ONE DAY IN 1964, LORRIE OTTO COLLECTED TWENTY-EIGHT dead robins and dumped them on the desk of the Bayside village manager.

Upscale Bayside, a Milwaukee suburb, seemed an unlikely place to nurture an environmental leader who would step to the forefront of the DDT battles in Wisconsin. But some earlier skirmishes prepared her, including protecting a natural gem in the suburbs from development and defending her right to natural landscaping in her yard.

These early confrontations, stretching back to the 1950s, steeled the woman who referred to herself in her younger days as a shy farm girl. The shy farm girl would go on to help found the natural landscaping movement in the United States. She would engage in a number of environmental causes, but none took so much of her time and energy as the DDT battle.

Several names emerge in the ranks of Wisconsin citizen activists who pushed for a ban on DDT. Foremost among them are Otto and Joseph Hickey. It was still pretty much a man’s world in the 1950s and 1960s, but women played key roles in the DDT battle, perhaps influenced by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. In Wisconsin, women took the lead against DDT in several important areas. In addition to Otto, there was the young reporter at the Capital Times newspaper, Whitney Gould, who covered the hearing from gavel to gavel. Two of the top four Citizens Natural Resources Association officers at the time of the DNR hearing were women: Carla Kruse and Bertha Pearson. And arguably the most crucial testimony on behalf of the environmentalists’ cause would come from Lucille Stickel, a scientist with the US Department of the Interior’s Fish and Wildlife Service.

Most of the others on both sides of the DDT fray were men, but this handful of women made a difference. Their growing involvement was a sign of things to come.

Otto and her husband, Owen, moved to the village of Bayside in 1952. A few feet from the rear windows of their home was a mini-wilderness called Fairy Chasm, a ravine cut by Fish Creek and kept moist by chilly fogs off Lake Michigan. It was rich in plant and animal life. The Otto home was one of eighty residences developed by the Fish Creek Park Company. In 1960, road repairs were needed, but the corporation bylaws forbade assessments. Directors had two choices: ask the residents for donations or subdivide part of Fairy Chasm into nineteen lots to be sold to cover the cost of road improvements. “I knew it was wrong to destroy the woods, but I needed the language,” she told a reporter years later.1 So she went in search of the words to make her point. Otto asked her local bookstore operator for every book in the store about identifying flowers, shrubs, and trees. She also asked for books on the environment. One was Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac.

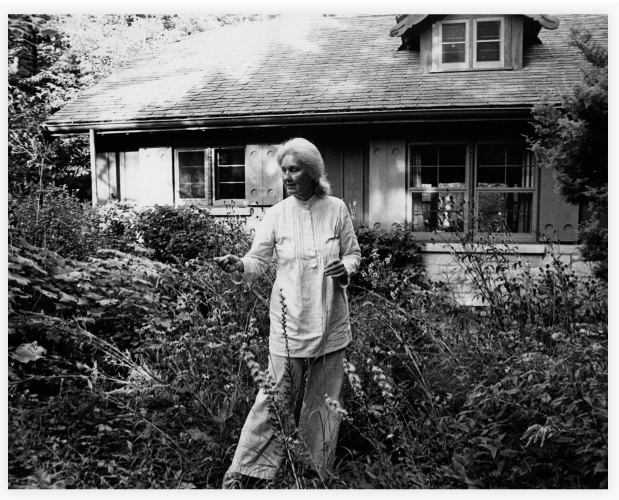

Lorrie Otto, shown here outside her Bayside, Wisconsin, home, was a key citizen activist in efforts to ban DDT in the state. Otto was also known nationally for leading the natural landscaping movement. WHi Image ID 100397

She also sought out Alvin Throne, a professor of biology at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. He had studied the rare plants of Fairy Chasm in the 1920s, and he bristled at the thought of their loss. Throne joined the cause. They sought out a Milwaukee Journal reporter, and the story ended up on page one. Other media coverage followed, and when it came time to vote, residents opposed subdividing the ravine by thirty-eight to thirty-four. The ravine was saved, and Otto learned an early lesson in environmental activism. The Nature Conservancy bought the property in 1970, making it one of the organization’s first Wisconsin holdings. Otto, an early TNC board member, was behind the transfer.

