In the old Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, near the university’s somewhat ramshackle collection of ancient coins, engravings, and zoological artifacts, crowds of boisterous undergraduates would gather to hear a local celebrity discuss fossils. The speaker was a vicar, but a most atypical one. A stout, balding man with a fondness for outlandish clothes, he was as renowned for his entertaining lectures as he was for keeping a hyena in his back garden. Even by Oxford standards, his reputation was hard to beat.

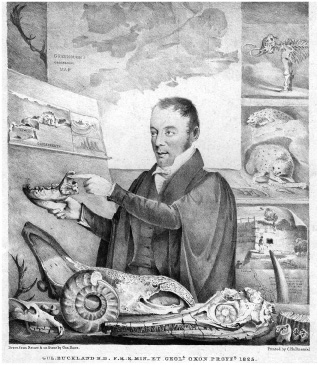

A powerful cleric with Broad Church sympathies, the Reverend William Buckland became reader in mineralogy at the university in 1813. He was described as a “wonderful” speaker whose lectures “overflow[ed] with witty illustrations.”1 As one student explained, he would “enforce an intricate point” with the “Samsonic wielding of a cave-bear jaw or a hyena thigh bone.”2 A portrait of the reverend lecturing in 1823 shows him holding up a hyena’s skull and pointing intently to its ragged jawline. Strewn before him are an ammonite, the skull of an ichthyosaur, and other relics and specimens. Behind, a geological map of England and several sketches, including a depiction of two hyenas hunkered down over recently gnawed bones.

The lectures, which helped to establish Buckland’s reputation at Oxford, showcased his relatively new emphasis on geohistory, which he stretched to include not only “the Composition and Structure of the Earth” but also “the Physical Revolutions that have affected its Surface, and the Changes in Animal and Vegetable Nature that have attended them.”3 With attendees ranging from the bishop of Oxford and various heads of colleges to a gaggle of excited undergraduates, the lectures accented Buckland’s discovery of a large cache of fossil bones in Kirkdale Cave, Yorkshire. These he represented as the remnants of a den of hyenas, since extinct, which he claimed scavenged in northern England until the Flood had wiped them out just a few millennia earlier.

Buckland’s knowledge of geology stemmed, as it did then for many amateur scientists, from frequent excursions on horseback across England to the far reaches of Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. His wife, Mary Moreland, an accomplished artist, would often accompany him. Back home in Oxford, they startled guests by serving such gastronomic delights as badger, beaver, crocodile, and even the odd mole and bluebottle fly.4 The reverend’s bemused colleagues and students greeted such idiosyncrasy with a tolerance unusual for the times, given the conservatism of the university and the controversies that had begun to flare over the still new science of geology.

In his inaugural address as reader of geology at Oxford, commemorating the new position, Buckland tried to reconcile the rift dividing Werner’s and Hutton’s readers. Those following Werner were still committed to arguing that the Flood was universal and relatively recent; they went by the name “catastrophists.” Uniformitarians such as Hutton, on the other hand, focused more on small-scale changes that made the surface of the globe look closer to a “law-bound system of matter in motion.”5

Figure 3. George Rowe, William Buckland, Bachelor of Divinity, Fellow of the Royal Society, Professor [sic] of Mineralogy and Geology at Oxford, 1823, lithograph. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

To downplay that rift, the reverend gave his lecture a bold, even hubristic, title: Vindiciae Geologicae; or, The Connexion of Geology with Religion Explained. Science and religion were for him “inseparable,” he explained in his dedication to the university’s chancellor. Indeed, “the study of geology has a tendency to confirm the evidences of natural religion; and … the facts developed by it are consistent with the accounts of the creation and deluge recorded in the Mosaic writings.”6 Buckland’s Irish contemporary William Henry Fitton described such claims as “scriptural geology,” and not entirely unfairly.7

The Ashmolean Museum, where Buckland gave this particular lecture, has since moved to an impressive neoclassical building. The earlier location, on the city’s Broad Street, was a cramped, slightly dingy two-story building. The first university museum in the world, it housed a number of quirky artifacts, including a stuffed dodo (already an emblem of extinction, and thus of the impermanence of species),8 which by 1755 had become so moth-eaten that it had to be thrown away.9

In Buckland’s day, the Ashmolean took its bearings from the sequence of topics that William Paley described in Natural Theology (1802), a treatise the lively and argumentative clergyman had submitted as “Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, Collected from the Appearances of Nature.”10 In attempting to illustrate Paley’s thesis, the museum made plain its reverence for still earlier forms of creationism, such as those developed by the seventeenth-century English naturalist John Ray, author of The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation (1691).11 “By the Works of Creation,” Ray explained in a later edition, “I mean the Works created by God at first, and by Him conserved to this Day in the same State and Condition in which they were first made.”12

Writing in the aftermath of Humean and Huttonian skepticism (and of the French Revolution), Paley found himself under pressure to curb the religious and philosophical doubt that such work and events had kindled. So he modeled his argument for design on a now-famous analogy—if nature were like a watch, it needed a watchmaker to assemble and organize its intricate parts: “Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation.”13

While Paley’s analogy invoked a long tradition of scholars who found design in complexity and took this intricacy as evidence of God’s existence, complex artifacts do not in fact require a designer (Darwin’s model of natural selection, overturning Paley’s, was devastating for that reason). Still, as Paley believed that arguments for design extended beyond nature to include society, it was, by his reasoning, impious to question a social order that God had ordained. That is also one reason why the philosophes, or intellectuals of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, were blamed for the Revolution in France. For Paley, seeking to overturn their influence, trust in the apparent order and logic of design was critical. “The consciousness of knowing little,” he assured readers, “need not beget a distrust of that which he does know.”14 Faith in the existence of God—evident from the beauty and order of the natural world—would, he argued, take care of everything else.

