Simple Verbs

The Present Tense

Although we are usually not aware of it, in English we have three different ways of forming a present tense. We can say I walk, or (progressive) I am walking, or (emphatic) I do walk. There are slight shades of meaning which distinguish these forms. In German, however, there is only one way of expressing present time and only one set of forms to convey all the meanings of the three English forms:

Ich fahre mit dem Zug nach Berlin.

[I travel with the train to Berlin.]

I go (am going) (do go) to Berlin by train.

The word fahre, as you have probably observed, means, according to context, I go, I am going, or I do go.

Forming the Present Tense in German

In most cases the present tense of German verbs is formed according to simple and regular rules. As a starting point take the infinitive of the verb, just as you do in English:

This form is used as a basis for all forms of the present. As you notice, it ends in -en, or less commonly, in -n. The present tense is then made as follows:

1. All the plural forms, including Sie (you, even if referring to only one person) are exactly the same as the infinitive. This is true of every verb in the German language, with only one exception: sein (to be). We shall discuss sein separately, since it is very irregular (see p. 52).

2. All the I forms (first person singular) drop the -en or -n of the infinitive, and add -e. This rule is true of almost all verbs, although there is a very frequently used group of verbs like can, must, may, etc. which are irregular and which we shall discuss separately (p. 67).

3. All the he-she-it forms (third person singular) drop the -en or -n of the infinitive, and add -t. This rule has exceptions:

(a) the words for can, may, shall, must, will, is, has, etc., which we shall consider separately.

(b) A very important group of verbs which make this change, but also change the vowel in their stem. These are called stem-changing verbs, and shall be described immediately.

(c) In verbs whose stem ends in d or t, a connective-e-is inserted between stem and ending. Note redet above.

Forming the Present Tense of Stem-changing Verbs

Some verbs, besides adding -t to their stem to form the he-she-it forms of the present tense, also change the vowel in the stem. In such cases an a in the stem is changed to ä, and e is changed to either i or ie, depending upon the individual verb. Three common verbs of this sort are:

| e TO i | |

|---|---|

| geben | to give |

| ich gebe | I give |

| er gibt | he gives |

| sie gibt | she gives |

| es gibt* | it gives |

Note: There are no stem changes in the plural.

There is no way to identify such stem-changing verbs beyond the fact that they are all strong verbs (see p. 54 for a definition of a strong verb). You must either memorize them or consult a dictionary when you are in doubt. Most dictionaries and grammars indicate these verbs either by quoting such forms in full, or by some such notation as sehen (ie), plus the vowel changes in the past tense and in the past participle.

The Verbs “to be” and “to have”

The verbs sein (to be) and haben (to have) are as commonly used in German as their counterparts are in English. Besides their use as words by themselves, they are also used to form other verb forms, in much the same manner as they are in English. (See pp. 56 and 58 for their use as auxiliary verbs.)

It will prove a great help to you if you practice these forms until they become as automatic as their English equivalents.

Observe that you have to memorize only two or three forms for each tense of these two verbs. Also notice how close these forms resemble their corresponding English forms.

Wo ist die Wäscherei?

Where is the laundry?

Ich habe einen internationalen Führerschein.

I have an international driver’s licence.

Haben Sie ein Zimmer frei?

[Have you a room vacant?]

Do you have a vacant room?

The Past Participle

One of the basic forms of the German verb which you must learn is the past participle. It is sometimes used as an adjective, as in English, but its most frequent use is to form the perfect tenses, as in English. In the English sentence “I have not eaten since breakfast,” eaten is a past participle.

In English, as you will notice, if you run mentally through a few verbs, there are two ways of forming the past participle. Some verbs, like learn, walk, live, fear, and laugh form their past participle by adding -d or -ed to the basic form: learned, walked, lived, feared, laughed. These are called weak verbs.

Other verbs, however, form their past participles in a more complex way. Take the English verbs find, sing, swim, speak, and drink. They form their past participles respectively as found, sung, swum, spoken, and drunk. The points that they have in common are (1) they do not add -d or -ed to form their past participle, and (2) they change the vowel in their stem. These are called strong verbs.

In German exactly the same situation exists. There are strong verbs and there are weak verbs. And, as in English, there are a few irregular verbs.

How to Tell a Strong Verb from a Weak Verb

Unfortunately, there is no simple rule to aid you in identifying strong or weak verbs. However, comparable verbs in English frequently furnish valuable information for you.