Otto’s “weed wars” with the village of Bayside were a good lesson in activism, too, even if she was pretty much alone in that skirmish. In the mid-1950s, she clashed with the village over her landscaping preferences. An early adapter of native plantings, she turned her suburban yard into a rich pastiche bursting with color and variety—a thorough departure from the well-manicured lawns of her neighbors.

Some of those neighbors and village officials saw weeds, not the diverse landscape Otto had created, and one day when she was away, the village mowed down her plants. There was a village weed law, after all. Otto was incensed. She demanded that village officials attend a guided tour of her yard. Using the incident as a teachable moment, she described for them each plant that had been mowed down. They conceded she had a point and reached a settlement with her. The natural landscaping movement took a giant step forward that day. Otto began to spread the word about natural landscaping. After hearing an Otto lecture in 1977, a group of nine women began meeting monthly to share information about natural landscaping. They called themselves the Wild Ones. Otto became their philosophical compass. The organization has chapters throughout North America today.

Lorrie Otto’s early life provided few hints that she would become a gutsy citizen activist and environmental leader. Born Mary Stoeber in 1919, she grew up on a Dane County, Wisconsin, dairy farm. By her own accounts, she was “terribly shy.”2 The family was from stoic religious stock. “We were Presbyterians, and it was a sin to be proud,” she said.

Still, nature was already tugging at her. The oldest of three daughters, she acquired her love of the land on that farm as she tagged along with her father. “I sort of became the son,” she recalled. “I was just his shadow. Loved every minute of it. My dad had such a feeling for the soil.”3

As a young single woman she began spreading her wings. She saw an ad for the Women Airforce Service Pilots while attending the University of Wisconsin in Madison during World War II and signed up. She was a WASP trainee in Texas near the close of the war, although the program ended before she could claim the official status of WASP pilot.

Stoeber had earlier met her husband-to-be, Owen Otto, in a high school play. They began dating at the University of Wisconsin. He emerged with a degree in medicine; she earned an undergraduate degree in related arts, a major that covered a range of artistic disciplines. They were married in 1944, and it was then she became Lorrie Otto—a sister-in-law already had the name Mary Otto, so Lorrie chose a variation of her middle name, Lorraine.

In 1950, Owen Otto was named medical director at Rogers Memorial Hospital, a psychiatric facility in Waukesha County. Two years later, they moved to Bayside with their two young children, Patricia and George.

Owen struggled with financial challenges at the hospital, and Lorrie raised the children. But seemingly unconnected events were already unfolding, and they would converge a decade later as Milwaukee’s seemingly happy days of the 1950s yielded to an altogether different decade.

A few years before the Ottos settled into their suburban home, Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac had been published, to little fanfare. Leopold’s first and only hire at the University of Wisconsin, Joseph Hickey, helped organize the manuscript and prepare it for publication. Leopold had died fighting a brush fire on a neighbor’s property near the family shack in 1948, barely a stone’s throw from the Wisconsin River and where he penned many of his essays. Hickey, hired by Leopold just a few months earlier, took over as chair of the Department of Wildlife Management, a small program within the College of Agriculture. It was Leopold’s baby, and one of the first in the nation. Hickey, already an ornithologist of international repute, was ready to settle into a career of teaching and research. He didn’t yet know Lorrie Otto.

The same year Owen Otto took the position at Rogers Memorial Hospital, the CNRA was forming, ignited by the controversy over tree cutting for a highway project. Early members of the CNRA whose lives would soon touch Lorrie Otto’s were already nearby, including Fred Ott, who would play a key role raising funds for the DDT battles, and Owen Gromme, who was on the staff of the Milwaukee Public Museum and a still-undiscovered wildlife artist. She couldn’t know it then, but Lorrie Otto would in a few years be working closely with these folks.

Otto was a relative latecomer to the CNRA, her name showing up as a new member—Mrs. Owen Otto—in 1968, the same year the Wisconsin administrative hearing over whether DDT was a water pollutant began. But she had been fighting the village of Bayside and other Milwaukee communities over DDT spraying for Dutch elm disease for several years, as evidenced by her trips to the village offices with the dead robins she had kept in her refrigerator. It was during one of those visits that she was asked the “birds or trees” question by the Bayside village manager. The village had begun helicopter spraying its elms.