Despite its reputation today as one of the world’s leading universities, Oxford at the time was by Cambridge and Edinburgh standards distinctly parochial. “All the great intellectual currents of the eighteenth century had swept by” the university, Leonard Wilson notes, “leaving it undisturbed.”15 Edinburgh, like London and Paris, had been “shaken by a new revolution in chemistry, vibrant controversy in geology, [and] new economic, social, and political theories, but these had barely touched Oxford.” At the time, history, economics, and political science “were neither taught nor studied” there. “Natural science had been established [only] in a very small way and was represented by short courses in lectures in chemistry and mineralogy.”16

The establishment of a readership in geology was thus, for Oxford, a significant development—and the inaugural lecture of its first appointee a momentous occasion. The prince regent had endowed the chair, and many university and clerical luminaries had gathered to hear its designated speaker. The Reverend Buckland had to tread carefully, even if that meant backpedaling on difficult controversies and promising listeners that geology, in his hands, would advance Church doctrine, not undermine it.

As Buckland saw it, the study of rocks and the earth, now “exalted to the rank of sciences,” should aim to “unite the highest attainments of abstract science and literature with the much more important purposes of Religious Truth” (VG, 2, 11). The latter would remain its yardstick and final proof. Accordingly, “any investigation of Natural Philosophy which shall not terminate in the Great First Cause will justly be deemed unsatisfactory” (VG, 11).

The purpose of making such pronouncements was largely to handcuff geology to scripture. That was no problem to Paley and like-minded Evangelicals, not least because, as the Victorian preacher and polemicist John Charles Ryle later explained, “The first leading feature in Evangelical Religion is the absolute supremacy it assigns to Holy Scripture, as the only rule of faith and practice, the only test of truth, the only judge of controversy.”17 Consequently, the doctrinal and scientific reach of Evangelical creationism was (and, for many such believers, remains) limited to confirming the veracity of Genesis, whose opening verses rank among the Bible’s most poetic.

Buckland, evidently, was eager to compete with them. Although his argument and thinking were more sophisticated than Paley’s, he garnished his lecture with comforting metaphors, including that nature’s “new kingdom” (VG, 11) gives us “genial showers [that] scatter fertility over the earth” (he declined to mention the frosts and droughts that also harden it). The world gives us “never-failing reservoirs of … springs and rivers” to water our crops, Buckland added, ignoring the world’s vast stretches of desert where rivers and rain are scarce. In these examples, he declared, “We find such undeniable proofs of a nicely balanced adaptation of means to ends, of wise foresight and benevolent intention and infinite power, that he must be blind indeed, who refuses to recognize in them proofs of the most exalted attributes of the Creator” (13).

The implication that skeptics and nonbelievers were blind pales beside Paley’s tactic of openly questioning their sanity. To contend that “the present order of nature is insufficient to prove the existence of an intelligent Creator” is, Paley asserted, to advance “a doctrine, to which, I conceive, no sound mind can assent.”18

Within a decade, such unfortunate rhetoric would backfire, leaving Paley and Buckland sounding a lot more self-satisfied than their arguments and research warranted. Regarding his own quite basic and tautological explanation for geological formations, for instance, Paley insisted that he was not “under the smallest doubt in forming our opinion.”19

It was of doubt precisely that Paley hoped to rid the world. So he turned the tables on skeptics and secularists, distorting their arguments by claiming that if God were not involved at every stage of creation, then we must somehow revert to the “opposite conclusion … that no art or skill whatever has been concerned in the business.” Asking rhetorically, “Can this be maintained without absurdity?” he replied, “Yet this is atheism.”20

In hopes of countering the deist argument that God created the world once, then retired to let nature take its own course, Buckland ended up skating on thin ice: “When therefore we perceive that the secondary causes producing [the earth’s] convulsions have operated at successive periods, not blindly and at random, but with a direction to beneficial ends, we see at once the proofs of an overruling Intelligence continuing to superintend, direct, modify, and control the operations of the agents, which he originally ordained” (VG, 18-19). Presumably, the reverend had forgotten the horror and devastation of the Lisbon earthquake, including its effect on Christians struggling to explain why a God responsible for secondary causes would allow such atrocity to annihilate some of his most devout followers.

But Buckland’s Vindiciae Geologicae was forward-thinking on one matter. It took a risk in trying to formalize “gap theology”—the notion that a large historical interval separates the first and second verses of Genesis. Accordingly, a long stretch of time could fall between the initial creation (“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth”) and the earth’s ongoing amorphousness (“And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep”).

To Buckland, then, the word “beginning” in Genesis referred to an undefined period before man, when the newly formed earth bore numerous plants and animals that had since become extinct. He was thus able to incorporate his own catastrophism theory—the notion that a global deluge had devastated all planetary life except the last remaining species that Noah had carefully rescued—into a version of Old Earth creationism. He could do so without resorting to biblical literalism or, just as critical, without offending the powerful clerics who had gathered to hear his inaugural lecture. “We argue thus,” he declared, in a syllogism framed by a rhetorical question: “It is demonstrable from Geology that there was a period when no organic beings had existence: these organic beings must therefore have had a beginning subsequently to this period; and where is that beginning to be found, but in the will and fiat of an intelligent and all-wise Creator?” (VG, 21).

There was, he insisted, only “apparent nonconformity” between geological research and popular understanding of the Earth’s creation—just as there was only an “apparent inconsistency” between “tangible facts” and “literal interpretation of Scripture” (VG, 22, 23). Accordingly, the hiatus in historical time between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2 that Buckland accepted did not, for him, represent a problematic gap between the poetry of the Bible and the increasingly rigorous prose of science. The Church of England showed its support for that argument by later appointing him dean of Westminster.