For example, if there is an English verb which is closely related to the German verb—as live is to leben, see is to sehen, drink is to trinken, find is to finden—in most cases the German verb will be strong if the English cognate is strong. This is, however, not always the case, and it is safer (1) to memorize the past participle of a verb when you learn the verb, and (2) to get into the habit of looking up unfamiliar forms in your dictionary.

Forming the Past Participle of Weak Verbs

German weak verbs form their past participles very simply. They add -t (or -et if the stem ends in d or t) and they add ge- to the front of the verb stem. (Those exceptional verbs which do not add ge- are discussed on pp. 55—56.)

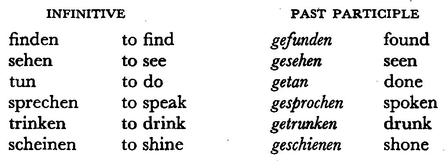

Forming the Past Participle of Strong Verbs

German strong verbs, like English verbs, are more difficult to analyze. They

- retain the original ending of the infinitive (-n or -en)

- prefix ge-

- usually change the vowel in the stem of the verb.

There are no simple rules for determining what sound changes are made in the vowels of German past participles, just as there are no simple rules in English. Memorize the past participle forms or else look them up in a dictionary.

There are also a few frequently used verbs (strong or weak) which, like their English counterparts, form irregular past participles:

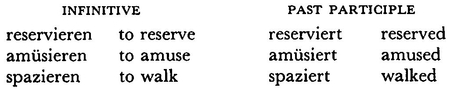

Some Exceptions

A group of irregular weak verbs borrowed from the Romance languages do not prefix a ge- to the verb stem to form the past participle, but do add a final -t. The infinitives of these verbs all end in -ieren. Examples:

Important Note: All the rules and procedures which we have discussed in this section apply only to simple verbs. Separable verbs and inseparable verbs (for which see respectively pp. 75 and 79) form their past participles in a slightly different manner. For ease of learning, however, review the rules for forming the past participles of simple verbs first. Later, when you study separable and inseparable verbs, you will see that forming their past participles involves only slight modification of these rules.

The Conversational Past Tense

The most frequently used past tense in German is the conversational past, which corresponds in formation to the English present perfect tense. As in English, it is formed with the past participle and an auxiliary verb.

Er hat hier ein Zimmer für uns reserviert.

[He has here a room for us reserved.]

He reserved (or has reserved) a room for us here.

In English, has reserved is present perfect tense, and hat reserviert in German is conversational past or present perfect tense. Observe that hat reserviert does not have to be translated as has reserved; it can mean simply reserved.

In modern English we form all present perfect tenses by using forms of the verb to have and the past participle of a verb. Most German verbs follow the same pattern, using forms of the verb haben (to have) and a past participle:

| ich habe gesehen | I saw; I have seen |

| er, sie, es hat gefunden | he, she, it found; he, she, it has found |

| wir haben gesagt | we said; we have said |

| sie, Sie haben gekauft | they, you bought; they, you have bought |

Der Kellner hat einen guten Wein gebracht.

[The waiter has a good wine brought.]

The waiter brought a good wine.

Danke, ich habe genug gesehen.

[Thank you, I have enough seen.]

Thank you, I have seen enough.

Observe that the past participle is placed at the end of these sentences, and that German follows a characteristic word order in sentences that contain perfect forms. You will find this important point explained in detail on p. 85.

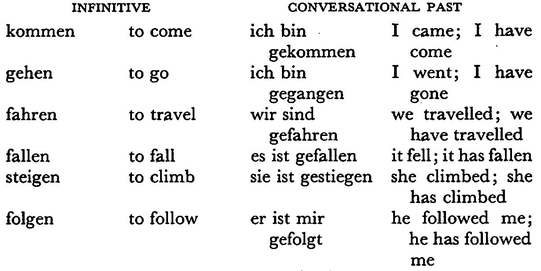

Most German verbs make their conversational past tense by using haben as their auxiliary or working verb. Some verbs, however, do not use haben, but use, instead, forms of sein (to be).

| ich bin gegangen | I went; I have gone |

| sie, er, es ist gestorben | she, he, it died; she, he, it has died |

| wir sind geblieben | we remained; we have remained |

| sie, Sie sind gefallen | they, you fell; they, you have fallen |

Die Teller sind kalt gewesen.

[The plates are cold been.]

The plates were cold.

Meine Frau und Tochter sind allein ausgegangen.

