AS JOSEPH HICKEY AND OTHER RESEARCHERS SOUGHT TO make the link between sublethal exposure to DDT and the decimation of some wildlife populations, citizens and local officials in Wisconsin clashed over the chemical’s use in futile efforts to halt the spread of Dutch elm disease.

Some newspaper editorials and opinion columns questioned continued use of DDT in the face of songbird deaths and concerns about human health. Others pointed out the value of elm trees and the costs of removal. Frequently, newspapers carried stories and letters to the editor about DDT dangers in their news columns while advertising DDT products for home and garden use in the same edition.

By 1968, the tide was already turning against DDT, but not based on science alone.

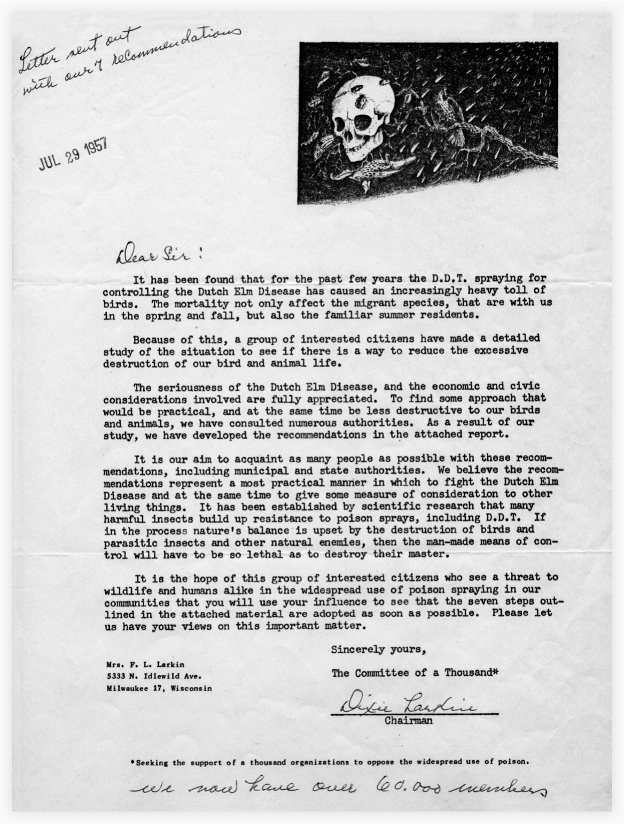

Newspaper clippings of clashes between citizens and elected officials bear out the fact that DDT had already been tried in the court of public opinion. As early as 1957, citizens like Dixie Larkin of Milwaukee had raised concerns about DDT. Larkin was an early environmental activist and a founding member of the Citizens Natural Resources Association.

Bird-watcher Ernstine Brehmer expressed concerns in a letter to the Sheboygan Press in 1960. “Now I am told by the park commission here that my fears are ungrounded, only emotional. But the first year of elm spraying left us with numerous vibrating, painfully dying birds,” Brehmer wrote, calling on other bird-watchers to speak up.1 “For, if this situation is as serious as we suspect, a unified public protest is necessary.”

Dixie Larkin of Milwaukee was an early citizen activist in efforts to curtail the use of DDT. This letter, written by Larkin in 1957, seeks to raise awareness about DDT’s harm to wildlife and asks recipients to follow steps to reduce the pesticide’s impacts. Larkin was an early member of the Citizens Natural Resources Association. WHi Image ID 73092

Clashes between municipal officials and concerned citizens heated up in the mid-1960s, no doubt in response to Silent Spring and, in no small part, to the deaths of songbirds in populated areas.

Cities like Whitewater, Wisconsin, had been using DDT to control mosquitoes almost since its introduction for general use, but the city’s elm-spraying program is what opened citizens’ eyes.2 Mrs. E. Skindingsrude’s letter to the editor that ran in the Whitewater Register on March 28, 1963, was representative of many that would make their way into that popular newspaper forum of the day. “Drenching the soil with deadly poisons is highly destructive to our bird life, which are the natural predators of insects, and how many birds do we see except starlings and some sparrows and pigeons. I haven’t had any chickadees, red or white breasted nuthatches, downy woodpeckers for the last two years. How silent shall our spring be?”3

The city’s officials weren’t convinced that either Mrs. Skindingsrude or Rachel Carson might be right until several years later. DDT use was halted in 1967, as the Whitewater City Council switched to a more expensive but less toxic alternative, methoxychlor.