Although it took him decades to accept the full consequences of Buckland’s thinking, the reverend’s admiring student Charles Lyell, taking inspiration from his lectures, quickly grasped that if geology was to advance, its practitioners must “free the science from Moses.”21 To Lyell, a devout Unitarian (who views God as one rather than encompassing the Trinity), that task initially seemed easier to accomplish in theory than in practice. He could accord the planet and its species a capacity to evolve and adapt, yet understandably found that ability distasteful, even repugnant, when taken to its logical conclusion and applied also to man. The idea that we too have evolved—that man descends from such near neighbors as the “Ourang-Outang”—was a conclusion from which Lyell privately recoiled. Cognizant of his stature in the field, however, as well as the growing need to respond to proponents of species development such as Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Lyell’s many admirers tried to force him to take a stand.

The ensuing struggle, including its theological consequence and psychological price, came down to how much doubt Lyell and his argument could bear. Suffering intense anguish over faith and growing evidence of species development from fossil records, Lyell tried to maintain a convincing front. He offered such bravura declamations of Lamarck’s and others’ early theories of evolution that, for many Victorian intellectuals, Lyell seemed to settle the debate. Only in private did he concede that the question of evolution (then known as species “development” or “transmutation”) troubled him, not least because he staked much of his career on its not being a possible outcome for man.

The gap that divided Lyell’s public scientific statements from his private and religious doubts about them is to a large degree intensely Victorian. It encapsulated a profound, almost foundational anxiety that haunted many of his contemporaries, including Thomas Carlyle and, later, Leslie Stephen. In the process of following their journals, letters, and works, we witness a fascinating set of relays between science and literature, where fiction transforms—as it tries to make sense of—the scientific theories that detractors and supporters fiercely contested at the time. It is less often acknowledged that science itself was strongly influenced by metaphors that Victorian culture popularized, including its sublime images of time.

Lyell’s evocative style helps to explain that influence. His use of literary figures conveys the impact of scientific arguments about the expansiveness and immeasurability of the universe. Indeed, his arguments and works not only drew in large numbers of general readers but also captivated the imagination of such writers as George Eliot and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who invoked him, respectively, in The Mill on the Floss and In Memoriam.

Rather like Darwin, Lyell earnestly (if incompletely) engaged with evolutionary theories that he for a long time disbelieved. For that reason, his work cannot be dismissed as having been offered in simple bad faith, as at least one contemporary critic has charged.22 The issues at stake are more complex, including doubt, resistance, denial, and, finally, grudging concession. At stake, after all, was nothing less than the history of the planet and of Homo sapiens as a species. Small wonder that Lyell painstakingly worked out hypotheses to their logical conclusions, trying earnestly to make them fit evidence that pointed in a different direction.

Lyell made no pretense of “connecting” geology with scripture, as Buckland had. He made clear that his geological statements would succeed or fail on their own merit, giving Principles of Geology a subtitle that sounded scientific and secular, and certainly humbler than Buckland’s: “An Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation.” That stress on looking backward from current evidence, which Hutton’s Theory of the Earth had popularized, made clear from the start that Lyell saw geological developments as continuous with the past, rather than as ending with Moses’ account of the flood besieging Noah, or God’s proclamation after the deluge: “I will not again curse the ground any more for man’s sake” (Genesis 8:21).

To Lyell, the world presented an exciting array of cryptic signs and buried stories that were archived in its crust and in fossils, if the geologist could but discover and decipher them. Geology, in his hands, became a new way of seeing and reading, based on the evidence. And scientists had misinterpreted that evidence (Lyell let his readers infer) because the Bible had steered them down a different path. Another world awaited them that was older and stranger than most of them realized. As he declared, in a sentence capturing his literary style, “We may restore in imagination the appearance of the ancient continents which have passed away.”23

Lyell’s desire to foster an archaeology for the planet, based on a cyclic history of the Earth, had dizzying philosophical implications that made him “venture to doubt” various “article[s] of faith” (PG, 16)—the global effects of Noah’s flood being one of them. Picking up where Hutton had left off, with his poetic but thoroughly disorienting assertion, “We find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end,” Lyell produced an argument for “deep time” that underlined the immensity of the planet’s history.24

Figure 4. John and Charles Watkins, Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Bt, albumen carte de visite, 1860s. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Just as Hutton had, Lyell discovered that his cyclic view of that history raised large questions about extinction, a serious conundrum for both scientists, given their respective arguments and beliefs. Why indeed would God create species to flourish, only to render large numbers of them extinct? Was that a sign, as Hutton had wondered, of a deliberate flaw in God’s model or an indication that he was letting nature take its own course? And if the latter, what were the implications, for humanity as for Christianity, of a dynamic—even hostile—model of nature, which let whole species disappear without apparent reason?

“Whereas Hutton had confined himself almost entirely to processes of inorganic change,” John Greene notes, “Lyell defined geology to include the study of organic change as well. This was in keeping with the progress made in the study of the fossil record since Hutton wrote.”25 But the inclusion posed a serious intellectual and religious challenge, forcing Lyell either to accept that evolution affected all species or else to maintain, against all evidence, that humanity was exempt from such changes.

“Although we are mere sojourners on the surface of the planet, chained to a mere point in space, enduring but for a moment of time,” he declared as optimistically as he could, “the human mind is not only enabled to number worlds beyond the unassisted ken of mortal eye, but to trace the events of indefinite ages before the creation of our race, and is not even withheld from penetrating into the dark secrets of the ocean, or the interior of the solid globe” (PG, 102; emphasis mine).