[My wife and daughter are alone out-gone.]

My wife and daughter went out alone.

This may seem to be a strange usage, but actually English made use of forms exactly like these until only a few centuries ago. The King James Bible, for example, uses such forms as I am come, Christ is risen, Babylon the Great is fallen.

“Haben” and “sein” as Auxiliary Verbs

Any German verb which takes a direct object must use haben to form its conversational past and other perfect tenses. This includes ordinary transitive verbs, reflexive verbs, and most impersonal verbs. Most intransitive verbs and most modal verbs also use haben to form perfect tenses.

Only three categories of German verbs use sein as an auxiliary. These are:

1. Verbs involving a change of position that cannot take an object.

2. Verbs involving a change of condition that cannot take an object.

3. Miscellaneous verbs

If you find it difficult to remember these categories, memorize a complete perfect form when you learn a verb, or else consult the dictionary. Most dictionaries will show “aux. h.” for haben or “aux. s.” for sein to indicate the proper auxiliary.

How to Form the Simple Past Tense

You have already learned the conversational past tense, which corresponds in form to the English perfect or present perfect tense. You should also learn the German simple past tense, which corresponds in form to the English simple past.

German verbs, like English verbs, fall into two large categories: weak verbs and strong verbs. Weak verbs in both languages do not change their stem vowel in forming their simple past tense. Strong verbs in both languages do change their stem vowels. (See pp. 53—54 for discussion of strong and weak verbs.)

German weak verbs form their simple past by adding the letter -t to the stem of the verb, plus the ending -e in the singular, and -en in the plural. English corresponding forms are live, lived; walk, walked; grasp, grasped, etc.

Observe that a connective -e- has been added between the stem and the endings of the verb antworten. This is done with verbs whose stem ends in -d or -t, to make the past tense audibly distinct.

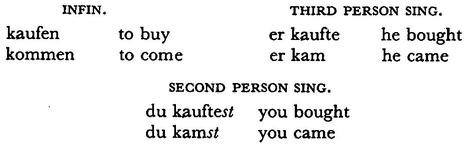

German strong verbs form their simple past tense by changing their stem vowel; no ending is added to the singular forms, while -en is used for the plural forms. You are familiar with similar vowel changes in English strong verbs: swim, swam; give, gave; take, took; strive, strove; see, saw, etc.

See p. 97 for a list of the more common strong verbs.

How to Use the Simple Past Tense

On the whole, the simple past tense and the conversational past in German are interchangeable:

Was haben Sie gesagt? (conversational past)

What have you said? What did you say?

Was sagten Sie? (simple past)

[What said you?]

What did you say? What have you said?

Where English uses a past progressive tense (see p. 108), however, you should use the simple past tense in German.

Als wir Kaffee tranken, gaben wir dem Kellner ein Trinkgeld.

[When we coffee were drinking, gave we to the waiter a tip.]

When we were drinking coffee, we gave the waiter a tip.

Commands

Commands are normally expressed by taking the Sie form of the present tense of the verb, and placing the verb before the pronoun Sie.

Kommen Sie herein und schliessen Sie die Tür!

[Come you in and shut you the door!]

Come in and shut the door!

Observe that the pronoun Sie is repeated if two or more commands are given in the same sentence.

Negative commands are made in the same way as positive commands, with the appropriate negative adverbs and adjectives. German does not have a construction exactly parallel to the English Do not ...

Bestellen Sie bitte heute keinen Kaffee!

[Order you please today no coffee!]

Please don’t order coffee today!

The usual word for please, bitte, does not change, any more than does its English equivalent.

Observe that word order for commands is like that for questions. In conversation, however, a question is spoken with a rising inflection of the voice, as in English.

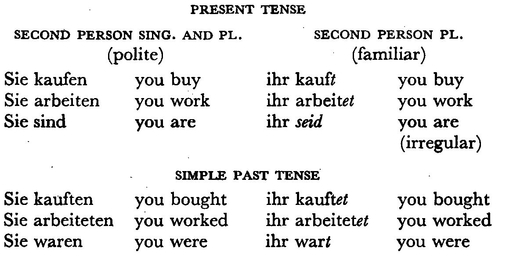

Verbs with “du” and “ihr”

As has been explained on p. 43, there is another way of saying you besides the polite form, Sie. This is the familiar personal pronoun: du, singular; ihr, plural. We do not advise you to use these forms until you know the situations that call for them, but we include them so that you will recognize them. As a general rule, du takes a verb form that is closely related to the Old English thou form—thou seest, thou doest, etc. In present tenses, the du form is made by dropping the t of the he-she-it form, and adding, instead, -st. As this implies, if the verb is a stem-changing verb, the du form uses the changed vowel.

