Adjectives and Adverbs

Adjective Endings

In English, adjectives are undeclined; our adjectives keep the same form in all situations, and do not take endings to show agreement in case, gender, and number with the noun they accompany. German adjectives are more complex because they can take many endings that differ according to the words they accompany. There are three separate series of endings for adjectives:

1. Endings used when an adjective is preceded by the definite article (der-die-das) or a “der-word.”

2. Endings used when an adjective is preceded by the indefinite article (ein-eine-ein) or an “ein-word.”

3. Endings used when an adjective is independent.

Adjectives with “der-words”

Refer to p. 24 where the declension of der-die-das is discussed, and to p. 27 where the declension of dieser (this), jener (that), jeder (every), and welcher (which) is discussed. You will recall that these four words are called “der-words” because they take the same endings as the German word for the.

When adjectives are preceded by the definite article (der-die-das) or by a “der-word,” they are declined as follows:

| SINGULAR | ||

|---|---|---|

| MASC. NOUN | FEM. NOUN | |

| (the English garden) | (the English city) | |

| NOM. | der englische Garten. | die englische Stadt. |

| GEN. | des englischen Gartens. | der englischen Stadt. |

| DAT. | dem englischen Garten. | der englischen Stadt. |

| ACC. | den englischen Garten. | die englische Stadt. |

| NEUT. NOUN (SING.) | ||

| (the English book) | ||

| NOM. | das englische Buch. | |

| GEN. | des englischen Buches. | |

| DAT. | dem englischen Buch. | |

| ACC. | das englische Buch. | |

| PLURAL | ||

| MASC. NOUN | FEM. NOUN | |

| (the English gardens) | (the English cities) | |

| NOM. | die englischen Gärten. | die englischen Stadte. |

| GEN. | der englischen Gärten. | der englischen Städte. |

| DAT. | den englischen Gärten. | den englischen Städten. |

| ACC. | die englischen Garten. | die englischen Stadte. |

| NEUT. NOUN | ||

| (the English books) | ||

| NOM. | die englischen Bücher. | |

| GEN. | der englischen Bücher. | |

| DAT. | den englischen Büchern. | |

| ACC. | die englischen Bücher. | |

As you will observe, the only forms which do not take -en as an ending are the three nominative singular forms and the feminine and neuter accusative singular forms. This set of endings is then simple to memorize: the ending is -en throughout, except in the nominative singular and the feminine and neuter accusative singular where it is -e.

Ich würde gern den deutschen Film sehen.

[I would gladly the German film see.]

I would like to see the German film.

Wo ist der nächste Flugplatz?

Where is the nearest airfield?

Diese süsse Marmelade schmeckt mir nicht.

[This sweet marmalade pleases me not.]

I don’t like this sweet marmalade.

Adjectives with “ein-words”

Refer to p. 25 where the forms are given for the declension of ein-eine-ein (a, an), and to p. 28 where the declension of mein (my), sein (his, its), ihr (her), kein (no, not any), unser (our), ihr (their), and Ihr (your) is discussed. You will recall that these words are called “ein-words” because they take the same endings in the singular as ein.

Adjectives that are preceded by the indefinite article or any form of any of the “ein-words” take the following endings:

| SINGULAR | ||

| MASC. | FEM. | |

| (a good cheese) | (a good trip) | |

| NOM. | ein guter Käse | eine gute Reise. |

| GEN. | eines guten Käses. | einer guten Reise. |

| DAT. | einem guten Käse. | einer guten Reise. |

| ACC. | einen guten Käse. | eine gute Reise. |

| NEUT. | ||

| (a good book) | ||

| NOM. | ein gutes Buch. | |

| GEN. | eines guten Buches. | |

| DAT. | einem guten Buch. | |

| ACC. | ein gutes Buch. | |

| PLURAL | ||

| MASC. | FEM. | |

| (my good cheeses) | (my good trips) | |

| NOM. | meine guten Käse. | meine guten Reisen. |

| GEN. | meiner guten Käse. | meiner guten Reisen. |

| DAT. | meinen guten Käsen. | meinen guten Reisen. |

| ACC. | meine guten Käse. | meine guten Reisen. |

| NEUT. | ||

| (my good books) | ||

| NOM. | meine guten Bücher. | |

| GEN. | meiner guten Bücher. | |

| DAT. | meinen guten Büchern. | |

| ACC. | meine guten Bücher. | |

As you will notice, the only adjective forms that do not take -en are the same ones that do not take -en when the adjective is preceded by a “der-word” (pp. 32–33): all forms of the nominative singular, and the feminine and neuter accusative singular. As a further memory aid, note that the feminine nominative and accusative forms are identical, and that the neuter nominative and accusative forms are also alike.

