of colorful language underscored the fact that scientists were split on the topic, often by discipline. Even as Joseph Hickey’s work at the University of Wisconsin in Madison became a crucial link to understanding the full impacts of DDT, a prominent scientist and administrator at the school took a different position. Dr. Ira Baldwin, a plant bacteriologist who spearheaded US chemical warfare research in World War II, would write a critical review of Silent Spring in Science magazine in 1962. Faculty at the university would continue to be divided—sometimes angrily so—as the DDT story unfolded. At times, it seemed as though the message on a plaque at the entrance of Bascom Hall, the main administrative building at the university, might be compromised: “Whatever may be the limitations which inhibit inquiry elsewhere, we believe that the great state university of Wisconsin should forever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”

Meanwhile, citizen complaints continued. The early tales of bird deaths and citizen concerns are eerily similar. They often involve a disgruntled citizen dropping off a batch of dead birds at a local governmental office. Wisconsin author Jerry Apps was a county extension agent in Green Bay in the early 1960s and a member of the local National Audubon Society chapter (Northeastern Wisconsin Audubon Society). A fellow club member approached him in his office one day with a basket of dead birds.10 She asked why the Extension Service offered instructions on the use of DDT to control lawn and garden pests when it killed birds so readily. Apps recalled not having a ready answer.

In the upscale Milwaukee suburb of Bayside, Lorrie Otto was springing into action. She had been pestering people with her environmental activism for years by the time she dropped off a load of twenty-eight dead robins at the Bayside village offices. A housewife with a penchant for gardening and native plants, Otto became dogged in her efforts to put an end to DDT spraying. She was frequently frustrated with the response her work received and often ran out of patience with or didn’t trust bureaucrats going by the books, but she continued undeterred.

She was not, as it turns out, one to trifle with. She had already tangled with officials over efforts to save a twenty-acre wooded area along the Lake Michigan shore that was being eyed for a subdivision. As she edged toward action on DDT, she was encouraged by the likes of George Wallace, a Michigan State University zoologist who had conducted pioneering studies on DDT bird mortality in Michigan in the mid-1950s. In 1966, responding to a letter and other materials from Otto, Wallace wrote her: “I think you ‘gals’ have more influence on public opinion than you realize. Many a battle has been lost or won by pressure from the local citizens, especially women. People like me dig up the facts, by research, then publish the results in some obscure journal which nobody reads, except a few people who already know the story.”11

So the citizens’ uprising went from community to community, with people complaining about dying birds and municipal officials desperately trying to save the cathedral elms.

The uprising came in fits and spurts at first, mostly reported by “Audubon ladies”—Hickey’s reference to Illinois women who reported robin deaths in the journal of the Illinois Audubon Society12—who noticed the decline in bird numbers; by gardeners, who witnessed robins flopping about in fits and dying in their yards; and by children, who picked up dead birds on the tree-lined boulevards of their eastern and midwestern neighborhoods.

Hickey would later recount his own early introduction to the matter of DDT and birds. “It started when I went to a funeral in Kenilworth, Illinois, in June 1958,” he told author Thomas Dunlap. “There was a mulberry tree in front of the house. It was loaded with berries and there were no birds. I realized something was extraordinarily wrong, so I asked the local people ‘Where are the birds? Where are the robins?’ They said there were robins earlier in the spring but they all went north. When we got out of town and to a golf course in the next town, I saw robins.”13

Kenilworth, an affluent suburb, had a problem. Hickey knew something was wrong, but at that time he could not envision what the next decade-plus would produce. A careful scientist, he was loath to go too far in his assessment of the bird deaths until he had all his facts. And he had little or no idea about DDT’s other face: the chronic, sublethal dosage that would wreak havoc on birds of prey and other species. He returned to his work back in Madison, where the university was spraying DDT in an effort to save its iconic elms. The next decade would produce a remarkable unraveling of a scientific mystery, and he would be in the center of it.

As Hickey carefully edged closer to action in the 1960s, Otto was carrying on a sort of one-woman campaign in her suburb and throughout the Milwaukee area. The record indicates that she didn’t hook up with the CNRA in these early efforts. The trail of correspondence from her files shows she reached out first to Wallace and Wurster, who in turn linked her back to Hickey and the CNRA folks—some of them her neighbors.

Wurster, already convinced of DDT’s danger and less cautious than Hickey, was ready for action. In response to a letter and other materials from Otto in 1965, he replied: “This whole pesticide business is a real problem, and the forces at work are hard to beat. If the city sprays your trees without your permission, can’t you sue them? Gather the garden clubs and bird clubs together and hit the city with 100 lawsuits. You can produce buckets of evidence to prove that DDT is killing desirable wildlife. The biggest problem is to inform people of the facts.”14

In the same letter, Wurster steers Otto to Wallace and Hickey.

So it appears that the 1965 exchange between two activists—one a scientist, the other a housewife—played a crucial role in the coming together of a group of Wisconsin and New York environmental activists. The story unfolded rapidly in the next few years, though time seemed to be moving slowly for those, like Otto, who wanted immediate action. Joseph Hickey was not among them. He had more work to do.