Instead of turning to scripture and trying to confirm its scientific bona fides, then, as Buckland and Paley had done, Lyell allowed the present to recede like a series of infinitely diminishing Chinese boxes—except that, in his poetic analogy, the boxes became earlier epochs: “Worlds … seen beyond worlds immeasurably distant from each other, and beyond them all innumerable other systems are faintly traced on the confines of the visible universe” (PG, 16). If one could somehow trace their line to a vanishing point, one probably would not alight at an end or beginning; but the act of working backward would produce a history. It would forge a connection, however tenuous, between that moment, light-years ago, and now.

The recourse to simile and metaphor was no accident. “Deep time” doesn’t anchor meaning in the way that Genesis does; it leaves science with a host of questions, including over the reliability of its claims and calculations. With centuries and millennia as hopelessly inadequate measurements, the intervals of space involved become so sublime that the mind can find no reasonable scale for them. As Lyell put it lyrically, describing his reaction to reading Hutton, “The imagination was first fatigued and overpowered by endeavouring to conceive the immensity of time required for the annihilation of whole continents by so insensible a process [as minute, protracted sedimentation and erosion]. Yet when the thoughts had wandered through these interminable periods, no resting place was assigned in the remotest distance” (PG, 16).

One of the crises stemming from Hutton’s work was, sure enough, that it seemed to distance (even, potentially, to remove) from the Earth’s history the presence and reassuring intervention of a beneficent architect. The planet underwent changes without apparent rhyme or reason. If a blueprint for the universe existed, other than what was written as scripture, then it was becoming increasingly difficult to find it. Still, as Adrian Desmond asserts persuasively in The Politics of Evolution, the fact that Lamarck’s theory of evolution put creationist explanations on the defensive was precisely a source of its appeal to atheists and socialists who in the 1820s and 1830s “supported a brand of evolution … far more radical than anything Darwin envisaged.” “Theirs was evolution in a real ‘revolutionary’ context,” he explains, promoted by those wanting “the dissolution of Church and aristocracy, and calling for a new economic system.”26 In later chapters, we’ll see how this groundswell of support for pre-Darwinian evolution helped to make the topic more acceptable to middle-class readers concerned about being labeled “infidels” and “atheists.”

The absence of an apparent blueprint for creation (beyond Genesis) provoked a different reaction in scholars such as Lyell, whose response to such doubt-filled moments (anxious misgivings followed by hesitation and, eventually, disbelief) soon developed into a pattern. “In the course of my tour” of volcanic Mount Etna on Sicily, he acknowledged, “I had been frequently led to reflect on the precept of Descartes, ‘that a philosopher should once in his life doubt everything he had been taught.’” But he neither welcomed that doubt nor allowed it to permeate all that he knew: “I still retained so much faith in my early geological creed,” he added, that “when visiting… parts of the Val di Noto … all idea of attaching a high antiquity to a regularly stratified limestone … vanished at once from my mind.”27

Given all of the evidence that he could muster for the planet’s longdrawn-out development, including that the flood affecting Noah was almost certainly limited and not especially unique, Lyell also found his thoughts returning increasingly to the species question. It was rapidly becoming the hot-button issue of the time, a heated subject for Sunday sermons and religious treatises, as we shall see. With Lyell’s reluctant help, science increasingly put the burden of proof on Christianity. For if uniform changes were visible everywhere, including in the extinction of species, what—other than biblical insistence—made us exempt from the transmutations affecting almost everything else on Earth?

The faithful argued passionately that God had singled us out, giving us temporary dominion over the planet. And perhaps surprisingly, given his bid to “free [geology] from Moses,” Lyell held a similar belief for much of his career.28 A scientist who generally preferred appeasement to conflict, he shied away from theological controversies, not least because he still had to make a living.29 Alienating the clergy could end one’s chances of being appointed a professor at Oxford or Cambridge (Lyell ended up at the University of London). Indeed, in ways that distinguished England from its European counterparts, clerics tended to control university appointments. (At Cambridge, amazingly, the professoriate also had to agree to be celibate, though exceptions were sometimes made to those already married.)30

The Reverend Henry Milman, one of Lyell’s closest associates, became an unwitting victim of such parochialism. Milman’s History of the Jews (1830) was too cutting-edge for the time. It drew on German biblical criticism to argue that the Jews were an “eastern tribe” and on documentary evidence to downplay the existence of miracles.31

Ultimately, nothing in Milman’s book “went beyond what could be found in the notes to an expensive Bible edited by one of his most learned opponents.”32 Yet it was widely denounced, by Sharon Turner, author of the hugely popular Sacred History of the World (1832), as by the young John Henry Newman, subsequent leader of the Tractarians, Oxford’s Anglo-Catholic movement. “The crime,” Lyell noticed, was “to have put” such arguments forth “in a popular book.”33 Milman’s work appeared in John Murray’s relatively inexpensive “Family Library” and seems, incredibly, to have generated more heat because it was written largely for a lay audience.

Lyell resented such control and narrow-mindedness. He envied the United States its nondenominational universities and railed (to friends, at least) that England was “more parson ridden than any [country] in Europe except Spain.”34 As Roy Porter acknowledges, Lyell criticized not only “‘theological sophists,’ Catholics, Puseyites, and Scriptural geologists like Andrew Ure (’an unprincipled hypocrite and libertine’ …), but [also] Anglican bishops, the hierarchy of the Church of England, and ecclesiastical power in general.”35

Private denunciations of clerical power are not, however, the same as a public stand against it. Although Lyell was an ardent liberal Whig who advocated electoral reform and the disestablishment of the Anglican Church, he also had his own beliefs, which he seems to have kept quite separate from his criticisms of organized religion.36 Those beliefs surface at the end of Principles of Geology, in a closing sentence that underscores—perhaps with Milman’s fate in mind—that speculating on the Earth’s beginning “appears to us inconsistent with a just estimate of the relations which subsist between the finite powers of man and the attributes of an Infinite and Eternal Being” (PG, 438). Lyell’s Unitarian beliefs do not make him a conventional doubter, yet his intellectual difficulty in squaring those beliefs with scientific arguments he contested and even ridiculed makes him quintessentially Victorian and a key source of interest for this book.