Overall DDT use was already on the decline by the time these local battles heated up. The La Crosse Tribune editorialized on this topic in 1969: “It is interesting to note that, while the furor is growing over the threat that the pesticide DDT may pose to fish and to mammals including man, its use is steadily declining in some states, including Wisconsin.”4

While DDT’s death knell was eventually sounded based on its overall impact on ecosystems, it’s not likely that city folks would have paid much attention had it not been for Dutch elm disease.

As Dutch elm disease marched across states including Wisconsin, municipalities faced burgeoning costs for the removal and disposal of dead trees. They turned to DDT in an effort to kill the beetles that spread the disease. WHi Image ID 100309

The origin of the Dutch elm disease is unclear. Some sources believe it was native to Asia. Most historical accounts trace its introduction to Europe from the Dutch East Indies in the late 1800s. It is believed to have arrived in the United States in the 1930s on wooden crates made with infected elm wood, but no one knows for sure.5

A fungus spread by both European and native elm bark beetles and also through transmission from one tree to another via their roots, the disease quickly spread across the eastern United States, devastating tree populations.

The American elm had long been considered the ideal street tree. It grew quickly and gracefully, forming canopies that shaded city streets, sidewalks, and yards. Elms tolerated soil compaction and air pollution and were fairly easy to maintain. Because of these traits, an urban monoculture of planted elms existed in many cities. If nothing else, Dutch elm disease pointed out the folly of monoculture planting and helped give birth to a new form of urban forestry that recognized the importance of diversity.

But in the 1960s, the disease decimated tree populations and walloped municipal budgets. Rapid removal of diseased trees that served as incubators for huge beetle populations was one of the best ways to control the disease. It was costly and labor-intensive work.

DDT spraying, on the other hand, offered some success in limiting the disease’s spread by wiping out the beetles. And it was cheap. But even in the best of scenarios, it served only to delay the inevitable.

“I think we were doomed to failure no matter what we did,” recalled Tim Lang, who became city forester in Green Bay in 1961, the year before Dutch elm disease arrived in that city.6 At first, there was no choice but to use DDT. “I’d have been run out of town if I didn’t,” Lang said. “All these people were recommending it.” Like many other municipal officials, Lang was soon caught in the cross fire. DDT’s impact on songbirds caused a vocal backlash. “The Audubon Society was mad. It was quite controversial in the end,” Lang recalled. “There were letters to the editor against what we were doing.”

Those recommending DDT’s use included James Kuntz, a respected plant pathologist at the University of Wisconsin in Madison who was known for developing the popular Wisconsin 55 hybrid tomato, and George Hafstad, plant pathologist with the Department of Agriculture, who “was passionate about saving elms,” Lang recalled.

In a 1966 Wisconsin Department of Agriculture “Dutch Elm Disease Report,” that recommended the use of DDT in fall spraying, Hafstad waxed sentimental: “The Christmas card of President and Mrs. Johnson this year featured ‘the White House on a winter evening with an elm tree in the foreground symbolizing peace and serenity.’ The American elm is intimately associated with the past and typifies much of that which is best in America.”7

By 1966, Dutch elm disease had spread across much of the southern and central counties of Wisconsin, reaching as far west as Eau Claire and Chippewa Counties.

People who were alive during the era of DDT spraying have vivid recollections. Baby boomers remember trailing the mist sprayers on their bikes in a DDT-laden fog in the early days of spraying. Cities often used mist blowers to spray a DDT solution up to one hundred feet into the air to reach treetops. The next day, it was common to find dead and dying birds in the wake of the sprayer. When birds began to die, concerns about possible impacts on human health grew. People were warned to go inside as spraying crews passed by.

Soon, helicopters were incorporated. They were purported to be more effective, directing their payloads more precisely and quickly. But the specter of a helicopter swooping down to drop pesticides was overwhelming for some.