In the simple past, you add -st to the he-she-it form:

The plural of du is ihr, which should not be confused with ihr the dative form of sie (she). Its verb form is made by taking the third person plural of the verb concerned, dropping the -n (or -en) and adding -(e)t. As you can see, it is often identical with the third person singular.

To form the past tense, add -et to the past stem of all weak and strong verbs whose stem ends in -d or -t; add -t to all others.

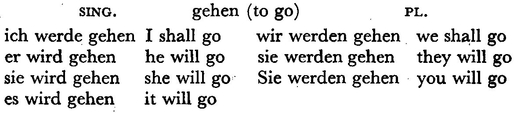

How to Form the Future Tense

The future tense in German is made by using the present tense of the verb werden with the infinitive of the verb concerned in the sentence. The German future corresponds, as you can see, almost exactly with the English use of shall and will (plus an infinitive) to form the future. Note that werden is an irregular verb.

Ich werde heute nach Hause zurückkommen.

[I shall today to home back-come.]

I shall return home today.

Werden Sie einen Platz für mich auf dem Flugzeug reservieren?

[Will you a place for me on the airplane reserve?]

Will you reserve a place for me on the airplane?

Observe that in these independent sentences in the future tense, the infinitive is placed at the very end (see p. 85).

You can often avoid using the future tense by using the present tense with an indication of time.

Ich gehe heute abend ins Theater.

[I am going today evening into the theatre.]

I am going to the theatre tonight.

As you have probably observed, this corresponds to English usage, i.e., the present tense is used to indicate a future action with the help of tonight.

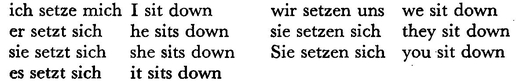

Reflexive Verbs and Reflexive Pronouns

Reflexive verbs in German use the following pronouns, which correspond in general to the English pronouns ending in -self:

| mich or mir7 | myself |

| sich | himself, herself, itself, oneself, yourself, themselves, yourselves |

| uns | ourselves |

These pronouns are called reflexive pronouns, and the verbs that use them are called reflexive verbs. In English we use such reflexive verbs occasionally (I washed myself. He locked himself out. We found ourselves late, etc.), but German uses them more often, and in situations where we do not use them. They are indicated in dictionaries by such abbreviations as refl. or rf. or by the presence of the pronoun with the infinitive: sich freuen (to rejoice).

Reflexive verbs are conjugated like other verbs, and all use haben in forming their conversational past tense. The reflexive pronoun is placed in the sentence exactly as if it were an object pronoun (which in a way it is).

sich setzen (to sit down)

Können Sie sich nicht an ihn erinnern?

[Can you yourself not about him remember?]

Can’t you remember him?

Ich habe mich geirrt, aber ich will mich bessern.

[I have myself erred, but I want-to myself improve.]

I have made a mistake, but I want to improve.

As we observed in the first paragraph of this section, two forms are given for myself: mich and mir. Mich is the form ordinarily used, but in certain verbs where the word myself conveys the idea to myself or for myself, mir is used. You should memorize these important verbs that take mir:

| sich denken | to imagine |

| sich Sorge machen um etwas | to worry about something |

| sich weh tun | to hurt oneself |

| Ich denke es mir. | |

| I imagine it. | |

| Ich mache mir Sorgen um etwas. | |

| I worry about something. | |

| Ich tue mir weh. | |

| I hurt myself. | |

| Observe the use of mir in the following examples: | |

| Ich kaufe mir ein Buch. | |

| I buy myself a book | |

| Ich lasse mir das Haar schneiden. | |

| [I have myself the hair cut.] | |

| I have my hair cut. | |

Note 1. Observe that sich, the reflexive pronoun meaning yourself or yourselves is not capitalized, even though Sie is.

Note 2. Do not confuse the -self pronouns used with reflexive verbs with such expressions as I, myself; you, yourself, etc. These use a different form, selbst, which does riot change.

Sie haben es selbst gesagt.

[You have it yourself said.]

You yourself said it.