Lyell ended up backloading quite a lot into Principles. One sentence earlier, he had added rather hurriedly, as if gliding over a long-postponed subject, that although “it appears that the species have been changed” (the passive clause carefully abstaining from any suggestion of how or why), “yet they have all been so modelled, on types analogous to those of existing plants and animals, as to indicate throughout a perfect harmony of design and unity of purpose” (PG, 438).

The argument could almost be a throwback to Paley’s Natural Theology. Yet Lyell’s claim, read carefully, concedes far less than it may at first seem. As James Secord observes, “In the Principles the rock of faith rest[s] solely on God’s maintenance of the economy of nature and on the status of humans as moral, rational beings.”37 Lyell had thus chiseled away quite extensively at Paley’s arguments.

But he had to keep the plank in place—in part because religious arguments about the Earth’s creation still had so much meaning for him. Only in the closing pages of his three-volume study could he be “led with great reluctance into [a] digression” on Noah’s flood (PG, 433). Tiptoeing around that delicate subject, the cause of so much rancor and so many column inches at the time, he wrote that in all likelihood it was a localized flood that had taken place near what we now call the Black and Caspian Seas. There, subsidence—perhaps even an earthquake—had made possible the sudden release of large amounts of water from much higher ground.

Lyell’s distaste for using secular explanations to settle theological disputes is palpable, not least because the former had such an unsettling effect on his convictions. As Michael Bartholomew observes, he “subscribed to the specifically natural theological opinions of his contemporaries, even though Principles was seen by some of them to embody a denigration of those beliefs.”38

Lyell was quick to intuit how much shock and dismay his words would cause other believers. (Moses’ account of the Flood had called it global; to limit the Flood to even a relatively small geographical region was a major, and controversial, step.) His faith and propriety also led him to conclude that religion was a private affair between oneself and God. That conclusion —mealy-mouthed to some—gave belief a sacrosanct dimension, which, in his view, science should either abstain from encroaching on or do so only with great reluctance and respect.

When for instance the atheistic Scots physician George Hoggart Toulmin decried Christianity in The Eternity of the World (1785), Lyell privately compared him to English soldiers who had raided Burmese temples for war trophies: “To insult their idols was an act of Christian intolerance, and, until we can convert them, should be penal. If a philosopher commits a similar act of intolerance by insulting the idols of an European mob (the popular prejudices of the day), the vengeance of the more intolerant herd of the ignorant will overtake him.”39 Attacking beliefs that the “mob” was not willing to give up “is not courage or manliness in the cause of Truth,” Lyell insisted. “Nor does it promote its progress.”40 He was doubtless right on that last count. While allusions to a European “mob” and an “intolerant herd” betray prejudices of his own, Lyell grasped that people are extraordinarily reluctant to relinquish their beliefs. In some cases, they would prefer to die for them than abandon them, and certainly not see them attacked gratuitously.

The strongest bone of contention among Lyell’s critics—and the clearest sign of his difficulty in parting with certain long-held beliefs—was his long-delayed acceptance of evolutionary theory. The issue turned into a drama of exceptional significance for Lyell, not least because he devoted so much of his career to refuting it.

“It cost me a struggle to renounce my old creed,” Lyell later acknowledged in 1863.41 That was putting it mildly. It would take him almost three decades of contemplation and hedging (with numerous updated editions of Principles and the publication, finally, of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species) before he would quietly end that fight and bow to what had become inevitable. He did so, justifiably, claiming some credit for bringing about the new state of affairs. Certainly, Darwin was prepared to concede that he had been unfair to Lyell—that there was much more in Principles than he had given his friend credit for—though he was still disappointed in Lyell’s long-drawn-out resistance to evolutionary theory.42

Lyell first encountered arguments for species “transmutation” in 1827, when he read a borrowed copy of Lamarck’s Philosophie zoologique. That study, which outlined a fairly basic theory of organic descent for all creatures, including man, had appeared in Paris almost two decades earlier. Lyell’s reaction, at least to his friend Gideon Mantell, was dismissive, comparing the work to light fiction. The book had delighted him “more than any novel I ever read,” he scoffed, “and much in the same way,” because such theories “address themselves to the imagination.”43

Certainly, such theories do affect the imagination—just as Lyell’s account of “deep time” forces us to wrestle with the concept of infinity. Behind the scenes, however, Lyell found Lamarck’s argument extremely unnerving. In Principles he voices surprise that it “has met with some degree of favour from many naturalists,” not just in Paris but also among such London colleagues as Robert Edmond Grant, a member of the Geological Society Council who taught fossil zoology at the city’s university.44 Even in his 1827 letter to Mantell, Lyell admits, in barely concealed horror, that if Lamarck were right, his theory “would prove that man may have come from the Ourang-Outang.”45 The chaos and confusion to ensue would be too awful to imagine—a theme that recurs with almost painful repetition in Lyell’s notebooks far into the 1850s. In the following statement to Mantell, for example, it is not immediately clear if he is voicing an exclamation or asking a heartfelt question: “How impossible will it be to distinguish and lay down a line, beyond which some of the so-called extinct species have never passed into recent ones.”46

In public, Lyell regrettably decided to play to England’s rearguard audience, which was only too happy to dismiss the latest intellectual fad from Paris. In 1832, London’s Monthly Review derided “transmutation” as “the most stupid and ridiculous” idea to have been hatched by “the heated fancy of man.”47 Lyell was neither so brash nor so foolish, but he did sniff in Principles that Lamarck’s arguments “were not generally received” before almost going out of his way to attack them as “staggering and absurd” (PG, 184, 189). “When Lamarck talks ‘of the efforts of internal sentiment,’” he jeered, “he gives us names for things, and with a disregard to the strict rules of induction, resorts to fictions, as ideal as the ‘plastic virtue,’ and other phantoms of the middle ages” (188).

