JOSEPH HICKEY’S OBITUARY LISTED DAN ANDERSON AMONG his survivors. There was no blood tie between the two, but there was a rare personal closeness between the likable graduate student who hailed from North Dakota and the Hickey family. Anderson called himself Hickey’s “academic son.”1 They shared an affinity for bird research, Manhattans, and the Green Bay Packers.

The two got along famously, except, as it happened, when Hickey asked Anderson to go on the great egg hunt. It ended up being the experience of a lifetime for Anderson, even if it nearly cost him his life.

Having sent his set of hypotheses about the cause of steep declines in peregrine falcon populations along to British scientist Derek Ratcliffe, Hickey soon knew what had to be done to confirm the growing understanding that eggshell thinning was at the heart of the matter.

Hickey got the OK from Ratcliffe to share the eggshell hypothesis with other researchers. “So I got on the telephone, and I called Lucille Stickel in Maryland, and had Tony Keith from the Canadian Wildlife Service on the phone, and the three of us talked together, and they knew about it but they didn’t attach as much importance to this as I did,” he recalled. “I immediately got some money from Patuxent to start measuring egg shells . . . and I selected a fellow named Dan Anderson who was one of my graduate students, who was working with me on herring gulls. In [earlier research], we found that Lake Michigan was loaded with DDT or what we thought was DDT. And the herring gulls were loaded. . . . Actually, it was loaded with something besides DDT, it was [also] loaded with a group of compounds called PCBs [polychlorinated biphenyls], which on the gas chromatograph have the same peaks as . . . DDT.”2

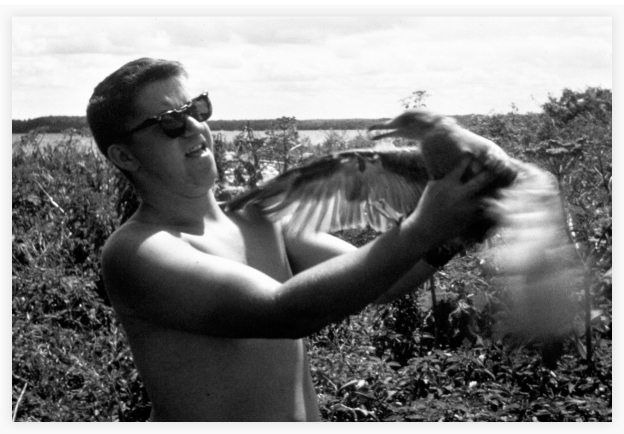

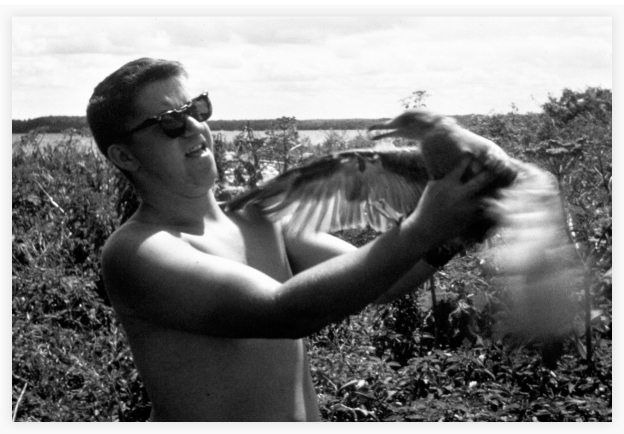

Dan Anderson clutches a herring gull while doing research on DDT concentrations in gulls and other wildlife on Sister Islands, off Door County in Lake Michigan’s Green Bay, in 1967. As a graduate student, Anderson worked closely with Joseph Hickey, a professor of wildlife management at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, and played a key role in providing the link between DDT and the reproductive problems of certain bird species. Photo by Jim Evrard

This clouded the picture. There was a need to find eggshells in other settings, where concentrations of PCBs were absent, and where DDT and its toxic metabolite DDE could be correlated with eggshell thinning. Complicating matters was the fact that eggshell collecting—once a popular hobby—had been banned for half a century in the United States. So museum collections had plenty of eggs from pre-DDT days, some dating to the 1860s, but not many from years coinciding with DDT’s use. There was a need to find eggs that had been illegally collected during the years of DDT exposure.

Hickey turned to Anderson, who had come to Madison straight out of the army specifically to do graduate work under the man who would become his mentor. “I was just a graduate student at the time, and Hickey literally grabbed my hand one day and dragged me over to the engineering department where we talked to an engineer/technician. Joe said we need this and this and that. Several weeks later, our engineer had a perfect little device ready for us to take and measure those tiny holes our peculiar egg collectors made.”

The device was a micrometer, capable of measuring eggshell thickness to a high degree of accuracy. Hickey obtained funding, from a grant in the form of a contract, for Anderson’s travels from Patuxent after speaking with Lucille Stickel. Everything was set. But Anderson was a field guy. He wasn’t excited about the assignment.