It was a tough question, and one that municipal officials were likely asking themselves across much of the East and Midwest in their costly battle to save the elms. With elms dying at an alarming pace, there was pressure to save the trees and do so as cheaply as possible. DDT was less costly than other chemical treatments and considered more effective.

Otto knew there was something wrong when robins and other songbirds twitched, flopped about, and died on suburban lawns. She resolved to end or curtail the spraying. Her Milwaukee-area skirmishes were training for later battles that would mark the early stages of citizen environmental activism in the United States. Her correspondence from that period reflects a growing confidence, if a still-developing understanding of the constraints on people who worked in government. She was dedicated, determined, and impatient.4

Latecomer though she was to the CNRA, when Otto did get involved, she almost instantly became a big player.

Otto began her own personal crusade against DDT in the mid-1960s. She joined the Wisconsin chapter of the Nature Conservancy and got to know Hickey, who had already accumulated piles of research on the effects of DDT. On Hickey’s advice, Otto initiated contact with Charles Wurster, an Environmental Defense Fund founder and a young biologist/biochemist from the State University of New York at Stony Brook. In a 1965 letter responding to her call for help, Wurster reminded Otto that it was hardly fresh news that DDT was causing bird deaths, and he outlined courses of action that citizens might take. “It is simply a matter of fact that when DDT is used in the quantities customarily employed for Dutch elm disease, birds will be killed—lots of them,” he wrote. “This has been known for years, long before our reports, long before Silent Spring. The argument, then, is simply between those who know the facts, and those who don’t.”5

By this time, Wurster had published the findings of his research into bird deaths in the town of Hanover, New Hampshire, where he had been a student and faculty member at Dartmouth University, in the prestigious peer-reviewed publications Science and Ecology. The Science article, copublished with his wife at the time, Doris, and Walter N. Strickland, of the Department of Pathology at Dartmouth Medical School, concluded, “From the number of dead birds found, the many birds observed with tremors, chemical analyses of these birds, and a population decline among certain species, we conclude that DDT caused severe mortality of resident and migrant birds in Hanover during the spring of 1963.”6

Otto’s recollections of the mid- to late 1960s show she was gaining key allies in addition to Hickey and Wurster. She also got to know Walter Scott, who asked her to conduct a survey of DDT use in Milwaukee-area municipalities for possible use by the Wisconsin Conservation Department. She did so, in great detail, her findings carefully recorded by hand on several sheets of paper. Along the way, Otto also collected anecdotal information from people of a variety of backgrounds. Don Johnson, an outdoors reporter at the Milwaukee Sentinel, became a confidante.

Armed with this new information, Otto went back to the Bayside Village Board to argue again for a halt to spraying. “The only recollection I have of that evening is of a man slamming his fist on a table and shouting, ‘Young lady, keep your mouth shut or this will reverberate all the way to the halls of Congress,’” she recalled years later, wryly observing that the man was ultimately right.7

By 1968, with the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture sticking to its guns on the continued use of DDT for Dutch elm disease spraying amid growing citizen discontent, Otto and Hickey became determined to seek the help of the new outfit, the EDF. They headed for New York and a weekend meeting with Wurster at the EDF headquarters on Long Island.

With curly locks and a firm jaw, the forty-year-old scientist activist cut a dashing figure that didn’t go unnoticed by Otto. In a letter to a friend a few days later, she confided, “Charlie stole my heart. One doesn’t know whether to love him as a man or as a son. I plan to introduce my daughter to him.”8 At their first meeting on August 24, 1968, Wurster told Otto and Hickey it was time to act. “We have all the marbles,” he said. “We just need to roll them out in front of a judge.”9 Research underscoring the dangers of DDT was piling up. By this time, Hickey and other researchers had confirmed DDT concentrations in the Lake Michigan ecosystem: everything from chubs to gulls had concentrations of DDT or its metabolites. Three years earlier, Hickey had convened the conference in Madison on the fate of peregrine falcons. Scientists from several countries gathered to compare their research. Remarkably similar impacts on wildlife were widespread, and the research found one thing in common: the presence of DDT. Indeed, they had the marbles.