Criticizing Lamarck’s theory as “fiction” and the effect of an overheated “imagination” was becoming almost a trademark reaction. Yet the charge of antiquated thinking closely fit Lyell here. And the theory that he publicly ridiculed preoccupied him, with implications he could neither accept nor dismiss. “The chief objection to the hypothesis of transmutation,” he privately acknowledged in his journals, “was naturally the inseparable connexion which it established between Man & the lower animals.”48 “If we exclude” man from transmutation, he worried in 1856, three years before the “earth-shaking” publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, “the only sound argument for the popular theory of progress in the organic World is gone. If we include him, the great book which the Geologist is trying to decypher becomes at once identified with Natural Theology as well as with Natural History.”49

Caught between this Scylla and Charybdis, Lyell settled uncomfortably on the compromise that man is “an exception” to progressive development. Like many Victorians, he saw evolution as degrading, even disgusting—a process not befitting a noble species. That reaction is understandable, given the newness of the theory and the shock of wrestling with its far-reaching implications. Evolution also brought to Lyell’s mind fears about barbarousness, miscegenation, and even sexual corruption: “If Man be modern,” his notebook frets, “& if the negro & white man have come from one stock, & if such distinct races, if discovered in quadrumana, would have been pronounced species, then new species have been formed since the human pair originated.”50

Those worrisome “ifs” highlight a religious scientist struggling to accept the almost unavoidable conclusion: “new species have been formed since” Adam and Eve. If in a strict biological sense we are no longer the same as the first “human pair,” then what are God’s intentions for us, Lyell wondered? If we have evolved in ways similar to other species, then were Adam and Eve somehow imperfect to begin with, and do we nonetheless hold a specially appointed task, with dominion over other creatures?

After the cornerstone of Lyell’s faith began to shift and he could no longer call man “the crowning link in the chain of progressive development,” a slew of questions hit him almost immediately:51 “If there are … intermediate steps between the sensible or rational & the insane, why claim such dignity for Man as contrasted with the brutes. When does the sucking infant attain the rank of an intelligent dog? Has the child an hour before its birth a soul? Or an hour after?”52

After Lyell allowed himself to entertain such questions, the dam seemed to break. A flood of queries followed, about insanity, idiocy, and especially race. There’s no avoiding that Lyell’s anxiety about evolution was coextensive with his prejudices over what he called “the hundreds of millions of savage or semi-barbarous races.”53 Those questions, in turn, generated still more unanswered enigmas. “Then comes the question whether less civilized races deteriorated from a more highly gifted or more advanced race, or whether the first stock was of low capacity & improved into higher.”54

“Not only did evolution repel Lyell’s highly refined aesthetic sense,” including his image of humanity, notes James Secord astutely; “it [also] undermined his lofty conception of science as the search for laws governing a perfectly adapted divine creation.”55 That Lyell abstained from public commentary on this issue did not end his profound unease over man’s “bestial” origins. As he put it in November 1858, “If the geologist… blends [man] inseparably with the inferior animals & considers him as belonging to the Earth solely, & as doomed to pass away like them & have no farther any relation to the living world, he may feel dissatisfied with his labours & doubt whether he would not have been happier had he never entered upon them & whether he ought to impart the result to others.”56

The full intensity of Lyell’s “repugnance”—his word—at perceiving that men “may have come from the Ourang-Outang” was enough to make him doubt his role as a geologist. As his private notebooks confirm throughout the 1850s, such emotions were as real and painful for a devout scientist as they were for men of the Church who firmly believed that science and religion were not drifting apart but could in fact hold together.

As Lyell eventually acknowledged to himself, such weighty matters “evinced… something more than mere philosophical doubt.”57 They hung invisible question marks around everything that he had come to believe about man’s privileged role on earth, with the universe still a beneficent entity designed to assist us. Science had begun to turn such assumptions into reflections of a demand for the universe to make sense, with humanity somehow still at its center as “Time’s noblest offspring,” to quote Bishop Berkeley’s words from roughly a century earlier.58 But as Lyell eloquently observed, the mounting contrary evidence still left “mankind in the same state of aspiration & hope, of trust in God, of yearning after something higher yet to come, of a feeling of individuality, [and] a belief that the discarding of this would not only lower the hopes but deteriorate the moral standard—that a belief in immortality betters & renders happier & is therefore more probably true than a philosophy which teaches that we are bubbles reflecting for a moment the wonders of the universe & then bursting & returning to annihilation.”59 One could hardly ask for a more lyrical statement of what religion is designed to achieve. Nor is one likely to read a more articulate account of what believers still ask religion to make possible. For Lyell, though, to state that belief in immorality bettered humanity and was “therefore more probably true” than a philosophy teaching otherwise makes clear where religious faith collided with his commitment to scientific evidence. Unsurprisingly, then, the more he brooded on those questions, the less they satisfied him. His notebooks are full of statements about living almost unavoidably in “a state of doubt,” and doing so in great discomfort.60