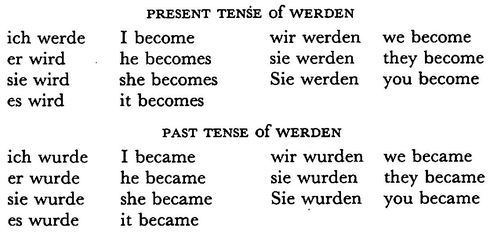

Forming the Passive Voice

The same auxiliary verb which was used to form the future tense (see p. 63) is also used to form the passive voice in German. This is the verb werden (to become). The present passive is formed by using the present tense of werden with the past participle of the verb concerned, and the past passive is formed by using the past tense of werden with the past participle of the verb.

Examples of passive voice:

Meine Uhr wird von ihm gereinigt.

[My watch becomes by him cleaned.]

My watch is being cleaned by him.

Das Buch wurde von meiner Frau gekauft.

[The book became by my wife bought.]

The book was bought by my wife.

Observe that the past participle has been placed at the end of these two sentences, just as in the perfect tenses. It follows the same rules for placement (see p. 85). Also notice that by in passive sentences is usually translated by von, less often by durch.

How to Avoid the Passive Voice

The German passive voice is often considered difficult by Americans, and, indeed, in perfect tenses it can be complex. Actually, as in English, there are very few ideas that demand a passive sentence; most concepts can be expressed just as well by re-wording your thought to an active form. The two sentences in the preceding section, for example, could just as well be expressed as “He is cleaning my watch” and “My wife bought this book.”

Another way to avoid the passive voice is to use the pronoun man to express the same idea. Man is an impersonal pronoun which is used when no specific reference is intended; it corresponds to the impersonal you or impersonal they or one in comparable English sentences: you may smoke in the lobby, they say it will be a cold winter, one does not often hear such fine playing. Thus, the passive voice in the sentence

Diese Strasse wurde letztes Jahr gebaut.

[This street was last year built.]

This street was built last year.

can be avoided by saying:

Man hat diese Strasse letztes Jahr gebaut.

[One has this street last year built.]

They built this street last year.

Expressing “Must,” “Can” and “Want to”

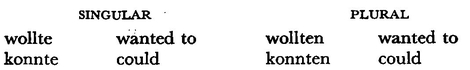

The German words which correspond to the English must, can, and want to are irregular in many of. their forms. Since they are just as common in German as in English, they should be memorized.

This is their present tense:

müssen (expressing the idea must, have to, etc.)

Observe that in all three of these verbs, all the singular forms are the same, for each verb, and all the plural forms are the same. You have to memorize only two forms for the present tense of each verb.

These three verbs take the infinitive of the complementary verb, exactly as their counterparts do in English. Observe that the infinitive is placed at the end of the clause (see p. 85 for the general rule).

Ich will meine Wäsche trocknen.

[I want-to my wash dry.]

I want to dry my wash.

Wir können die Musik nicht hören.

[We can the music not hear.]

We cannot hear the music.

Er muss sich jetzt ausruhen.

[He must himself now rest.]

He must rest now.

Observe that the word zu is not used with these verbs. They are followed directly by the infinitive, without zu. This corresponds to English usage with the comparable words can, could, should, would, must, etc.

The past tense of these verbs is formed in the following manner:

müssen (must, have to, etc.)

Wollen (to wish to) and können (to be able to) follow the same pattern of having all singular forms identical and all plural forms identical:

Herr Schmidt. konnte die Post nicht finden.

[Mr. Schmidt could the post office not find.]

Mr. Schmidt could not find the post office.

Wir mussten ihm den Schlüssel geben.

[We had-to to him the key give.]

We had to give him the key.

Sie wollten ihn nicht treffen.

[They wanted-to him not meet.]

They did not want to meet him.

The future of these three verbs, müssen, können, and wollen, is entirely regular, and is formed with werden, just as is the future tense of all other verbs. (See p. 63 for a full statement about the future of all verbs.)

Ich werde nicht kommen können.

[I shall not to come to be able.]

I shall not be able to come.

As you have probably noticed, there are two infinitives in the sentence, kommen and können. In such cases können or müssen or wollen is placed immediately after the other infinitive, as in the above example.

Would and Should

In English there are many situations where we use the words should or would with an infinitive. These situations indicate hope, belief, desire, indirect questions, indirect statements, and conditions. (See the examples below.) In most cases it is possible to translate these sentences into German, almost word for word, by using the words würde or würden with an infinitive: würde is used for singular forms; würden for plural forms.

| ich würde gehen | I would go |

| er würde kommen | he would come |

| sie würde sehen | she would see |

| es würde geschehen | it would happen |

| wir würden schreiben | we would write |

| sie würden lesen | they would read |

| Sie würden bezahlen | you would pay |

Ich hatte gehofft, Sie würden mir ein Zimmer reservieren.