Howard Mead, a retired magazine publisher in Madison, remembered what alarmed him and his wife, Nancy. “The first thing that got us indignant was when our daughter, who was five or six at the time, and other kids were walking to Spring Harbor School along Lake Mendota Drive and helicopters came over and sprayed for Dutch elm and got the kids.”8

Soon, west-side Madison residents were raising a ruckus about DDT. They were vocal and effective, but they were by no means the only protesters in the state.

Milwaukee Sentinel reporter Bill Janz was on hand in October 1965 when Lorrie Otto sprang into action. In a story headlined, “Birds, Bees, Butterflies Case Rests on a Robin,” Janz wrote, “The Bayside village board was offered a frozen robin Thursday night. There was some indication it might accept.”9

Otto told the board the village’s spraying program was killing birds, butterflies, and bees in the village. To determine the exact cause of death, Janz wrote, she told the board, “You’re welcome to one of my frozen robins.” The cost for an autopsy was $60, she added.

Otto had collected dead or dying robins every day for a month the previous summer and had frozen some. She had help, too. Janz reported that “during the summer, she said children brought her convulsing robins, wrens and seagulls in shoe boxes, doll buggies and bushel baskets.” The village president said a committee would likely be appointed to investigate the situation.

The determined Otto would be named to that committee. A few months later, she would be quoted in the Milwaukee Journal saying that, while DDT was saving some elm trees, “in the process of doing it, we’re killing so many other things. In nature, diversity and beauty are synonymous. We’re taking all of this from our lives for elm trees—or for money.”10

Otto wasn’t alone in making alarming claims. Dixie Larkin and others were up in arms in Whitefish Bay. “Several irate Whitefish Bay residents Monday accused the village board of ‘spraying poison on helpless people’ without the people’s consent,” read a February 8, 1966, Milwaukee Sentinel story.11 The Whitefish Bay Herald’s report was a bit more colorful: “Animated protests by alarmed women caused the Whitefish Bay village board, Monday night, to halt its program for helicopter spraying of elm trees.”12

Larkin, a longtime activist, proclaimed to the village board, “The health of my grandchildren or my dog is of much more importance than every elm in this village.” Physician Alice Watts agreed, claiming that “DDT is toxic to the liver.”13

Larkin claimed a friend had to be hospitalized every time the village sprayed its elms.

In response, the board temporarily suspended spraying while the village manager considered Dutch elm disease control options. A week later, Hafstad and University of Wisconsin entomologist Charles Kovalt were on hand to assure the board it was innocent of “spraying poison on helpless people.”14

Not to be outdone by the over-the-top claims from some village residents, Kovalt “pointed out that the death of birds at about the time of DDT spraying also could be caused by the highly toxic chemicals used privately in combating quack grass.”15

As for the residents, Hafstad said his only advice about DDT was, “Don’t drink it.”16

Hafstad’s and Kovalt’s reassurances aside, the skirmishes continued. Bayside put a one-year moratorium on its DDT spraying program for 1966, and Gordon Ruggaber, chair of the citizens’ committee, told a reporter, “We hope some of the birds, fish and cold-blooded amphibians come back.”17 In her files, Otto penned the word “Success!” across the top of the article.18

“At last!” was what she wrote on a copy of a February 22, 1966, Milwaukee Journal editorial that questioned the decisions by three Milwaukee suburbs to use DDT despite disturbing questions raised by reputable scientists and researchers.

A growing sense of discomfort and fear of the unknown was reflected in the editorial: “The worrisome thing about such chemicals as DDT is how little we know of their cumulative effects on wild-life and even on human beings. What little we do know is unsettling. DDT has an awesome ability to persist in toxic form.”19

Despite growing public opposition, twenty-eight municipalities filed notices with the Wisconsin Conservation Department, declaring they would spray DDT in 1966–1967. Some communities, after suspending DDT use in 1966 in favor of the less toxic but more expensive methoxychlor, reversed themselves in 1967 in the wake of heavy elm losses. Some cited concerns about declines in property values due to the loss of trees.20

The city of Milwaukee was among those returning to DDT use. This decision would set the stage for a 1968 lawsuit that would ultimately lead to the DNR administrative hearing.

