Articles and Pronominal Adjectives

Gender and the Definite Article

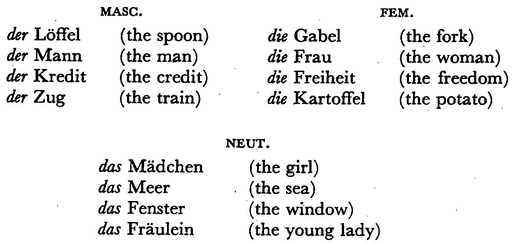

German nouns each belong to one of three genders: masculine, feminine, or neuter. This is purely a grammatical classification, and need not be related to the sex of the person or thing concerned. Inanimate or sexless objects and abstract ideas are classified as masculine, feminine, or neuter solely because of the pattern of the language.

There are no easy rules for determining the gender of a noun. However, in most instances, male persons will be masculine, and female persons will be feminine; but this is not always the case, as you can see from das Mädchen (neuter) above. All nouns that end in -chen or -lein, as for example, Mädchen and Fräulein, above, are neuter.

Do not try to learn many very complex rules for determining the gender of nouns. Instead, memorize the definite article with each noun.

The Word for “the”

(The Definite Article)

In English we have only a single form to express the definite article in all grammatical situations. We always say the. In German the definite article is more complex and changes accord. ing to the case, number, and gender of the noun it accompanies. The German definite article always “agrees” with the accompanying noun; that is, it takes the same case, gender, and number as that noun.1 The forms of the German definite article are given below:

Memorize these forms, for they are very important. Der-die-das is one of the most common words in German, and the endings it displays are also used to form independent adjectives and certain pronominal adjectives (see p. 27 and 35).

Observe that there are patterns in the declension of der-die-das:

1. The nominative and accusative forms of the feminine article are identical, as are the respective forms of the neuter article.

2. In the genitive and dative cases singular, the masculine and neuter forms are identical.

3. Feminine singular forms are the same in the genitive and dative.

4. All genders share the same forms in the plural.

5. Der functions for a masculine noun in the nominative case, but is also used for a feminine noun in the genitive and dative cases, and for the genitive plural of all nouns.

The Words for “a” and “an”

(The Indefinite Article)

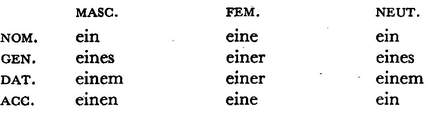

The German words ein-eine-ein, which correspond to “a” and “an” in English, agree in case and gender with the noun they accompany. Their forms are:

Observe that the declension of the masculine and neuter indefinite articles is identical, except for the accusative forms.

Naturally there are no plural forms for ein-eine-ein, just as there are none in English for “a” or “an.”2

Können Sie mir einen Arzt empfehlen?

[Can you to me a doctor recommend?]

Can you recommend a doctor to me?

The noun, (der) Arzt, in the above sentence, is masculine, and appears here in the accusative case because it is the direct object of the verb, empfehlen. It is therefore necessary to express the indefinite article in the masculine accusative form, einen.

Examples of the Definite Article

(Showing Agreement with Noun in Case, Gender, and Number)

The “der-words”

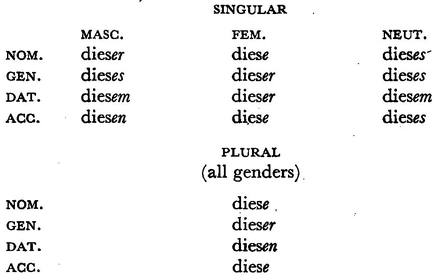

Certain pronominal adjectives take the same endings, when they are declined, as the definite article, der-die-das.3 Because of this similarity in declension, these words are called “der-words.” The most common are:

| dieser | this |

| jener | that |

| jeder | every |

| welcher | which |

We shall decline only one of these words in full; the others are all declined in the same manner.