[I had hoped, you would for me a room reserve.]

I had hoped you would reserve a room for me.

Meine Frau wünscht, Frau Schmidt würde bald schreiben.

[My wife wishes, Mrs. Schmidt would soon write.]

My wife wishes Mrs. Schmidt would write soon.

Ich würde das nicht sagen.

[I would that not to say.]

I wouldn’t say so.

Der Arzt sagte, er würde uns telefonieren.

[The doctor said, he would us telephone.]

The doctor said he would telephone us.

Wenn es billiger ware, so würde ich es kaufen.

[If it cheaper were, so would I it buy.]

If it were cheaper, I would buy it.

Wir haben nicht geglaubt, dass Sie uns verstehen würden.

[We have not believed, that you us understand would.]

We didn’t believe that you would understand us.

Die alte Dame fragte, ob es regnen würde.

[The old lady asked, whether it rain would.]

The old lady asked whether it would rain.

Observe the word order in the sentences, particularly that of the infinitives. The infinitives reservieren, schreiben, sagen, telefonieren, and kaufen are all at the end of their statements because they are in independent clauses (see p. 85). The infinitives verstehen and regnen, however, are in dependent clauses, and for this reason come before the working verbs würden and würde.

It must be noted that the word should is sometimes used in English with the pronouns I and we to express the same ideas as would in the above examples. Colloquially, we say, “If it were cheaper, I would buy it,” but in writing we might also say, “If it were cheaper, I should buy it.” Should, in these cases, does not mean ought to or must. When should means ought to or must, it is expressed differently in German. Singular forms use sollte with the infinitive; plural forms use sollten with the infinitive.

Er sollte nicht so spat auf bleiben.

[He should so late not stay-up.]

He should not stay up so late. He ought not to stay up so late.

Sie sollten sich Ihr Geld sparen.

[You ought yourself your money save.]

You ought to save your money.

Würde and würden are what is technically known as forms of the imperfect subjunctive of werden (to become), the same verb that you have used to form the future and the passive. By using würde and würden as indicated above, you will be able to express most of the ideas normally conveyed by the rather complex subjunctive forms for other verbs.

Impersonal Verbs

German, like English, has many impersonal verbs. Some of them correspond rather closely to English:

| es schneit | it snows, it is snowing |

| es regnet | it rains, it is raining |

| es geschieht | it happens, it is happening |

Impersonal verbs are used more commonly in German, however, and there are many German impersonal constructions that do not have English counterparts. Some of the most common of these German impersonal constructions are:

Es tut mir leid.

[It does to me sorrow.]

I am sorry.

Es gelingt ihm,seinen Freund zu erreichen.

[It succeeds to him his friend to reach.]

He succeeds in contacting his friend.

Es gefällt mir.

It pleases me.

Es fehlt mir die Zeit dazu.

[It lacks to me the time to this.]

I don’t have time for that.

Wie geht es Ihnen? Es geht mir gut.

[How goes it to you? It goes to me good.]

How are you? Good.

Es sind drei Manner im ersten Abteil.

There are three men in the first compartment.

Es fällt mir schwer.

[It falls me heavy.]

It is hard for me. I find it hard.

Es geht mir schlecht.

[It goes to me bad.]

Things are not well with me.

Es ist mir übel.

[It is to me sick.]

I feel sick. I feel nauseated.

Verbs that Take Their Objects in the Dative Case

Most German verbs use the accusative for their direct objects (see p. 96). There are a few very common verbs, however, which do not use the accusative, but the dative.

| antworten (to answer) | gehören (to belong to) |

| Antworten Sie ihm! | Der Koffer gehört meiner Frau. |

| Answer him! | The suitcase belongs to my wife. |

| danken (to thank) | glauben (to believe) |

| Wir haben ihm gedankt. | Ich glaube ihr. |

| We thanked him. | I believe her. |

| folgen (to follow) | helfen (to help) |

| Wir folgen dem Reiseführer. | Helfen Sie mir! |

| We follow the travel guide. | Help me! |

| gefallen (to please, to like) | |

| Diese Stadt gefallt mir. | |

| [This town pleases me.] | |

| I like this town. |