“Then Joe and I argued about what I was to do, go to the museums and measure thousands of eggs [Hickey’s plan] or go into the field and sample eggs from populations with different exposure levels of insecticide [Anderson’s wish]. Actually, Joe ended-up letting me do both things, with a lot of help from his extensive network in the ornithological world,” Anderson recalled. “He basically put me on the case, with the advantage of the many, many good ornithological colleagues he had developed over the years. And Joe let me freely snoop around for data and expand our network of contacts, doing all of the traveling and sleuthing myself.”3

The travels were to last for six months straight, and on and off for several more years. “One travel agent in Madison bragged to Joe and me once that the largest ticket ever written by his agency was written for my ‘eggshell travels,’” Anderson recalled.

So Anderson set off for the great museums across the country and some less inviting environs, where egg collectors held their clutches. The year was 1967. Communities across the eastern United States were spraying DDT in futile efforts to control the spread of Dutch elm disease. In Wisconsin, where DDT spraying for the disease was recommended by the Department of Agriculture, citizens in several communities were challenging local authorities over the practice and the results of DDT’s acute toxicity. Anderson’s job was to track down one of the impacts on wildlife stemming from sublethal dosages of DDT.

Years later, Hickey remembered it this way: “What Anderson did was go around to all the museums in the United States [and some in Canada]—to all the major museums—and measure their peregrine eggs as well as the eggs of about 10 other species. I think in the course of that study he measured about 40,000 egg shells. . . . The one thing that Anderson had that I didn’t realize was, I knew that he was a very likeable guy, but Anderson proved to be almost a confidence man. He could charm an egg collector into selling him all his illegal treasures.

“In the course of that tour, he found over 80 sets of bald eagle eggs illegally collected. . . . One or two of them by some very prominent ornithologists. Hmmm. . . . And so, what Anderson found, with the help of these egg collectors was that in 1947, the same year as the change had taken place in Britain [and when widespread use of DDT as a commercial pesticide began], we had an eggshell change in peregrine falcons in Massachusetts and in California, Southern California. So here we had our evidence of a startling change unprecedented in the history of the species.”4

Anderson learned a few other things, too. “I found out through experience that egg collectors were a very curious bunch. I had to gain their confidence, among other things, because many of them had collected eggs illegally. I made sure it was clear we weren’t going to betray their confidence. I made sure that was clear before we got too far.”5

The trick for Anderson was to find the “new stuff,” as he put it. “There was a lot of old stuff in the museums. The new stuff was with guys still out there collecting.” These were the illegal collectors. “I went into some neighborhoods that were a little scary at the time. I’d go knock on the door, and I didn’t know who was going to answer. A lot of them had collected eagle eggs illegally, I remember one guy pulling drawers open. He didn’t want me to open this one door. Well, I opened the door and said, ‘My God, here’s a 1951 bald eagle egg.”

He found a thin-shelled egg in another private collection. Anderson could tell it was dated incorrectly. “I asked him about the date. ‘Are you sure?’ Finally he said, no, he had collected it in 1958.”

In addition to measuring eggs, Anderson was collecting them for Hickey. Once he gained their confidence, he found the egg collectors to be cooperative. “They kind of liked to brag about their stuff. There were only two guys who refused. They didn’t trust me or anybody. They thought I was a government guy.”6

Anderson’s museum and collection tour reached a high point in Camarillo, California. There, he met Ed Harrison, a wealthy man who had established the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology. “He was collecting a lot of stuff, consolidating it,” Anderson recalled. “He had a huge building and a huge office on top of that and was very accommodating. He was an old egg and specimen collector from way back. He had the money to be able to consolidate everything and had probably one of the biggest collections in the world. He gave me his car and truck and turned me loose [in search of egg collectors]. I spent two or three weeks there. That’s where it really started to come together.”7

It’s also where it almost came apart for Anderson.

The California visit was early in his travels, but he had found clear evidence of peregrine falcon eggshell thinning. “I called Joe with the good news, put my data away, and then went out for a drink to celebrate in one of the local bars near UCLA. That night, some crazy SOB that I was drinking with pulled a loaded .45 out and began to wave it about, threatening everybody in the bar.

“For a brief moment, I thought that our monumental discovery and data were going to die right there on the barroom floor. That’s all I could think about, the data. Fortunately, the bartender and I talked this lunatic down. Somehow he had grown to trust me over the evening as I listened to his lamentations about the wife he had tracked from Michigan west to California to kill—perhaps he had trusted me in the same way that those egg collectors with illegal eggs had. The police finally came and took him away sobbing. I am sure that I never told this story to Joe, although I told him nearly everything else from my trips. I didn’t want him to get worried and cut my trips short.”8

Anderson lived, and so did his contributions to the eggshell thinning mystery.