Hier ist meine neue Fahrkarte.

Here is my new ticket (for a train).

Das ist ein offener Wagen.

That is an open car.

Können Sie ein englisches Rezept füllen?

[Can you an English prescription fill?]

Can you fill an English prescription?

Ich will kein billiges Opernglas kaufen.

[I want no cheap opera glass to buy.]

I do not want to buy a cheap opera glass.

In the first example, neue is feminine, nominative, singular because die Fahrkarte, a feminine noun, is used in the nominative case as a predicate noun.

In the second example, offener is masculine, nominative, singular because der Wagen, a masculine noun, is also the predicate noun.

Englisches in the third sentence, and billiges in the fourth, both end in -es because they are neuter, accusative, singular. Das Rezept and das Opernglas are both used as direct objects which require the accusative case.

Independent Adjectives

An adjective which is not preceded by any of the “der-words” or “ein-words,” or by either the definite or indefinite article, takes the following endings:

| SINGULAR | |||

| MASC. NOUN | FEM. NOUN | NEUT. NOUN | |

| (black coffee) | (warm milk) | (bad weather) | |

| NOM. | schwarzer Kaffee | warme Milch | schlechtes Wetter |

| GEN. | schwarzen Kaffees | warmer Milch | schlechten Wetters |

| DAT. | schwarzem Kaffee | warmer Milch | schlechtem Wetter |

| ACC. | schwarzen Kaffee | warme Milch | schlechtes Wetter |

| PLURAL | |||

| (all genders) | |||

| (green apples) | |||

| NOM. grüne Äpfel | |||

| GEN. grüner Äpfel | |||

| DAT. grünen Äpfeln | |||

| ACC. grüne Äpfel | |||

These endings are known as strong endings. They are the same as those used on the “der-words” themselves, except in the masculine and neuter genitive singular where the ending is -en instead of -s.

Haben Sie frisches Brot?

Do you have fresh bread?

Möblierte Wohnungen sind nicht leicht zu finden.

Furnished apartments are not easy to find.

Das sind ausländische Poststempel.

Those are foreign postmarks.

Predicate Adjectives

When adjectives are used as predicate adjectives, that is, when they are used after a verb of being to express something about the subject of the sentence, they do not take endings, but are used in their basic form. Remember this rule of thumb: whenever the adjective follows the noun it modifies it is invariable, i.e., never declined.

Dieses Brot ist nicht frisch.

This bread is not fresh.

Ist dieses Haus möbliert?

Is this house furnished?

Dieser Käse bleibt lange frisch.

[This cheese stays long fresh.]

This cheese stays fresh for a long time.

Comparison of Adjectives

German adjectives form the comparative and superlative forms in much the same way as do English adjectives. In most instances, the comparative is formed by adding -er to the basic German adjective (or simply -r if the adjective already ends in -e), and the superlative is formed by adding -st or -est to the adjective. The -est ending is added to adjectives which end in d, t, s, or z, to make the ending fully audible. You never use the German equivalent of more. or most as is often done in English.

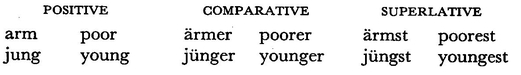

As you will observe, the adjective alt takes an umlaut in its comparative and superlative forms. Many other common one-syllable adjectives also umlaut if their stem vowel permits an umlaut. (See p. 93 for discussion of the umlaut.) Examples of such adjectives are:

Many other one-syllable adjectives, on the other hand, do not take an umlaut. There is no general rule. Either memorize the comparative form of the adjective or else consult your dictionary.