Wieviel kostet dieses Zimmer?

[How much costs this room?]

How much does this room cost?

The pronominal adjective, dieses, in the above sentence, is nominative, neuter, singular, because the noun, Zimmer, to which it refers, is neuter and appears in the nominative case as the subject of the sentence.

Von welchem Bahnsteig fährt dieser Zug ab?

[From which platform travels this train off?]

From which platform does this train leave?

The word welchem is dative, masculine, singular because it must agree with Bahnsteig, a masculine noun which takes the dative case as the object of the preposition von. Dieser is nominative, singular, masculine since Zug, which it modifies, is a masculine noun here used in the nominative case as the subject of the sentence.

The “ein-words”

A group of pronominal adjectives are declined just like ein-eine-ein, and, like the indefinite article, agree in case, gender, and number with the noun they modify. The most common “ein-words” are:

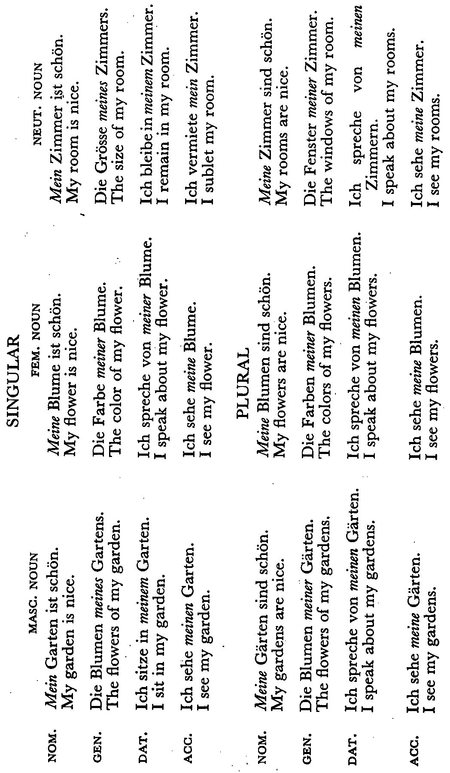

We shall decline only one of these words in full, as the others are all declined in the same manner.

Examples of “ein-words”

(Showing Agreement with Noun in Case, Gender, and Number)

Study this declension and the examples that follow; then refer back to the declension of the “der-words.” You will note many similarities. Only the singular forms differ from the der forms, and even here the differences are minor, although important for meaning. The endings for all plurals are, in fact, identical for the “der-words” and “ein-words.”

The Word “kein”

The word kein deserves special comment, since its use is often difficult for the student. Kein is a negative adjective, and corresponds to the English word no, when no is used to modify a noun.

Wir werden keine Zeit fur Museen haben.

[We shall no time for museums have.]

We shall have no time for museums.

Ich habe keine Briefe für Sie.

I have no letters for you.

In English we have two ways of making a sentence negative. We can use the idea of negation with nouns, as in the English sentences above, or we can express the same idea by associating the idea of negation with the verb, and using the adverb not: We shall not have time for museums. I do not have any letters for you. Both ways are grammatically correct, but we usually prefer the idea of verbal negation: We shall not have time, instead of we shall have no time.

The German adverb nicht corresponds to the English adverb not, and the adjective kein to the English modifier no. In use, however, German differs from English. When speaking German, you should use the kein form whenever possible because it is preferred usage. It is as if you transferred every English negative sentence to a “no” form. Thus, you should not say in literal translation:

Ich möchte heute nicht ein Frühstück.

[I want today not a breakfast.]

But you should say:

Ich möchte heute kein Frühstück.

[I want today no breakfast.]

I don’t want any breakfast today.

Or, instead of saying:

Wir haben noch nicht Billets gekauft.

[We have yet not tickets bought.]

We have not yet bought tickets.

Say:

Wir haben noch keine Billets gekauft.

[We have yet no tickets bought.]

We haven’t bought any tickets yet.