As cities struggled to control Dutch elm disease they encountered an increasingly agitated public. One news account recalled an uprising in Neenah. The city was scheduled to use DDT in 1966, “but an aroused public jammed city council chambers, signed petitions and waved copies of ‘Silent Spring,’ in a successful attempt to stop the spraying. Some 1970 persons, including 18 Twin Cities [Neenah and Menasha] physicians, signed a petition against the use of DDT in October of 1966.”21

Similar citizen uprisings prompted Janesville to halt DDT use in 1968. “Public Concern Cited as Reason for DDT Reversal,” read a headline in the December 17 Janesville Gazette.

But citizens were getting mixed messages. In a classic clash of state agencies, the Wisconsin Conservation Department had suspended most uses of DDT on state lands years earlier, while the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture and the University of Wisconsin continued to advocate its use in certain settings, including elm-lined city streets.

The Wisconsin Conservation Department became the Department of Natural Resources under a reorganization completed in July 1968. But the old controversy lingered. As the DNR administrative hearing on DDT got under way in December 1968, the Janesville Gazette reported that the Department of Agriculture and the university had reversed themselves and stopped recommending DDT for Dutch elm disease control. However, the decision didn’t affect use of DDT in other settings, such as agriculture.

Clearly, the policy change was a reaction to public concerns. “The effectiveness of DDT in the control program has not been the primary question,” the joint statement said.22 It cited “the significance of persisting DDT residues in the total environment,” and also “public concern and unrest among scientists.” The statement seemed to seek to differentiate between use of DDT for Dutch elm disease and for agricultural and other applications, citing “the general lack of appreciation by the public for the continued need of pesticides in the production of food, fiber and the protection of public health.”

And not all citizens were opposed to DDT. Joseph Wachtel of Wauwatosa took the Milwaukee Sentinel to task for telling the Federal Communications Commission to halt attempts to ban cigarette advertising on radio and TV while calling for a ban on DDT. In a letter to the editor, he wrote, “Now comes along a very respected and mature study on the human body. It shows that smoking and air pollution do severe provable damage to man and his environment. This cannot be said about DDT yet. So here we have your paper calling for the ban of one product condemned on some pretty flimsy evidence and another product far more deadly is OK because a ban would be interfering with commerce.”23

In Madison, Betty Chapman, wife of respected University of Wisconsin entomologist R. Keith Chapman, sought to defend DDT in letters to the editor and, eventually, as executive secretary of a citizens’ group called Sponsors of Science, which fought the ban on DDT. She earned plaudits from Nobel Prize–winning agronomist Norman Borlaug, father of the Green Revolution, who expressed disdain for pesticide foes. As DDT’s fate was sealed in several states and the federal government was moving toward a ban, Borlaug took the time to pen a letter to Chapman, “Thank God some courageous volunteers are getting into the act of fighting back against the propaganda campaign against pesticides and fertilizers, which is based on emotion, mini-truths, maybe truths and downright falsehoods and launched by full-bellied philosophers, environmentalists and pseudo-ecologists.”24

Borlaug’s backing notwithstanding, Betty Chapman was in the minority in Madison.

An aggressive and vocal group of citizens pushed for a halt to DDT spraying of the city’s elms in 1967. Howard and Nancy Mead, whose daughter and her friends had been sprayed with DDT by a helicopter, and the DNR’s Walter Scott were among those who led the effort.

Also involved were writer George Vukelich; University of Wisconsin botanist Hugh Iltis, who would play an important role in the DNR administrative hearing; and Karl Schmidt, whose reading of Silent Spring on WHA public radio’s “Chapter A Day” caused such a stir.25

Perhaps James Zimmerman, a naturalist at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum, summed up the citizens’ concerns best in a March 9, 1967, letter to Mayor Otto Festge. Earlier, Zimmerman had voted in favor of DDT use as a member of the Madison Parks Commission. But he had changed his mind, believing DDT caused too much harm. He wrote: “The birds, bird-watchers, and eventually fishermen, are not the only ones to suffer from present policies, although this is valid reason enough. I do not like to see children, on picking up dying birds, having to be told that (a) nothing can be done for a bird displaying tremors, and (b) the birds must die because we parents are lazy and inept in managing our environment.”26

Festge would recommend the city halt the use of DDT, but the matter was in the hands of the city council. With spraying scheduled to begin soon, City Forester George Behrnd relented, announcing that DDT spraying was being abandoned for 1967. “Behrnd said the decision not to use DDT was not related to the storm of protests that followed his original announcement. He said weather conditions between now and April 1 will not permit use of DDT,” read a newspaper account.27 Despite his announcement, the city council went on with a hearing on whether to ban the use of DDT.