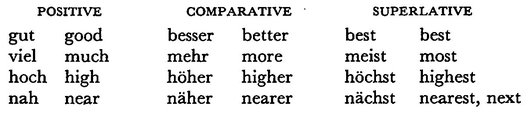

As in English, certain adjectives form their comparatives and superlatives irregularly:

Using the Comparative and Superlative of Adjectives

Comparatives and superlatives of adjectives are treated just like other adjectives, and take endings according to the same rules. (See pp. 32, 34, and 35 for full rules and examples.)

Reifere Birnen sind besser.

Riper pears are better.

Der teuerste Hut kostet fünf Mark.4

The most expensive hat costs five marks.

Mein ältester Sohn konnte nicht mitkommen.

My oldest son could not come along.

In the first sentence, reifer is an independent adjective, hence takes -e in the nominative plural. Besser is a predicate adjective, i.e., it follows the noun it modifies, hence takes no ending.

Teuerste, in the second sentence, is preceded by the definite article, der, hence takes -e for its masculine, singular, nominative form.

Ältester, in the third sentence, is used after a masculine singular “ein-word,” hence takes -er.

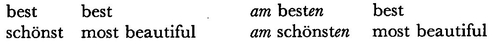

There is one situation in the use of the superlative, however, which is highly idiomatic, and has no counterpart in English. It concerns the manner of expressing a superlative quality idea. There are two ways of expressing this in German:

1. When you use a superlative adjective with a noun, you use the forms we have been discussing up to now, and you treat the superlative exactly like any other adjective.

Die Donau ist der schönste Fluss in Österreich.

The Danube is the most beautiful river in Austria.

2. When you use the superlative adjective as a predicate adjective with the verb sein (to be), bleiben (to stay or remain), werden (to become), or scheinen (to appear or seem)—without a noun, or as an adverb—you must use a different form. Add -n or -en to the ordinary superlative form, and put the word am in front of it:

Die Donau ist am schönsten in Osterreich.

The Danube is most beautiful in Austria.

Der Rhein fliesst am schnellsten in der Schweiz.

The Rhine flows fastest in Switzerland.

Making Comparisons

Comparisons are made in much the same way as they are made in English. The English construction as . . . as is translated by so . . . wie.

Dieser Mann ist so alt wie mein Bruder.

This man is as old as my brother.

Than, when used with a comparative adjective, is translated by als.

Dieser Mann ist alter als mein Bruder.

This man is older than my brother.

Adverbs

Adverbs, as in English, do not take declensional endings; they keep the same form no matter how they are used in the sentence.

Certain words are always adverbs:

You will find these and others in any dictionary.

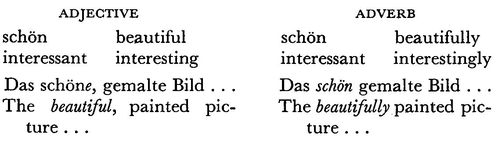

Other adverbs, however, are formed from adjectives. Their ordinary or positive form is the same as the adjective itself, but completely without declensional ending:

In the first sentence, schöne is an adjective, and has the suitable ending for an adjective following the definite article. In the second sentence, schön is an adverb, and therefore takes no ending.

The comparative of adverbs is the same as the comparative of the corresponding adjectives, but again no declensional endings are used:

Diese Eier sind heute besser gebraten.

[These eggs are today better fried.]

These eggs are fried better today.

In the superlative, however, only the am . . . -sten form (discussed on p. 39) is used:

| am schönsten | most beautifully |

| am interessantesten | most interestingly |

| am feinsten | most finely |

Certain adverbs have irregular comparatives and superlatives:.

| bald, eher, am ehesten | soon, sooner (rather), soonest |

| viel, mehr, am meisten | very (much), more, most |

| gern, lieber, am liebsten | willingly, more willingly, most willingly |

Gern lends itself to an idiomatic construction which is discussed below.

The Word “gern”

Gern is a much-used word in German, and can best be translated as gladly or willingly or as a form of the verb to like.

| Wir reisen gern. | Ich tue es gern. |

| We like to travel. | I’ll gladly do it. |

Gern haben is an idiom and means to like:

| Ich habe Sauerkraut gern. | Wir haben Mathematik gern. |

| I like sauerkraut. | We like mathematics. |