As he continued to attend church fairly regularly, Lyell was “given to thoughtful and agonizing reflections” on the ever-widening gap between scripture and evolution. As his biographer Leonard Wilson put it, Lyell “couldn’t quite accept the consequences of a chaotic and meaningless universe,” even though his geological theories pointed almost unavoidably to that conclusion.61

“There was a real agony in his mind over religious doubt,” Wilson continued. “I think he always had doubts,” both intellectual and religious, and tried as hard as possible to reject them, “but the doubts were always at the back of his mind.”62

Tennyson, future poet laureate, famously would invoke Lyell’s Principles in his elegy In Memoriam (1850), by far the Victorians’ most popular poem, especially the corrosive effect of Lyell’s expansive notion of time, change, and periodic extinction on “our little systems” (philosophy, science, and theology). “From scarped cliff and quarried stone / [Nature] cries, ‘A thousand types are gone: / I care for nothing, all shall go.’”63 It is nature, “red in tooth and claw,” whose “evil dreams” cause Tennyson’s speaker to “stretch lame hands of faith, and grope.” For it is nature—alien, violent, and indifferent—that has “shriek’d against [man’s] creed,” in particular his ardent belief that love is “Creation’s final law.”64 Tennyson felt moved to voice such anguish and religious uncertainty despite his wanting to bolster faith that everything would work out well in the end:

Oh yet we trust that somehow good

Will be the final goal of ill,

To pangs of nature, sins of will,

Defects of doubt, and taints of blood;

That nothing walks with aimless feet;

That not one life shall be destroy’d,

Or cast as rubbish to the void,

When God hath made the pile complete.65

Tennyson was not, of course, the only writer influenced by Lyell. Among others, George Eliot almost openly invoked his Principles in The Mill on the Floss when her narrator asserts: “To the eyes that have dwelt on the past, there is no thorough repair.”66 However, one key Victorian intellectual, Thomas Carlyle, dismissed Lyell, calling him, in his own inimitable way, “a twaddling circumfused ill-writing man.”67

The invective seems intense even for Carlyle, until one recognizes the two men’s shared struggle with evolution. Just as Lyell had, Carlyle wrestled with the principle, calling it a “most melancholy doctrine” that helped shear his religious beliefs.68 Also like Lyell, he added, “Faith is properly the one thing needful.” Hence “the loss of … religious belief was the loss of every thing [sic].”69 Although that last part may carry more autobiographical weight than Carlyle intended, he found living without faith extremely difficult and sensed, correctly, that others were suffering similarly.

Figure 5. Julia Margaret Cameron, Thomas Carlyle “Like a Block of Michael Angelo’s Sculpture,” albumen print, 1867. © National Media Museum/Science and Society Picture Library, London.

A fellow Scot also brought up in a strict religious environment (Calvinist rather than Unitarian), Carlyle began writing Sartor Resartus, one of the era’s most powerful statements on doubt, two months after the first volume of Lyell’s Principles of Geology appeared.70 By November 1833, only weeks after Lyell released his third volume, Carlyle’s study had begun to be serialized. So completely do the two works overlap, indeed, that Carlyle opens Sartor with allusions to Lyell’s geology and complaints about its philosophical implications. “Of Geology and Geognosy we know enough,” he quipped in his proto-Joycean style; “what with the labours of our Werners and Huttons, what with the ardent genius of their disciples, it has come about that now, to many a Royal Society, the Creation of a World is little more mysterious than the cooking of a Dumpling” (SR, 3).

The dig was clearly intended as a punch. An ever more querulous social critic, Carlyle was angry that the “Torch of Science” had been so “brandished and borne about” that the mystery of life had begun to leech (SR, 3). “Man’s whole life and environment have been laid open and elucidated,” his fictional editor opines; “scarcely a fragment or fibre of his Soul, Body, and Possessions, but has been probed, dissected, distilled, desiccated, and scientifically decomposed” (4).71

Intended as a new kind of book that “glances,” in Carlyle’s words, “from Heaven to Earth & back again in a strange satirical frenzy,” Sartor Resartus, Carlyle’s most scriptural text, is scarcely read or taught today.72 “A strange Book all men will admit it to be,” its author predicted.73 In an almost self-fulfilling prophecy, it has come to be known as the Finnegans Wake of the Victorian era: amazing—even astonishing—in scope and originality. Yet so baroque in style and meaning that we scarcely try to fathom why it influenced large numbers of writers from Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and George Eliot to Thomas Hardy, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf.

Carlyle did himself no favors with his quirky style and the book’s uninviting title (literally, “The Tailor Retailored”). Yet his experiment is not half as difficult to read as its reputation suggests; and its quasi-religious speculations generate such extraordinary meditations on doubt that its hapless protagonist, an imaginary German professor, is pushed to the limits of his belief and identity. Carlyle, in short, has important things to say about faith.

“The role that Calvinism plays in Sartor Resartus,” his editors allow, is “difficult to overstate.” That is partly because Carlyle was immersed in the religion from a young age. With his parents austere Calvinists, proud of their work ethic and fiercely held beliefs, the “daunting presence of God and Kirk was an everyday reality… [and Carlyle] revered the belief while holding the institution suspect.”74

He had studied theology at the University of Edinburgh, with every intention of becoming a minister of his church. His father strongly encouraged him, and Carlyle seemed to comply. But doubt about his faith and direction intensified as he read. He ended up rejecting theology and with it the prospect of a future in the church.