A lot of turf was covered during that March 21, 1967, hearing of the Madison City Council Committee of the Whole, held to allow discussion and debate on the use of DDT, and it was a lively setting. Howard Mead recounted for the city council the story of his daughter’s dousing. Iltis, recalled Mead, “had quite a bit of scientific knowledge. He was colorful, too.”28 Newspaper accounts confirm that. Iltis told the councilmen that the substance would affect all forms of life. He used a comic turn to remind them that DDT accumulated in fat glands. The Capital Times reporter captured it this way: “‘As you sit here tonight on your gluteus maximus you all have some DDT in you right now,’ he told the startled aldermen.”29

Behrnd assured the crowd he was aware of DDT’s hazards but didn’t think his program would cause much harm. The city’s forestry department had fifty barrels of DDT on hand, and using it in Madison’s fifty-square-mile area wouldn’t have much effect, he said. “By next summer, housewives and gardeners will throw out more than that in aerosol bombs in gardens and at picnics,” he said.30

Bringing the Wisconsin Conservation Department31 into the picture, Walter Scott said findings by department scientists and numerous others supported Festge’s recommendation. He identified himself as assistant to the director of the department, and he also represented a group called Mendota Beach Homes. “It is significant that on this first day of spring concerned citizens come before you with a plea to preserve the quality of life this season usually brings.”32

Behrnd’s spraying regime had its supporters. George Hafstad was on hand from the Department of Agriculture, along with two colleagues, department entomologist W. E. Simmons, who also served on the Dane County Board of Supervisors, and John F. Reynolds, also of the Department of Agriculture.

They told the council that until it appropriated enough money for a complete Dutch elm disease program, DDT was the only sensible way to keep the disease under control.

The council was divided on the matter, and the controversy lingered for months. The Wisconsin State Journal recommended continuing DDT’s use. The city was making progress on managing Dutch elm disease, “but a total program to curb the destruction of the elm must include spraying of DDT, according to experts. There is no cure, but DDT will stop the beetles which transmit the disease,” read an August 10, 1967, editorial.33 Answering the lingering question that activists had been asked, the newspaper asserted: “The argument that DDT is dangerous to bird life must be viewed in light of what it would be like for birds if 50,000 elms are destroyed.”

The Madison Audubon Society went on record in opposition to DDT. The Dane County Conservation League also called for a halt to spraying.34 Many of the group’s thousand-plus members were hunters and fishers. Gene Roark, who years earlier had interviewed a tearful Hickey, was its secretary. The Yahara Fishermen’s Club also opposed spraying. As the DDT debate continued, in later years more traditional hook-and-bullet groups took similar positions, in no small part due to findings that fish in Wisconsin rivers and lakes were bearing DDT concentrations.

As the autumn of 1967 arrived, the Madison City Council again faced the question of whether DDT should be used for scheduled fall treatments. After reaching a deadlock a couple of nights earlier, several votes changed on October 26, 1967, when the council voted fourteen to eight to ban DDT use on trees. Zimmerman’s testimony that night, in which he told of changing his mind, was credited with helping sway the vote.35 An expert on plants and especially sedges, he would be inducted into the Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame in 2003.

The Madison battles were well covered by the city’s newspapers. But the same story was playing out in communities wherever DDT was used to control Dutch elm disease. The local battles pitted citizens concerned about the pesticide’s impacts against embattled local officials who were dealing with a devastating and costly disease that was mowing down beloved elms.

The DNR hearing and state and national bans on DDT were still down the road. But the story was unfolding rapidly, and news media across the state and nation was finding the plotline of wonder-chemical-turned-culprit irresistible. DDT was a hot story. Whitney Gould, one of the first female reporters hired at the Capital Times, was interested in the story. She would have her day when the hearing began a year later.

Other events that year would underscore deep divides that remained in the scientific community and turn the spotlight on the impact of DDT on Wisconsin’s precious and valuable fisheries.