Otto was breathing rarified air. “That weekend was probably the most glorious of any in my life. In my memory, I see three Norwegians walking the beach on Long Island. Their ages spanned [20] years. Charlie Wurster was only 40. I was 50, and Joe Hickey was 60 years old,” she later recalled. “As we walked, the two men called out the amounts of DDT in the breasts of the birds flying over our heads, swimming in the ocean or running in the sand ahead of us.”10

The time for action had come. Little more than a month after the New York rendezvous, the CNRA was ready to move forward with its case. President Frederick Baumgartner wrote a letter “To all Organizations Interested in Conservation,” in which he made clear the group’s intent. “The CNRA has decided it is time for a test case of this question of water pollution [by DDT],” he wrote.11 Baumgartner outlined a dual strategy of pursuing a hearing on DDT and calling for various actions in the state Legislature. But there was one big problem: money, or lack of it.

As Hickey and Otto prepared to depart, Wurster let them know what they were up against financially. They needed a lawyer to admit the EDF’s attorney, Victor Yannacone, into the Wisconsin legal system and fifteen thousand dollars to pay airfare for EDF board members and witnesses from several states and, it would turn out, one foreign country. “My face fell so quickly it must have distressed Charlie,” Otto later recalled, “but he brushed it off with a wave of his hand and said, ‘Go to your group.’ Group? I didn’t have a group, unless it would be the PTA Art Committee, whose husbands in Bayside undoubtedly sprayed with DDT.”12

Otto knew CNRA had few resources, so she initially looked elsewhere for funds. She got six thousand dollars from a self-described “birding lady” in Oconomowoc. The Milwaukee Audubon Society provided six hundred dollars. The local Izaak Walton League had no money, but said it might be able to provide an attorney.

The CNRA would have to be the group. Though it lacked funds, the CNRA had expressed an early interest in the pesticide issue: the topic of its first conference, in the 1950s, was chemical sprays. Another conference, in 1958, produced a special report on pesticides.13

In Sauk County in 1964, CNRA members Harold and Carla Kruse initiated a petition drive on behalf of the group, seeking a halt to the chemical spraying of roadsides. CNRA records later noted it was the first citizen-organized effort in Wisconsin to stop chemical contamination of the environment. In 1966, the group cosponsored the Citizens Conference on Pesticides. The other cosponsor was the botany department at the University of Wisconsin. Hickey, then emerging as a citizen scientist who was growing more willing to stick out his neck, was one of five presenters. He spoke about DDT’s detrimental effect on birds and aquatic systems.

A February 26, 1967, statement from the CNRA president was clear about where the group stood:

“Are you about to become poisoned without your consent? This is the feeling many of us have at this time of the year, in spite of the hollow-sounding assurances that the poisons about to engulf us and our properties are well below our tolerance levels and those of the ‘desirable’ remnants of the natural environment we hope to keep around us. . . . The evidence against DDT seems as strong as that against the use of tobacco. The difference in effect is I abstain from tobacco by personal choice. I’m not allowed to make that same choice regarding DDT.”14

The CNRA president was Roy Gromme, and he and Lorrie Otto were soon to have an important conversation.

Just after Otto had called the owners of a honey farm who had sent ten dollars because they were concerned about its bees, Otto’s daughter, Tricia, came home from Nicolet High School. Hearing her mother’s story and accustomed to seeing dead birds in the freezer, she told her mother, “Why don’t you call my biology teacher, Mr. Gromme.”15

Otto later recalled, “I went directly to the phone. He asked me where we lived and said he’d be right over.” Roy Gromme would soon be leaving for India with USAID. But when they met that day, Gromme made Otto a promise. She recalled him telling her, “We will give you everything we have: all our money and mailing addresses of our members. We’ll open our homes in Madison to house the witnesses. If this destroys CNRA, we will have died for a good cause.”16

The Gromme family had deep connections with old-Milwaukee wealth. Soon, Lorrie Otto would learn just how “old Milwaukee” would respond to the cause.

Lorrie Otto is known for many accomplishments. In the end, maybe it was her willingness to stand up and fight something she felt to be wrong that earned her the most praise. As Don Johnson of the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote to Otto in 1969, after the DDT hearing had ended, “Your energy, enthusiasm, and interest have wrought much. Things have happened which I don’t believe would have without your involvement.”17

When she was inducted into the Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame in 1999, she wore slacks and bright-colored tennis shoes, reminding the audience that she was one of the “little ladies in tennis shoes” derided by a municipal official in battles over the spraying of DDT.18