Still, long after he had ceased to believe in Christianity as an organized religion, Carlyle (like many others) found that he couldn’t give up the church completely. “The religious faith in which he had been brought up disintegrated,” one of his biographers notes, “before the challenge of the newer and, it seemed, more sophisticated creed” began to irk him: the rationalism of the Scottish Enlightenment, with its skeptical debunking of religion.75 So even though Carlyle’s semiautobiographical Sartor Resartus was “a classic expression of crisis in faith,” its author remained both inspired and tormented by what he could not quite renounce.

“To accept the tenets of Calvinism was impossible,” his editors explain, “yet to reject them was equally impossible. Just before the composition of Sartor Resartus, he considered testing his notions of theology by writing a biography of Luther.”76 Indeed, even in its profound expressions of doubt and religious confusion, Sartor is permeated by various kinds of religiosity —transcendentalist philosophy, belief in the power of symbols, and even ardent devotion to work. Carlyle talks about that as part of the “after-shine” of Christianity: the religion affects one long after one has stopped believing and worshipping (SR, 124).

Carlyle’s protagonist balances similar tensions. His name, the peculiar-sounding “Diogenes Teufelsdröckh” (literally, God-Born Devil’s Dung), implies an almost Manichean split between his Hellenistic first name and his Hebraic last name. With his erudition and profession, moreover, Carlyle’s hero is “a distillation of the intellectual traditions of the German professor and the rhetorical traditions of the rabbi.”77 Indeed, there are several hints in the text that Herr Teufelsdröckh, educated in the Midrash at the University of Weissnichtwo (Don’t Know Where) is Jewish, albeit in ways we would now call secular.

The text’s religious complexities don’t end there. As the editors point out: “To the Old Testament mind (Sartor), the answer is “Yes” to [Teufelsdröckh’s many] questions of faith. However, to the New Testament mind (Resartus), the answers are not so clear.”78 There is, in short, no neat balancing of Old and New Testament perspectives. On the contrary, everything biblical in Sartor, though respected, ends up slightly jumbled. Remnants of faith remain, but the book ends on a question mark, suggesting that it “does not pretend to contain any ultimate truth,” religious or otherwise.79

Teufelsdröckh is a bit like a wayward, grumbling version of Christian in John Bunyan’s Calvinist classic, Pilgrim’s Progress. He must survive a series of tests (just as Christian managed to flee Doubting Castle), ideally to leave his faith stronger and more resilient.80 But part of the comfort of Bunyan’s allegory lies in its suggestion that doubt is an enemy of the self, a separate antagonist that makes doubt easier to quantify, vanquish, and elude. By contrast, Teufelsdröckh’s tests, having no simple answers, are more personal and existential. The hapless professor shambles from doubt to self-doubt, then on to doubt of others.

Teufelsdröckh tries to tune his faith and perspective to acceptance that “the whole world is … sold to Unbelief” (SR, 122). But although that prospect greatly saddens him, eventually he accepts that the passage between belief and unbelief is as inevitable as the pumping of the heart (his metaphor) “as in longdrawn Systole and longdrawn Diastole” (87). The metaphor is close to invoking Hutton’s and Lyell’s “longdrawn” arguments about the deposition and erosion of sand and shale over infinite time. There is reassurance, too, in likening the waxing and waning of faith to something far more comforting, such as the regularity of breathing. But Carlyle’s universe is largely secular; it is also troubled by a sense that God has abandoned it, leaving humanity very much to its own devices.

Teufelsdröckh takes a long time to accept that belief passes and returns, just as the seasons do. He fights the idea for years, his intellectual labor full of “long details on his ‘fever-paroxysms of Doubt.’” He also describes how, “in the silent night-watches, still darker in his heart than over sky and earth, he … cast himself before the All-seeing, and with audible prayers, cried vehemently for Light, for deliverance from Death and the Grave” (SR, 88).

Doubt isn’t the only object at which the professor is angry. If God turns out to exist after all, the professor fumes, how could he sit by, idle, while earthquakes and other natural disasters occur? The anger turns to bargaining, before it yields to something closer to secular acceptance. The plaintive question “Is there no God …?” leads Carlyle’s professor to ask what meaning “Duty” might have in a nonreligious context and whether belief in general is merely a “false earthly Fantasm” (SR, 121).

In Carlyle’s hands, doubt and belief are remarkably close to fear, an emotion we have traced in Lyell’s scientific notebooks. It is as if doubt prompts the poor, pitiable “Devil’s Dung” to wonder whether fear was really the element that held everything together in the first place. “Strangely enough,” he writes, “I lived in a continual, indefinite, pining Fear; tremulous, pusillanimous, apprehensive of I knew not what: it seemed as if all things in the Heavens above and the Earth beneath would hurt me; as if the Heavens and the Earth were but boundless jaws of a devouring monster, wherein I, palpitating, waited to be devoured” (SR, 125).

It is an extraordinary passage, full of revelation about the meaning of belief and the fear of giving it up. Indeed, it is only when the professor almost angrily confronts himself over the meaning of his fear that he is able to put it in some perspective: “What art thou afraid of? Wherefore, like a coward, dost thou forever pip and whimper, and go cowering and trembling? Despicable biped! what is the sum-total of the worst that lies before thee? Death? Well, Death; and say the pangs of Tophet too, and all that the Devil and Man may, will, or can do against thee!” (SR, 125).

“What art thou afraid of?” It is an excellent, and surely quite necessary question to ask in light of Lyell’s and Carlyle’s tangled intellectual and religious doubts. If the fear that Carlyle’s professor describes is merely imaginary, then nothing confronted head-on will look as ominous. The specter-mongering terror will collapse into a heap on the floor. But it didn’t quite do so for Carlyle himself, even years after his “tailor” had been “retailored.” And for others as well, such as John Henry Newman and Anne Brontë, the fears that sprang from doubting the existence of God remained real enough to be palpable.